Amazon Prime Day and Black Friday have become de facto national holidays of impulsive shopping, ostensibly offering a bevy of “great deals” to tempt consumers. A flood of media articles accompany this celebration of capitalism that masquerades as an event worthy of news coverage. Legions of outlets receive compensation from Amazon in exchange for driving traffic to its platform, often by offering “advice” on the best bargains to snag (e.g. CNN Underscored).

But, as some have already noticed, those advertised promotional discounts can be a mirage and often offer higher price than those regularly found throughout the year. Rather shockingly, even an article on the Washington Post, which Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns, acknowledged this, with the author explaining that “I would have saved, on average, almost nothing during Amazon’s recent fall “Prime Big Deal Days”—and for some big-ticket purchases, I would have actually paid more.” Even so, Prime Day 2025 was Amazon’s biggest ever, with record sales and volume.

In the past few months, I took a deep dive into algorithmic pricing, the machine learning methods used, as well as various case studies, including how repricers work in conjunction with Amazon’s Buy Box to raise prices. Repricing algorithms on Amazon and their interaction with Buy Box rotation indicates that focusing exclusively on common pricing algorithms misses the risk of industry-wide algorithmic standardization. Even though sellers on Amazon can use various repricing providers and even though they may not share competitively sensitive information, the outcomes on Amazon still reflect supra-competitive prices, similar to those achieved from explicit coordination.

Price discrimination is just the tip of the iceberg

Recently, an investigation by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) found that school districts paid widely varying prices for the same products often on the same day, a practice known as price discrimination. While the report focused on schools specifically, businesses that purchase on Amazon should pay attention as well. Segmenting business purchases from those made by consumers is an example of third-order price discrimination.

Employees making purchases for their employer may be less price-sensitive than when making purchases for themselves, allowing Amazon to charge higher prices to the former. Those higher prices eventually get passed on to those businesses’ own consumers, adding to inflationary pressure. Those advocating for lower interest rates would do well to concern themselves with such pricing practices.

The ILSR report attributed the pricing variance it found to Amazon’s opaque dynamic pricing algorithm, the details of which I want to address here. Millions of sellers market their products on Amazon so, of course, one might think that the pricing discipline they (should) exert on each other would result in competitive prices for consumers. After all, as the Lending Tree commercial reminds us, “when banks compete, you win”. So, why aren’t consumers really winning? Why are prices going up?

In my new paper, I discuss the role of algorithms in pricing as well as the various machine learning tools used to implement them in various industries, including E-commerce, hospitality, airlines, real estate, and others. I also talk specifically about pricing on Amazon, which involves the relationship between rules-based and machine learning algorithms.

How repricers’ algorithms interact with Amazon’s Buy Box

On this topic, there’s another factor at play that has flown comparatively under the proverbial radar: the role of Amazon repricers’ respective algorithms and how their interaction with Amazon’s “Buy Box” algorithm enables successful price hikes. Repricing refers to the process of dynamically changing the offer price according to various guidelines. Many companies such as Repricer.com, BQool, Seller Snap, Flashpricer, and Amazon’s own Automate Pricing repricer offer this service.

The Buy Box, now called the “Featured Offer” on Amazon, refers to the box that appears on the right of an Amazon page prominently, displaying the price and shipping details for the seller who currently holds the Buy Box for this product. To see other competing options, a consumer needs to click on “Other Sellers on Amazon,” which appear on a pop-up page.

Not every seller is eligible for the Buy Box—Amazon imposes various eligibility criteria, including prioritizing its own delivery service, Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) over Fulfillment by Merchant (FBM), conduct that prompted an investigation by the European Commission.

Needless to say, the vast majority of purchases, around 80 percent, occur though the Buy Box, which is why sellers want to secure it. Eligibility criteria also matter, because eligible sellers can choose not to compete at all with sellers of the same product, such as those that do not qualify for the Buy Box. So, that seemingly vast landscape of competitors just got smaller. And note that we’re talking about two different types of algorithms that work in concert: Amazon’s algorithm to determine the Buy Box winner and the repricing algorithms that sellers use to set prices.

Repricing on Amazon offers a particularly interesting case study of algorithmic pricing because (1) sellers can use different repricers, (2) repricers can use different algorithms, AI-based (i.e., machine learning), simple rules-based algorithms (e.g., if-then-else statements), or a combination of both, and (3) though sellers can obtain their own data and limited competitor information using the Amazon SP-API, (e.g., though the getcompetitivesummary call), no obvious sharing of competitively sensitive information occurs. In other words, the conditions that have garnered the most focus in algorithmic pricing cases such as the RealPage litigation and Gibson v. Cendyn, do not seem to apply here (at least with repricing).

And yet, these repricers openly advertise that their products seek to “avoid price wars” and “look to raise prices 24/7” after their client seller acquires the Buy Box, which one would expect they could only obtain if they were the lowest price offer and would immediately lose upon raising the price.

Not quite. As BQool advertises, its algorithm (in the third bin pictured below) “matches the Buy Box price then increases the price to capture greater profits.”

Hold on, you say. If you raise the price after you get the Buy Box, would you not lose it immediately to a lower priced seller? After all, that’s how competitive markets work—a given seller is a price taker not a price setter, and any attempt to raise the price would result in losing sales to rivals.

Not in this case. Repricers can adopt similar strategies (e.g., “avoid price wars” and “raise prices at every opportunity,” including setting similar floor prices, ignoring each other’s pricing, slowing reaction time (a time delay), and “match but do not undercut.” In other words, repricing algorithms can tacitly collude without any explicit coordination by mutually recognizing each other’s strategy, a process known as “cross-platform recognition.” For example, observing that a seller alters its price every 15 minutes would suggest the use of a repricer.

Simply put, the issue isn’t so much that sellers on Amazon use a common pricing algorithm (though many sellers use one or more repricers), but rather that they use repricers that adopt common strategies based on a common knowledge structure, without directly coordinating. This reflects industry-wide algorithmic standardization. If algorithms settle on a common standard, collusive outcomes can occur even if no obvious rim to an alleged “hub-and-spoke” conspiracy exists. A bevy of research, which I review and describe in my paper, has already observed the same collusive outcomes with Q-learning algorithms (a type of algorithm that falls under reinforcement learning).

Focusing solely on common algorithms can create a tunnel vision that misses other conditions in which algorithmic pricing can harm competition and raise prices. Building a modern-day Maginot Line against the use of common algorithms may accomplish little to defend competition if sellers can outflank it through industry-wide algorithmic standardization.

How tacit coordination occurs

But wait, you say, if Seller A holds the Buy Box, wouldn’t Seller B still have some incentive to undercut Seller A’s price to secure the Buy Box for itself? Otherwise, how does the Buy Box change hands?

This is where the coordination that Amazon’s Buy Box rotation algorithm effectuates comes into play. With rotation, Amazon gives the Buy Box to one seller for a period of time, say two hours, then rotates to another similar seller for the next two hours and so on. Rotation allows sellers (even at slightly different prices) to adopt a “wait my turn” strategy and share the Buy Box rather than aggressively competing for it. The seller holding the Buy Box knows when it can profitably raise the price incrementally without being undercut, and the other sellers that use repricing algorithms have little incentive to undercut the price because they will get their turn to sell at the same higher price.

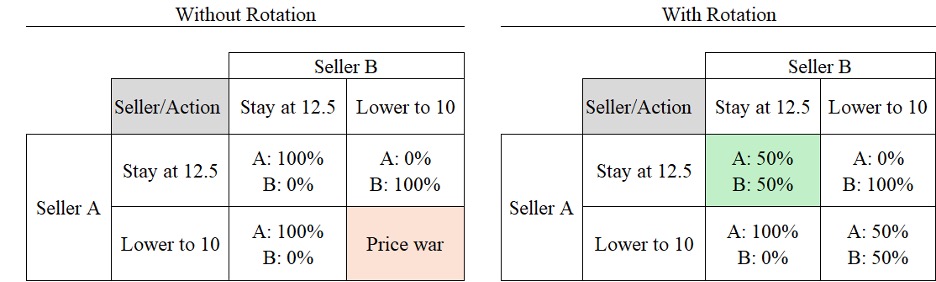

Basic game theory can illustrate the payoff scenarios here. Suppose Seller A has the Buy Box and prices at $12.50. Without rotation, Seller B cannot simply match, it must undercut to get the Buy Box. This will prompt A to respond in turn by undercutting B, resulting in a price war (the bottom right box in the “Without Rotation” scenario). This is the sort of aggressive price competition that would benefit consumers.

