After years of inflation-driven concerns over the state of the economy, it seems that the mythical soft landing has been achieved; things aren’t perfect but inflation is down without the United States hitting a recession. The labor market has weakened some in recent months, but is still largely okay and the Federal Reserve has started cutting rates in a move to ease downward pressure on employment. In 2022, Bloomberg Economics put the odds of a recession within the next year at 100 percent. Two years later and not only has there not been a recession, but inflation is down, interest rates are going down, and recent GDP growth has been higher than it was for the previous decade.

Over the last several months, while this situation was crystalizing, many have credited Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell with achieving the once-mythical soft landing. That’s a mistake. There are multiple reasons why the Fed has been ineffective at best at wielding monetary policy in its recent inflation fighting. Such an explanation doesn’t fit the available empirics—or its advocates’ own model of how interest rates work.

The issue is especially salient because many of Powell’s defenders, including neoliberal economists and pundits, cling to the view that inflation was driven by demand-side factors. This spending-is-to-blame philosophy conveniently exonerates businesses for having any role in driving inflation. If demand-side explanations can be excluded, then attention would shift back to supply-based theories of inflation, including price gouging and coordinated price increases. And that would lead to very different policy implications.

A Brief History Lesson

Let’s rewind to when the fight over monetary policy was heating up in 2022. A variety of different economic shocks have hit the United States: the worst pandemic in a century, major emergency stimulus, brittle supply chains, and a land war in Europe (between Russia—one of the world’s major oil producers—and Ukraine—one of its major grain producers) have all rocked markets in just two years. Then, corporations in concentrated markets seize on the pricing mayhem to pad profits, extending inflationary pressures. At this point, such rent-seeking is well documented. That includes work from researchers from at least three regional Federal Reserve Banks (Boston, San Francisco, and Kansas City), the Bank of Canada, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank.

Because of this suite of shocks, inflation spiked more aggressively than it had for decades. That spike prompted the Fed to begin a major series of interest rate hikes to attempt to rein in price increases. This whole time there’s a back and forth among economists and pundits on what caused inflation, how long it would last, and what to do about it.

On one side you had Team Transitory, who said that the cause was a bunch of exogenous shocks, inflation wouldn’t last all that long, and we should wait things out because inflation will naturally subside and using monetary policy risked hurting workers.

On the other was what I called Team Crash The Economy, who said that the cause of inflation was fiscal stimulus leading to excess spending, price growth wouldn’t return to normal on its own, and the Fed should aggressively hike interest rates to cool the economy—including destroying millions of jobs. Larry Summers infamously called for ten percent unemployment while lounging on a beach.

In retrospect, Team Transitory was largely correct about the causes; fiscal stimulus played a role, but wasn’t responsible for most of inflation. Technically, Team Crash The Economy was right on the timeframe question, but the reasoning behind why inflation lasted a long time was demonstrably incorrect. Conversely, Team Transitory was technically wrong about the timeframe, but the reasoning was at least partially true.

But then there’s the big question of what the solution was. Both teams have taken victory laps: Team Transitory back in 2023 when inflation eased, except for a few lagging variables (housing, wages) and commodities (oil) that kept overall measures high; and Team Crash The Economy over the summer, when they pointed at decreased inflation and credited Jerome Powell and the Fed for the result.

The Econ 101 Model

The intro macro model for the relationship between inflation and interest rates is largely just an inverse relationship. As interest rates are eased, businesses face cheaper borrowing costs, inducing them to scale up operations, creating new jobs. Then when the labor market tightens, it creates a “wage-price spiral.” As people get paid more, they spend more, leading suppliers to scale up again, further tightening the labor market, leading to higher wages, and on and on. In this econ 101 telling, the key link between inflation and interest rates is those pesky workers demanding higher wages, which create a cycle of increasing demand. That’s why the solution is a form of “demand destruction,” forcing consumers to consume less (by making credit more expensive) in order to reduce demand-side pressure on prices.

So if a central bank finds itself making monetary policy using this framework in an inflationary environment, what does it do? It hikes rates, making borrowing costs prohibitively high, which leads firms to stop expanding and, if the costs increase enough, to actually shrink their business via measures like layoffs, putting an end to wage increases, or even shuttering entirely. And then as wages stagnate (or, in extreme cases, decrease), there’s less demand, so prices don’t continue their rapid increase (or, in extreme cases, fall).

Within the econ 101 frame, this makes sense and is the obvious choice. But in the real world, it didn’t fight inflation. Nearly every step of that theoretical model can be observed and empirics clearly do not show the proscribed pattern. On top of that, there are blatant theoretical holes in that narrative.

Let’s start with unemployment as the key channel to impact inflation. If the textbook econ 101 model is correct, we should be able to see it in a few different datasets. The unemployment rate (Figure 1) should go up as the Fed began raising rates in March 2022, and should correspond to a rise in initial filings for unemployment insurance (Figure 2) and a fall in job vacancies (Figure 3) and new job creation (Figure 3(a)).

Figure 1: Unemployment rate (blue, left) and effective federal funds rate (red, left) vs. date.

