On November 1, Judge Florence Pan blocked the Penguin-Random House/Simon & Schuster merger. The Department of Justice’s primary theory of harm was that the merger would harm book authors by reducing advances. The decision prompted economist Hal Singer to ask his Twitter followers whether “the consumer welfare standard—which ranked consumers over workers in the antitrust hierarchy and fixated over short-run price effects—is officially dead?” (The written decision was unsealed on Monday, and the Court concluded that the acquisition “is likely to substantially lessen competition to acquire ‘the publishing rights to anticipated top-selling books,’ which comprise the relevant market in this case.”)

In a series of tweets responding to Singer’s question that echoed his recent scholarship on this subject, leading antitrust law professor Herbert Hovenkamp argues that the consumer welfare standard is very much alive and can accommodate harms to labor. For Hovenkamp, consumer welfare properly understood is a maximum welfare prescription, and thus already takes into account worker interests. While acknowledging that anticompetitive restraints on workers like non-compete and no-poaching agreements do exist, he asserts that these are ultimately secondary to, and should be subordinated under, labor’s alleged larger interest in maximum output in product markets, where its interests happen to align with consumers anyway. In other words, the status quo is fine.

Leaving aside the nearly one in five workers subject to non-compete agreements, who might disagree that labor market restraints are a secondary concern, it’s important to note at the outset how surprising Hovenkamp’s claim would be if it were true. In Hovenkamp’s telling, the coming of the consumer welfare standard in the 1980s rescued antitrust from the bad old days of overaggressive enforcement in the 1960s. However, 1980 happens to be about the time that wages started stagnating, after historically robust growth from the end of World War II into the 1970s. If consumer-welfare antitrust actually did help workers, the effects were so weak that they were swamped by the other policy components of neoliberalism happening at the same time.

But since we can’t rerun the last forty years with everything else held constant except the consumer-welfare revolution, let’s assess Hovenkamp’s case on its own merits. The argument is a simple one: labor is an input into production, and the demand for labor is ultimately derivative of the demand for products. Therefore, maximum output in product markets should not only lower prices for consumers, it should also raise the demand for labor, which would increase both employment and wages. In Hovenkamp’s words:

When product market output is strong and demand is growing, the fortunes of labor rise as well. Here, consumers are very largely in the driver’s seat. They make purchase choices, which in turn determine demand and thus the need for labor. So labor rides on consumer choice.

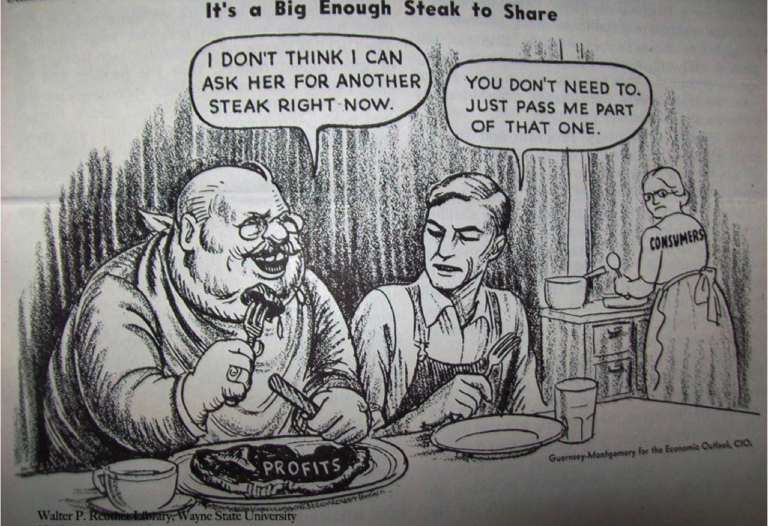

It would indeed be nice if any opposing interests of consumers and labor could be dissolved through the solvent of maximum output, with consumers winning first but labor nonetheless along for the ride. Alas, it is not so. Distributional conflicts, especially in the antitrust domain, are not so easily avoided.

