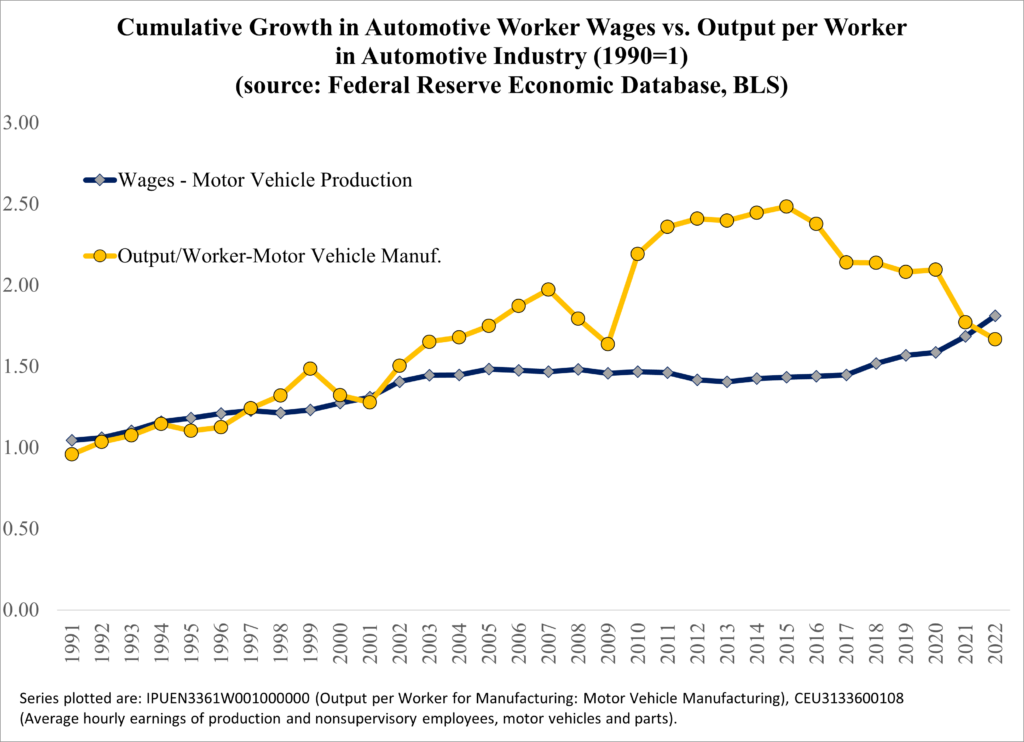

You might have read the latest pablum from the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip, arguing that autoworkers don’t deserve higher wages because America’s automotive workforce “just isn’t productive enough.” Ip, WSJ’s chief economics “commentator” offers as his evidence the recent decline in output per worker (he provides a graph that starts only in 2009, an interesting decision as the data begin in approximately 1990). So, let’s take a look at the data.

The graph above begins in 1990 with values of 1 for each variable. I then apply the annual percentage changes in each variable, tracing the cumulative changes until 2022 so that we can observe the cumulative effect. As you can see, the problem is the opposite of what Ip claims. Wages didn’t keep up with productivity.

For the decade 1990-2000, changes in worker wages closely matched changes in productivity, as one might expect. This changed with the George W. Bush presidency. Beginning in 2001, worker productivity (output per worker) began outpacing wages. In fact, the disparity became so great that that the overall increase in worker productivity was 1.73 times higher than the wage increase by 2015.

Unrewarded, productivity began to decline – by 2020, cumulative productivity growth declined to match the wage growth. But why should it not? Workers increased their productivity for nearly 20 years without seeing a commensurate increase in wages. If anything, these data suggest that automakers wield monopsony power over their workforce, suppressing wages below the marginal revenue product of labor. Meanwhile, executive pay has skyrocketed: 3 automaker CEOs received a combined $75M in pay in 2022.