Figure 2: Initial unemployment insurance claims (blue, left) and effective fed funds rate (red, right) vs. date

Only one of those trends is borne out by the data. Job openings have declined, and the monthly change (Figure 3(a)) has been lower recently. It’s worth noting, however, that the number of job openings is still historically high, above anything pre-pandemic. Plus demand destruction requires a decrease in real spending power, which a change in job openings alone won’t do.

Figure 3: Total job openings (blue, left) and effective federal funds rate (red, right) vs. date.

Figure 3(a): Monthly change in job openings (blue, left) and effective fed funds rate (red, right) vs. date.

No dice. But maybe what happened is that work prospects got bad and that led a lot of people to exit the labor force entirely. Except that didn’t happen either. The labor force participation rate (Figure 4) has remained below 2019 levels, but reached its post-pandemic relative maximum of 62.8 percent in August 2023, the month at the end of the Fed’s rate hikes, and remained steady since.

Figure 4: Labor force participation rate (blue, left) and effective fed funds rate (red, right) vs. date.

Now let’s expand the intro model a little bit to see if there are factors that could be a viable channel to get from rate hikes to a fall in inflation. When the Fed increases rates, there are a bunch of things that should be expected to happen as a result of higher borrowing costs:

- Private investment (Figure 5) should fall, reflecting firms being unable to afford expanding with less access to credit.

- Consumer expenditures (Figure 6) should fall, reflecting their lines of credit (including personal loans, mortgages, car loans, and credit cards) costing more to use and wage growth slowing.

- Personal savings (Figure 7) should decrease as people eat into savings as a substitute for consumer credit. The savings rate (Figure 8) should fall, as more personal income is diverted directly to consumption to cover for using less credit.

Any of these could potentially be a mechanism for monetary policy to lower aggregate demand.

Figure 5: Real gross private investment (blue, left) and effective fed funds (red, right) vs. date.

Figure 6: Real consumption expenditures (blue, left) and effective fed funds rate (red, right) vs. date.

Figure 7: Personal Savings in nominal billions of dollars (blue, left) and effective fed funds rate (red, right) vs. date

Figure 8: Personal savings rate (blue, left) and effective fed funds rate (red, right) vs. date.

Yet exactly none of those causes are reflected in the data. (Total personal savings looks at first glance like it dipped, but it actually increased and stabilized during the course of the rate hikes.) If demand destruction does occur, it would presumably be through some combination of those factors. If there’s no loss of jobs, no drop in investment or consumption, and no change in personal savings rates, how exactly does increasing interest rates lead to lower inflation?

The short answer, at least in this case, is that it probably didn’t. This entire model of monetary policy presupposes demand-side causes of price increases, which were only a minority of the post-Covid inflation.

Inflation Doesn’t Capture the Full Cost of Living

That isn’t to say that the Fed’s rate hikes did nothing to impact workers and consumers. They actually made things worse. One long standing debate from the past couple of years is why public sentiment has remained negative on the economy even as most indicators have been broadly positive. A big part of that sentiment gap can be explained by differences in how lay people and economists use the same word. In an everyday sense, “inflation” means a rise in cost of living. But in economics, “inflation” is a change in the price level of a fixed basket of goods compared across time. That creates tension in how we discuss inflation; it’s atechnical measure that is often used in a general sense.

That meaning gap wouldn’t be a huge issue if the technical measure was a consistently good proxy for how people experience changes in the cost of living. There are prices that are important to the cost of living, however, that are excluded from the basket used to measure inflation. Chief among them is the cost of borrowing.

From a mechanical point of view, excluding interest rates on consumer credit is very reasonable; if they were to be left in, then it would muddle the relationship between interest rates and inflation since inflation would be defined as a function of interest rates. While it makes sense for technical economic analysis, this exclusion makes measures of inflation a poor approximation of the actual situation people experience.

Consumers experience higher interest rates on their access to credit as a sort of inflation. After all, it makes their lives more expensive. As a result, people’s lives can get more costly even in the face of easing inflation. (Not to mention that lower inflation still doesn’t represent a drop in prices.)

Put everything together and you get a story that goes something like this: multiple shocks, mostly, though not entirely, stemming from disruptions to supply usher in a major episode of inflation. As supply constraints eased, inflation fell. Although not before many unscrupulous firms took advantage of the situation by raising prices by more than their costs increased.

Meanwhile, neoliberal economists like Jason Furman and Larry Summers publicly pressured the Fed into hiking rates in an attempt to elevate unemployment and usher in demand destruction. Jerome Powell and the Fed ultimately did so, which made consumer credit more expensive, in turn that kept consumer confidence low because even though inflation was easing, it didn’t feel like it. Through those higher borrowing costs, the Fed has been responsible for eroding consumer confidence, threatening democracy, and slowing the green energy transition.

Yet what the data indicate is that these trends happened in parallel; over similar timeframes but not with a causal relationship between them. The expected changes to unemployment, investment, consumption, and personal saving are all missing. Absent those channels, there isn’t a link that gets from higher interest rates to lower inflation. It’s entirely possible that there is a causal channel somewhere, but until it’s identified and explicated, there is no reason to defer to the econ 101 model.

Particularly given the stink that neoclassical economists made about evidence for sellers’ inflation, they should be held to a similar standard for their crediting of the Fed for lower inflation and implicitly putting the blame on consumers and workers. The data just don’t fit their model.

