Antitrust restructuring of major corporations is on the table in a way it has not been since the Microsoft case in the late 1990s. Indeed, the historic moment may be comparable to the breakup of Standard Oil in the 1910s and AT&T in the 1980s, when courts reorganized those companies and freed the market from their control. Today, judges face a similar opportunity to rein in today’s rapacious monopolists.

Amid rising public pressure to challenge concentrated corporate power, the federal government has, since 2020, filed antitrust lawsuits against Google, Amazon, Meta, and Apple, as well as dominant firms in the agriculture, debit payment, and rental pricing software industries. These cases aim to break monopolistic control of markets, and not merely to stop unfair practices. The outcome of this litigation wave will determine whether antitrust remains a meaningful check on concentrated private power or operates as regulatory theater.

Antitrust enforcers stand poised to secure favorable judgments in lawsuits that affect multiple sectors of the economy. These lawsuits could bolster farmers’ ability to repair their equipment, reduce the costs retailers incur on e-commerce platforms, increase the revenue software developers earn from their smartphone applications, and reduce the interchange fees businesses must pay to credit and debit card companies.

The poster child for the burgeoning possibilities of antitrust remedies involves the lawsuits against Google. In August 2024, Judge Amit Mehta ruled that Google was liable for monopolizing the search market. He found that Google illegally paid Apple and other manufacturers billions of dollars every year to be the default search provider in web browsers on desktops and smartphones, resulting in the foreclosure of critical distribution channels to competitors. In April 2025, Judge Leonie Brinkema held that Google was liable for monopolizing the ad-tech market, which produces the revenue stream that underpins much of our modern media system. In her decision, she found Google used its dominant control over digital advertising to lock in news publishers, impose supra-competitive take rates on Google’s exchange, and exclude competing digital advertising providers.

Other lawsuits against Google, such as the widely publicized lawsuit by game developer Epic Games, have also found Google liable for monopolization. Given this legal onslaught against Google, odds are in favor that the corporation will undergo some form of corporate restructuring. Due to Google’s immense size and scale, the result would fundamentally alter how the public uses and accesses the internet. Breaking up Google—by divesting Chrome or its digital advertising business—would strip the corporation of its control over access to information and online revenue. The shift would mean more competition, the viability of privacy-oriented alternatives, and greater power for journalists, creators, and users concerning how information is distributed and monetized.

A few federal judges and Gail Slater, the Assistant Attorney General for the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, will control the scope of the remedies to be imposed on Google. Regardless of any obstacles the DOJ staff may face in determining which remedies they should pursue, one thing is certain: federal judges are vested with all the authority they need to impose the government’s demands, and they are obligated to impose sweeping remedies on antitrust violators like Google.

Flexing the Structural Relief Muscle

Remedies convert violations of legal rights into actionable consequences. In his leading casebook, renowned remedies scholar Douglas Laycock succinctly asserted that “remedies give meaning to obligations imposed by the rest of the substantive law.” In other words, remedies are how democratic institutions prove their legitimacy: equipping the law with real force to answer public calls for action, rather than serving as a meaningless political gesture. Without effective remedies, the law merely functions as a speed limit sign with no police or cameras to enforce it.

The antitrust laws are, in the words of Senator John Sherman, namesake of the titular Sherman Act, “remedial statute[s].” To accompany the sweeping prohibitions on “restraints of trade” and monopolization, lawmakers were diligent to buttress these proscriptions with a panoply of robust remedial provisions.

The antitrust laws include the ability for harmed private parties to obtain treble damages and attorneys’ fees (a novel feature in American law at the time of their enactment). Lawmakers authorized federal, state, and private enforcers to initiate lawsuits, eventually establishing two separate agencies to advance the cause. Further supporting these profound legal tools were the equity provisions that empowered enforcers to seek and, critically, courts to impose structural changes to a business’s operations. The purpose of this vast and deep remedial landscape was to facilitate the “high purpose of enforcing the antitrust law[s].”

At the federal level, the thinking surrounding the purpose and necessary goals of antitrust remedies has been lost for some time. With the notable exception of the antitrust litigation against Microsoft in the late 1990s, market restructuring has simply not been seriously contemplated by enforcers since the 1970s, when the DOJ was litigating its antitrust lawsuit against telecommunications giant AT&T for willfully stifling competition in, among others, long-distance services. According to historian Steve Coll’s book The Deal of the Century, the prospect of breaking up AT&T and imposing other remedies permeated the government’s legal strategy.

After the breakup of AT&T, however, in concert with the purposeful decline in federal antitrust enforcement, the intellectual and institutional muscles supporting ambitious remedies quickly atrophied. Decades of underenforcement drained both the doctrinal imagination and the human talent needed to design and implement structural relief.

For the federal government, a new opportunity to implement robust structural remedies almost presented itself in its lawsuit against Microsoft in the late 1990s. A structural breakup was interrupted, however, due to improper judicial conduct and changes in political administrations. Enforcers ultimately abandoned a breakup in favor of paltry restrictions on Microsoft’s business practices. Subsequent academic literature criticized the handling of the lawsuit for the lack of critical thinking regarding the remedies that enforcers wanted. Not since the antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft has another opportunity of similar magnitude presented itself to federal enforcers.

A New Opportunity Arises

Now, more than a quarter century later, the public has another chance to witness the full thrust and potential of the antitrust laws. What is critical is that enforcers and judges need to be reminded that restructuring businesses to restore competitive conditions and prohibiting dominant corporations, like Google, from engaging in unlawful behavior has always been at the heart of what the antitrust laws can and must do.

In one sense, the ability to restructure the economy provides the clearest visible indicator to the public that justice has been served. For too long, the public has witnessed instance after instance of corporations engaging in often blatant lawbreaking and walking away with no more than token penalties, accompanied by the boilerplate legal phrase “this is not an admission of guilt” on the settlement form.

It’s no secret that the public’s confidence in our political system was shattered after the 2008 financial crisis, when only one low-level bank manager was jailed, and the biggest financial institutions only got bigger. Meanwhile, President Obama refused to use his executive authority to prevent millions of Americans from losing their homes and livelihoods. The precipitous collapse of white-collar crime prosecution after 2012 only intensified this perception of corporate impunity, a trend that continues today. It should go without saying that a well-functioning democracy of the kind the antitrust laws were meant to buttress requires punishing wrongdoers.

Structural remedies also bring clarity to the purpose of the antitrust laws. They ensure that corporations are adequately incentivized to and remain subservient to the public, and must adhere to established norms concerning what constitutes lawful means of operating in the marketplace. Remedies, in this sense, serve dual purposes: they deter future violations and, when applied to offenders, reinforce institutional legitimacy by ensuring meaningful consequences rather than merely symbolic fixes.

None of this was accidental. Congress wrote the antitrust laws with ambition. In both the statute’s text and its legislative history, Congress codified deeply held moral and ethical norms, grounded in principles of fair competition, non-domination, and democratic control of the economy. To facilitate these principles, Congress gave the public the tools for broad economic reordering in the event of a violation. It was the Supreme Court’s ideological shift, which began in the late 1970s and was subsequently adopted by the Reagan administration in 1981, that neutered the institutional will to enforce and interpret the laws as Congress intended. Nevertheless, once liability is established, structural change is not merely justified by law—it is mandated by it. Indeed, the Supreme Court has been uncharacteristically clear that liability obligates, not just authorizes, the courts to impose structural change.

In a decision from 1944, the Supreme Court stated, “The Court has quite consistently recognized…[d]issolution[s]…will be ordered where the creation of the combination is itself the violation.” In another decision, the Court opined about the absurdity that would arise if weak remedies were imposed on antitrust lawbreakers. “Such a course,” the Court stated, “would make enforcement of the Act a futile thing[.]” In another decision, the Supreme Court stated that “[c]ourts are authorized, indeed required, to decree relief effective to redress the violations, whatever the adverse effect of such a decree on private interests.” The jurisprudence is replete with many more judicial directives commanding the lower courts to impose sweeping remedies to effectuate Congress’s legislative command.

Not only is there a duty to impose structural remedies, but the Supreme Court has been straightforward that in all but the most wholly unwarranted situations, a district court judge—like Judge Mehta or Judge Brinkema presiding over their respective lawsuits against Google—is afforded broad discretion on what remedy to impose both to “avoid a recurrence of the violation and to eliminate its consequences.” As long as the remedy is a “reasonable method of eliminating the consequences of the illegal conduct,” judges operate with expansive discretion and face virtually no doctrinal constraints on what can be ordered.

