Railroad mergers haven’t happened in a while, and that’s a good thing. During the Reagan era, the country witnessed a rapid consolidation of its railroad industry. In the two decades following the 1980 Staggers Rail Act, the number of Class 1 freight railroads in the country fell from 39 to seven. The new millennium saw an industry dominated by four major railways that collectively controlled around 90 percent of the total domestic rail operating revenues.

In light of this rapid consolidation, regulators feared an eventual transcontinental rail duopoly. The Surface Transportation Board (STB) stymied railroad mergers in 2000, and issued new merger guidelines the following year, requiring that future deals would have to “enhance” competition. With the exception of Canadian Pacific-Kansas City Southern (CPKC), blessed with a waiver to be considered under the old merger guidelines, no Class 1 mergers have happened since the 2001 STB merger guidelines were released. That merger hiatus is set to be interrupted: In July, Union Pacific (UP) announced its intention to acquire Norfolk Southern (Norfolk) in an $85 billion deal.

The Economist touted the benefits of a UP-Norfolk tie-up, suggesting that the merger could lead to the “big four” railways becoming a “bigger two” railways. The magazine noted that UP-Norfolk merger would all but guarantee that BNSF and CSX combine as well. This potential rail duopoly presents a series of issues. Moving an already consolidated industry towards a duopoly means that shippers seeking to send traffic on overlapping routes will have fewer choices and will likely face higher prices. And railroad workers will have fewer employment options within an industry dominated by a duopoly. The STB will have to weigh the promised efficiencies against the harms to workers and shippers when considering this merger application.

Faster Speeds Are Not a Merger-Based Efficiency

Proponents of the UP-Norfolk merger argue that the arrangement will lead to faster trains, fewer delays, and better reliability. One purported benefit is that trains won’t need to interchange if they travel with the same railroad company along their entire route.

Here is The Economist’s merger-efficiency rationale, presumably helpfully shared by an industry lobbyist:

Avoiding interchanges between networks would mean faster trains and fewer delays. According to Oliver Wyman, a consultancy, the share of intermodal goods in America that travel by rail on journeys longer than 1,500 miles increases from 39% to 65% when served by a direct line.

There’s one problem with that rationale: It doesn’t depend on the merger. Instead, such benefits could be achieved in many cases via contract without the associated merger harms. (And that stat from Oliver Wyman, is not impressive: The causation might run the other way, in the sense that demand for transport on a route might cause a railroad to acquire or invest in a direct line).

The STB’s merger guidelines require prospective merging parties to answer the question of “whether the particular merger benefits upon which they are relying could be achieved by means short of merger.” If the claimed benefits from the UP-Norfolk tie-up could be achieved absent a merger, then it follows that those benefits should be given no weight in the STB’s adjudication.

An examination of the rail industry today shows that railroads can already streamline their connections between networks. Nothing prevents two railroads from contracting to facilitate deliveries between separate lines. Indeed, Jim Vena, chief executive of Union Pacific, has acknowledged that UP has a track-sharing arrangement with BNSF in the Northwest. Track-sharing arrangements like the UP-BNSF agreement allow a railroad to move freight across the rail lines owned by another railroad.

After the UP and Southern Pacific (SP) merger in 1995, UP gave trackage rights to over 3,800 miles of track to BNSF. A press release announcing the agreement stated that “BNSF will be able to serve every shipper that is served jointly by UP and SP today.” The agreement “guarantees strong rail competition for the Gulf Coast petrochemical belt, U.S.-Mexico border points, the Intermountain West, California, and along the Pacific Coast.” If UP can survive and thrive with the BNSF trackage-rights agreement, what’s stopping them from creating one with Norfolk?

A 2001 STB report analyzing the UP-SP merger stated that “BNSF has competed vigorously for the traffic opened up to it by the BNSF Agreement,” and that it had “become an effective competitive replacement for the competition that would otherwise have been lost or reduced when UP and SP merged.” The report also cites enhanced competition for shippers who previously had only one rail carrier option. A potential UP-Norfolk track-sharing agreement could allow UP to service customers in Ohio and Kentucky without needing a merger.

Track-sharing agreements can also reduce the number of interchanges necessary to deliver rail cars to customers. A railroad company with a track-sharing agreement can allow another company’s trains to move along its tracks to service customers across two different rail lines without needing to swap engines. If UP and Norfolk made such a trackage agreement, a shipper in Minnesota could already ship their product to Pennsylvania without needing to swap train engines on the way, obviating the need for a merger.