It’s always better to be a monopolist. “Ruinous competition” is a drag on a company’s profits, particularly when slothful incumbents are forced to compete on the merits. In the case of banks, competition on the merits means increasing rates on deposits for customers with sizeable savings or decreasing overdraft fees for customers with limited funds.

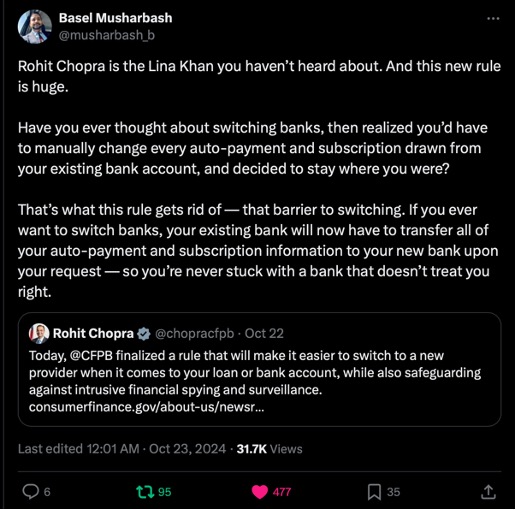

Last week, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) finalized a rule that requires financial institutions, credit card issuers, and other financial providers to unlock a customer’s personal financial data—including her transaction history—and transfer it to another provider at the consumer’s request for free. It marks the CFPB’s attempt to activate dormant legal authority of Section 1033 of the Consumer Financial Protection Act. Officially dubbed the “Personal Financial Data Rights” rule, or more casually the “Open Banking” rule, the measure was greeted by those in the budding anti-monopolist movement with glee.

Indeed, FTC Chair Lina Khan, the ultimate champion of competition, tweeted an endorsement of the CFPB’s new rule.

But it wasn’t all rave reviews. The Open Banking rule was also greeted by a swift lawsuit from the Bank Policy Institute (BPI), alleging that the bureau exceeded its statutory authority. The lawsuit also claims the rule risks the “safety and soundness” of the banking system by limiting banks’ discretion to deny upstart banks access to transaction histories. Based on its website, BPI’s membership includes JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Barclays, or what I will call the “incumbent banks.” And JP Morgan’s Jaime Dimon is the Chairman of BPI. Why are the incumbent banks so angry about being compelled to share these transaction histories with upstarts, when such data are arguably the property of the banks’ clients in the first place?

When I first heard about the CFPB’s new rule, I didn’t understand why I needed a regulatory intervention to play one bank off another. For example, after being offered a high CD rate by a scrappy bank, I asked my stodgy bank to match it, only to be ignored by my stodgy bank; I proceeded to write a check from the stodgy bank to the scrappier rival. But having studied the issue, I now understand the particular market failure that the rule seeks to address.

The Rule Would Induce More Aggressive Offers by Upstart Banks

When an upstart bank seeks to pick off a customer from an incumbent bank, the upstart would prefer to extend the most aggressive offer possible, as an inducement to overcome any switching costs that customer might incur. (Fun fact: When interest rates were regulated and interest on checking accounts was banned, banks used to compete by offering toasters to customers at rival banks!) Today’s competitive offer by a rival bank might include a host of ancillary services or “cross-sales” alongside a checking account, such as a credit card, a loan, a line of credit, and payment services. The terms of such offers are governed by the customer’s creditworthiness.

And that’s the catch—the incumbent bank and only the incumbent bank has access to the customer’s transaction history, which includes nuggets like your history of maintaining a balance, overdraft tendencies, and relative timing of payments to income streams. The scrappy upstart, by contrast, is flying blind. And this granular information cannot be obtained through the purchase of a credit report.

Economists refer to such a predicament as “asymmetric information,” and in 2001 three economists even won a Nobel prize for explaining how such asymmetries lead to market failures. In the absence of this information, when formulating its offer, the upstart bank must assume the average tendencies of the borrower based on some peer group, or even worse, it might hedge by assuming the borrower’s creditworthiness is slightly worse than average. As a result, the competitive offer is unnecessary weaker than it could be, and too many customers are sticking with their stodgy (and stingy) bank.

(A fun digression: Some employers inject provisions into a worker’s employment contract that create similar frictions to substitution, which relaxes competitive pressure on wages. You’ve likely heard of a non-compete, which is the ultimate friction. But you may not have heard of a “right-to-match” provision, which gives the incumbent employer a right to match any outside offer from a rival employer. Because the rival employer knows of the provision, and because it’s costly for the rival to formulate an offer, most rivals will give up and the employee never enjoys the benefit of competition.)

The purpose of the Open Banking rule is to induce more aggressive offers by upstart banks and thereby overcome the switching costs associated with changing one’s bank. Put differently, it juices the part of the fin-tech community that seeks to assist consumers, which likely explains the narrow opposition to the rule from incumbent players only. Suppose the customer’s switching costs are $100 and the (weakened) offer from an upstart would improve the customer by $90; under those circumstances, the customer stays put. But if the rule can induce more aggressive offers, boosting the customer benefits of switching to (say) $200, the customer moves. Or she now, with a powerful offer in hand, credibly threatens to switch banks and her stodgy bank improves her terms.

