On November 1, Judge Florence Pan blocked the Penguin-Random House/Simon & Schuster merger. The Department of Justice’s primary theory of harm was that the merger would harm book authors by reducing advances. The decision prompted economist Hal Singer to ask his Twitter followers whether “the consumer welfare standard—which ranked consumers over workers in the antitrust hierarchy and fixated over short-run price effects—is officially dead?” (The written decision was unsealed on Monday, and the Court concluded that the acquisition “is likely to substantially lessen competition to acquire ‘the publishing rights to anticipated top-selling books,’ which comprise the relevant market in this case.”)

In a series of tweets responding to Singer’s question that echoed his recent scholarship on this subject, leading antitrust law professor Herbert Hovenkamp argues that the consumer welfare standard is very much alive and can accommodate harms to labor. For Hovenkamp, consumer welfare properly understood is a maximum welfare prescription, and thus already takes into account worker interests. While acknowledging that anticompetitive restraints on workers like non-compete and no-poaching agreements do exist, he asserts that these are ultimately secondary to, and should be subordinated under, labor’s alleged larger interest in maximum output in product markets, where its interests happen to align with consumers anyway. In other words, the status quo is fine.

Leaving aside the nearly one in five workers subject to non-compete agreements, who might disagree that labor market restraints are a secondary concern, it’s important to note at the outset how surprising Hovenkamp’s claim would be if it were true. In Hovenkamp’s telling, the coming of the consumer welfare standard in the 1980s rescued antitrust from the bad old days of overaggressive enforcement in the 1960s. However, 1980 happens to be about the time that wages started stagnating, after historically robust growth from the end of World War II into the 1970s. If consumer-welfare antitrust actually did help workers, the effects were so weak that they were swamped by the other policy components of neoliberalism happening at the same time.

But since we can’t rerun the last forty years with everything else held constant except the consumer-welfare revolution, let’s assess Hovenkamp’s case on its own merits. The argument is a simple one: labor is an input into production, and the demand for labor is ultimately derivative of the demand for products. Therefore, maximum output in product markets should not only lower prices for consumers, it should also raise the demand for labor, which would increase both employment and wages. In Hovenkamp’s words:

When product market output is strong and demand is growing, the fortunes of labor rise as well. Here, consumers are very largely in the driver’s seat. They make purchase choices, which in turn determine demand and thus the need for labor. So labor rides on consumer choice.

It would indeed be nice if any opposing interests of consumers and labor could be dissolved through the solvent of maximum output, with consumers winning first but labor nonetheless along for the ride. Alas, it is not so. Distributional conflicts, especially in the antitrust domain, are not so easily avoided.

Output expansion or economic growth is desirable because it has the ability to increase the size of the economic pie, allowing us all to have bigger slices without altering anyone’s relative shares. Hovenkamp is right that strong and growing demand is good for labor at the macroeconomic level, as strong aggregate demand means low unemployment and high worker bargaining power. But aggregate demand is determined by fiscal and monetary policy, not by “consumer choice.” While consumer choice does influence the allocation of demand between this or that good or service, it has no influence on its level. Consumers cannot will demand into existence in a depressed economy in which income and credit are hard to obtain.

When applied to antitrust, Hovenkamp’s desire to shoehorn worker welfare into an epiphenomenon of consumer welfare runs into insurmountable problems. In many instances, antitrust is asked to weigh in on wealth transfers between employers, consumers, and workers. Interests do conflict in the real world, and a monomaniacal focus on consumer welfare assumes away the wealth transfers that are paramount in many cases. Where anticompetitive conduct redistributes wealth from one side of the market to the other—the very cases that antitrust (and all) litigation is concerned, otherwise they would not be litigated—the maximum output rule offers no useful guidance. As a result, with consumer welfare as its lodestar, antitrust doesn’t have anything to say about a merger that would cause such a redistribution from labor.

Hovenkamp’s main case for the unity of worker and consumer interests rests on theories of classical labor monopsony with a uniform wage rate, a special case of monopsony where worker and consumer interests do actually align. Under this model, employers do not take wages as given by a perfectly competitive market. Rather, they have some discretion to set wages by selecting a point on an upward-sloping labor supply curve. While this allows them to pay workers below their productivity, it also makes them reluctant to hire more workers. Because classical monopsonists make so much profit from paying their current workforce less than their productivity, they don’t want to institute the uniform wage increases necessary to attract additional workers. The reason is that a higher uniform wage would mean raising wages for their currently underpaid workers as well. In classical monopsony, output is less than it would be under perfect competition: the outcome is not just an unfair redistribution from workers, it shrinks the size of the overall pie. Under classical monopsony, a maximum output rule would benefit both consumers and workers.

In this highly stylized model of the labor market, it is the power of workers to enforce the social norm of “equal pay for equal work” that actually creates the output-shrinking inefficiency: were the classical monopsonist able to pay each worker an individualized wage (as algorithmic management techniques increasingly allow employers to do), output would actually rise to the perfectly competitive level and the output reduction would disappear. But the unfair and unjust redistribution from labor would remain—employers and consumers would benefit, but workers would lose. In this case, a maximum output rule would benefit both consumers and employers, at the expense of workers.

Moreover, outside the strict assumptions of the classical monopsony model, buyer power in labor markets has the potential to increase output. Monopsony power is a function of workers’ outside options: the more limited the choice of employers, the greater the power of the employer over labor. Classical monopsony focuses solely on the wage rate. But employers don’t care only about wages. As economists from Karl Marx to Carl Shapiro and Joseph Stiglitz have long recognized, labor is a unique input in that “labor supply” does not capture what employers are really after. While the wage rate buys employers a workers’ time, what employers really want is effort. No one hires you for a job just to sit there for eight hours. And effort, just as much as wages, is a function of workers’ outside options: the more limited your choice of employer, the more you fear being fired, and the harder you will work to avoid that outcome. A merger in a labor market or a non-compete clause could therefore raise output—by making each employee work harder.

This is not a mere theoretical curiosity. There is evidence that hospital mergers harm nurses not by lowering their wages, but rather by increasing the number of patients for whom they must provide care. Nurses working harder can raise output and lower prices. Or take the example of Amazon: While it likely uses its monopsony power to pay workers less than their productivity, what it really excels at is extracting literally superhuman effort levels from each worker. The evidence is plain to see in the soaring musculoskeletal injury rates, caused by a super-fast pace of work. Should a hospital merger that increases output by lowering staffing ratios be waved through under a maximum output standard? It turns out there is simply no avoiding these distributional issues, and a “maximum output” rule does not resolve them.

Turning to specific antitrust policies, Hovenkamp singles out two for special opprobrium: the Robinson-Patman Act (RPA), and prohibitions on maximum resale price maintenance (RPM). In the consumer-welfare era, federal government enforcement of the RPA has virtually ceased, and maximum RPM has been permitted under the rule of reason since 1997. However, the RPA did protect workers, but in two ways that are contrary to the logic of output maximization.