The merging parties might argue that expanding these agreements will place a strain on their train dispatching systems. When two companies make a track-sharing agreement, the “host” railroad generally handles train dispatching on its own line (see the “operations” section of this Southern Pacific trackage rights agreement as an example). The host railroad has incentive to put the tenant railroad’s train at the end of the line for dispatching. (Anyone who has ridden Amtrak knows the experience of waiting for a freight train to pass ahead of you.) Hence, track-sharing agreements might lead to sub-optimal scheduling that would be avoided if all of the trains were owned by the host railroad. Rather than making investments in their train-dispatching systems to address these issues, railroads would rather merge.

It may be the case that some coast-to-coast routes cannot be streamlined through contracts, and that there are merger-specific efficiencies. In any event, the modest gains in efficiency will have to be carefully weighed against the anticompetitive effects felt by shippers and workers.

Past Mergers Have Caused Service Disruptions

Another weakness with the purported merger efficiency is that such benefits are undermined by the experiences of prior merger. Past mergers could not guarantee service improvements in the medium term. These operational failures directly contradict the recent promises that further consolidation of the railroad industry will improve speed and efficiency.

The aforementioned railroad merger, CPKC, was completed in 2023. During May and June of 2025, the combined CPKC firm experienced widespread service disruptions after merging the two legacy IT systems. The CPKC rail network experienced elevated delays, slower average velocity, and decreased on-time performance. In a report to the STB describing the situation, CPKC explained “Unfortunately, despite intensive efforts by CPKC over more than two years to prepare for a smooth transition, the Day N IT systems cut-over encountered unexpected difficulties.”

These issues aren’t isolated to the CPKC merger. When the Class 1 railroad Conrail was split between Norfolk Southern and CSX in 1999, both Norfolk and CSX experienced service disruptions. Shippers also experienced service disruptions in 1997 from the UP and Southern Pacific merger. For these major mergers, degraded performance in the medium term seems to be the rule rather than the exception. The STB’s 2001 merger guidelines recognize this history and place less weight on merger efficiencies that could take years to be realized.

Shippers Could Face Higher Prices on Overlapping Routes

Most of the business press coverage on the merger has ignored or handwaved the overlapping routes between UP and Norfolk. The New York Times has this to say on the subject:

Because Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern do not operate in each other’s regions, the tie-up would not reduce choice between railroads in those areas. Still, the companies together accounted for 43 percent of all rail freight movements last year, according to an analysis of regulatory carload data by Jason Miller, a professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University. (emphasis added)

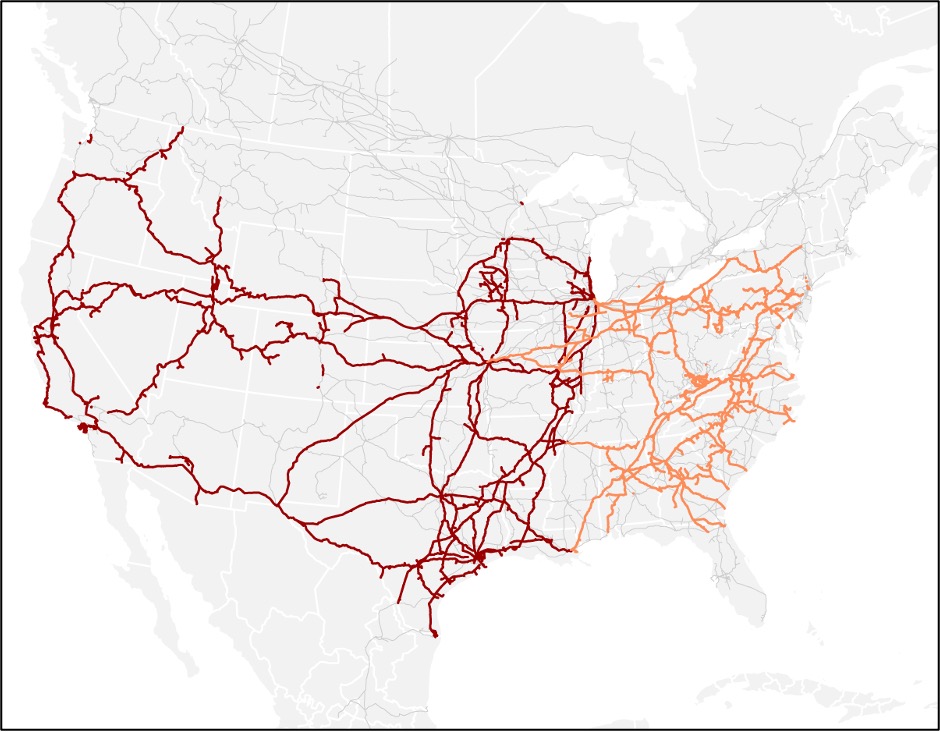

Yet the map in same New York Times story (inserted below) shows that overlapping UP-Norfolk routes exist throughout Missouri and Illinois. Shippers who need to send products from, say, Kansas City or St. Louis through Chicago will have one less option.