If the desired outcomes are realized, a breakup of Google could fundamentally reorganize the structure of the internet and our experience with it. Requiring Google to spin off its digital advertising platform could enable journalists and content creators to diversify their revenue sources through new competitors, giving them greater autonomy over their income. Divestiture could also enable them to have more control over the distribution of their work products and reduce the constant risk of censorship and algorithmic manipulation that Google has deployed to maintain its monopoly over search and advertising. Moreover, a spinoff could also erode the surveillance advertising model, making privacy-friendly alternatives more viable competitors. For the public, more competition in search could expand options for finding and presenting information on the internet. Likewise, a divestiture of Google’s Chrome browser could open new pathways to access the internet and lessen dependence on a single dominant provider.

Corporate Allies Spring into Action

In an attempt to get ahead of the litigation game, executives and ideological friends in the legal academy have churned out scholarship and opinion pieces designed to deter enforcers and courts from imposing remedies deemed “too harsh” to Google’s operations. In a recent paper on structural remedies, Professor Herbert Hovenkamp, a leading establishment antitrust scholar (and a Big Tech sympathizer), provided a hierarchical schematic outlining how remedies should be considered and administered. One of his points stated that “Even with market dominance established, alternatives to structural relief are often superior, and simple injunctions are often best; for any problem, they should be the first place to look.” The International Center for Law and Economics, a member of Google’s “army of paid allies,” submitted an amicus brief to the district court overseeing Google’s antitrust lawsuit, erroneously stating that “structural remedies are disfavored in Section 2 cases[.]”

Naturally, too, Google’s business executives have ardently defended the company’s business practices. In April 2025, Google’s CEO Sundar Pichai testified that any breakup of Google would be “so far-reaching” that it would be a “de facto divestiture” of its search engine. Pichai also decried the forced sharing of the data that underpins Google’s search engine as a remedy that would leave the company with no value. It is revealing to hear the highest-ranking corporate executive at the company admit that Google’s success is dependent on a select few unlawful practices, rather than its business acumen, and that Google is apparently incapable of deploying lawful methods of competition to succeed in the marketplace. Since the filing of both federal lawsuits, Pichai has also embarked on a marketing tour to tout the company’s operations, defend the benefits of its business practices, and detail the potential unintended consequences of the government’s lawsuits. Such alarmism is a standard defensive tactic, deployed to influence judges and sap public support for real solutions.

But from the earliest days of antitrust law, the Supreme Court has consistently affirmed that breakups, divestitures, and other corporate restructuring remedies—though often described as “harsh,” “severe,” or inconvenient by violators—are time-tested, necessary, and appropriate for restoring competitive market conditions. In a forthright statement, the Court stated that antitrust litigation would be “a futile exercise if the [plaintiff] proves a violation but fails to secure a remedy adequate to redress it.” In fact, the Court has lamented that prohibitions on specific conduct—rather than breakups or other corporate reorganizations—are “cumbersome,” delay relief, and position the court to operate in a manner for which it is “ill suited.”

Rising to Meet the Moment

The vigorous enforcement of the antitrust laws in the post-World War II era compared with the drastic decline that began in the late 1970s is clear evidence of the changing “political judgment” (as Professors Andrew Gavil and Harry First call it) concerning what remedies should be imposed. Judges today are far different from their historical counterparts, who viewed antitrust as a facilitator of economic liberty, a bulwark against oligarchy, and fundamental to protecting our democracy. Punishing antitrust violators was not just a legal formality but also a moral imperative.

Even though many judges have not considered these issues in decades—or, in some cases, ever in their careers—during this profoundly important moment in American history, judges should be cognizant of what the jurisprudence plainly mandates them to do. If the rule of law retains any meaning, it demands that courts decisively address the harms the government has been litigating for a half-decade.

The question now is not whether courts can impose structural remedies; it is clear they can. It is whether they will rise to meet the moment. The remedies that judges will impose on Google and the other alleged monopolists in the government’s lawsuits will be a defining test of judicial integrity and democratic accountability to the rule of law. A failure to act calls into question the very legitimacy of our legal system to hold the powerful accountable. As the jurisprudence makes clear, anything less than structural relief results in the public “[winning] a lawsuit and [losing] a cause.”

Daniel A. Hanley is Senior Legal Analyst at the Open Markets Institute.

On December 3, 2024, Chris Salinas officially entered a nightmare that would make Freddy Krueger proud—a nightmare in the medical industry known as prior authorization. Even I, as his gastroenterologist, didn’t know at the time that this one would become my biggest nightmare yet. Chris has given me permission to share the details of his experience, including his medical ailments.

Chris has ulcerative colitis, a chronic autoimmune disease of the colon that can cause flares of bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue, among many other symptoms. I have been treating Chris and his ulcerative colitis for over 15 years. Over those years, for various reasons, he had ultimately failed multiple medications for his illness. By December of last year, the next one we wanted to try was Entyvio, a drug under patent approved by the FDA for ulcerative colitis in 2014. Entyvio is considered in the industry a “specialty pharmacy” drug. In theory, nobody in the industry knows exactly what that means. In practice, what it means is big money, the money that pays for all those ads you see on TV for Ozempic, Wegovy, Skyrizi, and the like (rule of thumb: if the brand has a “z” or “v” or “y” in the name, it’s likely a moneymaking specialty drug). And in practice, what it meant for Chris and me is that I needed to get prior authorization for approval of Entyvio.

Just the phrase “prior authorization” sends a chill down every physician’s spine. On its face, prior authorization has a functional purpose: to control utilizing drugs that can be quite costly for a health plan to cover. Yet imagine your worst call climbing up the giant sequoia of customer service phone-trees. A call for a prior authorization is worse.

You think I’m exaggerating? Every year the American Medical Association conducts a nationwide survey of a 1,000 practicing physicians on prior authorization. In 2024, 40 percent of physicians had staff who worked exclusively on prior authorizations and spent 13 hours weekly on them; 75 percent reported that denials of prior authorizations had increased; 80 percent didn’t always appeal the denials, due to past failures or time constraints. And almost 90 percent of physicians reported burning out from the process. I know physicians who closed down their practices and retired early solely because of prior authorization.

According to the survey, the impact on patient care is no less nightmarish. Nearly 100 percent of physicians felt that prior authorization negatively affected patient outcomes; 23 percent noted that it led to a patient’s hospitalization; 18 percent said it led to a life-threatening event; and 8 percent said it led to permanent dysfunction or death. Fortunately, Chris wasn’t at death’s door. But even with a philosophical approach that most of the time in medicine, less is more, I felt that getting on Entyvio was Chris’s best shot at improving his quality of life, free of the extended flare of ulcerative colitis he was enduring.

So last December, I called Express Scripts, Inc. (“ESI”) to get the prior authorization for Entyvio. ESI is the pharmacy benefit manager (“PBM”) of Chris’s employer-based health plan. For those who haven’t studied the FTC’s damning 2024 interim report on the industry (“FTC report”), PBMs serve as the middlemen between the pharmacies that dispense drugs, the manufacturers that make them, and the government/employers/insurance plans that pay for them. I gave ESI all the required clinical information for approval of both the initial intermittent intravenous infusions for the first six weeks and the subsequent biweekly maintenance injections Chris would be giving to himself subcutaneously. As Chris had by then failed multiple other therapies, it was a relatively easy call for ESI to grant the prior authorization for Entyvio. I then called in both the intravenous and subcutaneous Entyvio prescriptions to Accredo, the administering specialty pharmacy, who assured me that we were good to go.

We were not good to go. At first, Accredo told me that Chris could get the infusions at home through a service set up by Accredo. Then it told me it couldn’t. Then it told me it would find a local infusion center to administer the drug. Then it told me I had to find one. At every twist and turn, I had to initiate the call to Accredo to find out why the infusions hadn’t started. So did Chris, who said about his Accredo calls: “There were many circular conversations where it just went nowhere. Every time they would tell me, you have to give us a week and then call us back; and then when I call them back, it’s just like starting the process over again. And then again, and again, and again.”