Output expansion or economic growth is desirable because it has the ability to increase the size of the economic pie, allowing us all to have bigger slices without altering anyone’s relative shares. Hovenkamp is right that strong and growing demand is good for labor at the macroeconomic level, as strong aggregate demand means low unemployment and high worker bargaining power. But aggregate demand is determined by fiscal and monetary policy, not by “consumer choice.” While consumer choice does influence the allocation of demand between this or that good or service, it has no influence on its level. Consumers cannot will demand into existence in a depressed economy in which income and credit are hard to obtain.

When applied to antitrust, Hovenkamp’s desire to shoehorn worker welfare into an epiphenomenon of consumer welfare runs into insurmountable problems. In many instances, antitrust is asked to weigh in on wealth transfers between employers, consumers, and workers. Interests do conflict in the real world, and a monomaniacal focus on consumer welfare assumes away the wealth transfers that are paramount in many cases. Where anticompetitive conduct redistributes wealth from one side of the market to the other—the very cases that antitrust (and all) litigation is concerned, otherwise they would not be litigated—the maximum output rule offers no useful guidance. As a result, with consumer welfare as its lodestar, antitrust doesn’t have anything to say about a merger that would cause such a redistribution from labor.

Hovenkamp’s main case for the unity of worker and consumer interests rests on theories of classical labor monopsony with a uniform wage rate, a special case of monopsony where worker and consumer interests do actually align. Under this model, employers do not take wages as given by a perfectly competitive market. Rather, they have some discretion to set wages by selecting a point on an upward-sloping labor supply curve. While this allows them to pay workers below their productivity, it also makes them reluctant to hire more workers. Because classical monopsonists make so much profit from paying their current workforce less than their productivity, they don’t want to institute the uniform wage increases necessary to attract additional workers. The reason is that a higher uniform wage would mean raising wages for their currently underpaid workers as well. In classical monopsony, output is less than it would be under perfect competition: the outcome is not just an unfair redistribution from workers, it shrinks the size of the overall pie. Under classical monopsony, a maximum output rule would benefit both consumers and workers.

In this highly stylized model of the labor market, it is the power of workers to enforce the social norm of “equal pay for equal work” that actually creates the output-shrinking inefficiency: were the classical monopsonist able to pay each worker an individualized wage (as algorithmic management techniques increasingly allow employers to do), output would actually rise to the perfectly competitive level and the output reduction would disappear. But the unfair and unjust redistribution from labor would remain—employers and consumers would benefit, but workers would lose. In this case, a maximum output rule would benefit both consumers and employers, at the expense of workers.

Moreover, outside the strict assumptions of the classical monopsony model, buyer power in labor markets has the potential to increase output. Monopsony power is a function of workers’ outside options: the more limited the choice of employers, the greater the power of the employer over labor. Classical monopsony focuses solely on the wage rate. But employers don’t care only about wages. As economists from Karl Marx to Carl Shapiro and Joseph Stiglitz have long recognized, labor is a unique input in that “labor supply” does not capture what employers are really after. While the wage rate buys employers a workers’ time, what employers really want is effort. No one hires you for a job just to sit there for eight hours. And effort, just as much as wages, is a function of workers’ outside options: the more limited your choice of employer, the more you fear being fired, and the harder you will work to avoid that outcome. A merger in a labor market or a non-compete clause could therefore raise output—by making each employee work harder.

This is not a mere theoretical curiosity. There is evidence that hospital mergers harm nurses not by lowering their wages, but rather by increasing the number of patients for whom they must provide care. Nurses working harder can raise output and lower prices. Or take the example of Amazon: While it likely uses its monopsony power to pay workers less than their productivity, what it really excels at is extracting literally superhuman effort levels from each worker. The evidence is plain to see in the soaring musculoskeletal injury rates, caused by a super-fast pace of work. Should a hospital merger that increases output by lowering staffing ratios be waved through under a maximum output standard? It turns out there is simply no avoiding these distributional issues, and a “maximum output” rule does not resolve them.