First, a properly-enforced RPA would have prevented large retailers like Walmart from out-competing smaller competitors through raw buyer power over suppliers. RPA prohibits the extraction of discriminatory price discounts from upstream suppliers without a lower cost justification. This closes the growth channel through the ability to extract special discounts not available to competitors, but keeps open the growth channel deriving from superior productive efficiency.

Continued robust enforcement of the RPA, by preventing Walmart from squeezing upstream suppliers for price discounts, would have protected workers in a slew of upstream manufacturing jobs that have now been decimated by Walmart’s massive buying power. While the output-suppressing effects of classical labor monopsony are rooted in there being a tradeoff between employee quit rates and the wage rate, these effects do not cross over to monopsony power over non-labor sellers like suppliers to large retailers. In these cases, the buyer is likely to use their power to demand (and receive) more output at lower prices. Once again, buyer power in supply chains may raise output and reduce prices (if Walmart passes its gains on to consumers), but at the expense of firms and workers upstream in these supply chains. This kind of buyer power accounts for perhaps a full ten percent of wage stagnation since the 1970s—about the time RPA enforcement ceased. Once again, this is a distributional conflict that can’t be wished away.

Second, continued enforcement of RPA could also have protected retail jobs at Walmart’s higher-wage direct competitors from this kind of unfair competition. As we now know, Walmart’s entry into local retail markets on the back of RPA violations (along with union-busting and other unfair competitive tactics) has suppressed local wages, even if it raised its own profits and boosted the output of cheap goods. The classical labor monopsony channel was overwhelmed by Walmart’s broader monopsony power over its supply chain. One could argue that the gains to consumers outweigh the harms to workers, but not that their interests are identical.

Turning to maximum resale price maintenance (RPM), the workers affected by these policies certainly do not gain from “maximum output.” In fact, franchisors and other upstream firms use RPM to enforce a low-wage business model on the downstream firms under their control. McDonald’s may well be able to sell more quarter pounders for lower prices under maximum RPM, but at the expense of workers at McDonald’s restaurants. In franchising industries, what vertical restraints like RPM do is enforce a low-wage business model on downstream franchisees, by taking virtually every variable affecting profits out of the franchisees’ choice set—not just prices but suppliers, business hours, and product mix. The effect is to force franchisees to focus intensively on the one variable they can control—lowering labor costs. As one McDonald’s franchisee explained to the Washington Post, when she complained to McDonald’s about its RPM policies the company told her to “just pay your employees less.”

While Hovenkamp seeks to outsource the goals of antitrust law to economic theory, I have argued that economics does not support “just maximize output” as a solution to question of advancing labor’s interests. But even if economics did support Hovenkamp’s claims, the legislative history of of the Sherman Antitrust Act makes it clear that its authors were simply not concerned with neoclassical economic concepts like consumer welfare or maximum output. To the extent these theoretical constructs existed at the time, they were ignored by legislators. Rather, Congress wrote the Sherman Act to guarantee to every person the opportunity to succeed or fail in the market on the basis of fair competition, limit the political power of the wealthy, and, most relevant to our purposes, prevent unfair wealth transfers from consumers, farmers, and labor to large corporations and cartels. In other words, Congress was concerned with the distribution of wealth, power, and opportunity.

Economics does have a role to play in antitrust. Power, wages, prices, and yes, output are all quantities, that must be accurately measured and quantified to help inform new legislation in Congress and competition rulemakings by the Federal Trade Commission. And whatever criticisms one might level at economists, no one else has stepped up to develop better techniques for quantification than us. But neoclassical economic theory cannot be the solvent some want it to be. Economic theory cannot provide the normative values antitrust agencies and courts must use to evaluate competitive conduct, particularly where labor is threatened but consumers are not. Only a democratic legislature can do that. And Congress specified other goals than maximum output when it wrote our antitrust laws.

For decades, one analytical dichotomy has been particularly influential in antitrust law. Courts have drawn a sharp distinction between trade restraints among rivals (or horizontal restraints) and restraints among firms in a buyer-seller relationship (or vertical restraints). The body of judge-made antitrust law treats the former as suspect and the latter as generally benign.

In a 2004 decision, the Supreme Court described collusion among rivals as “the supreme evil of antitrust.” Accordingly, price-fixing and market allocation agreements among competitors are per se, or categorically, illegal. By contrast, the Supreme Court accepted vertical restraints as, at least in theory, useful methods of protecting against assorted forms of free riding and therefore entitled to a strong presumption of legality. The Court in 2018 asserted, “Vertical restraints often pose no risk to competition unless the entity imposing them has market power.” Typically, the government and other plaintiffs challenging vertical restraints must show harmful effect on “output” to establish their illegality.

In practical terms, as a June district court decision shows, this horizontal-vertical distinction means that McDonald’s franchisees cannot come together to agree not to hire each other’s employees, but McDonald’s USA generally can prohibit its franchisees from hiring each other’s employees as a condition of becoming a franchisee—which amounts to the same thing in practice.

Yet this analytical distinction does not withstand scrutiny. The horizontal (bad) versus vertical (good) dichotomy is false as a descriptive matter. Stepping away from judicial precedent on the Sherman Act and examining antitrust law and adjacent areas of law more broadly reveal a more complicated picture. This broader body of law treats certain horizontal restraints among certain classes of actors as desirable. Congress has identified some forms of coordination among rivals in their dealings with powerful buyers as beneficial, such as labor unions and farm cooperatives, and authorized them. And it has not deemed vertical restraints, such as exclusive dealing arrangements, to be generally benign. Further, as a normative matter, remaking antitrust law as instrument for dispersing power requires abandoning a simplistic horizontal versus vertical distinction.

In multiple statutes, Congress rejected the notion of horizontal collusion as the supreme evil of antitrust. Instead, it identified “collusion” among certain classes of actors toward certain ends as socially beneficial cooperation. In the Clayton Act, it authorized an indeterminate set of concerted activities by workers, farmers, and ranchers. The law states:

Nothing contained in the antitrust laws shall be construed to forbid the existence and operation of labor, agricultural, or horticultural organizations, instituted for the purposes of mutual help, and not having capital stock or conducted for profit, or to forbid or restrain individual members of such organizations from lawfully carrying out the legitimate objects thereof; nor shall such organizations, or the members thereof, be held or construed to be illegal combinations or conspiracies in restraint of trade, under the antitrust laws.

Congress offered critical clarification in subsequent enactments. In 1922, Congress passed the Capper-Volstead Act, which authorizes “farmers, planters, ranchmen, dairymen, nut or fruit growers” to engage in collective processing, preparing, handling, and marketing of their products. A similar right was subsequently granted to fishers in 1934. And for workers, Congress, in the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, granted them a statutory right to engage in concerted activity and prohibited employers from dismissing workers for unionization and other collective action. And in authorizing certain forms of coordination among these groups, lawmakers established public oversight of their joint activity, entrusting the Secretary of Agriculture, Secretary of Commerce, and National Labor Relations Board to supervise the cooperation of farmers, fishers, and workers, respectively.