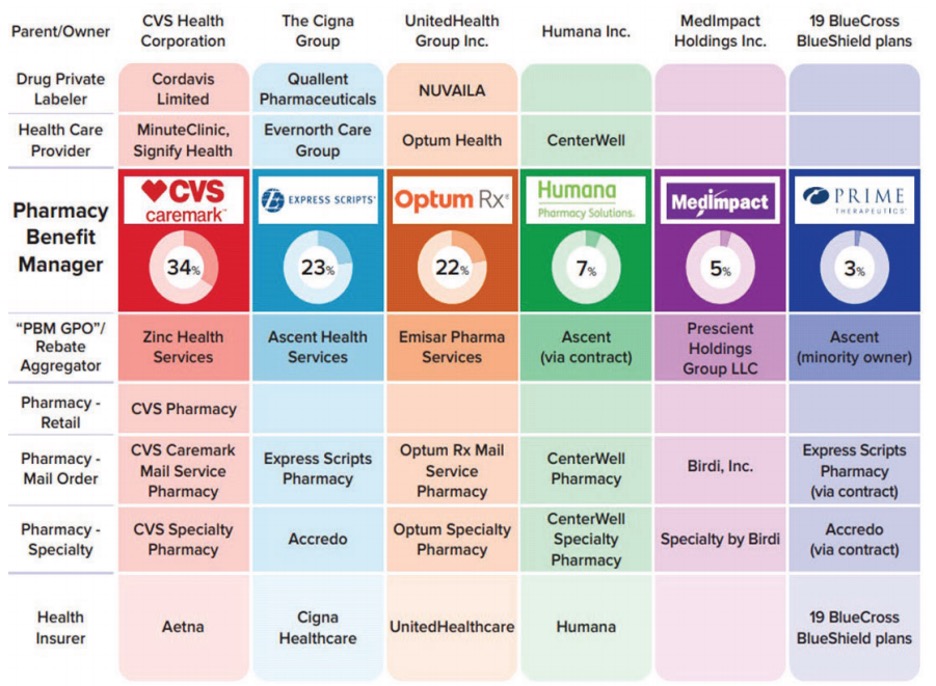

The breakdown in the prior authorization process that Chris and I were weathering is an endemic breakdown in healthcare quality. That breakdown in quality is the result of the incredible horizontal concentration and vertical integration the last few decades have wreaked in the healthcare industry. This chart from the same FTC report tells the tale.

ESI appears in the second column under The Cigna Group, as the associated PBM. The 23 percent below its name indicates that ESI controls 23 percent of all prescriptions filled in the United States.

On horizontal concentration overall, the three biggest PBMs—CVS Caremark, ESI, and Optum Rx, manage nearly 80 percent of all prescriptions filled in the United States; in terms of the standard Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) measurement of horizontal concentration, the mean HHIs were pushing 4,000 and climbing in state and local geographic markets.

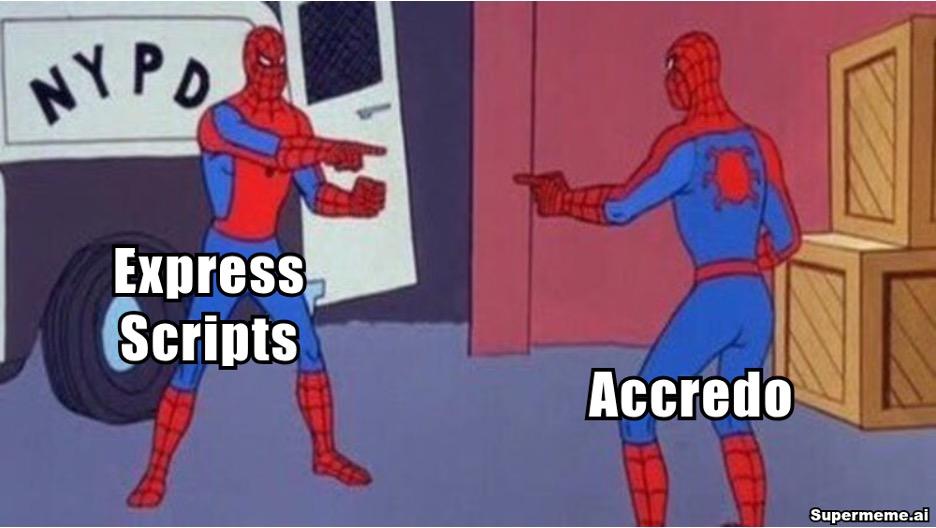

On vertical integration, the three biggest PBMs are owned by the three of the five biggest health insurance companies in America—CVS Caremark under Aetna, ESI under Cigna, and Optum Rx under United. The vertical integration doesn’t stop there: the healthcare conglomerates that own the biggest PBMs also increasingly own private labelers that manufacture the drugs, the providers who prescribe them, and the pharmacies that dispense them. This includes Accredo, the specialty pharmacy owned by Cigna—which owns ESI, the PBM!

To any reasonable person thinking through the inevitable conflicts of interest, beware. Your head may eventually explode—for which you’ll probably need a prior authorization for something. The FTC report catalogs many of the adverse effects of horizontal concentration and vertical integration involving PBMs: (1) excluding generic drugs from formularies in exchange for higher pay-to-play “rebates” from the manufacturers; (2) recasting group purchasing organizations into rebate aggregators, often headquartered offshore, that still enjoy safe harbor from anti-kickback law; (3) steering patients exclusively to the conglomerates’ own PBMs and specialty pharmacies while crowding out independent pharmacies, especially when high-profit specialty drugs are involved; (4) turning contracts with independent pharmacies that have little bargaining position effectively into opaque adhesion contracts with “clawbacks” that make it possible for the pharmacies even to lose money, in the end, from a sale; and (5) abusing prior authorization and other utilization management tools to preference the conglomerates’ financial interests over the patients’ best interests.

The FTC report was criticized by a dissenting Commissioner (Holyoak) for being prematurely released without “rational, evidence-based research” to show that horizontal concentration and vertical integration of PBMs raised consumer prices. Accordingly, in 2025, the FTC expanded on its 2024 report, by analyzing additional data received from PBMs, to show that significant markups on numerous specialty generic drugs—some exceeding 1,000 percent—made PBMs and their affiliated specialty pharmacies huge revenues. That, it followed, cost government and commercial plan sponsors significantly more money, along with the subscribers/patients who shared the increasing costs.

Likely backroom political gamesmanship notwithstanding, the FTC should be praised and pushed to continue focusing on the effect of PBM consolidation on consumer drug prices. But with the focus on consumer prices, neither the 2024 interim report, nor its dissent, nor the 2025 update fully captures why horizontal concentration and vertical integration of PBMs are so bad for healthcare. Take it from an on-the-ground, practicing physician who has been at bedside, for over a quarter-century, observing policymakers afflicted with an evidence-enslaved (rather than evidence-informed) econometrics delirium rotting the core of what matters in healthcare.

It’s not just the price effects—it’s also the quality! Horizontal concentration and vertical integration of PBMs, and healthcare at large, are destroying quality in healthcare. Surely the FTC is aware of these non-price effects, as the over 1,200 public comments received by the FTC on PBMs’ business practices likely revealed. The 2023 Merger Guidelines published jointly by the FTC and the DOJ emphasized the same, adding a “T” to the end of the “SSNIP” of the Hypothetical Monopolist Test: “A SSNIPT may entail worsening terms along any dimension of competition, including price (SSNIP), but also other terms (broadly defined) such as quality, service, capacity investment, choice of product variety or features, or innovative effort.”

Yes, SSNIPTs may be harder to quantify than SSNIPs. But when it comes to PBMs, SSNIPTs galore smack you in the face.

Many phone calls later, and over a month after ESI had granted the prior authorization of Entyvio, Chris finally received his first of three infusions. It cost him around $300. He was then told the second infusion would cost him $1,800. That triggered another set of phone calls involving Accredo, with Chris noting, “They kept telling me that my insurance company denied [the Entyvio], and I said no, my insurance company did not deny it . . . I was actually getting ready to write an $1,800 check.” Fortunately, as Chris explained, the pharmacy and PBM then found the co-pay assistance program information Chris had sent, which they had apparently misplaced. The price of his second and third infusions? Five dollars each.

Chris’s ulcerative colitis symptoms responded well to the Entyvio infusions. But the healthcare nightmare wasn’t over. Chris was supposed to transition to the subcutaneous Entyvio shots in late April, eight weeks after his last infusion. When he called Accredo in March to confirm, he was told that Accredo didn’t have the prescription for the shots. I then called Accredo and was told the opposite. Chris then called and learned that Accredo had two accounts in his name, one of which was dormant (supposedly from the change of calendar year) and where the prescription was hiding. Accredo assured him that it would merge the accounts, and all would be good. Chris called again a couple of days later, when Accredo told him it was waiting on approval from his insurance company—even though the Entyvio had already been approved. More phone calls the following week, and the prescription was lost again because the accounts had not in fact been merged. Late April came and went, with no continuation of drug.

Chris estimates that between March and May, he made over 20 phone calls to Accredo. During the lapse in treatment, his cramps, diarrhea, and urgency returned. “In the meantime, I’m having to deal with my diagnosis . . . which is not fun, right? I’m having to kind of manage my travel that I do for work around that situation, which is difficult. And it’s a lot of stress . . . being on airplanes and all that kind of stuff.” It was a lot of stress for me as well, knowing that the longer Chris was off Entyvio, the more potential he would have to develop antibodies to the drug that would render it ineffective when resumed.