With rotation added, however, the incentives change. Seller B knows that by matching A at $12.50, it will eventually get its share of time with the Buy Box. So B doesn’t undercut A, and the price stabilizes at $12.50 (upper left box in the “With Rotation” scenario”). So, both Sellers A and B have the incentive to explore upward, not downward pricing scenarios.

Repricers themselves say as much, advertising that they look to raise prices 24/7. Here’s Flashpricer saying exactly this.

And here’s Sellersnap echoing it.

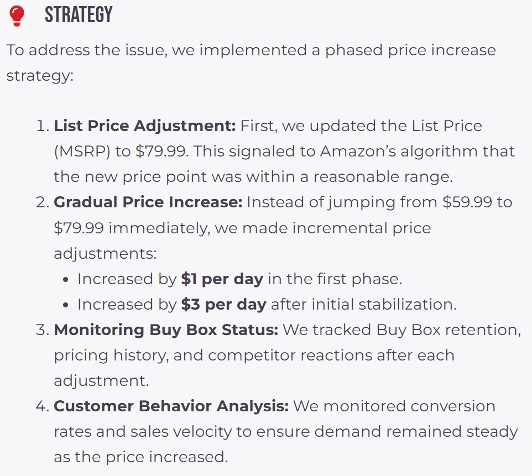

And here’s a case study from marketing agency BellaVix, titled “Successfully raising price while retaining the Buy Box,” that discusses how “A premium skincare brand selling on Amazon faced challenges when attempting to raise the price of their best-selling Crepe Repair Cream from $59.99 to $79.99” (a 33 percent price increase!).

And here’s how BellaVix describe its strategy to overcome those challenges and successfully raise the price to $79.99.

Note that BellaVix first changed the list price, which provides an anchoring effect, not only for consumers but also for Amazon’s algorithm. This move also exploits information asymmetries between the seller and buyers, well discussed in the literature. Such asymmetries result in a market failure, where the price no longer reflects the true market value of the product. Then, BellaVix gradually raised the price, exactly the process that rotation enables and that repricers openly advertise.

In my paper, I discuss the concepts of information asymmetries and anchoring and the latter’s effects on accepting or rejecting price recommendations from algorithms. Perhaps rather shockingly, BellaVix successfully raised the price by 33 percent without losing the Buy Box entirely (though the Buy Box likely rotated), offering a practical example of the strategy I described above.

But, you say, a shopper can just switch to Walmart to avoid the repricers. Sorry, repricers such as Flashpricer, which advertises “AI-powered algorithms for every competition scenario and business model that look for opportunities to raise prices 24/7,” as well as Streetpricer, which “Checks if we still hold the BuyBox after each price increase – backtrack if necessary” are there as well. In fact, repricers are ubiquitous across various platforms, such as Airbnb, Vrbo (e.g., PriceLabs) and others, not just e-commerce.

Bad AI risks driving out the good

Nothing discussed above means that prices always rise. Nor do they need to do so for anticompetitive harm to occur. Remember, the benchmark isn’t whether prices go up or down in the absolute sense, but rather relative to the competitive benchmark. Prices may fall in the absolute sense if, for example, a new entrant unfamiliar with the tacit agreement qualifies for the Buy Box and begins exerting some pricing discipline. Moreover, just because competition occurs in some cases on Amazon does not offset the anticompetitive conduct or render it trivial. After all, not everyone gets lung cancer after smoking, but we still warn against its dangers.

Of course, firms employ algorithms for various beneficial uses, such as identifying fraudulent sellers or counterfeit products. As such, anticompetitive uses of pricing algorithms has another harmful effect—nefarious uses of artificial intelligence can drive out the beneficial ones, an outcome known as Gresham’s Law that occurs through adverse selection.

Much of the problem here results from information asymmetries, both between sellers and buyers and between regulators and algorithmic pricing providers and the platforms on which they occur. Many machine learning algorithms that power AI are “black boxes,” such as neural networks, ensemble models like boosting, random forests, and so on. Having a rudimentary understanding of such algorithms goes a long way toward protecting against anticompetitive consequences they might cause.

Moreover, as this article shows and my paper discusses in some length, harm to competition can occur even using simple rules-based pricing algorithms from independent providers and even in the absence of sharing competitively sensitive information. The old Latin saying caveat emptor (buyer beware) has perhaps never been more poignant than in this dawning age of algorithmic pricing.

Common pricing algorithms can be used to coordinate prices among sellers, to the detriment of buyers. RealPage is the seminal case, but there are (alas) plenty of others. The problem is particularly acute in a two-sided transactional platform setting, where the platform influences—and sometimes coerces—the pricing decisions of its sellers.

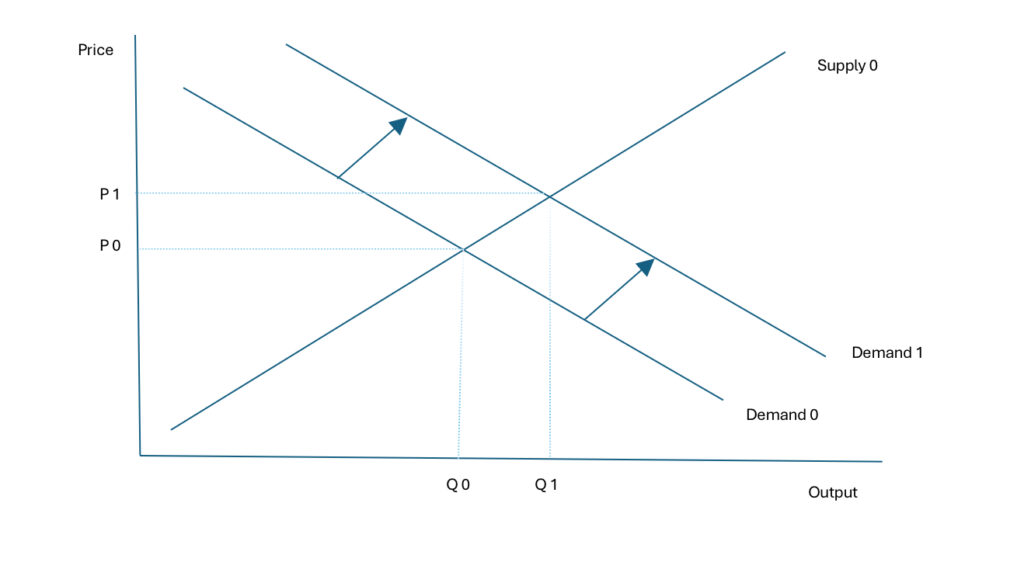

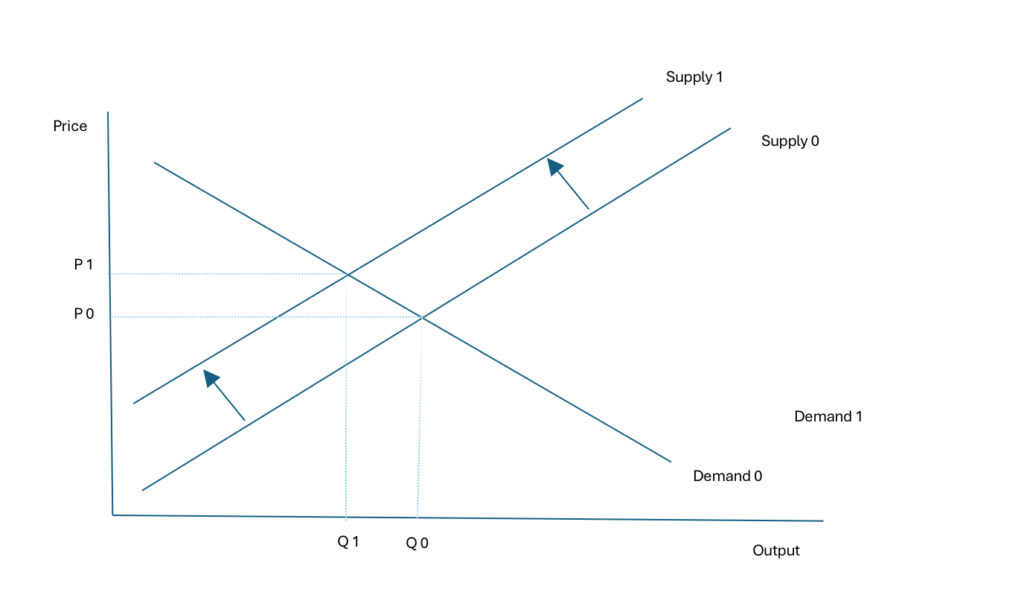

Take the case of Airbnb. Even before considering its “Smart Pricing” tool aka common pricing algorithm (discussed below), Airbnb inflicts tremendous costs on society. The short-term rental platform keeps rents artificially high by converting capacity for long-term (e.g., monthly or annual) rentals into short-term (e.g., daily) rentals. When the supply of long-term rentals artificially contracts, holding demand for apartments fixed, rents zoom upwards.