In contrast to the Supreme Court’s generally positive view of them, Congress expressly restricted certain vertical restraints. In Section 3 of the Clayton Act, Congress targeted exclusive dealing (by sellers of commodities) when the effect of the practice “may be to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.” In other words, a non-monopolistic firm can engage in illegal exclusive dealing under Section 3. For instance, in a 1949 decision, the Supreme Court condemned exclusive dealing by an oil refiner and marketer that had a 23% share in the wholesale gasoline market in a group of Western states. And it did not stop with Section 3. In the Consumer Goods Pricing Act of 1975, Congress repealed two laws that had permitted states to legalize resale price maintenance agreements between manufacturers and distributors. When signing the bill into law, President Gerald Ford was clear what it would do: “make it illegal for manufacturers to fix the prices of consumer products sold by retailers.”

In statutory law, Congress rejected the horizontal (bad) versus vertical (good) dichotomy, and in doing so, took a nuanced approach. It expressly authorized certain forms of horizontal coordination and condemned particular vertical restraints. Accordingly, the rigid dichotomy is a judicially crafted doctrine and not an accurate description of the antitrust and related statutes.

In light of this statutory history, antitrust advocates and enforcers committed to reviving antitrust as an instrument for dispersing power in the economy should reject the current horizontal-vertical dichotomy. What courts consider collusion is sometimes beneficial cooperation, as Congress recognized. Labor unions permit workers to build power in labor markets and on the job and obtain a fair share of their firm’s wealth. Same with agricultural and aquacultural cooperatives. For many, these organizations are not vehicles for collusion but exemplars of solidarity and a solution to a power imbalance that drives wages and prices below fair levels.

Instead of being criticized for permitting “collusion,” Congress, if anything, should be faulted for not authorizing cooperation among more classes of comparatively powerless actors. Are workers, farmers, ranchers, and fishers the only powerless classes in the economy that should have the right to engage in concerted action? What about fast-food franchisees? Or Amazon flex drivers? Or even newspapers and other media being squeezed by Facebook and Google? Under current and indeed longstanding law, they cannot build power through collective action, despite being subordinated and exploited by some of the largest corporations in the world.

What courts have deemed “efficient” vertical restraints can be instruments of control and domination. Employers have robbed millions of workers of labor market mobility by requiring workers to assent to non-compete clauses. More generally, powerful firms across the economy use vertical restraints to dictate how nominally independent workers and businesses conduct their operations. For instance, Uber and other gig corporations insist their workers are independent contractors and, as such, not entitled to the rights and benefits of employment. Yet, through contract, they minutely control their fares, take-home pay, routes, vehicle condition, personal presentation, and even terms of work and dealing on rival platforms. These corporations have established a system of “control without responsibility” using vertical restraints. The gig economy is not an isolated example or novel, but merely the latest example of vertical restraints being employed as instruments of domination.

Legislators and federal regulators should embrace nuance. Horizontal coordination is sometimes good and sometimes bad; same with vertical restraints. Some restraints among rivals deserve categorical condemnation. For example, employers colluding to cap their workers’ wages or branded drug companies paying generic rivals to stay off the market are two examples deserving such strict treatment. (Ironically, despite its strong anti-collusion rhetoric, the Supreme Court has taken a more lenient approach to both practices in recent years.) While vertical restraints can be tools for subordination, that does not mean they always are and deserving of across-the-board illegality under all circumstances. Exclusive deals between a small manufacturer and a small distributor can provide long-term stability and attract external financing for both firms. And resale price maintenance provisions can induce retailers to carry a new consumer goods product by setting minimum margins.

As these examples show, inverting the current horizontal-vertical distinction would be a mistake. The deficiencies of the current dichotomy—horizontal (bad) versus vertical (good)—do not call for embracing another false dichotomy—horizontal (good) versus vertical (bad)—as an analytical tool. Instead, Congress and agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission should eschew high-level binaries and, through public input and expert study, establish rules and presumptions for specific restraints.

In a response to a recent speech by FTC Chair Lina Khan concerning merger enforcement, Sean Heather, a Senior Vice President of the Chamber of Commerce argued that “Chair Khan’s FTC would seriously damage the economy’s dynamism.” This statement exemplifies the constant refrain among conservative critics of greater antitrust enforcement that such efforts will result in a weaker macroeconomy.

In April, FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson delivered a talk claiming that the FTC’s endeavor to enforce antitrust law reflects an embrace of Marxism and Critical Legal Studies. Wilson’s screed was rife with errors and misunderstandings about the history of economic thought and philosophy. She concluded that “In Short, perspectives that draw on Marxism and CLS [i.e. those that reject the Chicago School of antitrust] if embodied in antitrust law and policy, will undermine both the incentive and the ability to innovate and will erode the dynamism of the U.S. economy.”

In latest Antitrust magazine, the same argument in support for lax enforcement appears again. This time, Jonathan Jacobson, defending the Consumer Welfare Standard, writes “It [the consumer welfare standard] has held up well for those thirty years, and the U.S. economy has flourished as a result.” Joshua Wright and Douglas Ginsburg proffered the same evidence-free claim in their 2013 Fordham Law Review article: “Indeed there is now widespread agreement that this evolution toward welfare [the consumer welfare standard] and away from noneconomic considerations has benefited consumers and the economy more broadly.”

The specious claim that freeing large corporations from the shackles of regulation will benefit the economy by achieving higher levels of growth and performance has no substantive evidentiary basis. Upon hearing such Panglossian claims repeated ad nauseam, one might be tempted to believe that greater economic growth and universal prosperity has accompanied the Neoliberal revolution. But this is not the case.