It all came to a head on May 21, a month after Chris was supposed to start the Entyvio shots. I spoke to Paul at Accredo, then Jeanine at ESI, then Mark, Jeanine’s supervisor, while I made Paul stay on the line. ESI informed me for the first time that a fax was allegedly sent to me on January 3 denying the prior authorization for the subcutaneous Entyvio. When asked whether it had sent the denial by regular mail, ESI said no. The reason for the denial? According to ESI, I had not answered some clinical criteria question—a question I had certainly answered when the infusions and injections were initially approved back in December. When I insisted on clearing up this nonsense once and for all over the phone, ESI informed me that a policy change beginning in 2025 had eliminated approvals over the phone; they could only be done via fax. The very tech that had failed us in communication of the purported denial. All this, with ESI, as a PBM in the business of administering healthcare, knowing full well the impact this was having on Chris’s health.

I finally demanded to speak to a peer, for a peer-to-peer review. In 2024 and 2025, that no longer means a gastroenterologist, or even a medical doctor, but often a nurse or pharmacist. No offense to nurses or pharmacists; they are sacred to healthcare. But when it comes to prior authorization for a specialty drug like Entyvio, they are not my peers. Nonetheless, the peer here was a pharmacist named Stefan—the first person at ESI I felt wasn’t carbon-based AI. He acknowledged the injustice of the situation but said my only recourse was to fax clinical information again to seek approval.

And then, magically out of the blue . . . Stefan said he found some “override” to approve the subcutaneous Entyvio. Just like that, a personal-record-breaking two hours and 45 minutes into the call, the prior authorization was over.

I give you all these gory details (believe it or not, with many left out) not to be melodramatic, but because when it comes to going through the prior authorization gauntlet with these highly concentrated, vertically integrated PBMs, this is now the norm, not the exception. As chronicled in the public comment by the American Economic Liberties Project, past lapses in enforcement by the FTC and DOJ created these consolidated beasts. And if you download the appendices of that comment, you will read one similarly abominable experience after another sampled from anti-PBM Facebook groups with names like “DOWN WITH Express Scripts and Accredo!”. On the Better Business Bureau website, ESI has a 1.03/5-star rating, with 1,555 complaints in the last three years. Other PBMs fare no better. In other words, horrible quality is a feature, not a bug, of the biggest PBMs and the healthcare conglomerates who own them—and own you, should you be dependent on them. In the words of former FTC chair Lina Khan, these PBMs have become “too big to care.”

Cory Doctorow says it best: “Enshittification is a choice.” He was talking about Google search. But he may as well have been talking about too-big-to-care healthcare. The lobbyist arm of the big insurance companies recently took notice of their “enshittification” and vowed to simplify prior authorization. But insurance companies have vowed that before, in 2018 and again in 2023.

I’m a GI doctor. I know good shit from bull. And now Chris does as well. I asked him how he would clean it up. “I have to go through [ESI and Accredo],” he lamented, “because of the plan that I’m on with my company, right? But if I had the choice because of customer service, I’d never deal with them again . . . I think that people aren’t looked at anymore as patients; they’re looked at as a business. There’s no personal side to it.”

Chris wants choice in healthcare. The only way he’ll get choice—and not the choice PBMs have made over and over again—is to break these behemoths up. Only then will these companies have skin in the game again and have to compete for customer loyalties. And only then will we renew the “care” in healthcare.

Venu Julapalli is a practicing gastroenterologist and recent graduate of the University of Houston Law Center.

There is much discussion about what Hal Singer has dubbed “Gangster Antitrust,” the extraction of payments, bribes, or other concessions to allow passage of an otherwise anticompetitive merger. Gangster Antitrust can also take the form of conditioning the approval of a procompetitive merger on a seemingly unrelated remedy that advances the political interests of the administration. “Nice merger—be a shame if anything happened to it!”

David Dayen of the American Prospect correctly wrote that there is a law that is supposed to prevent such skullduggery, the Tunney Act, to assure that consent decrees by the Department of Justice (DOJ) are in the “public interest.” The Tunney Act of 1974 was drafted to prevent judicial “rubber stamping” of consent decrees. As explained here, the Tunney Act and its 2004 amendment, prohibiting continued judicial rubber stamping, have yielded just more vigorous rubber stamping.

I’ve written on the Tunney Act twice before, once with John J. Flynn, who happened to assist in its drafting, about the misuse of the Tunney Act in the Microsoft cases to compel the district court to accept a weakened settlement. I wrote a second time, after the D.C. Circuit continued to engage in activist and blatant disregard for the 2004 Tunney Act amendment.

Unfortunately, the Tunney Act’s purpose has been stifled by D.C. Circuit caselaw, and even the Act’s most fundamental purpose of destroying corruption has been neutered.

A brief history of the Act

The Tunney Act, named after Senator John V. Tunney, emerged from scandal surrounding backroom dealings to settle a DOJ merger challenge. It first became a major issue during hearings on Richard Kleindienst’s nomination to be attorney general. Senator Tunney expressed outrage at such closed-door discussions.

In 1969, the DOJ sued to prevent ITT’s acquisition of three companies under Section 7 of the Clayton Act. The DOJ lost two of the three suits. In 1971, the DOJ and ITT agreed to a settlement of the remaining suit. ITT was allowed to retain Hartford Fire Insurance Company but was required to divest several Hartford subsidiaries. The DOJ made no public statement as to the underlying reasons for the settlement. Instead, as was common practice at the time, only the proposed decree was made public.

Two significant events occurred that made people suspicious. First, President Nixon nominated Richard Kleindienst to be attorney general. Kleindienst had been involved in the ITT litigation in his capacity as deputy attorney general, and questions arose concerning his participation in the settlement of the case. Second, ITT offered to help finance the 1972 Republican National Convention. While no quid pro quo was proven, the appearance of impropriety sparked significant debate. (If you want to hear President Nixon ordering a DOJ official to back off the merger, you can listen here.)

Moreover, Kleindienst’s confirmation hearings revealed to the public for the first time the underlying rationale for the DOJ settlement with ITT: Kleindienst asserted that one reason for the settlement was DOJ fear that divestiture would cause ITT’s stock price to fall, causing hardship to shareholders. Another DOJ concern was apparently that the plummeting stock price would ripple throughout the U.S. economy.

All of this seems tame by today’s standards. But at the time, it was a massive scandal. The Supreme Court typically deferred to the DOJ traditionally with respect to consent decrees.

How the Act lost its teeth

Despite the Tunney Act’s prohibition against rubber-stamping, with rare exception, courts have continued to serve as rubber stamps, and the D.C. Circuit caselaw has played an important role in the rubber stamping. The basic standard laid out by the D.C. Circuit appears in the first Microsoft case, in which Judge Sporkin rejected the DOJ’s mealy-mouthed remedies (and eventually led to Microsoft II). The D.C. Circuit wrote:

A decree, even entered as a pretrial settlement, is a judicial act, and therefore the district judge is not obliged to accept one that, on its face and even after government explanation, appears to make a mockery of judicial power. Short of that eventuality, the Tunney Act cannot be interpreted as an authorization for a district judge to assume the role of Attorney General.

Subsequent cases in the D.C. Circuit cling to this standard to assure that courts don’t bother with the “public interest” determination.

Congress reacted, and in 2004 changed the Tunney Act to compel a public interest determination. The legislative history expressly and in detail decried the D.C. Circuit’s caselaw (and cited my work with John Flynn, thank you very much).

The D.C. Circuit and its district courts flat out ignored the amendment, choosing to resurrect its “mockery of judicial function standard.” As the D.C. Circuit explained in a 2016 Speedy Trial Act case:

As we have since explained, we “construed the public interest inquiry” under the Tunney Act “narrowly” in “part because of the constitutional questions that would be raised if courts were to subject the government’s exercise of its prosecutorial discretion to non-deferential review.” Mass. Sch. of Law at Andover, Inc. v. United States, 118 F.3d 776, 783 (D.C.Cir.1997); see Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 253 (D.C.Cir.2003). The upshot is that the “public interest” language in the Tunney Act, like the “leave of court” authority in Rule 48(a), confers no new power in the courts to scrutinize and countermand the prosecution’s exercise of its traditional authority over charging and enforcement decisions.

The basis of the Court’s decision was a misguided notion that failing to enter a consent decree—inherently a judicial function—trampled the DOJ’s prosecutorial discretion under Separation of Powers. It did not consider that forcing a consent decree down the throat of the court also presented separation-of-powers problems. Nor did the Court explain why it is permissible for courts to reject criminal plea bargains without separation of powers problems, yet they must accept consent decrees for the rich and powerful. And while not all of the cases are in the DC Circuit, the vast majority are, and other circuits rely on DC Circuit caselaw and experience. Only one Tunney Act consent decree rejection. Ever.

So, here we are.

The question arises, then, about what exactly would it take to create a mockery of the judicial function?