And high rents keep residents from spending money on other things—a drag on economic activity—and even contribute to homelessness for those who are priced out of the rental market entirely. According to a study by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, a record 12.1 million Americans in 2024 were spending at least half of their incomes on rent and utilities, putting them at increased risk of eviction and homelessness.

Economists have studied the inflationary impact of Airbnb on rents. Calder-Wang (2021) found that the presence of Airbnb in New York leads to a transfer from renters to property owners of $200 million per year or $2.7 billion in net present value. Barron, Kung and Prospero (2017) found that a one percent increase in Airbnb listings leads to a 0.018 percent increase in rents; in aggregate, the growth in home-sharing through Airbnb contributes to about one-fifth of the average annual increase in U.S. rents. Seiler, Siebert, and Yang (2022) found that Irvine’s short-term rental ban reduced contract rental prices in the long-term rental market by 2.7 percent between 2018 and 2021. (Airbnb consultants point to evidence that Airbnb puts downward pressure on hotel prices for travelers, but absent some redistribution mechanism, that purported benefit to out-of-towners cannot offset the harms to local residents from higher rents.)

To bring down rents, Barcelona recently moved to end licenses for Airbnb homes, requiring owners by 2028 to offer them as long-term lodging at capped rents or put them up for sale. Closer to home, since September 2023, New York imposed a requirement that hosts must be present for stays under 30 days, and limited guests to two, reducing available listings on Airbnb. Similarly, in Santa Monica, the host must be present during the guest’s stay and unhosted rentals are banned, and Las Vegas bans non-owner-occupied short-term rentals. New Orleans banned Airbnb rentals in the French Quarter.

Airbnb’s “Smart Pricing” tool

Converting housing into short-term rentals is not, on its own, a cognizable violation of the antitrust laws, notwithstanding the clear price and output effects. What is cognizable, however, is price fixing, or the coordination of pricing strategies and output between horizontal rivals. Here the horizontal rivals are homesharers in the same geographic market. And while evidence of an illegal agreement to fix prices is typically challenging to detect—after all, minimally savvy competitors are unlikely to leave breadcrumbs that trace back to illegal behavior—Airbnb has at least invited homesharers on its platform to participate in one such conspiracy.

Here’s how: Airbnb offers homesharers on its platform a tool called “Smart Pricing,” which is an internal pricing algorithm that automatically updates homesharers’ listing prices. Hosts can opt in to Smart Pricing and set certain parameters, including minimum and maximum prices, then Smart Pricing does the rest by pinning prices to the “competitive” price. Of course, “competitive” is a misnomer to the extent prices are no longer a function of independent price setting among homesharers, but instead an automated prediction by the algorithm of what the market will bear.

The primary harm from Airbnb’s Smart Pricing tool is inflated rents that flow from a price-fixing conspiracy. Airbnb’s Smart Pricing tool also raises concerns regarding price discrimination, as it not only considers the features of the property and economic conditions, but also the characteristics of the guests themselves—for example, Airbnb acknowledges that Smart Pricing considers guest behavior in its algorithm. While maximizing the quality of the guest experience is a worthy goal, exploiting information asymmetries to extract supra-competitive prices can evince a market failure. Alas, the antitrust laws generally condone price discrimination. (For a great example of price discrimination achieved via algorithm aka “surveillance pricing,” check out Groundwork’s recent study of Instacart, another online platform that sets prices for sellers such as Target and Safeway.)

While Smart Pricing offers homesharers a convenient tool for managing their prices, Airbnb’s interests may not be aligned with the interests of homesharers. Some hosts have expressed frustration at the Smart Pricing algorithm for automatically pinning prices to the high end of their price range. Other hosts have complained that applying additional “rule sets” to their properties kicks them out of the Smart Pricing tool, creating friction for hosts who otherwise prefer to automate their prices. In other words, Airbnb’s Smart Pricing tool betrays a conflict of interest, and what’s good for the platform may not be, in the end, what’s good for individual homesharers. Insight into where precisely a listing will be ranked is limited because Airbnb’s recommendation algorithm is private. For example, the algorithm might punish non-adopters of the Smart Pricing tool by lowering their placing on the results page.

Airbnb incentivizes use of its Smart Pricing tool by telling homesharers that setting a “competitive” price helps improve a property’s ranking in search results. And the easiest way to set a “competitive” price without “constantly monitoring it”? Well, by using Airbnb’s Smart Pricing tool, of course. Want to automatically change your price in response to “travel trends” in your area? Turn on Smart Pricing. Although Airbnb offers that homesharers can override Smart Pricing at any time, some hosts have expressed frustration at the inability to apply additional “rule sets” without being kicked out of Smart Pricing.

Even when a homesharer declines Smart Pricing and elects to use its own pricing algorithm, doing so does not extinguish the concern of inflated prices. The economics literature recognizes how independent algorithms can learn to collude with each other by avoiding price wars. Moreover, the mere existence of a default option establishes a price floor around which all other prices are established.

If not dispositive of an illegal price fixing scheme, these facts provide at least circumstantial evidence that Airbnb is coercing homesharers into adoption of its price coordination tool, including by withholding access to consumers through search page rankings. If so, both Airbnb and participating homesharers may be on the hook.

An unwelcoming legal environment

Companies across a large swath of industries, from meat processing to hotels to real estate, are increasingly using common algorithms to set prices—and facing federal enforcement actions for doing so. Despite a defendant-friendly legal terrain, many of these arrangements have been challenged by either private or public enforcers. In large part, these cases focus on the exchange of competitively sensitive, often non-public, information between competitors, from which courts have begun to infer the existence of an illegal agreement. Self-styled “revenue management” or price- and rate-setting services like RealPage or Yardi in the rental housing industry, Cendyn in the hospitality industry, or Agri Stats in the poultry processing industry, have in recent years defended themselves against protracted litigation alleging their facilitation of these information exchanges. (Disclosure: I served as the economic expert for plaintiffs in two Agri Stats cases.)

That the DOJ recently settled its litigation with RealPage on decisively unfavorable terms suggests an unfriendly legal terrain. (Alternatively, it could reveal the subversion of law enforcement by a politicized agency.) And if there was any doubt about the steep evidentiary hurdles faced by plaintiffs, one needs only look at a strange and economics-free decision in the Ninth Circuit.

The Ninth Circuit’s decision in Gibson v. Cendyn reveals a basic misunderstanding of the economics of pricing. To dismiss any vertical relationship between Cendyn and its hotel clients, the Court claimed that “While hotels may use Cendyn’s revenue-management software to maximize profits, the software is not an input that goes into the production of hotel rooms for rentals.” (emphasis added) Yet the revenue-management software is precisely an input in the selling of hotel rooms, the output that forms the relevant product market (not producing or constructing hotel rooms from scratch). While hotels could technically function without it, the common pricing tool improves a hotel’s ability to extract additional surplus from their guests in the sale of the relevant product (again, not constructing hotel rooms).

The Cendyn decision also asks, “Why don’t the independent choices of Hotel Defendants to obtain pricing advice from the same company harm competition, as alleged here? Because here, obtaining information from the same source does not reduce the incentive to compete.” Yet the entire purpose of a common pricing algorithm is to reduce the incentive to compete unilaterally. If firm A knows that its rival, Firm B, is going to default to the joint profit-maximizing price as determined by the common pricing algorithm, it is in Firm A’s interest to mimic that price and not undercut it. In this sense, the algorithm facilitates a coordinated monopoly outcome that would not be as easily achievable in its absence. And for many common pricing algorithms, the clients are further incentivized to accept the recommended pricing for fear of being disappeared in search results.

The Cendyn decision also identified the sharing of competitively sensitive information as a key ingredient that enables collusion. This is also wrong as a matter of economics. Turning over one’s pricing authority to a common agent—whether a dude named Bob or an AI-based algorithm—increases the chances of reaching the monopoly price relative to a world in which companies make independent pricing decisions. This is true even when information about a rival’s costs or capacity is commonly known. Can firms in an oligopoly setting with complete information feel their way to the monopoly price in a repeated setting? Perhaps. But at least with independent pricing, there’s a chance that your rival will undercut your inflated price to gain share. And that threat tempers one’s enthusiasm to raise prices. Once rivals agree to turn over pricing to a common agent, however, that threat is extinguished. (This is not to say that sharing of confidential information isn’t a viable pathway to a finding of liability. It just shouldn’t be a necessary condition. In any event, homesharers are likely sharing confidential information with Airbnb, including the number of days for which the seller plans to occupy her home.)

