If I had a dollar for every New York Times business story that attributed an industry-wide price hike in the post-Covid era to an outward shift in demand—that is, a story that blamed consumers for higher prices—I’d have, like, 25 dollars. Since the post-Covid era, the Times in particular, and the mainstream business press in general, have been feeding us a steady diet of demand-driven inflation explainers.

The latest installment of this neoliberal series came via a story on why rates for Vegas hotel rooms are surging. The Times reports that in August 2019, the average daily room rate in Vegas (before resort fees) was $120.96, but has since climbed to $162.38 by 2025, an increase of 34.2 percent or about five percent per year. (Another data series shows the average daily room rate rising from $133 in 2019 to $194 in 2024, an increase of about eight percent per year before considering the drop in rates in 2025.)

Per the Times’s telling, backed with an expert economist, Vegas hotel rates are soaring because … wait for it … tourists are engaged in “revenge travel:”

By mid-2021, the city was back with a vengeance. Demand for pool reservations, college basketball tickets and hotel bookings surged as travel rebounded. Prices rose. In August 2019, the average daily room rate was $120.96. This year, it was $162.38. But rates go much higher. The Venetian, for example, offers rooms as high as $1,112 — and that’s before resort fees. The surge in revenge travel said Mr. Woods, the U.N.L.V. professor, led the resorts to raise prices because of increased demand.

The story doesn’t explore any other hypotheses, especially those that might put the onus back on the hotels. Never mind there was significant antitrust litigation against Cendyn, maker of Guest Rev software, alleging that the Vegas hotels use a common pricing algorithm that facilitates coordination and thereby permits hotels on the Vegas Strip to reach the jointly profit-maximizing price. That this challenge was not legally successful based on a horrible ruling by the Ninth Circuit—even Herb Hovenkamp thinks it horrible—doesn’t mean that outsourcing one’s prices to a common pricing consultant has no impact on hotel rates.

(The Sling will have much more to say on this horrible decision in a bit!)

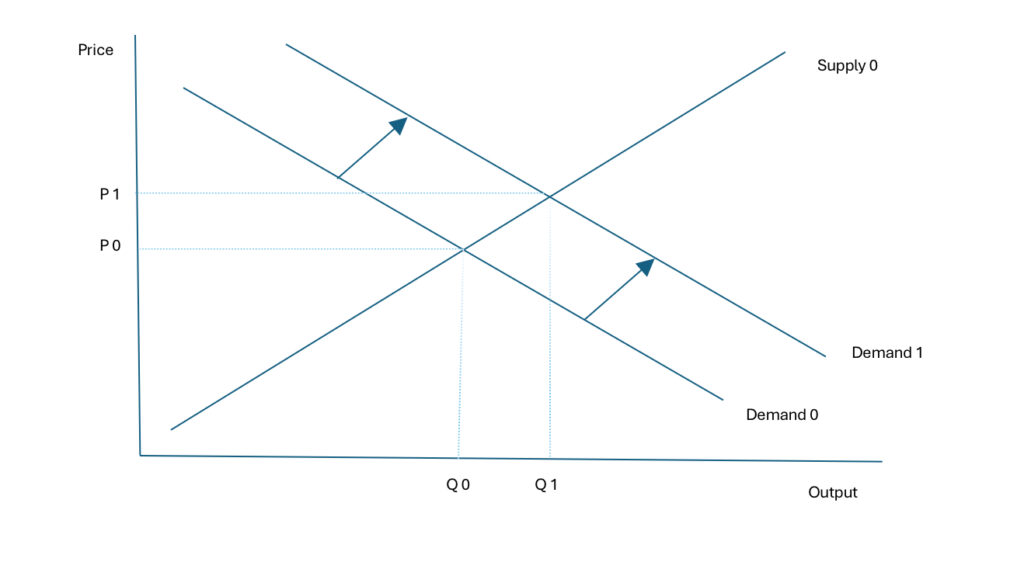

How can we rule out the demand-based explanations peddled by the UNLV economist? If hotel rates are going up because an outward shift in the demand curve, we’d observe both an increase in rates and an increase in rooms rented (output). The figure below shows what happens when demand shifts outwards, holding supply constant.

When demand shifts outward from Demand 0 to Demand 1, prices rise from P0 to P1 but also output increases from Q0 to Q1.