The Open Banking Rule Could Generate Billions in Annual Benefits

The economists of the CFPB have tried to value what this enhanced competition might mean for bank customers. At page 525 of the rule, in a section titled “Potential Benefits and Costs to Consumers and Covered Persons,” the economists explain their valuation methodology:

First, those consumers who switch may earn higher interest rates or pay lower fees. To estimate the potential size of this benefit, the CFPB assumes for this analysis that of the approximately $19 trillion 207 in domestic deposits at FDIC- and NCUA-insured institutions, a little under a third ($6 trillion) are interest-bearing deposits held by consumers, as opposed to accounts held by businesses or noninterest-bearing accounts. If, due to the rule, even one percent of consumer deposits were shifted from lower earning deposit accounts to those with interest rates one percentage point (100 basis points) higher, consumers would earn an additional $600 million annually in interest. Similarly, if due to the rule, consumers were able to switch accounts and thereby avoid even one percent of the overdraft and NSF fees they currently pay, they would pay at least $77 million less in fees per year.

Hence, bank customers who switch banks due to more robust competitive offers made possible by the Open Banking rule would benefit by $677 million per year, based on very conservative assumptions about substitution. And this estimate does not include benefits created for those customers who stay put but nevertheless benefit from the mere threat of leaving. The economists explain that competitive reactions by incumbent banks could lead to a doubling of the aforementioned benefits, to the extent that interest rates on deposits of the non-switchers increase by a mere one basis point. Those benefits would be a transfer from incumbent banks to consumers.

Beware of Fraud Arguments

The Open Banking rule requires that a bank make “covered data” available in electronic form to consumers and to certain “authorized third parties” aka the upstart banks. Covered data includes information about transactions, costs, charges, and usage. The rule spells out what an authorized third party must do to get the covered data, as well as what the “data provider” (aka the incumbent bank) must do upon receiving such a request. The data provider will run its normal fraud review process upon receipt of a data request. Indeed, CFPB even included a provision that states when the data provider has a “legitimate risk management concern,” that concern may trump the data sharing rule.

So any claim that the BPI lawsuit is motivated to protect consumers against fraud or to ensure the safety and soundness of the banking system seems farfetched. The more likely motivation for the challenge is that the Open Banking rule will spur competition among banks, and hence put downward pressure on the incumbent banks’ hefty margins. To wit, JP Morgan Chase, America’s biggest bank, has thrived in a rising rate environment, posting record net income figures since 2022. As the CFPB economists estimate, the rule could raise rates on deposits and reduce rates on overdraft fees, cutting into these record margins. In a similar vein, the CFPB’s new rule might spark competition in the nascent payment system market. Some large banks would like to build their own payment systems (think BoA’s Zelle). By compelling the incumbent banks to share their customers’ transaction histories, however, the Open Banking rule reduces the costs for a scrappy entrant to build a competing payment system. If pay-by-bank gets going, it will be a threat to the incumbent banks’ lucrative credit card and debit card interchange fees. And that threat alone provides billions of reasons to sue the CFPB.

As Google faces aggressive scrutiny from the Department of Justice—with the search trial moving to the remedies phase and the ad tech trial moving to closing arguments—there’s an elephant in the room that many antitrust watchers are failing to see: YouTube.

With the platform’s presence on our phones, the part it plays in our online searches, its rapid invasion of our living rooms, and the volume of advertising it serves us, YouTube is an increasingly unavoidable part of our lives. We and other observers have called it “the third leg of the stool that supports Google’s monopoly.” Separating the video giant from the rest of the Google behemoth makes sense as one of the remedies for Google’s decades of monopoly behavior and would reshape the digital landscape for the better—ultimately benefiting consumers, shareholders, and smaller companies in a market newly opened to competition.

Judge Amit Mehta is currently considering what remedies to impose after ruling against Google in August in its landmark search engine antitrust trial. Requiring divestment of one or more business units, like YouTube, is one of his options. A second big antitrust trial, with the government alleging Google illegally controls the advertising technology market, is already underway; and here, too, if the government prevails, divestment would be an option. In the interest of market competition and consumer choice, YouTube—which is intimately bound up with Google’s domination of both sectors—should be among the Google units to be spun off.

Google dominates search with more than 80% of the market, giving it an effective monopoly on the flow of internet information. But YouTube by itself has been recognized as “the world’s second-largest search engine,” handling an estimated 3 billion searches per month. As one commentator noted, after YouTube was founded in 2005, it was “purchased just over a year later by none other than Google, giving it control over the top two search engines on this list.” Another commentator noted recently in the New York Times that, “The gargantuan video site is a lot of things to a lot of people—in different ways, YouTube is a little bit like TikTok, a little like Twitch and a little like Netflix—but I think we underappreciate how often YouTube is a better Google. That is, often YouTube is the best place online to find reliable and substantive knowledge and information on a huge variety of subjects.”

Especially for many younger people, who increasingly prefer video content, YouTube is already the search engine of choice. For these reasons, the European Union recently classified YouTube not only as a large online platform, but a large online search engine. And because YouTube is so tightly integrated with Google Search, it doesn’t represent true competition.