We don’t know, quite frankly. There does not appear to be much, if anything, out there to suggest what mockery of the judicial function would look like sufficient to reject a consent decree under the Tunney Act.

Prior deals under Tunney Act review have been rubber stamped

Nothing raises eyebrows with the courts when it comes to the Tunney Act. Consider a couple of examples.

In 2008, the DOJ brought a broad and sweeping complaint against American Airlines’ acquisition of U.S. Airways. But politics played a role, according to Propublica: “People were upset. The displeasure in the room was palpable,” said one attorney who worked on the case. “The staff was building a really good case and was almost entirely left out of the settlement decision.” One of the reasons they might have been upset is that President Barack Obama’s former Chief of Staff was now Mayor of Chicago and advocating for the merger at the White House.

In another airline merger, an attorney representing the merging parties became DAAG after the merger won DOJ approval in August of the same year. Sometimes the revolving door in antitrust just spins just that fast.

Even if the courts did awaken to such questions, there is little interest in doing anything about it. One might claim that Judge Leon did a heroic Tunney Act review in CVS-Aetna, but I do not think that the D.C. Circuit precedent left him in a good position to do anything other than accept the decree.

In other circuits, it is possible (but not likely) for a court to reject a consent decree. For a rare (and non-merger) exception, see U.S. v. SG Interests I, Ltd., 2012 WL 6196131 (unpublished opinion rejecting entry of consent decree in a Sherman Act Section 1 collusive bidding case as settling the case for nothing more than “nuisance value”).

Parties have also been known to close deals even before the Tunney Act review has been completed. Judge Leon complained of this practice in CVS-Aetna, but again, the D.C. Circuit caselaw leaves little in the way of judicial action.

Thus, I imagine that courts will continue to do what they have always done—ostrich-like abdication of their powers.

The Tunney Act won’t save civilization, democracy, or even antitrust

Is there a problem with Paramount making a major settlement with Trump and firing Colbert and then having its merger with Skydance approved? We’ll never know, because the courts will only review the complaint, the competitive impact statement, and the proposed final judgment. And rubber stamp.

The HPE-Juniper deal also raises serious questions related to the role of lobbying and whether the DOJ’s acquiescence has precious little to do with separation of powers and prosecutorial discretion and more to do with gangster antitrust. As the Wall Street Journal reported, “Hewlett Packard Enterprise made commitments, not disclosed in court papers, that called for the company to create new jobs at a facility in the U.S., according to people familiar with the matter.” This, if true, ought to be sufficient to reject the consent decree. But I doubt it. While SCOTUS is hard-core killing Chevron and administrative law, it seems totally fine with the extreme level of deference the DOJ gets under the bastardized interpretation of the Tunney Act.

As David Dayen pointed out, there’s a friendly district court judge in the HPE-Juniper matter, who is a former labor lawyer. And both the HPE-Juniper and the UnitedHealth Group-Amedisys matters are outside the D.C. Circuit, which is a reason for hope. Yet other cases have had friendly judges and there are still no cases rejecting a consent decree. And the reason for that is the D.C. Circuit caselaw, regardless of circuit.

How about American Express? According to the Wall Street Journal,

American Express GBT hired Brian Ballard—a longtime Trump backer, who raised $50 million for his 2024 election—to lobby the Justice Department on antitrust issues for the company, according to lobbying disclosure forms. The Justice Department last week dropped a lawsuit it had filed seeking to block American Express GBT’s acquisition of a competitor, CWT Holdings.

This raises another point. The Tunney Act is only involved when we’re dealing with consent decrees with the DOJ. There is zero transparency with respect to merger investigations that have been dropped due to Gangster Antitrust. Decades ago, there was a push for greater transparency for when the DOJ was investigating a matter, and reasoning behind closing a matter without more. That went nowhere, and we are living with the consequences of that as well. And, as administrative law falls for independent agencies like the FTC, there isn’t much to suggest that courts will get in the way of settlements at DOJ’s sister agency, either.

The future looks grim. Sure, Congress reformed the Tunney Act once already. How’d that turn out? And now, it seems unlikely that Congress (in its current sycophantic posture to the Executive Branch) would dare attempt to correct the unbridled power of the Executive Branch to sell out on the cheap or engage in Gangster Antitrust.

The wealthiest man in the world was President Trump’s largest campaign contributor, thirteen billionaires were selected for positions in the administration, and the fourth wealthiest man in the world announced that the third largest newspaper in the country would no longer publish any opinion pieces critical of free markets. As if this weren’t an already alarming indication of the dangerous connection between economic might and socio-political power, next year, the Supreme Court will hear National Republican Senatorial Committee, et al. v. Federal Election Commission, et al., a case with the potential to erode some of the last remaining campaign finance limits. If the Court embraces the petitioners’ argument that broad categories of political spending should be freed from expenditure limits, it could intensify the transformation of American democracy catalyzed by Citizens United v. FEC and related decisions.

This looming decision arrives amid a broader, heated debate about the relationship between economic concentration and political power. Neo-Brandeisians, concerned with the corrosive effects that “bigness” of dominant firms and concentrated markets may have on democracy, increasingly find themselves at odds with “abundance” liberals and traditional antitrust centrists, who argue that dominant firm size, in and of itself, may not be as large a threat to democracy as alleged.

Yet this debate takes place atop some flawed empirical foundations. At the core is an assumption that lobbying expenditure data provides a reliable proxy for measuring concentration of political power. In a new working paper, I challenge that assumption, arguing instead that the apparent lack of correlation between rising economic concentration and lobbying market concentration obscures the rise of a more diffuse, opaque, and powerful influence ecosystem, enabled and financed by the wealth created through economic concentration. In short, what we see in lobbying data is not the absence of political capture, but its concealment.

Beyond Lobbying: A Complex Architecture of Political Influence

Quantitative analyses often treat political influence as a transactional marketplace where dollars spent on lobbying translate into policy influence. But this market analogy is conceptually flawed and empirically misleading. Lobbying, as captured by the Lobbying Disclosure Act, represents only a narrow slice of the influence economy. A growing share of influence is exercised through “dark money” groups, strategic litigation, media ownership, academic funding, “astroturf” campaigns, and campaign contributions by ultra-wealthy individuals.

These alternative channels of influence are not only substitutable with traditional lobbying; they are often more effective and less transparent. For instance, wealthy actors can achieve their policy goals by funding academic research that shifts public discourse, or by supporting litigation strategies that circumvent Congress altogether. These efforts rarely show up in lobbying disclosures, making them functionally invisible to traditional metrics.

The Empirical Illusion of Stable Lobbying Markets

Studies observing low or relatively stable concentration in lobbying expenditure patterns suggest that economic concentration does not lead to disproportionate political power. For example, a recent study by Nolan McCarty and Sepehr Shahshahani, comparing two decades of Lobbying Data Act expense reports to economic concentration and revenue, found that increasing corporate revenue does not lead to a disproportionate growth in the corporation’s lobbying spend and that an industry’s market concentration does not lead to a corresponding concentration in the industry’s lobbying “market,” suggesting there is little relationship between economic concentration and concentration of lobbying power. The reliability of this conclusion rests on the assumption that measurement error in lobbying data, though incomplete, is at least stable over time. If the magnitude of underreporting or misclassification is consistent year over year, then trends in lobbying concentration should still be informative about broader political economy dynamics, even if the data are imperfect.

This assumption has intuitive appeal. Longitudinal trends in a flawed dataset can, under some conditions, reveal meaningful shifts in behavior or structure. But this defense falters upon closer inspection, because it ignores the dynamic nature of political influence and the fungibility of influence-seeking behavior across channels. In practice, actors in political influence markets routinely engage in cross-channel substitution—dynamically shifting resources between lobbying, campaign finance, judicial advocacy, and public relations—in response to legal, political, and reputational shifts. These substitutions are not random; they are deliberate adaptations to maximize influence under changing constraints.

For example, following the 2007 Honest Leadership and Open Government Act (HLOGA), which imposed stricter disclosure requirements on lobbyists, many influence professionals rebranded themselves as “strategic consultants,” continuing their work without triggering Lobbying Disclosure Act reporting thresholds. Even more significantly, after Citizens United lifted restrictions on independent political spending, wealthy individuals moved significant resources into super PACs and dark money vehicles in ways that do not appear in lobbying disclosures. These shifts render the assumption of time-invariant measurement error implausible. As the legal and regulatory landscape changes, so too does the composition and visibility of political influence-seeking behavior.

Dynamic Substitution and the Post-Citizens United Shift

The 2010 Citizens United and related rulings drastically altered the strategic calculus of political influence. It enabled unlimited independent expenditures, allowing ultra-wealthy individuals to create expansive political infrastructures outside traditional corporate channels. These donors now routinely bypass firm rent-seeking allocations and operate instead through super PACs, nonprofit advocacy groups, and partisan media.