That’s enough of the economics. For a nice explainer on the legal flaws in the panel’s decision, check out this brief by the American Antitrust Institute (AAI), urging the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals to grant rehearing en banc. By insisting on a causal link between the licensing agreements and a restraint in the relevant market, AAI’s brief explains, the panel confused proof of an agreement with proof of the agreement’s anticompetitive effects. The brief also explains how the decision conflicts with Board of Trade of the City of Chicago v. United States, 246 U.S. 231 (1918), by creating a new category of agreements not subject to rule-of-reason analysis.

The case against Airbnb

Common pricing algorithms, like Airbnb’s Smart Pricing tool, can erode the fair functioning of markets when they deprive competitors of their independent decision-making authority. In a well-functioning competitive market, a series of (ideally, atomistic) suppliers would set their price independently. But when sellers can coordinate their prices, it is easier to move from a competitive output to something that approximates the monopoly outcome. Despite the propensity for market distortion, enforcing the antitrust laws against common pricing algorithms may prove challenging absent additional circumstantial evidence of an acceptance of that invitation to collude.

Airbnb’s facilitation of pricing decision among horizontal competitors should be assessed under the per se standard, which eliminates any consideration of efficiencies and obviates the need to establish market power. If assessed under the more burdensome rule-of-reason standard, plaintiffs would have to establish that Airbnb has market power, either directly, via evidence that it has the power to raise prices over competitive levels, or indirectly, via evidence that it commands a high share of a relevant product market. Empirical evidence that Airbnb’s smart pricing algorithm has led to higher short-term rents on the platform would suffice for direct proof. Regarding indirect proof of Airbnb’s power, per one estimate, Airbnb commands 43 percent of the U.S. market for online travel agents (aka short-term rentals), with Vrbo and Booking.com occupying significantly smaller shares. This estimate includes “direct bookings” in the relevant market, however, which arguably do not provide the same services as Airbnb and thus could plausibly be removed from the market, resulting in an even higher Airbnb share.

Airbnb isn’t just facilitating a data exchange; it is incentivizing or coercing homesharers on its platform to participate in a common pricing scheme. A coercion-based approach to enforcement should obviate the need to provide heightened evidence of acceptance, because participation in the scheme is a condition of a participation on the platform. Platforms wielding access to non-price business services, like advertising or market research services, on the condition that sellers accept price recommendations deprives sellers of their independent pricing authority. Airbnb’s “Smart Pricing” tool coerces their participation in a price-fixing cartel. With luck, the authorities are watching.

On November 18, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) lost its landmark case against Meta over its acquisition of Instagram. The opinion was issued by Judge James Boasberg. The FTC spokesperson commented to the press decrying the loss as is usual agency practice. But the whole statement was far from usual. FTC spokesperson Joe Simonson told the press: “We are deeply disappointed in this decision. The deck was always stacked against us with Judge Boasberg, who is currently facing articles of impeachment. We are reviewing all our options.” This attack on Judge Boasberg aligns the FTC’s leadership with the partisan attacks on Judge Boasberg emanating from the Trump administration and its supporters.

I will not focus on the substance of the Meta case—Tim Wu has treated that subject well in the New York Times and on The Sling’s podcast. Instead, I would like to focus on how the FTC has chosen to describe Judge Boasberg and the destructive impacts that choice could have on the FTC.

To my knowledge, the FTC has never issued a statement like this impugning a federal judge’s neutrality. Doing so when there is no evidence of such a bias would always be reprehensible. But to make such a claim against Judge Boasberg is particularly counter-productive.

The FTC does not even attempt to suggest why Judge Boasberg would be biased against the agency in its statement. That is likely because the FTC’s leadership believes no such thing and is merely joining the right-wing criticism of Judge Boasberg for ruling against the administration. Because there is no substance to these allegations, I will concentrate on why attacking Judge Boasberg is counter-productive.

Judge Boasberg has served as a judge on the District Court for the District of Columbia, known as DDC for short, since 2011 and has served as Chief Judge of the district since 2023. He is one of the most highly respected district judges in the United States. Moreover, as chief judge, he is responsible for the administering DDC’s operations. He also represents his colleagues on DDC at the Judicial Conference, the policymaking body of the federal courts. In the past five years alone, he has been the assigned judge in four FTC antitrust cases according to Westlaw.

But more important than anything about Judge Boasberg specifically, DDC is the most important district court to the FTC. As the FTC’s home district court, the agency litigates in DDC more often than any other district. This year, the FTC has six cases in DDC. In the last five years, the agency has had 37 cases before the court. The other judges on this court are almost certainly paying attention to the insults the FTC chose to bestow on their colleague and chief judge.

This childish statement by the FTC therefore jeopardizes not only the agency’s credibility in front of a prominent district judge but also its credibility with the most important district court to the agency.

But it is not FTC leadership that will pay the price for this choice. The career attorneys who must litigate these cases will have their hard work put on the line because Chair Ferguson wanted to score political points with President Trump.

The FTC has a deep store of credibility with the bench. FTC attorneys are careful, professional, and deliberate in how they litigate cases. But credibility is easy to burn and hard to earn. And with each unprofessional, craven political stunt Chair Ferguson pulls with the FTC—from investigating Elon Musk’s political opponents to threatening Google over allegedly “partisan” email filtering to this attack on Judge Boasberg—Chair Ferguson burns the FTC’s credibility. Regardless of one’s views of Judge Boasberg’s Meta ruling, antimonopoly advocates should denounce this statement by the FTC.

Bryce Tuttle is a student at Stanford Law School. He previously worked in the office of FTC Commissioner Bedoya and in the Bureau of Competition.

Home affordability is a pressing issue. Young people often enter the workforce saddled with student debt, limited work options, and faced with exorbitant housing costs. For the millennial generation, the prospect of buying even a “starter home,” an option available to previous generations, has all but disappeared in most urban and suburban areas. The affordability problem touches more than just youth—blue collar workers, the foundation of this country without whose labor the economy would grind to a halt, fact made obvious during the early days of the COVID pandemic, no longer have the same opportunities either.

Efforts to address such an affordability crisis by exploring the viability of various options are a worthy endeavor, to be sure. But, as the intrepid detective of Hollywood fame, Jack Reacher, reminds us, “in an investigation, details matter.” The latest potential solution, which President Donald Trump proposed via social media on November 7, contemplates offering 50-year mortgages, up from 30 years—that is, increasing the time horizon for mortgages by two-thirds. Presumably, the logic motivating this argument posits that spreading out the mortgage over a longer horizon will lower monthly payments, increasing affordability.

Offering 50-year mortgages will do no such thing.

To repeat, the goal of making home ownership more affordable is laudable. But offering 50-year mortgages does not make ownership more affordable. At best, it makes mortgages more affordable. This policy preys on an unfortunate consumer tendency to buy a monthly payment rather than buying the property itself (a home or a car).

Most people who have shopped for a car will have likely received the question, “What sort of monthly payment would you like to have?” If you’re shopping for anything that requires a loan, and you get this question, stop right there.

You are not buying a monthly payment. This question conflates two products: the property (e.g., home or car) and the loan. The monthly payment just combines the two, masking the price you end up paying for the product you wanted in the first place. Sure, you might be able to get a lower recurring payment, but at what cost? Knowing the answer can inform the difference between a good and a potentially catastrophic financial decision.

The End of the Dream?

The American Dream, whatever vestiges of it remain, has always been about owning one’s home, not owning a monthly payment on a mortgage. Extending the payment over a longer period not only does not advance that goal, it actively undermines it; the longer the loan period, the smaller the proportion of each payment that goes to principal. This just means that you end up paying a higher price for the home. The longer payment schedule merely allows you to spread out the payment over a longer period in exchange. But that costs money, so let’s look at some numbers.

Suppose you want to buy a $500,000 home. Assuming you have the 20 percent to put down (congrats!), you will have a $400,000 mortgage. Your monthly mortgage payments will just depend on the interest rate you obtain and the term of the loan (usually 15 or more commonly, 30 years). Calculating the monthly payment, ignoring for the moment closing costs, home insurance, and other associated costs that one pays through escrow, is a simple calculation that one can do in Excel, either by hand or using the built-in payment (“PMT”) formula. The table below shows the calculations if you choose a 15- or 30-year mortgage. Note that a 15-year mortgage also commands a substantially lower rate (currently about 5.6%) compared to a 30-year mortgage (currently about 6.4%), because the 15-year mortgage carries lower risk.

