The wealthiest man in the world was President Trump’s largest campaign contributor, thirteen billionaires were selected for positions in the administration, and the fourth wealthiest man in the world announced that the third largest newspaper in the country would no longer publish any opinion pieces critical of free markets. As if this weren’t an already alarming indication of the dangerous connection between economic might and socio-political power, next year, the Supreme Court will hear National Republican Senatorial Committee, et al. v. Federal Election Commission, et al., a case with the potential to erode some of the last remaining campaign finance limits. If the Court embraces the petitioners’ argument that broad categories of political spending should be freed from expenditure limits, it could intensify the transformation of American democracy catalyzed by Citizens United v. FEC and related decisions.

This looming decision arrives amid a broader, heated debate about the relationship between economic concentration and political power. Neo-Brandeisians, concerned with the corrosive effects that “bigness” of dominant firms and concentrated markets may have on democracy, increasingly find themselves at odds with “abundance” liberals and traditional antitrust centrists, who argue that dominant firm size, in and of itself, may not be as large a threat to democracy as alleged.

Yet this debate takes place atop some flawed empirical foundations. At the core is an assumption that lobbying expenditure data provides a reliable proxy for measuring concentration of political power. In a new working paper, I challenge that assumption, arguing instead that the apparent lack of correlation between rising economic concentration and lobbying market concentration obscures the rise of a more diffuse, opaque, and powerful influence ecosystem, enabled and financed by the wealth created through economic concentration. In short, what we see in lobbying data is not the absence of political capture, but its concealment.

Beyond Lobbying: A Complex Architecture of Political Influence

Quantitative analyses often treat political influence as a transactional marketplace where dollars spent on lobbying translate into policy influence. But this market analogy is conceptually flawed and empirically misleading. Lobbying, as captured by the Lobbying Disclosure Act, represents only a narrow slice of the influence economy. A growing share of influence is exercised through “dark money” groups, strategic litigation, media ownership, academic funding, “astroturf” campaigns, and campaign contributions by ultra-wealthy individuals.

These alternative channels of influence are not only substitutable with traditional lobbying; they are often more effective and less transparent. For instance, wealthy actors can achieve their policy goals by funding academic research that shifts public discourse, or by supporting litigation strategies that circumvent Congress altogether. These efforts rarely show up in lobbying disclosures, making them functionally invisible to traditional metrics.

The Empirical Illusion of Stable Lobbying Markets

Studies observing low or relatively stable concentration in lobbying expenditure patterns suggest that economic concentration does not lead to disproportionate political power. For example, a recent study by Nolan McCarty and Sepehr Shahshahani, comparing two decades of Lobbying Data Act expense reports to economic concentration and revenue, found that increasing corporate revenue does not lead to a disproportionate growth in the corporation’s lobbying spend and that an industry’s market concentration does not lead to a corresponding concentration in the industry’s lobbying “market,” suggesting there is little relationship between economic concentration and concentration of lobbying power. The reliability of this conclusion rests on the assumption that measurement error in lobbying data, though incomplete, is at least stable over time. If the magnitude of underreporting or misclassification is consistent year over year, then trends in lobbying concentration should still be informative about broader political economy dynamics, even if the data are imperfect.

This assumption has intuitive appeal. Longitudinal trends in a flawed dataset can, under some conditions, reveal meaningful shifts in behavior or structure. But this defense falters upon closer inspection, because it ignores the dynamic nature of political influence and the fungibility of influence-seeking behavior across channels. In practice, actors in political influence markets routinely engage in cross-channel substitution—dynamically shifting resources between lobbying, campaign finance, judicial advocacy, and public relations—in response to legal, political, and reputational shifts. These substitutions are not random; they are deliberate adaptations to maximize influence under changing constraints.

For example, following the 2007 Honest Leadership and Open Government Act (HLOGA), which imposed stricter disclosure requirements on lobbyists, many influence professionals rebranded themselves as “strategic consultants,” continuing their work without triggering Lobbying Disclosure Act reporting thresholds. Even more significantly, after Citizens United lifted restrictions on independent political spending, wealthy individuals moved significant resources into super PACs and dark money vehicles in ways that do not appear in lobbying disclosures. These shifts render the assumption of time-invariant measurement error implausible. As the legal and regulatory landscape changes, so too does the composition and visibility of political influence-seeking behavior.