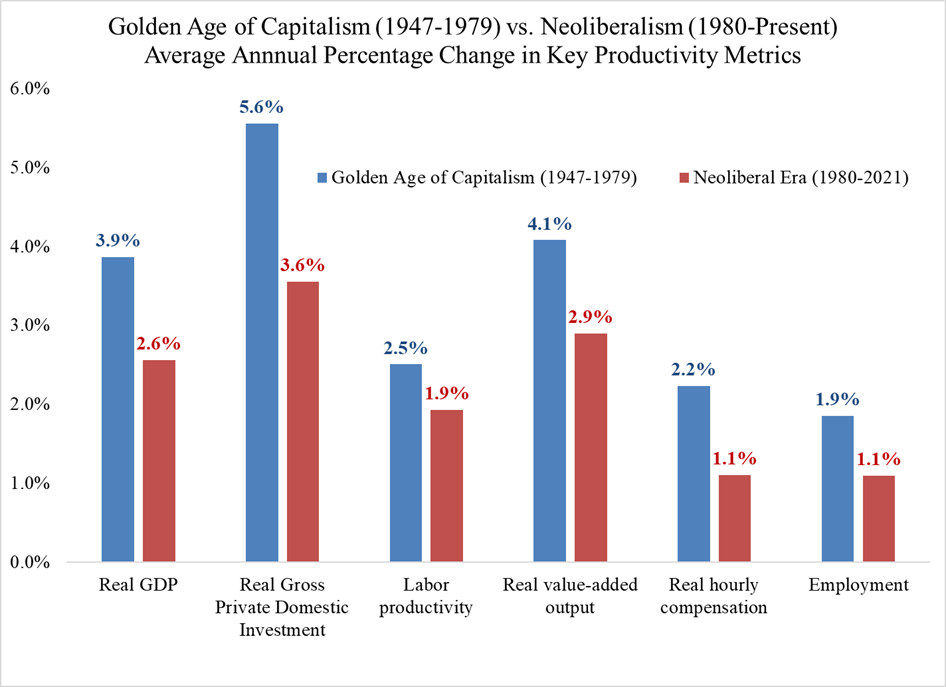

Indeed, the neoliberal revolution that occurred around 1980–with the election of Ronald Reagan and the appointment of James Miller III (pictured above) as chair of the FTC–reasserted the dominance of large companies, undermined regulation and antitrust, and destroyed America’s union movement, also harmed the economy. In comparison with the period from 1948 to 1980, the period beginning with the rise of neoliberalism after 1980 saw a reduction in growth, lower rates of productivity, lower investment rates, lower growth rates in wages, and greater inequality.

Studies specifically link the inferior post-1980 economic performance reflected in the chart above to the reduction in antitrust enforcement. Gutierrez and Philippon directly tie the drop in corporate investment to rising concentration: “We argue that increasing concentration and decreasing competition in many industries explains an important share of the decline in investment.”

Other papers have examined the relationship between antitrust enforcement and productivity growth. Filippo Lancieri, Eric Posner and Luigi Zingales, citing the seminal work of Robert Gordon, state that “there is no evidence that productivity growth increased as a result of the relaxation of antitrust.” Paulo Buccirossi and his coauthors studied the impact of antitrust enforcement (and other factors) on total factor productivity growth in 12 OECD countries. The authors found the oppositive of the conservative claim: “Our results imply that good competition policy has a strong impact on TFP growth.” In 2014 the OECD published its “Factsheet on how Competition Policy Affects Macro-Economic Outcomes.” Again, the basic finding is that “industries where there is greater competition experience faster productivity growth.”

We find no evidence that the reduction in antitrust enforcement that accompanied the ascension of the consumer welfare standard in the 1980s as the lodestar of antitrust enforcement had any positive impact on growth, productivity or investment. The quest for economic growth ostensibly motivates free market ideology; yet this ideology maintains the myth that it serves the social welfare. Economic evidence says otherwise: the neoliberal revolution destabilized the macro economy and has led to inferior macroeconomic performance. FTC Chair Lina Khan and the New Brandeis School continue to advance policies that will benefit growth and innovation, even if it does not help billionaires accumulate even more obscene levels of wealth.

Platform Most-Favored Nations clauses turn private unilateral market power into economy-wide inflation.

It’s fair to say that no one has any good explanations for why post-pandemic inflation has been so hard to tame. But plenty of people think they know what isn’t the cause: concentration and market power on a macroeconomic scale that enables dominant firms to raise prices without fear their customers will leave for the competition (since there isn’t any). Critics, like Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell and NYU economist Chris Conlon, derisively call this hypothesis “greedflation” to lampoon the suggestion that a sudden epidemic of greed has caused powerful firms to exploit the market power they previously had, but weren’t using, at least not against consumers.

But the idea that dominant firms generally — and platforms in particular — had market power they weren’t using used to be commonplace. And it’s entirely sensible that if they weren’t using their market power then (so as to accumulate more of it), they would use it now. The strategy of predatory pricing is to set a low price to lock in customers and drive out the competition, then charge high prices later to “recoup” losses. For many decades, the prevailing view has been that predatory pricing is unlikely because charging monopoly prices in the recoupment phase will just attract entry, which will make the initial predatory phase irrational to attempt. As Justice Powell wrote in the 1986 case of Matsushita v. Zenith Radio Corp., “predatory pricing schemes are rarely tried and even more rarely successful.” In the 1993 case Brooke Group v. Brown & Williamson, the court held that there must be a “dangerous probability” of recoupment for a predatory pricing claim to succeed. The DOJ last tried a predation theory against American Airlines in 1999 for its conduct defending its monopoly hub at the Dallas-Fort Worth airport. That claim ultimately failed, an underappreciated inflection point in the oligopolization of the airline industry that’s responsible for today’s high prices.

My claim is that platform MFNs are a hidden cause of the current macroeconomic inflation. An economy full of dominant intermediaries, all of whom use MFNs and their non-price equivalents, is an economy primed to turn private unilateral market power into widespread macroeconomic inflation when it comes time for recoupment.

The reason predatory pricing isn’t supposed to work is that recoupment invites entry. But instead, imagine that during the recoupment phase, the incumbent doesn’t just charge a high price for his own product; he also gets to dictate that no one else is allowed to charge a lower price. Then entry isn’t such a potent threat, because entry or no entry, the incumbent doesn’t have to worry about being undercut. That is exactly what so-called Most-Favored Nations (MFN) clauses allow.

The phrase “Most-Favored Nations” clause refers to international trade negotiations, in which two (or more) trading partners agree by treaty to give one another as favorable trading terms as are given to any other trading partner. Such clauses are stronger than setting tariffs at any given level, because they automatically adjust if other trading partners are given better terms, preventing discrimination.

When wielded by a dominant platform, however, an MFN can be anticompetitive. Platform MFNs have a similar structure, but much different economic significance since they are typically imposed by one dominant platform on upstream sellers on the platform, rather than mutually agreed to by trading partners. By using an MFN, a platform is restricting the autonomy by which sellers on the platform can set prices on other platforms, other sales channels (such as brick-and-mortar retail), or direct-to-consumer sales. The point is to prevent other channels from getting preferential terms from the seller, and attracting consumers away from the dominant platform with discounts. Given that the dominant platform can’t be undercut, they don’t have to worry about entry. That, and not assumptions about mechanistic two-sided network effects, is the real reason so many platform industries are monopolized.

Now, consider what happens when a platform starts raising its take rate, the share of gross seller revenue the platform takes as its cut from any sale. In response to this increase in the marginal cost of selling on that platform, the seller would most likely increase price on that channel and decrease the price elsewhere to create a price differential that induces customers to switch. Savings from the lower take rate on the rival platform can be shared with the customer in the form of lower prices. But the MFN bars the seller from steering its customers that way, effectively serving as an anti-steering provision. Moreover, the MFN says that if the seller increases price on the one platform that increased its take rate to cover the higher cost of selling there, it has to raise prices on all channels in order not to steer customers elsewhere. Therein lies the mechanism by which the unilateral increase in the take rate imposed by one dominant platform translates into price rises across all channels of distribution. And dominant platforms have been increasing their take rates quite a bit in the past few years.