Right now, Google faces little pressure to innovate because it dominates nearly every business it’s in; and when it does innovate, it does so with an eye toward further cementing its complete control of the internet. Google’s recent “innovations” have significantly degraded the Google Search experience, as the company increasingly curtails linking to external sites and instead imposes a “walled garden” strategy that keeps you interacting only with Google’s own content instead of the content you really want. The collateral damage is vast, not only to consumers, but also to content publishers, news organizations, and a variety of other third-party businesses that depend on Google traffic for revenue.

Separating YouTube from the rest of Google would shake up the search, ads, and video markets, and—freed from the market imperatives of a giant corporate parent—could take YouTube development in new directions, with the scale, resources, and user base to challenge Google to compete on features and quality. This would yield more diverse content that better meets user needs, and new opportunities for smaller players to enter the market and innovate.

By owning supply (ad inventory) and setting the terms of demand, Google has been able to charge inflated prices for online advertising while funneling disproportionate revenue to itself and YouTube. Internal communications confirm Google knows their ad fees are roughly double the fair market rate, which one employee admitted is “not long term defensible.” But when you own the entire market, you can charge whatever you want, and Google’s vertical integration has killed competition and put the squeeze on advertisers and publishers. Numerous companies have blamed Google for putting them out of business; new startups that try to break into the business find it tough going.

An independent YouTube would enable the new video company to go head-to-head with Google and negotiate its own deals with advertisers. This would likely lower the fees that Google charged advertisers, increase transparency in how digital ads are bought and sold, create more opportunities for advertisers to effectively reach more target audiences through more platforms, and also open up space for smaller ad tech companies to thrive.

All of this would unlock significant new shareholder value. An independent YouTube’s unique market position and strong brand identity would make it a highly attractive investment, pushing its valuation higher than it is today; analysts have speculated that it could be worth up to $400 billion on its own. Its video-based business model is sufficiently different from Google’s core business of search, so it could attract a different class of investors with different expectations, allowing it to grow more independently and with greater strategic flexibility. And a smaller and more nimble Google would likely provide better returns to its own shareholders.

In short, it’s time to face the elephant in the room, and require Google to spin off YouTube into an independent entity positioned to be a market counterweight. This would be a win-win-win-win: for advertisers, publishers, competitors, and consumers. And it would kick one leg out from under the stool that props up Google’s internet monopoly, which has done too much market damage in too many ways for way too long.

Emily Peterson-Cassin is the Director of Corporate Power at Demand Progress, a national grassroots group with over nearly one million affiliated activists who fight for basic rights and freedoms needed for a modern democracy.

Each semester at universities around the world, students in introductory economic classes are generally told the same stories. Perhaps to the surprise of some students who have met human beings, economists teach their classes that human beings are rational creatures who primarily seek to maximize their own utility in making choices. These students are also taught that firms are led by perfectly rational people who can objectively measure worker productivity and respond quickly to new information. In addition, economists teach that the competitive nature of markets forces rational business leaders to provide goods and services that benefit society. And finally—and for some economists this seems to be the most important point—all of these beneficial products are bought and sold by rational consumers and producers without any need for government direction.

Perhaps some students don’t believe these tales. But it must appear to most students that economists have always believed the stories they tell about rational human beings and competitive markets.

Once upon a time, however people writing about economics were less confident about the behavior of people in business. Consider this quote from the 18th century: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

Yes, that is Adam Smith. When Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations is invoked today, it is often used to convey the magical invisible hand of the market. Smith certainly mentioned the invisible hand. But in reality, Smith only mentioned this concept one time in the entire Wealth of Nations. So, we really can’t believe this was Smith’s central point. As Paul Sagar explains, Smith was primarily concerned with the danger of monopoly power.

About a century later, the economist Thorstein Veblen shared the same concern. Introductory students today are not likely to hear much about Veblen. But once upon a time, it was a different story in economics. In fact, Kenneth Arrow, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1972, argued that “Thorsten Veblen’s ideas pervaded the intellectual culture” at Columbia University when Arrow was a graduate student in economics before World War II.

Veblen’s writings mostly appeared during the Robber Baron era around the beginning of the 20th century. Decades before Veblen, it appears Americans seemed to think that markets did not need much government intervention. This approach to markets, though, didn’t quite work. By the end of the 19th century—just as we can imagine Adam Smith would have predicted a century before—the American economy was dominated by monopoly power. Confronted with the late 19th century economy dominated by the Robber Barons, Veblen found it hard to believe that competitive markets were the norm and what business leaders did always made society better off.

Veblen was also highly skeptical of the idea that human beings were rational utility maximizers. As Veblen sarcastically wrote in 1898:

The hedonistic conception of man is that of a lightning calculator of pleasures and pains who oscillates like a homogeneous globule of desire of happiness under the impulse of stimuli that shift him about the area, but leave him intact.

Veblen was not the only who questioned the idea that human beings were rational “lightning calculators.”John Maynard Keynes, who argued markets were often motivated by “animal spirits,” also noted:

It is not a correct deduction from the Principles of Economics that enlightened self-interest always operates in the public interest. Nor is it true that self-interest generally is enlightened; more often individuals acting separately to promote their own ends are too ignorant or too weak to attain even these.