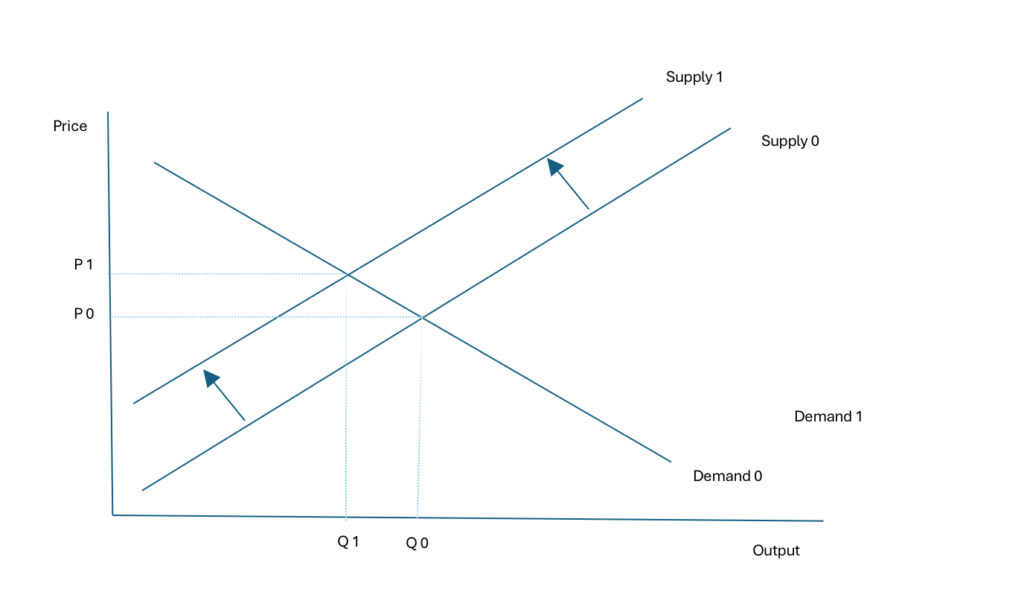

What else can explain an increase in prices? Let’s see what happens when instead the supply curve shifts inwards, holding demand constant, say as a result of a coordinated drawdown in room availability made possible through a common pricing algorithm.

When supply shifts inward from Supply 0 to Supply 1, prices again rise from P0 to P1 but also output decreases from Q0 to Q1.

Where could one go to find evidence of an output reduction? That’s right, in the same Times story peddling demand-based explanations:

Throughout those many versions, Las Vegas had largely endured as an affordable destination, with reasonable hotels and all-you-can-eat buffets. But in its latest iteration, the city is in the midst of a tourism downturn, with an 11 percent decline in visitor volume since last year, according to the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority.

Now visitor volume might not exactly mirror hotel rooms rented but it’s a good proxy for that figure. If visitors believed that rates were too high, they would cut back on visiting Las Vegas, reducing hotel occupancy rates. Fortunately we don’t have to guess: Per the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, in 2019, city-wide occupancy was 88.9 percent, but by 2024, occupancy on the Las Vegas Strip had declined to 86.4 percent. In the first half of 2025, occupancy on the Strip was 81.9 percent. Because the supply-side contraction predicts a decline in output, the supply-side story is more compelling than the demand-side story peddled by the Times.

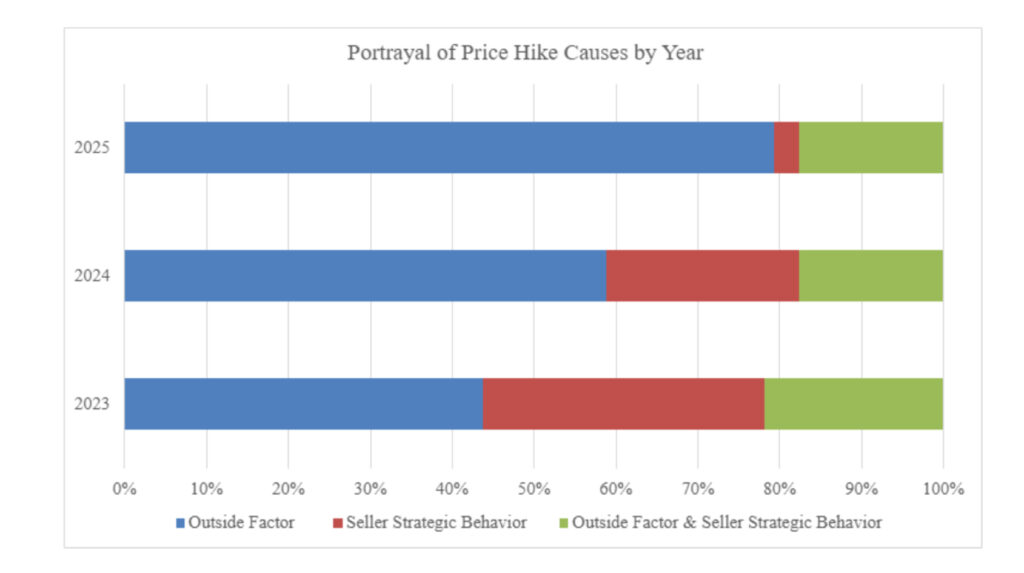

If this were just a one-off episode, I’d let it go. But since the onset of inflation in the post-Covid era, the Times and mainstream business press have been feeding us a steady diet of blame consumers or blame workers or blame just about anyone or anything but the folks who are actually setting prices. In a new study, co-authored with a rising Yale senior, Abla Abdulkadir, we examined a dataset of articles discussing price hikes across industries from nine publications: The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Economist, Politico, Financial Times, CNBC, Bloomberg, and Axios. We then manually analyze a smaller subset of these articles in order to determine how they discuss what motivates rising prices and their overall portrayal of seller behavior. From this manual analysis, we determine that in the majority of cases an outside factor is cited, to varying degrees, as the motivator of price hikes. Here’s a preview of what we found.

The figure above shows a breakdown of price hike causes by year. The blue category on the left, “Outside Factor,” represents the largest category. Stories in this category increased over time, growing from a little over 40 percent in 2023 to nearly 80 percent by 2025.

Our advice for business reporters is to speak with more than one economist, especially if your source has financial ties to the industry under study. Be especially dubious of public relations consultants who are paid to peddle industry talking points, lest you end up carrying that same water. (The Times coverage of the predicted price effects of the pending Union Pacific-Norfolk Southern railroad merger is a case in point.) And if your sources keep peddling demand-based theories, ask whether output has also increased; if it hasn’t, then first ask them why and then consider alternative explanations, including those that shift the onus back on the sellers.