How prevalent are platform MFNs? It’s fair to say that most of the platforms that have come to dominate each market segment use them, including rideshare and food delivery apps, mobile app stores, travel booking, and private temporary accommodation. They are typically one of several varieties of anti-steering restraint that dominant platforms impose to lock in counterparties both upstream and downstream. Credit card companies are notorious for preventing merchants from discounting their items for users who don’t pay with a credit card (or pay with a card with a lower interchange fee), requiring them instead to raise their prices for all customers when credit card fees go up. Merchants are even prohibited from simply telling customers that they, the merchant, prefers they pay with cash (or use a lower-fee card). The upshot is a giant transfer of wealth away from customers whose credit isn’t good enough for the cards that offer decent rewards (but still have to pay the high prices merchants charge everyone), with credit card companies taking the lion’s share and the wealthiest customers getting crumbs by way of rewards programs that they think are a great deal.

My claim is that platform MFNs are a hidden cause of the current macroeconomic inflation. An economy full of dominant intermediaries, all of whom use MFNs and their non-price equivalents, is an economy primed to turn private unilateral market power into widespread macroeconomic inflation when it comes time for recoupment. And investors in dominant platforms have been clear that now is when they want a return on their investment. As dominant platforms have increased take rates to recoup the low prices they charged to monopolize the market, in order to reassure their investors during an equity market decline, especially for tech stocks, the MFN means everyone else has to follow suit. That looks to consumers (and apparently to economic policy pundits) like a general price increase that can’t be tied to individual firms, even though, in fact, it can.

You can thank the conservative Supreme Court majority for the current inflation.

How is this allowed, you may ask? Beyond the weakening of predatory pricing caselaw thanks to simplistic theories that disregard the possibility of MFNs, the other area where antitrust enforcement has lost its teeth is against vertical restraints imposed by dominant firms to bind dependent affiliates (of which MFNs are one, potent example). This decades-long failure culminated most recently in the 2018 Supreme Court case Ohio v. American Express.

The majority opinion in that case, written by Clarence Thomas and co-signed by Justices Roberts, Alito, Kennedy, and Gorsuch, gave a green light not only to American Express to raise its take rate without fear that its anti-steering restraints would face challenge, but to two-sided platforms with market power more broadly. It said that harm had to be shown to consumers from the challenged conduct, and that since credit card transaction volume was increasing, output hadn’t been restrained on the downstream side of the platform and therefore consumers hadn’t been harmed. It didn’t even entertain the possibility that anti-steering restraints would enable higher credit card fees and therefore higher prices across the board, and that the higher the fees they enable, the more credit card companies would want to subsidize consumers to use their cards in preference to cash. You can thank the conservative Supreme Court majority for the current inflation.

But that just follows on decades of crediting ostensibly economic justifications for anticompetitive vertical practices like loyalty pricing, which encourages consolidation, monoculture, and supply-chain vulnerability such as we saw earlier this year with the baby formula shortage. It occurred because of a safety violation at one of a very few plants that manufacture baby formula at scale. The reason there are so few is the loyalty-pricing practices invited by state-level Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) programs, which enter monopolistic requirements contracts in exchange for bulk discounts. The original idea was supposed to be that this would save money on a public program and thus be fiscally responsible. The only problem is that it drove consolidation, thus making the industry catastrophically vulnerable to disruptions.

The real “Inflation Reduction Act” should have been a wholesale overturning of the lax jurisprudence of vertical restraints that the federal judiciary has imposed since 1977.

Beyond bad caselaw, however, the other culprit is the absence of any will on the part of Congress to change it. As far as I know, no federal legislation has been proposed to overturn Ohio v. American Express and the whole panoply of lax antitrust jurisprudence of vertical restraints imposed by dominant market actors—despite the fact the 2020 House Majority Report of the Antitrust Subcommittee explicitly called for such legislation. Even as Congress has spent the last year or more decrying high inflation, and the Fed has been tasked with preventing it with the only tool it has, a severe economic slowdown, none of the legal levers available to enhance platform competition and threaten the profits of the economy’s most powerful gatekeepers and middlemen has been pulled.

Any policy agenda to curtail price increases and clamp down on anticompetitive business models like predatory pricing and recoupment should disregard the kinds of theoretical arguments that underlay their legalization in the first place: that consumers somehow benefit from economic coercion, and that entry would “naturally” fix any competitive problem before a court does. The real “Inflation Reduction Act” should have been a wholesale overturning of the lax jurisprudence of vertical restraints that the federal judiciary has imposed since 1977 along these lines.

The good news is that some economists are beginning to recognize the nexus between inflation and market power. Last week, the OECD released a report spelling out the connection in detail, documenting the empirical literature that links higher prices to the exercise of power. Unfortunately, gatekeeping economists — as well as their hangers-on in the tech-billionaire-owned media — still scoff at the claim that market power might be to blame for inflation without considering it on the merits. They should reconsider their tendency to discredit outsiders who might have a better sense of how the economy works than they do. At the very least, they should remember that the first rule of scientific inquiry is to keep an open mind.

For those following me on Twitter, you might know that I’m a bit fixated with inflation, its underlying causes, and how best to arrest it.

Here’s what we know after one year’s worth of controversy: (1) inflation is largely coming from two sectors of the economy, housing and electricity; (2) inflation does not seem to be slowing from interest rate increases, with core inflation of 6.6 percent hitting a 40-year high in September; and (3) neoliberal economists cannot fathom a theory of inflation that doesn’t blame workers.

I will be writing plenty on alternative remedies to arresting inflation, including de-concentration efforts, temporary industry-specific price controls, and FTC enforcement of invitations to collude. But in this piece, I wanted to stick a fork into the traditional view that inflation is best tempered with interest rate hikes.

The theory behind this view is that the labor market serves as a barometer to how hot the economy is running. As unemployment declines, the story goes, workers demand higher wages due to their newfound bargaining power. Profit-maximizing firms raise the price of their products in response to rising labor costs, yielding an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation, as predicted by the Phillips Curve. Higher interest rates make investment projects less attractive by raising the cost of capital. Slow the labor market by making investments less attractive, demand for workers needed to staff new projects will decline, wages will fall, demand for goods and services by those underemployed workers will decline, and the rest of the economy will naturally cool down.

This theory is badly antiquated. There may have been a time when output and labor markets were competitive, prices were set at marginal costs, and wages were set at a worker’s marginal revenue product. But that time, if it ever existed, has come and gone.

In many industries, particularly concentrated ones with high fixed costs—or industries dominated by what some economists have dubbed “superstar” firms—prices are untethered to labor costs. A pharmaceutical company doesn’t set its drug price based on the salaries of researchers. A gas station doesn’t set its price based on the attendant’s hourly wage. A hotel doesn’t set its nightly rate based on the wages of the cleaning crew. A car rental company doesn’t set its price on the wages of the worker sitting near the checkout booth. A university doesn’t set tuition based on the wages of its adjunct professors. I could go on.