This shift from firm-based lobbying to capital-based influence is critical. A capital-holder with a diverse portfolio of shares across multiple industries may find it more efficient to invest in ideological advocacy and policy environments that favor their overall economic position rather than through individual firms’ budget allocations for political rent-seeking. This strategy is especially potent when coordinated across issue advocacy, electoral influence, and thought leadership.

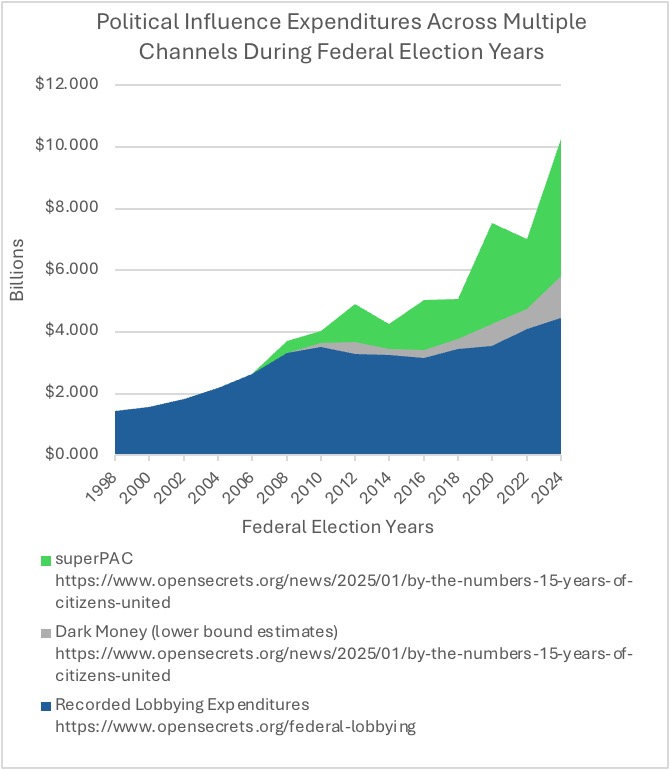

Notably, while aggregate corporate lobbying plateaued post-2010, independent expenditures by individuals and non-corporate entities skyrocketed. Consider the graph below constructed from data obtained from opensecrets.org. Using federal election years when campaign related influence expenditures are likely highest, I show that the previous exponential growth in lobbying prior to its sudden plateau may be accounted for by the explosion of alternative influence channels utilized by new forms of influence purchasing organizations made possible by Citizens United and its progeny. This divergence suggests a strategic reallocation of political investments, not a reduction in influence-seeking. It is not that political capture had stalled; it evolved beyond ostensibly observable lobbying to opaque new influence channels and beyond the firm as the principal influence market actor.

Note: All data from OpenSecrets.org

Market Concentration, Shareholder Wealth, and the Feedback Loop of Influence

The link between economic concentration and political capture is most visible in the distribution of extraordinary shareholder wealth. Dominant firms—particularly in sectors with significant barriers to entry like tech, finance, and pharmaceuticals—generate supra-competitive profits. These profits flow disproportionately to a small group of shareholders, often billionaires with significant stakes in multiple dominant firms. For example, just five companies account for over 50% of the Nasdaq index. Collectively, their market cap is worth over $16 trillion, and their profit margins range from 10% to over 50%.

Moreover, the top 1% of households now control over 50% of U.S. corporate equities, the top 10% own nearly 90%, and dominant large-cap firms drive the returns from that equity. This extreme skew ensures that shareholder value maximization, often invoked as the corporation’s principle purpose, effectively channels wealth to a small elite. To wit, Elon Musk just secured a $29 billion payment from Tesla, despite the electric vehicle company’s sliding sales, in part due to Musk’s politics that are antithetical to electric vehicle consumers. This elite, in turn, finances the ideological and institutional infrastructure that resists regulatory or redistributive reforms, reinforcing both economic and political concentration.

For example, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, and the Koch brothers derive the vast majority of their wealth from dominant firms in their respective sectors. Through a mixture of campaign contributions, media control, and think tank funding, these individuals have become central players in shaping the policy landscape, far beyond what traditional corporate lobbying would suggest. For example, the over $290 million spent by Elon Musk on influencing the 2024 election included direct campaign contributions as well as $240 million funneled into Musk’s own America PAC and $50 million toward political ads through Citizens for Sanity PAC. Musk has leveraged his acquisition of X (formerly Twitter) to support conservative and ultraright political forces worldwide, with the Associated Press finding that Musk’s engagement can result in political hopefuls gaining millions of views and tens of thousands of new followers on his platform. When Jeff Bezos acquired The Washington Post in 2013, he pledged journalistic independence. However, in early 2025 he directed that the Opinion section “write every day in support and defense of” free markets. In conjunction with Meta, Mark Zuckerberg has donated hundreds of millions of dollars to colleges and universities like MIT and UC Berkeley leading to concerns about how such largesse may influence research agendas. The billionaire Koch brothers fund a network of 91 think tanks and organizations including the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation that often promote “pro-business” viewpoints.

Reassessing Political Influence in a Multi-Channel Ecosystem

Researchers must move beyond single-channel metrics like lobbying data and adopt frameworks that capture the full architecture of political influence. This includes recognizing the strategic complementarities and dynamic substitution between campaign contributions, dark money issue advocacy, judicial influence, media ecosystems, and think tank networks. Influence is now wielded across a portfolio of channels, often in coordinated fashion and backed by extraordinary wealth.

Just as antitrust scholars recognize the importance of cumulative advantage and non-price effects in assessing market power, political economists must account for the structural and cumulative nature of influence. Political power is not merely purchased in discrete transactions; it is cultivated over time, embedded in relationships, and reinforced through systemic advantages in access, ideology, and information.

From Misdiagnosis to Reform

The forthcoming Supreme Court decision in NRSC v. FEC threatens to further erode transparency in an already opaque political economy. To understand and confront the risks this poses, we must discard the illusion that political power can be adequately assessed through lobbying data alone. Political capture in the post-Citizens United era is no longer primarily the domain of corporations, which were only ever a proxy for the profit interests of their owners—it is the domain of capital.

Abundance liberals risk sleepwalking into this moment. By focusing only on the consumer-welfare concerns of prices, output, and innovation, they miss the broader political implications of concentration. They treat economic and political power as separate, when in fact they are intertwined in a dangerous feedback loop.

Economic concentration produces wealth inequality; that wealth finances multi-channel influence; that influence protects the structures that maintain concentration. This isn’t a conspiracy; it’s a rational response to a regulatory environment that allows wealth to become political power. Addressing this risk does not mean we have to choose between bigness or democracy, a false dichotomy suggested by some of the debate between Neo-Brandeisians and supply-side abundance liberals.

Policy tools exist that can break the cycle of capture by the wealthy and minimize the democratic harms associated with concentration, while insuring that economies of scale actually deliver abundance. We need, among other things:

- Stronger antitrust enforcement to disperse economic power at its root.

- Wealth taxation that curtails the accumulation of influence capital.

- Campaign finance reform that restores public trust in electoral fairness.

- Media ownership rules that prevent consolidation of ideological gatekeeping.

- Enhanced transparency across all channels of political influence, not just lobbying.

- Academic disclosure standards that flag financial conflicts in policy research.

- Civil society watchdogs with the resources and access to investigate hidden influence.

- Legal reforms that broaden the definition of lobbying to include consulting and strategic advisory work.

The debate between Neo-Brandeisians, abundance liberals, and consumer welfare centrists is not merely theoretical. It reflects competing visions for the future of American democracy. If policymakers and scholars continue to underestimate the evolving architecture of political power and ignore the direct evidence of political capture by concentration-enabled capital, they risk providing rhetorical support for even further degradations to democratic responsiveness. The real threat of “bigness” isn’t just economic inefficiency. It’s the quiet capture of democracy itself.

Randy Kim is a municipal government attorney whose research and advocacy interests include economic justice, labor rights, the political dimensions of concentrated economic power, and their intersections. Opinions expressed herein are the author’s own and do not reflect the positions or opinions of his employers.

Railroad mergers haven’t happened in a while, and that’s a good thing. During the Reagan era, the country witnessed a rapid consolidation of its railroad industry. In the two decades following the 1980 Staggers Rail Act, the number of Class 1 freight railroads in the country fell from 39 to seven. The new millennium saw an industry dominated by four major railways that collectively controlled around 90 percent of the total domestic rail operating revenues.