For a person living before World War II, what Veblen and Keynes argued probably wasn’t very surprising. Many people living at this time probably doubted the existence of competitive markets populated by rational business leaders consistently producing socially beneficial results. The Robber Baron era very much contradicted that story. And the behavior of the Robber Barons led to the enactment of antitrust laws, the federal income tax, government regulations of business, and much of the New Deal. All of this makes clear that many people in the first half of the 20th century certainly didn’t believe that the market, when left to its own devices, always produced outcomes that enriched the lives of everyone in society.

Of course, all of this government intervention didn’t make the wealthy Robber Barons happy. But what could the wealthy do? In the early 20th century, there weren’t many people who believed that unfettered markets were always a great idea.

This all changed after World War II. Led by Milton Friedman and his allies at the Chicago School, the wisdom of Smith, Veblen, and Keynes was gradually pushed aside. Suddenly economists were arguing human beings were rational, markets tend to be competitive, and government intrusion in the marketplace was a bad idea. The question is how did this happen?

One could argue that maybe government policy was too successful. Higher taxes and more government regulation mitigated the power of the very wealthy. Incomes in the middle of the 20th century became more equal. And as time went by, maybe people just forgot how the Robber Barons behaved.

Or maybe the Robber Barons just used their money to purchase some economists as apologists. Economists teach that people respond to incentives. Maybe that is true for economists as well!

Both of these are great stories. And these stories might very well be true. But neither story is very funny!

For a better story, let’s talk about a show that probably most people don’t know existed.

Back in 2015, Rob Lowe and Fred Savage starred in a sit-com called “The Grinder.”The show only lasted a season. So perhaps not everyone found this as funny as me. Nevertheless, I think the second episode of this show’s only season very much captures what Milton Friedman and his allies did to our understanding of economics.

Let’s start with the show’s premise. Rob Lowe plays a television actor, named Dean Sanderson, who starred as the lead in an over-the-top law drama called “The Grinder.” As the show begins, Lowe becomes dissatisfied with his show and moves to Boise, Idaho. There he moves in with his brother, Stewart, who is married with children. Played by Fred Savage, Stewart is an actual lawyer. At the onset of the show, Dean makes it clear that he thinks his experience as an overly dramatic actor on a legal drama could help his brother argue real cases. (You can watch parts of the trailer here.)

Of course, Lowe is just an actor. And again, an overly dramatic actor. Although Dean knows some legal phrases, he has no idea what they mean. Yet that doesn’t stop him from offering overly dramatic arguments that don’t always make sense.

In the second episode, Dean offers one of the best examples of a nonsensical argument. In the first minutes of the episode, Stewart is discussing which legal case his firm should choose next. Here is how Dean argues the firm should select its next case:

Dean: We don’t choose the case. We let the case… choose us.

Stewart: That’s insane. If we throw out all these cases, we will go out of business. This is a real law firm. We can’t do that.

Dean: But what… if we could!

Stewart: But we can’t.

Dean: But what… if we could!

Yes, Dean generally paused dramatically as he said this. And this is what made it funny (and as you can see here and here and here… people who heard Rob Lowe say this thought this was hilarious!).

Something like this phrase gets repeated several times in the episode. The case Dean chooses turns out to be one where the law firm’s clients don’t have a legal argument to stand on. When Dean is told that the fate of his brother’s clients was perfectly consistent with the law, he responds:

But what… if it wasn’t!

As Stewart notes in the episode: “It’s impossible to argue [with such statements]. You can use it any situation. Because… it means nothing.”

Okay, what does all this have to do with the turn economics took in the 20th century?

I would like us all imagining that once upon a time, Milton Friedman and his colleagues at the Chicago School were told:

Adam Smith knew markets were not always competitive and people in business didn’t always take actions that made society better off. Veblen and Keynes also both knew that people were not perfectly rational, and they both knew markets didn’t always work. We have known all of this for decades. You simply can’t assume markets are competitive and human beings are rational!

Upon hearing this, Friedman and his colleagues effectively said (just like Dean):

But what… if we could!

There were a few economists, like Herbert Simon, who tried to argue at the time human beings weren’t perfectly rational. But each time the Chicago School heard this argument, they simply said:

But what… if they were!

Just like Stewart noted, there is no real response to this line of reasoning. Those who use this technique aren’t providing a real argument. What Milton Friedman and the Chicago School assumed about markets and rationality wasn’t technically true. All they were doing was taking these assumptions to their natural conclusion.

Unfortunately, those assumptions often dictated the conclusions reached. And this intellectual exercise eventually resulted in future generations of students being taught it was okay to start with the assumption of competitive markets and rational actors. And it was okay to build arguments, based on those assumptions, that led economists to argue taxes on the rich should be lower, antitrust laws should be weakened, and government regulations should be dismantled. In fact, given the money rich people would pay to hear such stories, it was in the interest of economists to make such arguments.

Yes, maybe this story is all about people just forgetting what happened and economists responding to their monetary incentives.

Maybe, though, this is just a school of thought in economics doing their best Dean Sanderson impression. Just maybe, once upon a time Milton Friedman and the Chicago School really were told you can’t just assume markets are competitive and human beings are rational. And just maybe, they all just collective said:

But what… if we could!