Given the fixed-cost nature of these industries, many prices in the economy are set to maximize revenue, which is purely a function of the demand elasticity facing the firm. Wages don’t enter the pricing calculus, as they too are perceived (at least in part) as a fixed cost.

Now I will grant that in certain labor-intensive industries, such as coffee shops and diners, prices will be tethered to labor costs. But these industries are not the drivers of inflation. Inflation is coming from concentrated industries such as food production, energy, and rent (more on that in my future work).

Even in some labor-intensive industries, such as sports, the price for pay-per-view does not rise with player payouts. Prices again are set based on consumers’ willingness to pay for the product. The players and owners divide a fixed pie, and an increase in the players’ share does not cause prices to rise.

Another reason why wages and prices have become untethered, aside from the evolution of our economy to high fixed cost industries, is growing monopsony power and the accompanying erosion of worker bargaining power. Employers with buying power drive a wedge between their workers’ marginal revenue product and wages, based on the (low) elasticity of supply they face. This markdown below marginal revenue product is the same phenomenon as we see when monopolists mark up prices above marginal costs in inverse proportion to the elasticity of demand they face.

When productivity increases, an automatic increase in wages no longer follows, as monopsony power now disturbs the the mapping from productivity into wages. Put differently, monopsony power has weakened, if not entirely severed, the linkage between prices and wages. Employers with buying power don’t need to acquiesce to wage demands: companies like Amazon and Starbucks have fought desperately against offering even the most meager concessions to workers. And even if they do, they already enjoy a sufficiently comfortable profit cushion that they don’t need to automatically revisit prices. Hence, an increase in wages won’t necessarily lead to an increase in prices.

But don’t take my word for it. A recent paper by two economists, David Ratner and Jae Sim of the Federal Reserve Board, shows that labor market policies that have eroded worker bargaining power are the source of the demise of the Phillips curve, which predicts that inflation rises as unemployment falls. As unemployment fell from 6.5 percent in 2009 to 3.5 percent in 2019, however, inflation showed no signs of increasing, or what is called “the missing inflation” puzzle. Ratner and Sim conclude that the “collapse of workers’ bargaining power” flattened the Phillips curve. The authors point out that, using their models in which workers bargain to keep the price-cost markup as low as possible so that wages and the labor share would be larger, the decline in worker bargaining power can explain the secular decline of the labor share, the secular rise of the profit share observed since the 1980s, and the stock market capitalization ratio.

Take the case of Starbucks, which is fighting off an attempt at unionization. Given the lack of bargaining power among its workers, when Starbucks raises the price of a latte, most of the price hike falls to the bottom line. If the workers were to unionize and demand a greater share of the pie, Starbucks might be less inclined to raise its prices, knowing that some of those gains would now be shared with workers. Continuing this union hypothetical, if workers were to become scare due to a decrease in unemployment, the union could extract higher wages, which likely would be passed on to consumers in the form of higher latte prices—revealing a steeper Phillips curve.

A flattened Phillips curve means that a decrease in unemployment that should, in theory, give workers greater bargaining power, doesn’t have any affect on prices (even if wages modestly rise) and thus inflation. Why? Because the power imbalance is so skewed in favor of employers that the small increase in the scarcity of workers doesn’t materially move the price needle (let alone the wage needle). In the post-Covid era, wage inflation peaked in March 2022 at just 6.8 percent, but for the reasons explained above, that change likely didn’t contribute to inflation, which outpaced wage growth in the same month. As explained by ESI’s Josh Bivens, “If the only change in the economy over the past year had been the acceleration of nominal wage growth relative to the recent past, then inflation would be roughly 2.5–4.5% today, instead of the 8.6% pace it ran through March.”

A flattened Phillips curve also implies severe labor market dislocations would be required to arrest inflation via rate hikes. As explained by Seccareccia and Romero in an INET blog, “the flatness of the relation [between unemployment and inflation] implies an immensely high sacrifice ratio if pursuing a Volcker-style strategy … since it would require excessively high unemployment to get the inflation rate down by even a very small increment.” Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers claims that we now need five years of six percent unemployment to curb inflation.

Despite these horrific tradeoffs, the church of neoliberalism led by Summers, preaches that monetary policy that reduces worker power (by creating unemployment) will eventually albeit painfully lead to lower prices and slowing inflation. Ironically, Summers co-authored a Brookings research paper in 2000, before inflation took hold, in which he argued that to arrest the decline in labor share, “institutional changes that enhance workers’ countervailing power—such as strengthening labor unions or promoting corporate governance arrangements that increase worker power—may be necessary (but would need to be carefully considered in light of the possible risks of increasing unemployment).” It is not clear whether Summers would continue to advocate for worker power in an inflationary environment.

In sum, managing inflation via interest rate hikes is an outmoded school of thought that may have worked when labor markets were more competitive and the power balance between workers and employers was evenly split. Given the severing of the nexus between wages and prices, it is time that we abandon the old tools and explore alternatives that arrest the source of price hikes at their source. This will be the subject of future pieces.

The Democrats are in trouble. With the midterms less than two weeks away, a New York Times/Siena College poll is the latest to show Republicans gain as voters get increasingly anxious about the economy and high inflation. While the Times poll has received a lot of media attention, its findings are hardly surprising. In fact, it has been clear for quite some time that when it comes to the issue that voters are most concerned about — soaring prices — Dems lack a coherent message.

Not that there is a shortage of things to say about inflation that will connect with voters. By now, for example, we know that while inflation is driven by many factors — Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the breakdown of global supply chains, and the devastating effects of climate change-related droughts on American farmers — one of the primary drivers of US price hikes is monopoly power. Earlier this year, a paper by Boston Fed economists Falk Bräuning, José L. Fillat, and Gustavo Joaquim showed the link between inflation and the increase in concentration over the past two decades. And a Roosevelt Institute paper by Mike Konczal and Niko Lusiani showed that markups increased dramatically in 2021 as companies with market power exploited the pandemic to raise prices above costs. With profit margins at a 70-year high, the Groundwork Collaborative has assembled dozens of examples of CEOs boasting about their ability to jack up prices and pin the blame on inflation during earning calls. Going after corporate price-gougers at a time of surging prices seems like a no-brainer.

It’s not that voters are particularly skeptical of this explanation, either. In fact, despite the best efforts of neoliberal economists to deny any connection between market power and inflation, polls show that a majority of Americans believe that profit-maximization is driving price increases. So why has it been so difficult to rally voters around cracking down on corporate profiteering? Perhaps, as Barry Lynn recently wrote, the problem is a lack of an overarching narrative. Or, as The Lever’s Andrew Perez and David Sirota note, it is a simple matter of Democrats not trying all that much. But it could also be a lack of opportunity: perhaps what has been missing is a story so egregious that it serves as a vivid illustration of how corporate greed exacerbates inflation. After all, every good story requires an attention-grabbing villain.