Note: Norfolk Southern lines are shown in orange. Union Pacific lines are shown in maroon.

The eventual rail duopoly that would result from this merger would give many shippers either one or two carriers to choose from. Some shippers may become “captive shippers” who are beholden to a single railroad (aka monopoly) for their shipping needs. These captive shippers would likely face higher prices and worse service quality.

Recently, regulators have attempted to use reciprocal switching to solve the issue of captive shippers. When a shipper only has access to a single Class 1 railroad, a reciprocal switching agreement allows another outside railroad to compete for that shipper’s contract. If the outside railroad wins the contract, the incumbent railroad facilitates the freight pickup in exchange for a fee. These agreements enhance competition for shipping contracts while also compensating the incumbent railroad for using their tracks. It’s a win for both parties.

Yet the STB has only mandated these reciprocal switching agreements when a Class 1 railroad failed to meet performance standards regarding consistency and reliability. The competition standard for captive shippers should not be whether they reach a minimum level of service quality. When considering the possibility of creating a rail duopoly in this country, the STB should contemplate expanding their use of reciprocal switching agreements to enhance competition. But this reform is not a panacea for shippers facing a railroad monopoly from a merger. A recent Seventh Circuit decision overturned the STB’s 2024 reciprocal switching rule, finding it “inconsistent with the Board’s statutory authority.” This decision shows that ensuring competition cannot be achieved solely through rulemaking.

Workers Are Right to Be Skeptical of This Deal

Per The Economist, unions might “lie on the tracks” when it comes to the UP-Norfolk merger. The resulting rail duopoly from this merger would reduce the number of prospective rail employers, and prevent the bidding up of rail worker wages by rival railroads. The likelihood of layoffs and lower wages has already caused the Transport Workers Union to oppose the merger. The Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers (SMART) union has also announced its opposition.

Despite the promises from UP’s and Norfolk’s management that they will preserve union jobs, the latest Class 1 merger should make rail workers skeptical. The recent CPKC post-merger service disruptions necessitated the temporary loaning of rail crews to address personnel shortages on their system. Yet one local SMART union alleges that the CPKC loaned crews reduced the number of yard jobs available for union employees. The local union alleges that CPKC took advantage of the service crisis to make these job changes. If that post-merger scenario is any guide, then the rail workers unions are justified in their opposition.

The Business Journalism Regarding the Deal Is Unbalanced

Despite the skepticism to the deal voiced by rail workers and shippers (the Freight Rail Customer Alliance representing over 3,500 businesses has criticized the proposed merger), business journalists seem enthusiastic about the deal. The New York Times and The Economist both trumpeted the deal, even citing the same industry analyst, Tony Hatch, in support of claimed efficiencies. Hatch’s support for the deal was widely shared throughout the business press, as he was also quoted by NPR, PBS, and the Bloomberg Podcast. Yet no message of skepticism of the merger efficiencies was widely shared in the media.

This is not to say that consulting a favorable industry expert is an issue. Yet instances like PBS gathering quotes from two analysts touting the benefits of the deal leaves readers with an unbalanced view. Our humble suggestion is that a business journalist, whether explaining a price hike or evaluating a merger, upon receiving a statement from an industry insider, should pick up the phone and seek an alternative opinion from a consumer or labor advocate (or, as a last resort, an economist not working for the merging parties).

The Surface Transportation Board Should Examine This Merger with a Skeptical Eye

The STB should ignore the glowing cheers from the business press and consider the harms to shippers and workers. This deal would likely create a transcontinental rail duopoly in this country, which would lead to even less choice for rail customers. The enhanced market power of the rail duopoly could lead to higher prices for consumers and less bargaining power for workers. Meanwhile, many of the promised service efficiencies could be gained without this merger. In light of the real costs and elusive benefits from this deal, the STB should examine the Union Pacific merger application with a skeptical eye and ensure that freight rail competition is maintained.