In February 2023, Doha Mekki, the Principal Deputy AAG for Antitrust announced the withdrawal of the FTC-DOJ guidelines on information exchange. It had become painfully apparent that oligopolists had found exchanges of confidential business information to be an effective means of restraining competition without entering into overt conspiracies. In December of that year, we published our article, Pooling and Exchanging Competitively Sensitive Information Among Rivals: Absolutely Illegal Not Just Unreasonable, 92 U. Cin. L. Rev. 334 (2023), on the exchange of such information. We argued that most such exchanges are naked restraints of trade. Because there are a few plausible explanations for limited kinds of exchanges that are unlikely to result in restraint on competition, we recommended that a “quick look” approach would be the appropriate standard. Moreover, we stressed that the focus of such an assessment should be on the merits of any purported justification rather than market shares or other indicia of market power.

Late in 2023, the DOJ sued Agri Stats for its program of collecting, analyzing and sharing confidential business information for pork packers and poultry and turkey integrators. Then in 2024, it sued RealPage for its information collection, processing, and rent recommendations to landlords. Both complaints were unclear as to the exact standard that the government was claiming applied to such information exchanges. What is clear is that the government is contending that the agreements to share such competitively sensitive information are in themselves unlawful restraints of trade regardless of whether there is a further agreement to fix prices or control output. This is an important step in the process of reclaiming a critical analysis of such agreements.

Most recently the DOJ submitted a Statement of Interest in the Pork Antitrust case where it more clearly invited the court to focus on the justification for the exchange and the market context in which it occurred rather than measuring market shares or other inferences of market power. Moreover, the Statement initially pointed out that the Supreme Court has held that agreements to exchanges competitively sensitive information can in themselves violate the antitrust law.

Leading decisions such as Todd v. Exxon have referred to the “rule of reason” as the standard and seemed to embrace a requirement of finding market power as a predicate to condemning such an exchange. The Statement is at pains (unnecessarily in my view) to advance a broad definition of the rule of reason as a flexible inquiry into the merits of the conduct at issue. Quoting from the Gypsum decision, however, the Statement stressed that the focus should be on how the exchange affects competition among the participants and in the market. Implicit in this approach is a rejection of the standard rule of reason model in which restraints are presumed lawful unless there is substantial market power.

Indeed, why would rivals, even if they did not dominate the market, exchange competitively sensitive information? Such an exchange would be likely to and is almost certainly intended to stabilize and restrain the competition between those rivals for customers in common. The primary function of any such exchange among rivals, however inclusive, is to provide a common understanding of the market to reduce or eliminate the incentives to compete.

The Statement of Interest in the pork case moves the government closer to recognizing that the appropriate standard is one that both presumes illegality and requires a legitimate explanation. Explicitly, it first emphasizes that exchanges of information inherently involve an agreement or understanding which satisfies that element of a section 1 case. Second, pointing to a long history of antitrust decisions, such exchanges can be in themselves illegal. They need not only serve as facilitating devices for express collusion on price, output, or customer allocation. This is a very important point to emphasize in relation to such agreements and is the basis on which the government has sued both Agri Stats and RealPage.

Third the Statement emphasizes that even if information is aggregated, it can still serve an anticompetitive function. Implicit, in this point is the proposition that the focus of analysis should be on why this information is being exchanged, which includes a variety of extrinsic factors. This leads to a section that identifies four factors that a court should consider. They are 1) the nature (“sensitivity”) of the information exchanged, 2) its granularity (how detailed is the information and how easily can a participant determine what its rivals are doing), 3) the public availability of the information, and 4) its contemporariness. Missing from this list is any recognition that legitimate bench marking projects might require exchanges of information that satisfy most of these criteria, but if this is a legitimate benchmarking project, there are ways to limit the granularity and contemporaneousness of the data.

The Statement regrettably failed to take a sufficiently strong and clear position that once the plaintiff established that an agreement to exchange confidential business information exists, that should create a rebuttable presumption that it constitutes a restraint of trade. Only if the defendant(s) can offer and provide proof of a plausible explanation for the exchange that does not involve a restraint should there be any need for a more nuanced investigation of the merits of the conduct. At that point, the four factors that the government identified are indeed relevant as is a direct rebuttal of the asserted justification for the exchange.

The legal doctrine governing information exchange continues to wrestle with two decisions from 1925 involving the maple flooring and cement industries that upheld anticompetitive information exchanges. Those case came during a time of “open competition” advocated by Herbert Hoover, then the Secretary of Commerce, and others to limit competition among business though use of information exchange and trade associations. Justice Stone, the author of both these opinions, was a friend of Hoover’s and apparently supported this kind of restraint on competition. A decade later, the Court essentially rejected these decisions. Justice Stone chose not to participate in that decision rather than dissent.

Nonetheless, the legacy of this early 20th century childlike faith in the potential that such exchanges might serve some public interest has continued to dog the development of a coherent doctrine. Deference to the dead-hand of the past leaves open too many paths for defendants and courts to justify or excuse harmful information sharing. The best hope is that the judge in either the Agri Stats or RealPage case (or better both) focus the decision on a presumption of illegality and require the defendants to bear the burden of persuasion that the presumption is inapplicable to the specific case. The Statement of Interest in the pork case does move the analysis a little closer to the appropriate standard.