In light of this rapid consolidation, regulators feared an eventual transcontinental rail duopoly. The Surface Transportation Board (STB) stymied railroad mergers in 2000, and issued new merger guidelines the following year, requiring that future deals would have to “enhance” competition. With the exception of Canadian Pacific-Kansas City Southern (CPKC), blessed with a waiver to be considered under the old merger guidelines, no Class 1 mergers have happened since the 2001 STB merger guidelines were released. That merger hiatus is set to be interrupted: In July, Union Pacific (UP) announced its intention to acquire Norfolk Southern (Norfolk) in an $85 billion deal.

The Economist touted the benefits of a UP-Norfolk tie-up, suggesting that the merger could lead to the “big four” railways becoming a “bigger two” railways. The magazine noted that UP-Norfolk merger would all but guarantee that BNSF and CSX combine as well. This potential rail duopoly presents a series of issues. Moving an already consolidated industry towards a duopoly means that shippers seeking to send traffic on overlapping routes will have fewer choices and will likely face higher prices. And railroad workers will have fewer employment options within an industry dominated by a duopoly. The STB will have to weigh the promised efficiencies against the harms to workers and shippers when considering this merger application.

Faster Speeds Are Not a Merger-Based Efficiency

Proponents of the UP-Norfolk merger argue that the arrangement will lead to faster trains, fewer delays, and better reliability. One purported benefit is that trains won’t need to interchange if they travel with the same railroad company along their entire route.

Here is The Economist’s merger-efficiency rationale, presumably helpfully shared by an industry lobbyist:

Avoiding interchanges between networks would mean faster trains and fewer delays. According to Oliver Wyman, a consultancy, the share of intermodal goods in America that travel by rail on journeys longer than 1,500 miles increases from 39% to 65% when served by a direct line.

There’s one problem with that rationale: It doesn’t depend on the merger. Instead, such benefits could be achieved in many cases via contract without the associated merger harms. (And that stat from Oliver Wyman, is not impressive: The causation might run the other way, in the sense that demand for transport on a route might cause a railroad to acquire or invest in a direct line).

The STB’s merger guidelines require prospective merging parties to answer the question of “whether the particular merger benefits upon which they are relying could be achieved by means short of merger.” If the claimed benefits from the UP-Norfolk tie-up could be achieved absent a merger, then it follows that those benefits should be given no weight in the STB’s adjudication.

An examination of the rail industry today shows that railroads can already streamline their connections between networks. Nothing prevents two railroads from contracting to facilitate deliveries between separate lines. Indeed, Jim Vena, chief executive of Union Pacific, has acknowledged that UP has a track-sharing arrangement with BNSF in the Northwest. Track-sharing arrangements like the UP-BNSF agreement allow a railroad to move freight across the rail lines owned by another railroad.

After the UP and Southern Pacific (SP) merger in 1995, UP gave trackage rights to over 3,800 miles of track to BNSF. A press release announcing the agreement stated that “BNSF will be able to serve every shipper that is served jointly by UP and SP today.” The agreement “guarantees strong rail competition for the Gulf Coast petrochemical belt, U.S.-Mexico border points, the Intermountain West, California, and along the Pacific Coast.” If UP can survive and thrive with the BNSF trackage-rights agreement, what’s stopping them from creating one with Norfolk?

A 2001 STB report analyzing the UP-SP merger stated that “BNSF has competed vigorously for the traffic opened up to it by the BNSF Agreement,” and that it had “become an effective competitive replacement for the competition that would otherwise have been lost or reduced when UP and SP merged.” The report also cites enhanced competition for shippers who previously had only one rail carrier option. A potential UP-Norfolk track-sharing agreement could allow UP to service customers in Ohio and Kentucky without needing a merger.

Track-sharing agreements can also reduce the number of interchanges necessary to deliver rail cars to customers. A railroad company with a track-sharing agreement can allow another company’s trains to move along its tracks to service customers across two different rail lines without needing to swap engines. If UP and Norfolk made such a trackage agreement, a shipper in Minnesota could already ship their product to Pennsylvania without needing to swap train engines on the way, obviating the need for a merger.

The merging parties might argue that expanding these agreements will place a strain on their train dispatching systems. When two companies make a track-sharing agreement, the “host” railroad generally handles train dispatching on its own line (see the “operations” section of this Southern Pacific trackage rights agreement as an example). The host railroad has incentive to put the tenant railroad’s train at the end of the line for dispatching. (Anyone who has ridden Amtrak knows the experience of waiting for a freight train to pass ahead of you.) Hence, track-sharing agreements might lead to sub-optimal scheduling that would be avoided if all of the trains were owned by the host railroad. Rather than making investments in their train-dispatching systems to address these issues, railroads would rather merge.

It may be the case that some coast-to-coast routes cannot be streamlined through contracts, and that there are merger-specific efficiencies. In any event, the modest gains in efficiency will have to be carefully weighed against the anticompetitive effects felt by shippers and workers.

Past Mergers Have Caused Service Disruptions

Another weakness with the purported merger efficiency is that such benefits are undermined by the experiences of prior merger. Past mergers could not guarantee service improvements in the medium term. These operational failures directly contradict the recent promises that further consolidation of the railroad industry will improve speed and efficiency.

The aforementioned railroad merger, CPKC, was completed in 2023. During May and June of 2025, the combined CPKC firm experienced widespread service disruptions after merging the two legacy IT systems. The CPKC rail network experienced elevated delays, slower average velocity, and decreased on-time performance. In a report to the STB describing the situation, CPKC explained “Unfortunately, despite intensive efforts by CPKC over more than two years to prepare for a smooth transition, the Day N IT systems cut-over encountered unexpected difficulties.”

These issues aren’t isolated to the CPKC merger. When the Class 1 railroad Conrail was split between Norfolk Southern and CSX in 1999, both Norfolk and CSX experienced service disruptions. Shippers also experienced service disruptions in 1997 from the UP and Southern Pacific merger. For these major mergers, degraded performance in the medium term seems to be the rule rather than the exception. The STB’s 2001 merger guidelines recognize this history and place less weight on merger efficiencies that could take years to be realized.

Shippers Could Face Higher Prices on Overlapping Routes

Most of the business press coverage on the merger has ignored or handwaved the overlapping routes between UP and Norfolk. The New York Times has this to say on the subject:

Because Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern do not operate in each other’s regions, the tie-up would not reduce choice between railroads in those areas. Still, the companies together accounted for 43 percent of all rail freight movements last year, according to an analysis of regulatory carload data by Jason Miller, a professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University. (emphasis added)

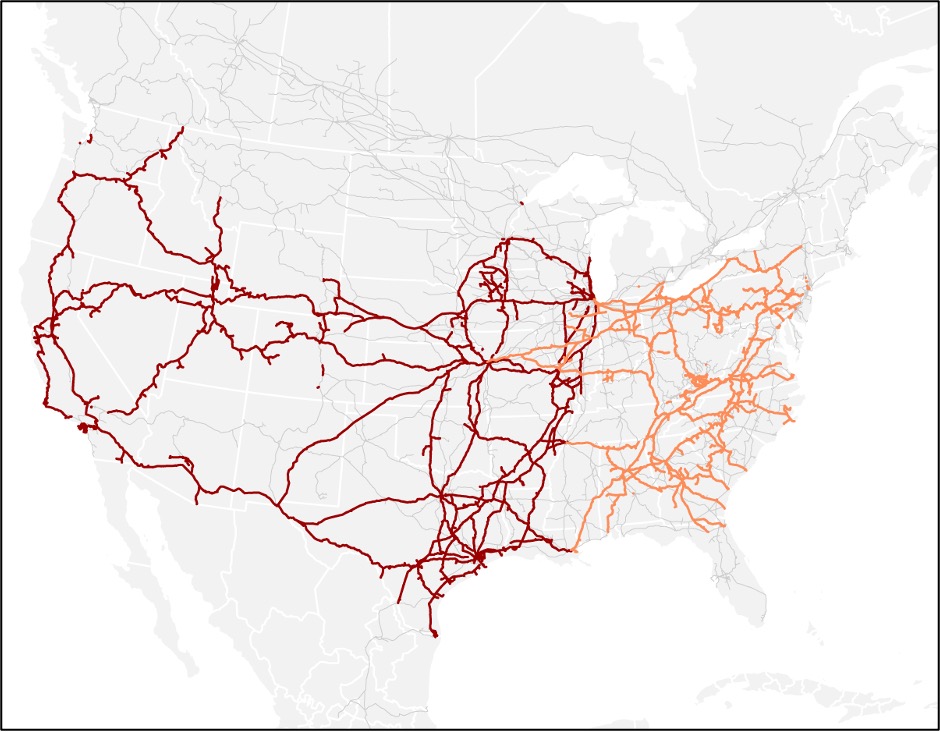

Yet the map in same New York Times story (inserted below) shows that overlapping UP-Norfolk routes exist throughout Missouri and Illinois. Shippers who need to send products from, say, Kansas City or St. Louis through Chicago will have one less option.