Dynamic Substitution and the Post-Citizens United Shift

The 2010 Citizens United and related rulings drastically altered the strategic calculus of political influence. It enabled unlimited independent expenditures, allowing ultra-wealthy individuals to create expansive political infrastructures outside traditional corporate channels. These donors now routinely bypass firm rent-seeking allocations and operate instead through super PACs, nonprofit advocacy groups, and partisan media.

This shift from firm-based lobbying to capital-based influence is critical. A capital-holder with a diverse portfolio of shares across multiple industries may find it more efficient to invest in ideological advocacy and policy environments that favor their overall economic position rather than through individual firms’ budget allocations for political rent-seeking. This strategy is especially potent when coordinated across issue advocacy, electoral influence, and thought leadership.

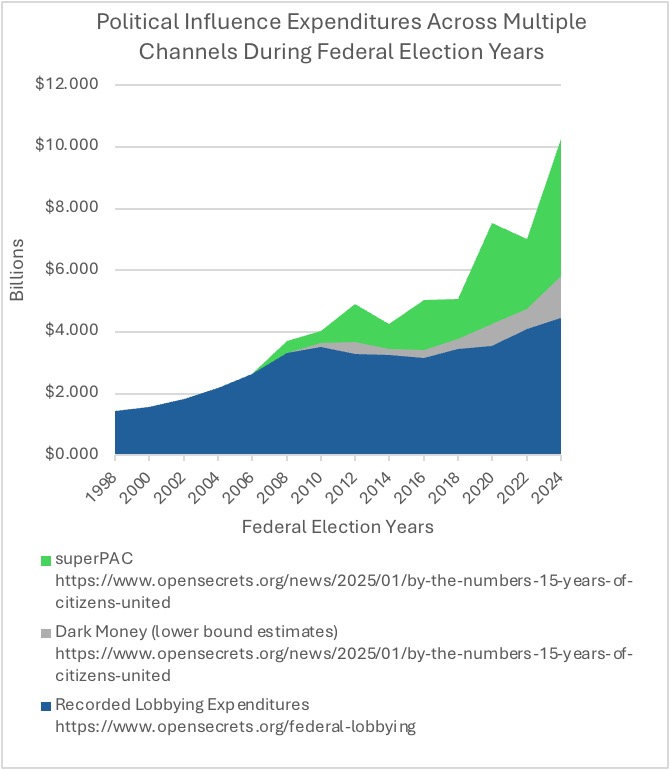

Notably, while aggregate corporate lobbying plateaued post-2010, independent expenditures by individuals and non-corporate entities skyrocketed. Consider the graph below constructed from data obtained from opensecrets.org. Using federal election years when campaign related influence expenditures are likely highest, I show that the previous exponential growth in lobbying prior to its sudden plateau may be accounted for by the explosion of alternative influence channels utilized by new forms of influence purchasing organizations made possible by Citizens United and its progeny. This divergence suggests a strategic reallocation of political investments, not a reduction in influence-seeking. It is not that political capture had stalled; it evolved beyond ostensibly observable lobbying to opaque new influence channels and beyond the firm as the principal influence market actor.

Note: All data from OpenSecrets.org

Market Concentration, Shareholder Wealth, and the Feedback Loop of Influence

The link between economic concentration and political capture is most visible in the distribution of extraordinary shareholder wealth. Dominant firms—particularly in sectors with significant barriers to entry like tech, finance, and pharmaceuticals—generate supra-competitive profits. These profits flow disproportionately to a small group of shareholders, often billionaires with significant stakes in multiple dominant firms. For example, just five companies account for over 50% of the Nasdaq index. Collectively, their market cap is worth over $16 trillion, and their profit margins range from 10% to over 50%.

Moreover, the top 1% of households now control over 50% of U.S. corporate equities, the top 10% own nearly 90%, and dominant large-cap firms drive the returns from that equity. This extreme skew ensures that shareholder value maximization, often invoked as the corporation’s principle purpose, effectively channels wealth to a small elite. To wit, Elon Musk just secured a $29 billion payment from Tesla, despite the electric vehicle company’s sliding sales, in part due to Musk’s politics that are antithetical to electric vehicle consumers. This elite, in turn, finances the ideological and institutional infrastructure that resists regulatory or redistributive reforms, reinforcing both economic and political concentration.

