One of the favorite jabs of the left-punching commentator community—from Matt Yglesias, Alex Trembath, and the abundance-flavored podcast “Everyone Gets Pie”—has been to accuse progressives of being “Degrowthers.” While degrowth as a framework has been around for a while, its extremely limited presence in the zeitgeist is a relatively recent phenomenon. Modern progressives are not anti-growth; they simply recognize that growth by itself can’t solve inequality and other social problems. (As Noah Smith wrote, degrowth’s only real influence is in Europe.) The Growthers are punching at shadows.

A profile in the New York Times from last year is illustrative. Among the assortment of degrowth champions included, the only American mentioned (economist Herman Daly) has been dead for three years. Indeed, even among left-wing economists, there’s very little support for degrowth. Prominent economist Jayati Ghosh dissected the degrowth argument from Kate Soper—one of the prominent degrowth luminaries highlighted by the Times—in Boston Review in a piece whose title did not mince words: “Degrowth is a Distraction.”

Even among environmental champions, hardly anyone is advancing degrowth-oriented economic policy. Even the much maligned Green New Deal spearheaded by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ed Markey was not remotely degrowth; it still envisioned a greened economy through the lens of a growing economy, including expanding jobs and opportunity and leaning into the “social cost of carbon,” a market-based mechanism to influence emissions via price pressure.

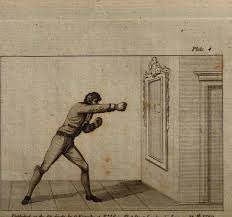

That, though, is the beauty of boxing with shadows: you don’t have to worry about taking a punch.

Judging from how often the “degrowth” label is thrown around to malign progressives, however, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the entire progressive movement now proudly championed it. Particularly in light of the intra-left sparring over whether to lean into antimonopolist economic populism or abundance liberalism, degrowth is frequently invoked to paint those aligned with the antimonopolist/populist line as pro-scarcity. In reality, the word hasn’t even been used enough in news coverage to show up in Google’s trend analytics.

Undeterred by reality, Matt Yglesias has characterized the constellation of abundance critics as “degrowth environmentalism and the many, many strands of progressive organization that claim to be something else (like economic populism) while in practice just serving as skin suits for degrowth environmentalism.”

As Lee Hepner of the American Economic Liberties Project has pointed out, this (bad faith) critique presents a dichotomy where one needn’t exist. This characterization serves only to flatten a multi-dimensional topic into an either or proposition. Most of the time, someone arguing against maximal growth is not, in fact, pushing for degrowth. Rather, they generally are making a case for why foregoing some growth is an acceptable cost to achieve another policy objective. Or, why a particular instance of growth is actively harmful, or that growth by itself can’t solve many of society’s problems.

This shouldn’t be a controversial position; society makes these kinds of determinations all the time. Coca-Cola’s demand curve was probably a little bit more conducive to growth back when it had cocaine in it. We could probably increase bread production if we once again let bakers cut the flour with sawdust. Is banning those harmful inputs degrowth? Obviously not. We can acknowledge that maximal growth can go against other priorities we care about and cause human costs.

All this line of argument boils down to is that externalities matter.

In his essay first proposing an “abundance agenda,” Derek Thompson wrote that growth is an objective “not because growth is an end but because it is the best means to achieve the ends that we care about: more comfortable lives, with more power to do what we want, with more time devoted to what we love.” I think that’s precisely correct. But the implication of Thompson’s case is that growth is good, insofar as it makes people’s lives better. So it follows that when, at the margin, growth produces more harm than benefit, growth is no longer our aim.

Growth is responsible for the widely shared prosperity ushered in across much of the world in the twentieth century, leading to declines in infant mortality, longer life expectancy, and some of the best standards of living in human history. But growth has also driven mass deforestation, soaring income inequality, and the erosion of democracy as power became increasingly concentrated. When a handful of companies control local television stations, it’s easier for a president with authoritarian tendencies to punish his perceived enemies. Acknowledging that duality and seeking balance is different than monomaniacally pursuing economic growth or degrowth.

Demystifying Degrowth

I personally am not a believer in degrowth; I think that the objective ought to be to reorient economic growth away from extractive practices and towards types of production that can be sustained by renewable resources. Many ecosocialist critiques of capitalism center on the mismatch between the Earth’s finite resources and the presumption of infinite growth. I think that this gap can be mostly reconciled by gradually creating economies that emphasize things like knowledge production and the provision of social services, along with cultivating essential resources that can be replenished. That’s a far off pipe dream, but at this point, so is any meaningful implementation of a degrowth approach.