Table 1: 15 vs. 30-year Mortgages

| Home Price | $500,000 | $500,000 |

| Loan Amount | $400,000 | $400,000 |

| Interest Rate | 5.6% | 6.4% |

| Loan Term (Years) | 15 | 30 |

| Monthly Payment | $3,290 | $2,502 |

| Total Amount Paid | $592,128 | $900,729 |

| Total Interest Paid | $192,128 | $500,729 |

With a 15-year mortgage, you face a higher monthly payment, but you end up paying less than half of the amount in interest. Assuming you pay off the 30-year mortgage at the end of the term, you will end up paying more in interest (about $500k) than the $400k you originally borrowed!

Now, let’s see what happens with a 50-year mortgage. The table below has the same two scenarios as above (Options 1 and 2, respectively), and two additional 50-year mortgage scenarios: (1) with the same interest as a 30-year mortgage, and (2) with the more likely increased mortgage of 7.3%. The increase in the rate associated with a 50-year mortgage would occur for the same reason that 30-year mortgages command higher rates than 15-year ones (higher risk).

Table 2: 15, 30 and 50-year Mortgages

Let’s look at Option 3, assuming the same 6.4% rate for 30- and 50-year mortgages. Yes, the monthly payment on the latter drops by $277 per month, from $2,502 to $2,225. Ok, you say, this is nice. But is it more affordable? Look at the cost of that lower monthly payment: over the 50-year length of the mortgage, you end up paying over $934k in interest to borrow $400k—that is, nearly a million dollars in interest alone!

But wait, it gets worse.

The mortgage rate will likely increase by raising the term from 30 to 50 years. Let’s say the 50-year rate is 7.3%. Then, not only are you paying the same monthly payment ($2,502, Option 2 vs. Option 4), but you’re also paying $1.1 million in interest alone with Option 4. You’re now paying more than double in interest while not even getting a lower mortgage payment. Guess who benefits here? (Hint, it’s not you.)

Adding Insult to Injury

Of course, you’re unlikely to carry the mortgage to term. This is where familiarity with the amortization chart helps. The average amount of time people hold a particular loan before moving or refinancing is 12 years. We can re-calculate the total amounts paid in interest and principal using that term. Keep in mind that earlier in the mortgage term, the majority of your payment usually goes to interest not principal. So, you’re not really gaining much equity.

Here’s where things go from worse to terrible.

Table 3: 15, 30 and 50-year Mortgages with 12-year Amortization

Look closely at how much of your principal you’ve paid off under these scenarios. With a 15-year mortgage, you’ve paid off just under 75% of your total mortgage of $400k (equal to $291k divided by $400k). With a 30-year term, you’ve paid off less than a quarter (equal to $79k divided by $400k). Now the terrible part: with a 50-year mortgage at the same rate as a 30-year mortgage, you’ve paid off less than $20k in principal in 12 years. In other words, even though you will have made a total of $320,371 in mortgage payments over that period, $300,631 of that will have gone to pay off interest and only $19,740 went to principal. You’ve gained less than $20k in equity from your payments. With the more realistic higher rate on a 50-year mortgage, you end up paying just $15k in principal. In other words, maybe, just maybe, you end up paying off the equivalent of your closing costs.

Ostensibly, this idea was intended to at least superficially appeal to the younger generation aiming to salvage some scraps of the dream of homeownership. Younger people tend to hold mortgages for shorter periods: as they build families they seek out more the requisite spaces. On that note, let’s look at the amortization schedule after holding the mortgage for five years.

Table 4: Five-Year Amortization Schedule

By taking a 50-year mortgage, you end up paying between $133k (Option 3) and $150k (Option 4), but only between $6,447 and $4,722 goes to principal! Over 95% of your payment has gone to interest. Again, you’ll walk away with next to nothing after the sale.

Let me emphasize. As Option 4 shows above, after paying your 50-year mortgage for a full five years, you will have managed to pay down the principal on our loan by less than five thousand dollars, even though you paid a total of over $150k towards your mortgage. You’re not really becoming a homeowner, you’re financing someone else’s investment vehicle.

When you buy a home, you generally hope to gain equity. This comes (1) from the portion of your mortgage payment that goes to principal vs. interest and (2) market factors. As the amortization schedules above show, the longer the term of your mortgage, the lower the percentage of your payment that applies to principal. That means you’re left open to the vagaries of the property market. You can actively improve the home in the hope to achieve a positive return on investment, but money that you could have used to do so now goes to paying down interest.

This might be the time you expect to hear that there’s a silver lining somewhere. No. Just more clouds.

Remember, because of the transaction costs involved, once you buy a property, you’re very likely immediately underwater. You’ve likely paid some closing costs to get into the mortgage. And if you changed your mind and wanted to sell the property immediately and hire an agent, you will end up paying around 3-6% of the total sales proceeds. Assuming you could sell the home for exactly the price you paid, $500k, that means you’re $15k-$30k underwater, plus the title costs.

Let’s look again at Option 4 in Table 3. After 12 years, you’ve paid $345k in interest but only paid off $15k in principal, just barely enough to cover a 3 percent agent fee. Not only that, the $100k you’ve put as down payment has done nothing over this time, unless the home prices have increased. The 50-year mortgage option just creates more mortgage-backed investment vehicles, not more homeowners.

Better Options Than 50-Year Mortgages Exist

I’ve skipped over some additional details, all of which tend to make this calculation even worse for potential homeowners. Of course, there are downstream effects as well. Locking people down in debt restricts their mobility, with second-order effects on labor markets. Suffice it to say, even if this idea were well-intentioned, it should be dismissed immediately. I would expect even the Abundance crowd to concur, as 50-year mortgages would counteract attempts to increase home supply. Yes, maybe we’d see more mortgages, but not more homeowners. And isn’t greater home ownership what the American Dream was supposedly about?

So what’s the solution? Lowering rates would help. Most homeowners with mortgages have rates below 5% and are unwilling to forego them without compensation. I hear the common argument that “well interest rates were much higher in the 1980s.” This misses the point. The issue isn’t as much with the size of the interest rate as with the rapid change in rates from less than 3% to north of 6%. People have locked in at lower rates, and now they’re wearing “golden handcuffs”. For example, financing a $400k loan at 3% means a $1,686 monthly payment. Increasing the rate to 6.25% raises the monthly payment by nearly $800 to $2,463. But not only have interest rates risen, so have home prices. So, instead of a $400k loan, maybe you now have to take out a $500k loan to buy the same or similar house. That means a $3,079 monthly payment. So, you can see that the same house now requires precariously close to double the monthly payment in this case. Even if people want to move, they stay put. This means a lot of shadow inventory is sitting out there, and lowering interest rates would go a long way to inducing it to come on the market.

When it is funded, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP (colloquially known as food stamps) helps feed over 40 million people every month by dispensing $187 per average recipient. The program is especially critical for families—children represent about 40 percent of all SNAP recipients. Despite 78 percent of Americans (and 69 percent of Republicans) holding a positive view of SNAP, one of the many detrimental consequences of the longest government shutdown in U.S. history is that the program’s funding is about to dry up.

In anticipation of extraordinary conditions, such as a long-lasting shutdown, Congress had set aside a small “contingency reserve” of funds to be used “at such times as may become necessary to carry out [SNAP] operations[.]” Breaking from the USDA’s September 30 interpretation of this language, on October 24, the Trump Administration claimed it could not legally tap these funds during a shutdown—threatening to disburse no benefits in November. This novel understanding of the law (a continuation of the Administration’s hostility to a program from which it has already cut $187 billion over the next decade) was quickly rejected by the courts in a pair of Halloween rulings mandating that the Administration use these funds. In the midst of this court battle, the president waffled between the position that “If we are given the appropriate legal direction by the Court, it will BE MY HONOR to provide the funding” (October 31 post), and that SNAP “will be given only when those Radical Left Democrats open up the government, which they can easily do, and not before!” (November 4 post).

After the president’s hemming and hawing, the Administration set forth a plan to offer partial payments to SNAP recipients for November. Originally, payments were anticipated to be half of full benefits, but because math is hard for merit-based hires, this number has since inexplicably increased to 65 percent of full benefits. U.S. District Judge John McConnell has deemed these partial payment plans insufficient. SNAP advocates argue that the partial payments would only create bureaucratic bottlenecks that would slow access to these critical funds. Of course, the Administration appealed this “absurd” ruling, which would ensure the wealthiest country in the world allows its poorest denizens to afford food. For now, the Supreme Court has paused Judge McConnell’s full payment order as it awaits a decision from the First Circuit Court of Appeals. This pause occurred only after at least some states disbursed full SNAP payments to recipients, and, amid a deluge of conflicting orders, the USDA seems to want states to magically claw back these full benefit down to its previous 65 percent partial payment plan.