Enter the Kroger-Albertsons merger. If allowed to go through, the $25 billion deal would combine two of America’s largest grocery store chains into a corporate behemoth that would own Ralphs, Dillions, Safeway, Vons, and many others. It is, of course, a terrible idea that seems about as illegal as a merger can get. For one, the supermarket sector is already highly concentrated: the National Grocers Association estimates that over 60 percent of US grocery sales go to the country’s top five retailers. Moreover, merging the second-largest and fourth-largest grocery store chains would leave consumers in many markets with little to no options beyond Kroger-Albertsons and Walmart.

As Forbes’ Errol Schweizer writes in his fantastic analysis of this merger, the deal would potentially be highly lucrative for investors and company executives. But it would be extremely damaging for workers and for consumers, and especially for suppliers:

“A 5,000 store chain in over 48 states could more easily set payment terms, negotiate shelf space and assortment, and extract better costs and greater trade allowances for promotions, couponing, ad placement and slotting fees.”

Not to mention that proposing such a merger as food prices are increasing 13% year over year is a scandal unto itself. To justify this merger, the companies claim that the merged company would have the economies of scale necessary to reduce prices. But as Matt Stoller and others have pointed out, this is a weak argument. Moreover, it’s the exact same argument Albertsons made when it bought Safeway in 2015.

It would be easier to take these claims seriously if the merged company’s prospective CEO did not brag about how they can get away with raising prices by using inflation as a cover. Last year, Kroger CEO Rodney McMullen boasted that “a little bit of inflation is always good in our business” and added that as long as inflation is around 3%-4%, the company could cite it to justify price hikes since “customers don’t overly react to that.” Weeks later, Kroger raised prices, citing inflation as the reason.

Given its peculiar timing, it is no surprise that the merger has already sparked political backlash. Several Democratic Senators, including Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Amy Klobuchar, have come out strongly against the deal. Klobuchar and Republican Senator Mike Lee, the ranking members on the Senate Judiciary’s antitrust subcommittee, plan to hold a hearing on the deal in November.

In other words, it is a merger only a judge could love. While the FTC will almost certainly try to block this deal, Kroger and Albertsons are clearly counting on merger-friendly federal judges to reject these attempts, as they have done several times this year. Anticipating the regulatory backlash, the companies have offered to spin off up to 375 stores to alleviate antitrust concerns. It is easy to see why they would try to appease enforcers this way: it worked for Albertsons when it convinced the FTC to approve the Safeway merger in exchange for selling 168 stores to local chain Haggen. But as David Dayen and Ron Knox point out, that arrangement failed miserably, and Albertsons soon ended up buying many of the stores it sold at a nice discount.

In any case, FTC Chair Lina Khan is unlikely to take the bait. Khan has criticized similar divestitures in the past and has already set her sights on “the anticompetitive practices of large supermarket chains.” Given the judiciary’s long-standing pro-monopoly bias, the companies may be right that the merger could go through. But this merger may just be so preposterous that even the courts would have a hard time waiving it through.

This deal, in other words, is the antitrust equivalent of Liz Truss’s mini-budget: it is deeply unpopular, would be a complete disaster, and can only really appeal to ideological zealots or those paid to advocate for it. So why even attempt it? Stoller theorizes that the whole thing might be an attempt at financial engineering by Albertsons’ private equity investors, Cerberus and Apollo, to squeeze $4 billion from the company as a “special dividend” before the merger is inevitably shot down.

But whether or not the Kroger-Albertsons deal actually goes through, it represents a rare political opportunity. What better way to encapsulate the connection between market power and high food prices than a merger that promises to increase prices and offers no benefit to anyone but private equity investors and executives? Whether Democrats capitalize on this opportunity or not remains to be seen. But if there was ever a merger that could tie it all together, this is it.

Much of economics is based loosely upon principles of physics. Social sciences, seeking street cred as a science, looked toward the hard sciences to improve their standing. Out of all the social sciences, economics perhaps did the best job of conveying the notion that it is a hard science and that its beliefs are actual scientific principles.

In Physics, Efficiency is measured in a CLOSED system

Efficiency in physics measures how much energy is preserved by a system. The greater the preservation of energy, the greater the efficiency of the system. However, most physical processes cannot be reversed, especially those that involve things such as electrical generation or heat. Most energy processes are not fully efficient: In electrical generation, for example, the efficiency of a unit can be measured by its heat rate.

According to Philip Mirowski, the law of conservation of energy prohibits the notion that energy is lost in a system. That is true if the system we are examining is a closed system. The laws of thermodynamics, upon which much of economics is based, assumes a closed system. For example, the first law of Thermodynamics states that energy cannot be created nor destroyed, only transferred in form. That transfer is unidirectional when discussing matters such as combustion. Compare with the notion of Pareto Optimality, in which no situation leads to any improvement without a transfer.

In antitrust, the analysis of conduct is quite distinct from that of physics, as it tends to ignore any losses outside the system.

Antitrust does not examine the entire effect of a merger. Instead, what is examined is the change to a “relevant market,” which is scrutinized to determine injury to consumers within that market. Thus, the merger creates changes in the relevant market only, and only those changes that remain in the market are considered positive or negative. Every other negative change is beyond the scope of examination. As an example, an efficiency to a merger in a relevant market might be massive layoffs. The effect of those layoffs are beyond the scope of antitrust, but may well count as positive for purpose of antitrust analysis.

This notion is not new to economics. Greg Mankiw had a parable related to a heroin addict. He wrote: “In some circumstances, policymakers might choose not to care about consumer surplus because they do not respect the preferences that drive buyer behavior. For example, drug addicts are willing to pay a high price for heroin. Yet we would not say that addicts get a large benefit from being able to buy heroin at a low price (even though addicts might say they do). From the standpoint of society, willingness to pay in this instance is not a good measure of the buyers’ benefit, and consumer surplus is not a good measure of economic well-being, because addicts are not looking after their own best interests.”

Mankiw’s point might be dismissed as a concern about a rationality failure in one particular market (the market for heroin). However, we could instill a different hypothetical here and reach the same result. Assume a single-product economy that produces widgets. Every worker is employed in producing widgets. A merger takes place, and two of the companies become more efficient by laying off workers. Fewer consumers of widgets means less demand, which in turn begets more mergers, laying off more workers. In such a situation, what is occurring is a wealth transfer.

However, because it is all internalized into one market, it should be a wealth transfer that antitrust cares about. It does not. Agencies would consider the layoffs efficient, no matter that the ultimate result would be collapse of the economy, because it only looks at one merger at a time without regard to follow-on mergers. The hypothetical here would be an approximation of a “closed system,” one in which there is no change in energy. Even here, however, there is loss in the sense of the workers who are lost to the system. It is possible that antitrust enforcers might start to care at around a “3 to 2” merger, but by that point it is far too late.