For example, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and the Koch brothers derive the vast majority of their wealth from dominant firms in their respective sectors. Through a mixture of campaign contributions, media control, and think tank funding, these individuals have become central players in shaping the policy landscape, far beyond what traditional corporate lobbying would suggest. For example, the over $290 million spent by Elon Musk on influencing the 2024 election included direct campaign contributions as well as $240 million funneled into Musk’s own America PAC and $50 million toward political ads through Citizens for Sanity PAC. Musk has leveraged his acquisition of X (formerly Twitter) to support conservative and ultraright political forces worldwide, with the Associated Press finding that Musk’s engagement can result in political hopefuls gaining millions of views and tens of thousands of new followers on his platform. When Jeff Bezos acquired The Washington Post in 2013, he pledged journalistic independence. However, in early 2025 he directed that the Opinion section “write every day in support and defense of” free markets. In conjunction with Meta, Mark Zuckerberg has donated hundreds of millions of dollars to colleges and universities like MIT and UC Berkeley leading to concerns about how such largesse may influence research agendas. The billionaire Koch brothers fund a network of 91 think tanks and organizations including the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation that often promote “pro-business” viewpoints.

Reassessing Political Influence in a Multi-Channel Ecosystem

Researchers must move beyond single-channel metrics like lobbying data and adopt frameworks that capture the full architecture of political influence. This includes recognizing the strategic complementarities and dynamic substitution between campaign contributions, dark money issue advocacy, judicial influence, media ecosystems, and think tank networks. Influence is now wielded across a portfolio of channels, often in coordinated fashion and backed by extraordinary wealth.

Just as antitrust scholars recognize the importance of cumulative advantage and non-price effects in assessing market power, political economists must account for the structural and cumulative nature of influence. Political power is not merely purchased in discrete transactions; it is cultivated over time, embedded in relationships, and reinforced through systemic advantages in access, ideology, and information.

From Misdiagnosis to Reform

The forthcoming Supreme Court decision in NRSC v. FEC threatens to further erode transparency in an already opaque political economy. To understand and confront the risks this poses, we must discard the illusion that political power can be adequately assessed through lobbying data alone. Political capture in the post-Citizens United era is no longer primarily the domain of corporations, which were only ever a proxy for the profit interests of their owners—it is the domain of capital.

Abundance liberals risk sleepwalking into this moment. By focusing only on the consumer-welfare concerns of prices, output, and innovation, they miss the broader political implications of concentration. They treat economic and political power as separate, when in fact they are intertwined in a dangerous feedback loop.

Economic concentration produces wealth inequality; that wealth finances multi-channel influence; that influence protects the structures that maintain concentration. This isn’t a conspiracy; it’s a rational response to a regulatory environment that allows wealth to become political power. Addressing this risk does not mean we have to choose between bigness or democracy, a false dichotomy suggested by some of the debate between Neo-Brandeisians and supply-side abundance liberals.

Policy tools exist that can break the cycle of capture by the wealthy and minimize the democratic harms associated with concentration, while insuring that economies of scale actually deliver abundance. We need, among other things:

- Stronger antitrust enforcement to disperse economic power at its root.

- Wealth taxation that curtails the accumulation of influence capital.

- Campaign finance reform that restores public trust in electoral fairness.

- Media ownership rules that prevent consolidation of ideological gatekeeping.

- Enhanced transparency across all channels of political influence, not just lobbying.

- Academic disclosure standards that flag financial conflicts in policy research.

- Civil society watchdogs with the resources and access to investigate hidden influence.

- Legal reforms that broaden the definition of lobbying to include consulting and strategic advisory work.

The debate between Neo-Brandeisians, abundance liberals, and consumer welfare centrists is not merely theoretical. It reflects competing visions for the future of American democracy. If policymakers and scholars continue to underestimate the evolving architecture of political power and ignore the direct evidence of political capture by concentration-enabled capital, they risk providing rhetorical support for even further degradations to democratic responsiveness. The real threat of “bigness” isn’t just economic inefficiency. It’s the quiet capture of democracy itself.

Randy Kim is a municipal government attorney whose research and advocacy interests include economic justice, labor rights, the political dimensions of concentrated economic power, and their intersections. Opinions expressed herein are the author’s own and do not reflect the positions or opinions of his employers.