Treating SNAP and Non-SNAP Recipients “Equally”

Amid plans to provide only partial SNAP benefits, many grocers were intending to offer discounts to SNAP recipients to ensure their quantity of food consumed was minimally interrupted (and to avoid missing out on loss sales). For example, the McMinnville Grocery Outlets of Oregon tried to offer a 10 percent discount to all SNAP recipients whose food-assistance money had been frozen. Despite its court loss over halting payments completely, the Administration continues to selectively enforce policies to ensure some discomfort for those in need, including its own supporters. Hence, the USDA has warned grocers that these discounts, absent a waiver, run afoul of a rule requiring SNAP recipients to be treated “equally” compared to non-SNAP recipients. In response to that warning, many grocers ended their proposed discounts, though others retailers, like Instacart, continued to offer their planned discounts to SNAP recipients thanks to already having the needed USDA waiver.

Unfortunately, SNAP’s Equal Protection Rule (7 CFR 278.2(b)) does forbid “special treatment in any way” for SNAP recipients. The Biden Administration-era USDA also interpreted this to “prohibit[] both negative treatment (such as discriminatory practices) as well as preferential treatment (such as incentive programs).” The waivers that allow a small number of retailers (mostly farmers market) to offer discounts was codified in the 2018 Farm Bill (7 USC 2018(j)) to promote the consumption of healthier food. Ignoring the fact that such non-discrimination rules were premised on full-funding and delivery of SNAP benefits, the Administration can plausibly argue that its hands are tied.

As we have seen so frequently with this Administration, however, the Executive Branch has significant latitude in whether and how it will actually enforce statues and regulations. For instance, this decision stands in direct contrast to this same Administration’s abandonment of the antitrust case against PepsiCo under the Robinson-Patman Act; apparently, a supplier’s selective use of discounts to large stores does not warrant similar condemnation to grocers offering discounts to those in need. We would be remiss not to mention that PepsiCo donated half a million dollars to Trump’s inauguration ceremony, after a brief interlude of pausing political donations in the wake of the January 6, 2021 storming of the Capitol.

If anything is justifiably worth similarly lax enforcement, it would be the allowance of private discounts after SNAP recipients have faced an unexpected decline in governmental assistance. Hence, in our estimation, forbidding price discrimination in the name of equality—when such discrimination would assist impoverished people in a time of need—suggests that serving the poor does not rank too high in the Administration’s policy preferences. That the Administration has ignored price discrimination in other contexts, such as by airlines (when your trip is for business) or Uber (when your battery is low), reveals that Trump’s cruelty to the poor is likely the point.

Democrats have responded to the Administration’s enforcement of SNAP’s Equal Protection Rule with a bill—which does not appear to have Republican support—that would allow private discounts by grocers for SNAP recipients during government shutdowns. We think that Congress should push the boundary further, by amending the Equal Protection Rule to always allow discounts for SNAP recipients. Equality, while often laudable, is overrated here, as disparate conditions necessitate differential treatment.

To Limit Hunger, Allow Price Discrimination

So, what is price discrimination? And why should it be used to support SNAP recipients? In its simplest form, price discrimination is the ability for sellers to charge different prices to different buyers. Think of a discounted museum ticket to students or movie theaters offering cheaper matinees. Such common and innocuous pricing strategies might conflict with the layperson’s negative associations with the term discrimination; for instance, Merriam-Webster includes the word “unfairly” in its definition. Yet economists often use a definition that strips away this negative baggage. Under this conception of the word, SNAP discriminates on the basis of income—those below a certain income thresholds receive benefits and those above are deprived benefits.

Economists tend to support price discrimination because it can increase consumption and social welfare under certain conditions. Price discrimination necessarily benefits companies (otherwise they would never adopt it as a pricing strategy!) but also may benefit certain consumers, like SNAP recipients, with lower willingness to pay for (or lower ability to afford) goods. Under certain forms of price discrimination, these consumers can increased their quantity consumed thereby improving their welfare. Whether these benefits outweigh the potential increase in price to consumers with higher willingness to pay depends on the exact nature of the market and the form of price discrimination. For instance, one of us has a prior piece in The Sling explaining how perfect price discrimination (by airlines) in the face of quantity restrictions is undesirable.

Price discrimination is in theory infeasible in competitive markets because sellers in such markets are price takers (facing a flat demand curve) with no impact on market prices. In the real world, however, markets are rarely perfectly competitive, and firms often have a degree of market power (facing a downward-sloping demand curve) and can influence market price. For instance, the USDA has found that the market concentration (a measure related to the potential for market power) of grocers has increased over the last 30 years and is particularly problematic in rural communities. Indeed, the mere proposition of these discounts by certain grocers is suggestive that these sellers are already operating above marginal cost and possess some degree of market power. Regardless, if price discrimination is infeasible in the long term due to competitive forces, then a policy that allows for price discrimination would have no long term effect—SNAP and non-SNAP prices would inevitably converge.

If price discrimination is possible, allowing grocers to concurrently drop prices to SNAP recipients and raise prices to non-SNAP recipients, then there are difficult tradeoffs to consider: the welfare harm of higher prices for non-SNAP recipients may be greater than the welfare gained by SNAP recipients and grocers. (In the real world, however, there is a distinct possibility that grocers simply drop the price to SNAP recipients and leave the price to non-SNAP recipients the same, which greatly simplifies the welfare calculus. There is no lump-of-profit law in economics deeming that losses incurred on one group must be recouped on some other.)

The overall societal welfare effect of price discrimination by groups (or what economists call “third-degree” price discrimination) is not straightforward, but social welfare tends to increase when output increases. This can happen when price discrimination creates new markets that were otherwise unprofitable (e.g., in the long run, price discrimination may mean that certain food deserts will disappear because a grocer can enter the market). Output can also increase if the price cuts to SNAP recipients allow some SNAP recipients to obtain needed food when they otherwise could not.

Beyond the potential welfare effects from greater output noted above, there are several other reasons to believe that allowing discounts for SNAP recipients will be beneficial. First, because the cost of SNAP is likely borne mostly by non-SNAP recipients (through taxes on higher income individuals), the decrease prices paid by SNAP recipients may allow for SNAP itself to need less money to cover the dietary needs of beneficiaries; in effect, allowing non-SNAP recipients to have a slightly lower tax bill. Second, and more significantly, there are several externalities at play; to name one, hungry people are less productive workers, and hungry children perform worse in school and jeopardize their long-term productivity. One study found that for every $1 spent on food stamps for a child, $62 of value were generated over that child’s lifetime. Third, there are also non-economic (equity) reasons to support such discounts: Non-SNAP recipients may be willing to face higher costs so their neighbors can afford to eat. In other words, society cares more about lifting up the downtrodden than the relatively minor costs borne by the better off.

Turn the Spigot and Let the Discounts Flow?

Because the Trump Administration has already indicated its opposition to the American welfare system, its open hostility to SNAP does not come as a shock. Nevertheless, while its true motives are hard to decipher, the Administration’s stance against allowing private discounts for SNAP could be defended by certain economists (not us) by appealing to concerns about the risk of inflation for non-SNAP recipients. Such concern would be unwarranted, however, if grocers are offering private discounts merely to mitigate short run losses in the face of a government-induced demand shock. In such situation, there is a low risk of the concomitant increase in the price paid by non-SNAP recipients ever materializing.

Regardless of these arguments, it is our contention that the economics suggests that allowing private discounts for SNAP recipients is simply good policy. The enormous lift to each SNAP recipient (getting to eat) swamps the likely trivial costs to each non-SNAP recipient, who are in a better position to absorb such costs. As such, we would urge Congress to explore allowing grocers to offer SNAP recipients private discounts not just during shutdowns but also in times of continuing resolutions and the oh-so-rare actual fiscal year budgets.

Advocates of all stripes will pounce on a Nobel prize in economics to promote their particular policy agenda. They find a strand of the work by the winning economist, or a snippet from the Nobel committee, spin it into their narrative, and voila, their pet theory is proven right. Even a Nobel prize winner says so!

We should take such claims with a grain of salt.

I confess that the initial coverage of this year’s economics prize, awarded on Monday to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for their work on the drivers of innovation, left me a little empty, as I couldn’t see any crisp policy implications. At least not at first.