To those who might suggest my example ignores the perils of buyer power, again, antitrust would likely only care when the market moved from 3 to 2. Moreover, it would bring Section 1 wrath about any labor cartel, absent unionization. One might imagine one of the “efficiencies” here would be destruction of the labor movement.

The losses outside of the system of reference (in antitrust the “relevant market)” is something only occasionally analyzed by antitrust, but only for the benefit of merging parties.

One such example is “out of market efficiencies.” As the Commentary to the Guidelines states:

Inextricably linked out-of-market efficiencies, however, can cause the Agencies, in their discretion, not to challenge mergers that would be challenged absent the efficiencies. This circumstance may arise, for example, if a merger presents large procompetitive benefits in a large market and a small anticompetitive problem in another, smaller market.

In other words, even if there is an anticompetitive issue in the relevant market, large enough positive transfers accumulating into another market may trump those anticompetitive effects. Perhaps the best example of this is in the airline industry: A merger that creates monopoly in 13 smaller (rural) routes might not be challenged if it allows the merged airlines to vigorously compete with foreign carriers on international (business) routes.

To some degree, what the Guidelines is endorsing is akin to a wealth transfer that it typically believes to be beyond the scope of its analysis.

A final example of out of system losses are efficiencies in general. As the merger guidelines commentary notes:

Merger-specific, cognizable efficiencies are most likely to make a difference in the Agencies’ enforcement decisions when the efficiencies can be expected to result in direct, short-term, procompetitive price effects. Economic analysis teaches that price reductions are expected when efficiencies reduce the merged firm’s marginal costs, i.e., costs associated with producing one additional unit of each of its products. By contrast, reductions in fixed costs—costs that do not change in the short-run with changes in output rates—typically are not expected to lead to immediate price effects and hence to benefit consumers in the short term. Instead, the immediate benefits of lower fixed costs (e.g., most reductions in overhead, management, or administrative costs) usually accrue to firm profits.

These costs are typically labor costs. As such, the job losses create drags on local economies.

In Physics, transfers are often unidirectional and cannot be undone.

The second law of Thermodynamics states that the entropy of any isolated system (the unavailability of a system’s thermal energy for conversion into mechanical work) always increases. In terms of unidirectional movement, this means that “a system can only be oriented in one direction in time precisely because it cannot go back the way it came, if its path involved the dissipation of heat.” In other words, most system decisions are not reversible.

For antitrust, this would mean the processes of concentration cannot be undone in the way that neoclassical economics envisions. As Mirowski points out, this is a serious issue for economics.

Moreover, serious consideration of the notion of irreversibility would clash with the dictum that the market can effectively undo whatever man has wrought. Finally, and most pertinently from the vantage point of a discipline seeking to emulate physics, the concept of energy in thermodynamics is thoroughly unpalatable when cooked down into the parallel concept of utility in neoclassical economic theory. For example, the parallel would dictate that utility/value should grow more diffuse or inaccessible over time, a figure of speech possessing no plausible allure for the neoclassical research program.

This would suggest that allowing a market to concentrate would be incredibly difficult to undo. In other words, Type II errors are very serious because they are not undoable. This comes as no surprise to antitrust enforcers, who are always concerned about post-merger remedies. It is impossible to unscramble the eggs.

Physicists know what they are seeking to measure

I pause here only to recognize that there is a problem of WHAT is to be measured in markets. Much work has been done on the measurement problem in social sciences. Such a discussion would be the basis of its own post. Measurement problems abound not only because of the inability to make interpersonal comparisons of the utility consumers receive from consumption but also in terms of productive efficiency. As Mirowski states:

The metrics of the efficiency of inputs in a production process are rarely identical with the units in which the commodities are bought and sold. Oil is sold by the barrel, but its efficiency as an input depends on its BTU rating, or perhaps its sulfur content in milligrams per liter, or its Reynolds number, and so on. Further, this metric will vary from process to process, even if one is looking at the same barrel of oil….Such distinctions are critical for any serious representation of a production field, because they raise the possibility that, as long as the axes of the field formalism are confined to commodity space, the field cannot be analytically defined….We hasten to add that this entire discussion is a disquisition on the problems of neoclassical economic theorists, and not the practical actors in the actual economy. They do not separate their world into airtight divisions of substitution versus innovation; nor do they keep tabs on marginal products (unless they have been to business school); nor do they have difficulty keeping track of the boundaries of their economic activities. Instead, they actively constitute the identity of their economic roles and artifacts as they go along.

The problem is exacerbated in antitrust if Professor Herb Hovenkamp is correct and consumer welfare means more than one thing.

Incomplete Measurement Favors Concentration and Externalization of Economic Injuries

Thus, that to which antitrust enforcement agencies apply the notion, the “relevant market,” is not a closed system. A firm claims efficiencies, typically expressed by an economist making over $1000 an hour, it typically means job loss, layoffs, and the foisting of costs outside the system of examination. This is what Professor E.K. Hunt called the “invisible foot:”

The “invisible foot” ensures us that in a free-market . . . economy each person pursuing only his own good will automatically, and most efficiently, do his part in maximizing the general public misery. . . . To paraphrase a well-known precursor of this theory: Every individual necessarily labors to render the annual external costs of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public misery nor knows how much he is promoting it. He intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible foot to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it any better for society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes social misery more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

In other words, market transactions promote pervasive negative externalities. In examining only the relevant market and consumer welfare, the Antitrust Enforcement agencies are assuring they ignore effects foisted upon the remainder of the economy, the externalization of costs associated with the merged firms’ transaction. Those negative externalities are also considered efficiencies within the relevant market, and their exportation outside of the market is considered a value-less transaction. It could be the case that the positive effects inside the system are outweighed by the negative effects outside the system as those effects are externalized. It could be the case as well that the positive effects are overestimated, as might be the case in a merger claiming efficiencies of system integration that take 4 times longer than projected.

Consumer Welfare Theory isn’t Science—It’s A Policy (an Ethical Consideration)

If one changes the lens back to physics, the framework of analysis would be considered wrong because there cannot be loss of energy to the system. Thus, the focal point of the analysis is always a singular framework that tends to benefit the merging parties except in the most extreme cases. Thus, the “science of antitrust economics” is incomplete, because it disclaims losses to the system without further analysis. By focusing on consumer welfare in one relevant market, it assures a most narrow antitrust goal that in effect assures a large externalization of costs. Indeed, it solicits it. As an example, the consideration of out-of-market efficiencies without any consideration of out-of-market costs is indefensible outside of some ethical argument in favor of consolidation.

Efficiency in physics is a valueless concept, the purpose of which is to describe as the work performed per quantity of energy. It is the maximization of something to be measured, output, subject to the amount of input available. It is examined on a system basis. It is not a position of advocacy. Nor is it identical to the view economists have of the term.