Note: Norfolk Southern lines are shown in orange. Union Pacific lines are shown in maroon.

The eventual rail duopoly that would result from this merger would give many shippers either one or two carriers to choose from. Some shippers may become “captive shippers” who are beholden to a single railroad (aka monopoly) for their shipping needs. These captive shippers would likely face higher prices and worse service quality.

Recently, regulators have attempted to use reciprocal switching to solve the issue of captive shippers. When a shipper only has access to a single Class 1 railroad, a reciprocal switching agreement allows another outside railroad to compete for that shipper’s contract. If the outside railroad wins the contract, the incumbent railroad facilitates the freight pickup in exchange for a fee. These agreements enhance competition for shipping contracts while also compensating the incumbent railroad for using their tracks. It’s a win for both parties.

Yet the STB has only mandated these reciprocal switching agreements when a Class 1 railroad failed to meet performance standards regarding consistency and reliability. The competition standard for captive shippers should not be whether they reach a minimum level of service quality. When considering the possibility of creating a rail duopoly in this country, the STB should contemplate expanding their use of reciprocal switching agreements to enhance competition. But this reform is not a panacea for shippers facing a railroad monopoly from a merger. A recent Seventh Circuit decision overturned the STB’s 2024 reciprocal switching rule, finding it “inconsistent with the Board’s statutory authority.” This decision shows that ensuring competition cannot be achieved solely through rulemaking.

Workers Are Right to Be Skeptical of This Deal

Per The Economist, unions might “lie on the tracks” when it comes to the UP-Norfolk merger. The resulting rail duopoly from this merger would reduce the number of prospective rail employers, and prevent the bidding up of rail worker wages by rival railroads. The likelihood of layoffs and lower wages has already caused the Transport Workers Union to oppose the merger. The Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers (SMART) union has also announced its opposition.

Despite the promises from UP’s and Norfolk’s management that they will preserve union jobs, the latest Class 1 merger should make rail workers skeptical. The recent CPKC post-merger service disruptions necessitated the temporary loaning of rail crews to address personnel shortages on their system. Yet one local SMART union alleges that the CPKC loaned crews reduced the number of yard jobs available for union employees. The local union alleges that CPKC took advantage of the service crisis to make these job changes. If that post-merger scenario is any guide, then the rail workers unions are justified in their opposition.

The Business Journalism Regarding the Deal Is Unbalanced

Despite the skepticism to the deal voiced by rail workers and shippers (the Freight Rail Customer Alliance representing over 3,500 businesses has criticized the proposed merger), business journalists seem enthusiastic about the deal. The New York Times and The Economist both trumpeted the deal, even citing the same industry analyst, Tony Hatch, in support of claimed efficiencies. Hatch’s support for the deal was widely shared throughout the business press, as he was also quoted by NPR, PBS, and the Bloomberg Podcast. Yet no message of skepticism of the merger efficiencies was widely shared in the media.

This is not to say that consulting a favorable industry expert is an issue. Yet instances like PBS gathering quotes from two analysts touting the benefits of the deal leaves readers with an unbalanced view. Our humble suggestion is that a business journalist, whether explaining a price hike or evaluating a merger, upon receiving a statement from an industry insider, should pick up the phone and seek an alternative opinion from a consumer or labor advocate (or, as a last resort, an economist not working for the merging parties).

The Surface Transportation Board Should Examine This Merger with a Skeptical Eye

The STB should ignore the glowing cheers from the business press and consider the harms to shippers and workers. This deal would likely create a transcontinental rail duopoly in this country, which would lead to even less choice for rail customers. The enhanced market power of the rail duopoly could lead to higher prices for consumers and less bargaining power for workers. Meanwhile, many of the promised service efficiencies could be gained without this merger. In light of the real costs and elusive benefits from this deal, the STB should examine the Union Pacific merger application with a skeptical eye and ensure that freight rail competition is maintained.

In a live discussion on Substack in June with Derek Thompson, neoliberal pundit Noah Smith called Dan Wang’s Breakneck a “companion volume” to Thompson’s and Klein’s recent bestseller Abundance. Wang is slated to speak at the upcoming Abundance 2025 conference, which is headlined by Klein and Thompson. Given the furious fight between the abundance faction and progressives for the soul of the Democratic party, I figured I should read it.

With Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future (W.W. Norton 2025), the Hoover Institution’s Dan Wang makes a powerful authorial debut, deftly tracing the promise and pitfalls of China’s “engineering state” model of governance, which Wang presents as a foil to the American “lawyerly” society. In many ways, Breakneck is an ethnography of a government. And the portions of the book that lean into that frame are generally the best (largely chapters 3, 5, and 6).

The book is fascinating and surprisingly fun—with Wang’s piercing dry wit interspersed at a near perfect frequency. It’s also frustrating. While the character of the engineering state is superbly developed, the points where its American “lawyerly” counterpart is brought into the mix are more tenuous. Wang leans heavily on a reiteration of Paul Sabin’s characterization of the American Left, from his book Public Citizens: The Attack on Big Government and the Remaking of American Liberalism (W.W. Norton 2021), with Wang’s explanation feeling paper thin next to the detailed portrait he paints of the engineering state.

Some of this is entirely understandable; Breakneck is, first and foremost, a book about China, not about the United States. The comparatively flimsy explanation of the lawyerly state, however, is largely taken from a footnote in earlier chapters to a central point of framing in the book’s conclusion.

While an overall terrific read, the book is somewhat uneven, great in most places but merely good in others. Perhaps the greatest criticism of the book is, in a way, a compliment to Wang as a writer: it should be at least 50 pages longer.

About Abundance?

Wang makes no secret that he is sympathetic to the abundance movement, though he seems to indicate that he may not count himself as a part of it. He writes on page 50:

Under banners like “abundance agenda,” “supply side progressivism,” and “progress studies,” various movements are trying to loosen American supply constraints. These are excellent ideas that I hope are broadly adopted.

All of those movements are really better understood as constituents of the broader abundance movement. After all, people within the movement will identify them as such, plus they share a common network of funders, conferences, and prominent personalities.

Wang, though is not wedded to the abundance “lens,” as Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson term it, and instead is extremely clear in calling attention to some of the downsides such an approach entails when not balanced against other concerns.

In Wang’s parlance, the abundance movement seeks to make the United States less lawyerly and more engineering. And while Breakneck is supportive of that aim, it also cautions against overdoing it and promotes seeking to strike an appropriate balance between lawyers and engineers.

This is one reason why even many critics of abundance may enjoy the book. One of the more frequent criticisms, both of Abundance and the movement sharing its name, is that it fails to engage in the hard tradeoffs that can accompany the quest for efficiency. Proponents will laud China’s infrastructure without considering the limitations on political freedoms or repression of ethnic minorities that enable its monumental building. Or, as Klein and Thompson do, they will lament the old times when Americans built things like the transcontinental railroad, with no acknowledgement of the genocide, racialized exploitation, or corruption that enabled it.

Wang, largely, avoids this pitfall by confronting those questions head-on. He acknowledges, repeatedly, the environmental damage, persecution of ethnic minorities, and disastrous social engineering projects that came with high-speed rail, monumental bridges, and dams. The question presented by this acknowledgment, which could have been answered more substantially, though, is how possible it is to have an engineering society that steers around the worst of these harms.

First Kill All the Lawyers?

The single biggest flaw in Breakneck is its chronicling of the role and influence of lawyers in the United States. The topline argument here is simple enough: we used to be more of a nation of engineers before becoming extremely lawyerly in the back half of the twentieth century.

In particular, Wang points to Paul Sabin’s Public Citizens and blames this development substantially on the New Left, spearheaded by figures like Ralph Nader who continually sued the government to enact progressive ends. Yet Breakneck barely addresses the necessity of the lawyerly society to preserve and defend the public from powerful interests or corrupt political regimes. Red tape has its downsides, but it also can be an impediment to the worst impulses of those in power. Particularly in the age of Trumpian power-tripping and influence peddling, with the Supreme Court playing dead (at times quite convincingly), many people would probably like it if lawyers were able to slow things down more at this particular point.

At one point Wang proxies the level of lawyerliness on the number of lawyers per capita the United States has (p.14). Even by that metric, Israel, the Dominican Republic, Italy and Brazil are more lawyerly. Do they all struggle to build more than the United States?

There is also an issue of how one counts the lawyers. In the European continental civil law system, many nations separate out “lawyers” from “magistrates.” In the United States, by contrast, everyone who practices law is a lawyer, whether they are a defense attorney, a prosecutor, or a judge. In some places like France, for instance, prosecutors and judges are excluded. So when Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson make a similar point to Wang and cite the United States as having four times the lawyers per capita as France (Abundance p.92-93), it is, at best, misleading.