But then Aghion was quoted in the New York Times, noting that he was optimistic about the prospects of artificial intelligence (AI), yet still “favored policies that promoted competition and did not consolidate power to just a few winners.” In a longer version of the story, he said “there needed to be competition policy so that AI innovators would not stifle rivals.”

Sometimes we don’t need to decipher the hidden meaning of a complex economic article written decades ago, or even the Nobel committee’s summary of an economist’s contributions. Sometimes we can just defer to what the economist actually says. Aghion is literally telling us that we’d be better off as a society if AI were competitively supplied, compared to a scenario in which AI is provided by a small handful of firms with near-monopoly power.

To take one possible scenario, imagine a “hypothetical” monopolist in the general search market with its own proprietary AI tool. It’s true that independent AI tools might shake up the general search market, assuming each AI tool competed on a level playing field. But if said search monopolist can preference its own AI tool to answer its users’ general search queries, then its search monopoly could be artificially extended.

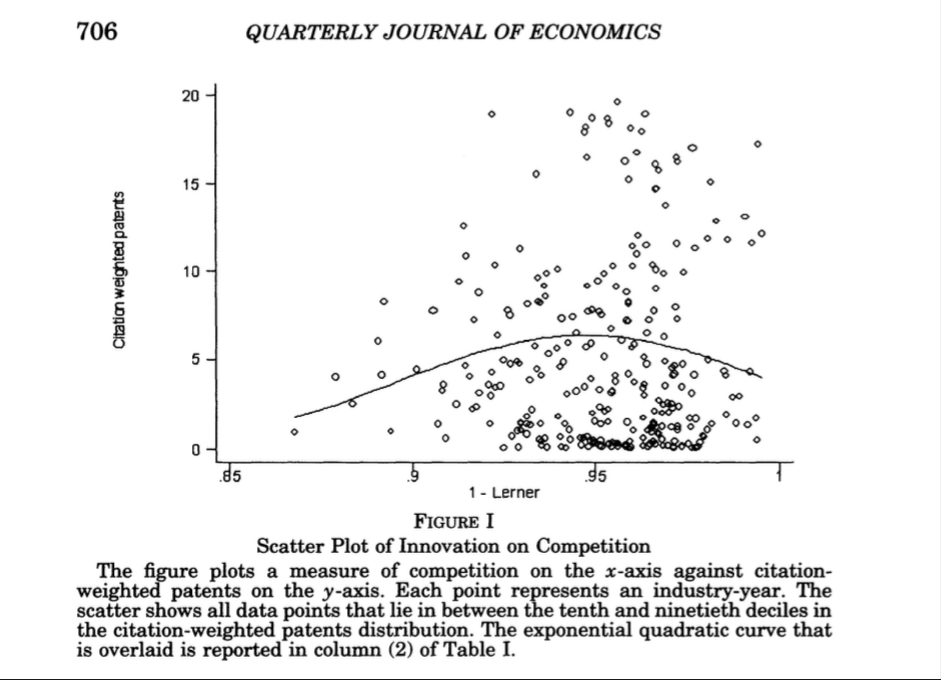

Indeed, Aghion’s and Howitt’s own research suggests that monopolists can be stifling for innovation. The figure below is reproduced from their 2005 Quarterly Journal of Economics article titled “Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship,”in which they studied the relationship between market power and innovation across UK industries.

The Y-axis plots the citation-weighted patents in an industry, a measure of innovation. The X-axis plots one minus the Lerner index or price-cost margin, a measure of competition in an industry. A value of one (far right along the X-axis) indicates perfect competition, as price equals marginal cost. Values below one indicate some degree of market power. As the figure shows, when industries become monopolized—one minus the Lerner index approaches zero—the amount of innovation decreases from its peak. In the words of the Nobel winners, “competition may increase the incremental profits from innovating, and thereby encourage R&D investments aimed at ‘escaping competition.’” The figure also indicates too much competition might be harmful for innovation as well.

The Pro-Monopolists Claim Victory

Despite this clear signal from one of the winners, the anti-anti-monopoly crowd, or more affectionately, the “pro-monopolists” as I like to call them, issued a press release trumpeting the exact opposite message—that this year’s Nobel prize stands for the proposition that antitrust enforcement is based on failed predicates and has swung too radically towards the interventionist side.

In a post titled “What Competition Scholars Should Know About the 2025 Economics Nobel,” ICLE’s chief economist Brian Albrecht argues that the work of Aghion and Howitt should cause a fundamental rethink on how we perform antitrust analysis:

The standard antitrust framework inherited from 1960s industrial organization focuses on market structure. Count the firms. Measure concentration. Assume that structure determines conduct, which determines performance. More firms mean more competition, which means lower prices and better outcomes. The U.S. Merger Guidelines embody this view with their use of Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) thresholds.

The Aghion-Howitt framework tells a different story. Competition is a process of innovation and displacement. Firms compete by trying to make better products, not just by cutting prices on existing ones. What matters is not the number of firms at any point in time, but whether new innovators can challenge incumbents. Market structure is an outcome of this competitive process, not just a cause of competitive behavior.

Notwithstanding Aghion’s own words calling for vigorous competition policy, Albrecht’s spin is a mischaracterization of how antitrust works in practice. Antitrust decisions don’t turn on simplistic concentration metrics in a market. In a single-firm monopolization case, concentration metrics are rarely used; when proving a defendant’s market power indirectly, what matters is the defendant’s share of the relevant market, along with evidence of of significant entry barriers. Alternatively, market power can be shown directly with evidence that the defendant raised prices over competitive levels or excluded rivals. But market power by itself doesn’t constitute a violation of antitrust law, as Albrecht intimates; plaintiffs must criticallyshow anticompetitive effects.

Even in merger cases, where concentration metrics play a role in establishing a presumption of anticompetitive effects, plaintiffs still must show anticompetitive effects owing to the merger,using entirely different models (such as upward-pricing pressure models). And merging parties can overturn the presumption with evidence of procompetitive effects. If Albrecht is saying that antitrust courts merely look at market structure to decide cases, he is attacking a straw-man.

Other Policy Implications

Let’s get back to reality. Here’s how the New York Times described the contribution of Aghion and Howitt, as summarized by the Nobel committee:

Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt shared the other half of the award for what the committee described as “the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction.” They built a mathematical model for growth, with creative destruction as a core element.

The committee described creative destruction as “an endless process in which new and better products replace the old.” They used the example of the telephone, in which each new version made the previous one obsolete, from the rotary dial phone in the early 1900s to today’s smartphones.

Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt’s work shows how economic growth can continue despite companies being sidelined by the innovation of other firms. Their work can support policymakers in creating research and development policies, the committee said.

The laureates’ work shows “we should not take progress for granted,” Kerstin Enflo, a member of the Nobel committee, said during a news conference in Stockholm. “Instead, society must keep an eye on the factors that generate and sustain economic growth,” she added. “These are science-based innovation, creative destruction and a society open for change.”

A narrow reading of this passage suggests that the policy implications of Aghion’s and Howitt’s work should be limited to “research and development policies.” Even under this lens, proponents of policies like subsidizing medical R&D, green energy technologies, or broadband infrastructure could claim a new quiver in their bow. To take broadband investment as an example, high speed internet connectivity generates spillovers across the economy and promotes growth by enablingapplications in myriad connected industries, as demonstrated here and here.

When announcing their award, the Nobel Prize committee noted that “Policy should support the innovation process,” and that “science-based innovation” was among the factors that “generate and sustain economic growth.” Upon receiving the award, Howitt reportedly said that the biggest advances in technological progress “have involved cooperation between governments, universities and businesses.” This is confirmed by countless examples of public investment pushing technology forward. One notable recent example was Operation Warp Speed, a public investment into Covid-19 vaccine development and production. Another public investment, the BEAD Program, allocated billions to states to expand high-speed Internet access.

Would this year’s Nobel prize winners embrace other interventions in the economy? Say, to permit publishers to collectively bargain against Internet behemoths to ensure that content does not vanish? Perhaps, given their apparent fondness for competition and government programs. But rather than reading the tea leaves, we could just ask them. Or we can recognize that there are limits to what a Nobel prize can say about our pet policy ideas.

The proposed merger of the Union Pacific (UP) and Norfolk Southern (NS) railroads would consolidate ownership and control of a significant part of the central arteries or “trunk lines” of the rail network in this country. Currently, four railroads control most of these key components of the rail network, especially for the east-west service, and each has a clear regional dominance. The other two major trunk line railroads are the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) and CSX. A number of “branch lines” extend out from the trunk lines, and they are often operated by short line railroads. Although there are 600 short lines, a number of them have common ownership.