Turning to specific antitrust policies, Hovenkamp singles out two for special opprobrium: the Robinson-Patman Act (RPA), and prohibitions on maximum resale price maintenance (RPM). In the consumer-welfare era, federal government enforcement of the RPA has virtually ceased, and maximum RPM has been permitted under the rule of reason since 1997. However, the RPA did protect workers, but in two ways that are contrary to the logic of output maximization.

First, a properly-enforced RPA would have prevented large retailers like Walmart from out-competing smaller competitors through raw buyer power over suppliers. RPA prohibits the extraction of discriminatory price discounts from upstream suppliers without a lower cost justification. This closes the growth channel through the ability to extract special discounts not available to competitors, but keeps open the growth channel deriving from superior productive efficiency.

Continued robust enforcement of the RPA, by preventing Walmart from squeezing upstream suppliers for price discounts, would have protected workers in a slew of upstream manufacturing jobs that have now been decimated by Walmart’s massive buying power. While the output-suppressing effects of classical labor monopsony are rooted in there being a tradeoff between employee quit rates and the wage rate, these effects do not cross over to monopsony power over non-labor sellers like suppliers to large retailers. In these cases, the buyer is likely to use their power to demand (and receive) more output at lower prices. Once again, buyer power in supply chains may raise output and reduce prices (if Walmart passes its gains on to consumers), but at the expense of firms and workers upstream in these supply chains. This kind of buyer power accounts for perhaps a full ten percent of wage stagnation since the 1970s—about the time RPA enforcement ceased. Once again, this is a distributional conflict that can’t be wished away.

Second, continued enforcement of RPA could also have protected retail jobs at Walmart’s higher-wage direct competitors from this kind of unfair competition. As we now know, Walmart’s entry into local retail markets on the back of RPA violations (along with union-busting and other unfair competitive tactics) has suppressed local wages, even if it raised its own profits and boosted the output of cheap goods. The classical labor monopsony channel was overwhelmed by Walmart’s broader monopsony power over its supply chain. One could argue that the gains to consumers outweigh the harms to workers, but not that their interests are identical.

Turning to maximum resale price maintenance (RPM), the workers affected by these policies certainly do not gain from “maximum output.” In fact, franchisors and other upstream firms use RPM to enforce a low-wage business model on the downstream firms under their control. McDonald’s may well be able to sell more quarter pounders for lower prices under maximum RPM, but at the expense of workers at McDonald’s restaurants. In franchising industries, what vertical restraints like RPM do is enforce a low-wage business model on downstream franchisees, by taking virtually every variable affecting profits out of the franchisees’ choice set—not just prices but suppliers, business hours, and product mix. The effect is to force franchisees to focus intensively on the one variable they can control—lowering labor costs. As one McDonald’s franchisee explained to the Washington Post, when she complained to McDonald’s about its RPM policies the company told her to “just pay your employees less.”

While Hovenkamp seeks to outsource the goals of antitrust law to economic theory, I have argued that economics does not support “just maximize output” as a solution to question of advancing labor’s interests. But even if economics did support Hovenkamp’s claims, the legislative history of of the Sherman Antitrust Act makes it clear that its authors were simply not concerned with neoclassical economic concepts like consumer welfare or maximum output. To the extent these theoretical constructs existed at the time, they were ignored by legislators. Rather, Congress wrote the Sherman Act to guarantee to every person the opportunity to succeed or fail in the market on the basis of fair competition, limit the political power of the wealthy, and, most relevant to our purposes, prevent unfair wealth transfers from consumers, farmers, and labor to large corporations and cartels. In other words, Congress was concerned with the distribution of wealth, power, and opportunity.

Economics does have a role to play in antitrust. Power, wages, prices, and yes, output are all quantities, that must be accurately measured and quantified to help inform new legislation in Congress and competition rulemakings by the Federal Trade Commission. And whatever criticisms one might level at economists, no one else has stepped up to develop better techniques for quantification than us. But neoclassical economic theory cannot be the solvent some want it to be. Economic theory cannot provide the normative values antitrust agencies and courts must use to evaluate competitive conduct, particularly where labor is threatened but consumers are not. Only a democratic legislature can do that. And Congress specified other goals than maximum output when it wrote our antitrust laws.