But if degrowth is taken in the expansive sense used by some advocates of the abundance agenda, then degrowth is anything that moves away from the maximum possible economic expansion. Taken to its logical extreme, this would mean that any approach that is not as resource-intensive as possible would be degrowth, because you are reducing demand for whatever the relevant inputs are and thus not creating the incentive for more resource production. Curing a disease would be “degrowth” under this metric; treating the symptoms would sustain a consumer’s (inelastic) demand for pharmaceuticals and medical care, whereas curative care is finite. But we don’t go around asking people to live with chronic diseases in the name of juicing aggregate demand.

For example, opting to hang laundry outside on a clothesline rather than always using the dryer could be construed as “degrowth.” It decreases the wear on the drying machine and clothes, making them last longer, thereby reducing the demand for new dryers and clothing, and can result in less need for maintenance, reducing the demand for appliance technicians. If tens of millions of people shifted to using clotheslines, that would translate into lost jobs and income, which would then further reduce total consumption. But degrowth shouldn’t sound scary if it’s just hanging your clothes up to dry.

In a bigger picture sense, degrowth is often about identifying ways to shift from production for profit, which makes allocation decisions based on maximizing returns, to production for use, which makes allocation decisions based on need. But degrowth generally doesn’t seek to simply slash living standards across the board. Rather, it would look for instances like our clotheslines, where it’s relatively easy to substantially reduce resource-intensiveness without immiserating everyone.

Barring a societal collapse, wholesale degrowth seems unlikely. But under the strawman that neoliberal pundits have constructed to try and tar antimonopolists, we do degrowth every day. Every time you wear a sweater an extra time before washing, every time a doctor cures a patient, or every time someone grows their own herbs or vegetables, they are engaging in “degrowth.”

Costs and Benefits

Often in economic analyses, costs and benefits are denominated in terms of how much growth would be stimulated. But that elides that there are costs and benefits to growth as well.

Far too often, growth has been allowed to eclipse non-monetary harms. In the name of economic growth, we have built polluting infrastructure that condemns entire communities to cancer, ignored soaring income inequality, and undermined the fabric of society.

This is why distribution has to be considered alongside growth. If an economy creates $100 billion in value annually but 90 percent of that goes to the richest one percent of people, is that actually better than creating only $50 billion if that is then distributed evenly across the population? The authors of Abundance assume, in their sci-fi (or perhaps more high fantasy) opening vignette, things like the growth from AI will being equitably shared–but, c’mon, Andreessen and Musk and Altman and Thiel and Huang–NONE of them are going to share anything without state coercion against which they will fight like hyenas.

Relative well being matters a lot in social relations. Most of the time, we judge ourselves in relation to the other people we see in the world. Humans care about fairness; extremely pronounced inequality necessarily makes people feel worse off.

The immense appeal of “growing the pie” or “a rising tide lifts all boats” is that if it’s true, economic policy can be oriented around a single overriding objective. The nitty gritty work of shaping market structure and tax codes becomes tinkering around the edges.

But this single-mindedness overlooks the very real harms of widening inequality and becoming reliant on unsustainable production models.

Growth As a Means Not an End

The pursuit of economic prosperity in a real sense requires that growth be properly understood as a means, not an end. Indeed, many of the most cutting socialist critiques of a growth-oriented economy is that the drive for accumulation becomes totally detached from the real reasons we want growth in the first place.

To overcome such obstacles will require interrogating market structure to question whether growth actually serves the common interest. Many times, economic development has been used to justify a race to the bottom, where communities mortgage their future for hollow promises of jobs and investment that may be fleeting or illusory. Take Iowa’s investment in John Deere. The state provided incentives in excess of $270 million and the company still opted to substantially reduce its workforce across the state.

Rather than allow degrowth to continue to haunt the imagination of our political discourse, we should embrace an understanding of growth as an instrument of progress. As such, we can acknowledge that it interacts with other policy considerations, rather than overriding them. If we want growth because it makes people healthier, happier, and freer, then it is a public disservice not to weigh consequences that might undermine health, happiness, and freedom.

Avenging Antimonopolists

Characterizing antimonopolists as degrowth is particularly risible, as the entire point of antimonopoly politics is actually about maintaining a competitive equilibrium in the interest of long term stable growth. The premise of fighting monopolies is that in markets that are not concentrated, firms have to compete against each other, which drives innovation and risk-taking, the engine of economic progress.