Proponents of the UP-NS merger argue that it would allow the combined railroad to operate trains from the west coast to the east coast without having to switch the cars between rail lines at some transfer point. It is speculated that if the UP-NS merger is allowed, the BNSF and the CSX would then seek to combine, creating even more concentrated control over trunk lines. The current position of the BNSF and CSX is that, even without a merger, they will jointly offer through service from west coast ports to various locations in the eastern half of the country. This service would use the same train for the entire trip with crews changing as the train moves from one system to the other. Notably, the routes that they propose for this combined service will directly overlap and compete with the UP-NS lines. All the major trunk lines already share track usage in some places with each other or with short lines. Furthermore, Amtrak, which only owns a few lines in the Northeast, has operated trains on the trunk lines of all major railroads for its nationwide services since its creation in 1971. In addition, many of the freight railcars in use belong to third parties that use them for their own goods or lease them to others for use. All of this shows that ownership of trunk lines is not essential to the operation of freight or passenger service on those lines.

Increased consolidation of ownership of trunk lines might induce their rationalization and enhancement to facilitate more efficient movement of trains. But this would come at the cost of increased dominance of these essential transportation facilities. Moreover, much of the rationalization and improvement is rational conduct by each major trunk line without any merger. Hence, the proposed UP-NS merger should be forbidden as long as the resulting company both owns the tracks and controls their use.

Beware the Bottlenecks

Trunk lines can be understood as “bottlenecks” through which the bulk of rail freight must pass. Ownership of trunk lines confers the ability to control the use of the capacity—namely, whose trains at what price will operate on those lines. Because the owner also controls the dispatch of trains on the line, it has substantial capacity to affect the quality of service. For example, Amtrak, which enjoys a right to use trunk lines for its services, has a long history of problems of having its trains delayed so that the trunk line owner can send the latter’s freight trains ahead. Where freight lines share track use rights, similar disputes are not uncommon between the track owner and the other railroad sharing that track.

What is concentrated is the control over the track itself. Major interstate highways are a single system with multiple users. The same is true of the inland waterways. Should ownership of railroad trunk lines be separated from operation of freight service by multiple users? Amtrak’s and freight lines’ shared use of some trunk lines suggest that operating freight and passenger trains do not require owning the trunk lines on which those services operate. Moreover, while the capacity of any rail line is ultimately limited, with proper scheduling and dispatch these lines can accommodate substantial increased use. It follows that if ownership of the trunk lines were separated from the operation of freight service, it is probable that the number of competitors in providing such service would increase. Freight rates would likely decline, and assuming proper coordination of use, service itself would increase in efficiency. In particular, services such as the movement of container shipments would likely increase significantly, as trucking companies as well as new entrants would be able to develop a range of through services. The same might be true for passenger service, but given low total demand, this seems unlikely except in a few potentially high-volume routes

The collaboration of BNSF and CSX to provide a through freight service from coast to coast absent any merger demonstrates the feasibility of such service. Not surprisingly, that proposed service will focus on competing directly with the potential (merged) UP-NS services. This highlights the importance of competition in stimulating innovation in transportation service. Notably, the other ports on the west coast that BNSF serves, but which do not have UP-NS alternatives, are not in the through services package.

As noted, there are significant problems with the coordination in the use of trunk lines. There are ways to coordinate use to facilitate more efficient shared use of track. The railroad controlling the line, however, has limited incentive to resolve those problems because it has a conflict of interest. Its rational goal is to maximize its own use rather than facilitate the use by others whether they provide a distinct service like Amtrak or are competitors in freight service as in the case of shared track rights.

Experience with Separating Ownership from Operation

Some countries have experimented with separating ownership of the tracks and licenses for operators to use those tracks to stimulate competition in rail services. A leading example is the United Kingdom. In the 1990s, the publicly owned national rail system was terminated. Regional passenger services devolved into private ownership but retained a localized monopoly. In addition to the regional services, long-distance passenger services emerged that provided some competition. Freight service was similarly privatized but in a manner that encouraged competition. A distinct but private authority maintained the tracks and provided coordination of services.

By 2024, parts of that experiment failed. The government had retaken the responsibility for ownership and coordination of the rail system itself because of concerns about maintenance of the rail lines. It has similarly retaken ownership and operation of some regional passenger services that had persistent problems in both finances and operations. In 2024, the new Labor government determined that as the remaining contracts for the regional service expire, their passenger service will be absorbed into a state-owned entity that will provide service in the England and the parts of Wales and Scotland where those regions had not already recaptured public ownership of local passenger service.

On the other hand, the independent freight services and long-distance passenger services will continue to operate. The distinction is that the regional services were local monopolies of rail passenger service, while both the freight services and the long-distance passenger lines operated in a competitive environment. There are five major freight services competing in the UK market. The American short line holding company, Genesee & Wyoming, owns one of the leaders, Freightliner, which is particularly strong in handling containers, including offering its own trucking service to deliver the container.

Remedy Design for the STB

If the UP-NS merger is to be allowed, there should be separation between ownership of the tracks and operation of the freight services on those tracks. Because the law exempts these mergers from standard antitrust review, the decision will come exclusively from the Surface Transportation Board (STB), whose authority to regulate the operation of the rail system extends beyond standard antitrust criteria to encompass a broader concern for the overall public interest in the rail system. If it adopts this strategy, the STB should also require the BNSF and CSX to make a similar separation of rail lines from their operation of freight services. Indeed, this separation should also apply to the other two Class I railroads—the Canadian Pacific Kansas City and Canadian National. Doing so would immediately create six freight service operators even if the STB did not require subdivision of the operating companies. Of course, new entry would have to be authorized as well. The Genesee and Wyoming Railroad is among the most obvious entrants given its UK experience and expertise. The STB would have to develop standards for entry and define the rights of such firms. It might be necessary to have criteria for use of trunk lines such as those into the Los Angeles area, which might have capacity limits.

A central question would be the form of ownership and management of the trunk system. Private ownership would risk exploitation, as such an owner would have monopoly power over the use of its track. The STB would have to impose rate regulation to avoid overcharges. Perversely, the track owners will then have the incentive to make overly costly investments if rate regulation is based on the assets devoted to the business. This is the history of regulated public utilities where rates are based on the capitalized value of the investment in the facilities. If rates are not based on capital investment, however, there would be an incentive to underinvest in the maintenance and improvement of the rail lines. A related risk is the control over dispatch along lines. An owner might have incentives to favor some users over others or use this control to demand additional compensation for priority.

It is very hard to imagine that the American government would take ownership of the rail system even though it “owns” and maintains both the highway and inland waterway systems. Not only the UK, but many other countries have public ownership of their rail systems. Early in the development of America’s railroad system, states were often the owners of the lines that operating companies used and North Carolina still owns a major trunk line in that state. Indeed, Amtrak is a government entity reflecting the failure of private companies to maintain a successful national rail passenger system. But Amtrak’s problems with getting sufficient support to develop and operate its system cautions against government ownership. Indeed, the deferred maintenance for both the national highway system, especially bridges, and the failure to make timely investments in the inland waterways counsel against public ownership. All are dependent on Congressional appropriations.

The source of these problems, whether privately or publicly owned, is the conflict of economic interest between rail users and the track owner. Darren Bush and I have suggested that one solution to dealing with the operation of bottlenecks is to have the ownership rest in either a cooperative owned by the users or by creating a condominium type of ownership in which owners of specific use rights share ownership but not management of the overall entity. Both strategies assume that there are a significant number of users whose primary interest is in using the bottleneck as a means to provide some valuable good or service. Hence, the goal of these owners is to maximize the utility of the bottleneck for all its users. This means providing as much access as is technologically feasible, ensuring proper investment in maintenance, and providing the kinds of coordination that would again maximize the use of the resources involved. Our article showed that such strategies have in fact been used successfully in a variety of contexts—from cooperative grain elevators at a time when farmers faced very local, monopsonistic markets for their grain to electric transmission that facilitated the opening of competitive markets for the sale of electricity to local utilities.

In the case of railroads, given the goal is to have actual and potential competition for freight service between all major markets, the logical option for the trunk lines is that of a cooperative in which the users would collectively own and manage that essential element of the business. Given a large number of participants, a necessary element to ensure that the incentives to exploit or exclude are minimized, the day-to-day operations would have to be run by a board of directors and managers. The key here is that the incentives of management would be the efficient and open operation of the trunk system.

Remaining Challenges Are Big But Solvable