In August, Judge Mehta of the Federal District Court in Washington, D.C., concluded in a careful and detailed opinion that Google had a monopoly in both the internet search market and the associated text advertising market. Google was found to have abused its market power by engaging in exclusionary conduct, including paying large sums of money to equipment makers, browser operators, and cell phone systems to retain this dominance. The opinion declared that while Google got its monopoly because of its “skill, industry, and foresight,” it then used unlawful tactics to entrench and reinforce that position. The decision also recognized the enormous cost of creating and maintaining an effective search engine, as well as a suggestion that the text advertising system involved substantial costs. Given the apparent durability of both these monopolies, the question that the Court now faces is finding an effective remedy.

This week, the Department of Justice (DOJ) is expected to file proposed remedies for this abuse of monopoly power. Several voices have weighed in on remedy design, including The Economist, in a leader titled “Dismantling Google is a terrible idea.” Divestiture of Chrome or Android should be avoided at all costs, argued the magazine, even if that means embracing behavioral remedies such as “limiting its ability to use its search engine to distribute its AI products,” or “mak[ing] public some of the technology that enables its search engine to work, such as its index of web pages and search-query logs.”

In two prior posts, we spelled out two alternative ways to remedy bottleneck monopolies. These monopolies are ones that connect otherwise competitive markets but for a variety of reasons are durable and unavoidable. Obvious examples include electric transmission systems, cell phone service, and natural gas pipelines. The internet world is also subject to a number of bottlenecks.

The Search and Text-Advertising Engines Are Bottleneck Monopolies

Google’s search engine stands between the great mass of users with questions and the entire internet’s resources. Its search engine functions to identify and classify potential responses to the question. The cost of creating the Google search engine was over $20 billion and it requires many billions annually to maintain and expand it. Only two other search engines exist, and one recent effort failed after massive investment. Of the survivors, Microsoft’s Bing has a 10 percent market share overall and the other, Yahoo, has less than 3 percent. Hence, neither is a significant competitor. Browser providers need to have one or more search engines easily accessible for users, and they can’t charge searchers for their searches.

Because the search engine is costly to create and maintain, the question is how to pay for this service. The text-advertising engine is the means for paying for all searches. Text advertisements are the textual lines appearing at the top of any search that implicates a good or service. The line links a searcher to the website of the advertiser that hopes to make a sale.

Google sells such access to advertisers as does Microsoft and Yahoo. Judge Metha found that the creation and maintenance of the text-advertising engine is also very substantial. But at the same time, the other search engines appear to have their own text-advertising engines. This at least suggests that such engines are more readily producible, and that Google’s dominance comes primarily from its control over the search engine. Both browser operators and advertisers agree that they have to use Google’s search engine. They accept the text search engine because that is the means by which Google is compensated. Google also shares that revenue with the browser operators.

The DOJ’s Theory of Harm and Implicit Remedy

The litigation seems to have focused primarily on the anticompetitive effects of the various exclusive dealing contracts that Google obtained to ensure the dominance of its search engine. These contracts involved multi-billion-dollar payments to cell phone makers (like Apple) and browsers (like Mozilla) to ensure Google search was the default option. Nominally, other options could be provided and were included in some browsers, but the effects of Google’s brand recognition and its placement in cell phone and computer browsers resulted in effective retention of a monopoly market share.

While the opinion focuses on the harms resulting from the exclusionary practices of Google, the underlying factual findings suggest that regardless of the specifics of the contracts at this point and for the foreseeable future, the Google search engine will retain its monopoly position. Removing the exclusionary terms from the contracts is unlikely to result in any significant change in the structure of the search engine market.

Perhaps the government belatedly recognized this situation and so tried to shift the focus of its case from an attack on the specific exclusionary effect of the contracts to a broader claim of monopolization. Judge Metha rejected that move because it came late in the litigation. This is somewhat similar to the government’s failure to think through its case against Microsoft in the late 1990s, which started as a challenge to the tying of the operating system to its browser but ultimately morphed into a broader challenge to Microsoft’s monopoly. The failure of the government in that case to have a remedy that would effectively address the monopoly bottleneck of the operating system explains why 25 years later, Window’s still has a monopoly share of computer operating systems and their applications.

The fundamental challenge is to find an effective remedy that will eliminate or significantly reduce the incentive to exploit the bottleneck monopoly and use it to exclude competition in the upstream or downstream markets that the monopoly serves. Eliminating at this point exclusionary contracts given the extraordinary costs of building and operating a search engine that would, at its best, basically duplicate the Google engine, is unlikely to affect the search market in the foreseeable future.

Consider the Alternatives

The central thesis of our prior posts was that where there was an unavoidable bottleneck monopoly, an effective remedy is to change the ownership of that monopoly in a way that would eliminate or greatly attenuate the incentives to exclude and exploit. We also recognized that the first best option would be to break up the monopoly. But in many cases, this is not a feasible option. We suggested that there were two other ways to reallocate ownership and control of the bottleneck. One way is to create a “condominium” that collectively owned the bottleneck, but each user had its own piece to use. The alternative is to move ownership to a “cooperative,” which would both own and operate the bottleneck. While a divestiture remedy is possible, we think that the more likely option is to have either a condo or cooperative own and operate the search engine. As suggested earlier, our assumption here is that the text engine is one that has little exclusionary power on its own and will be further weakened if the current case, in trial, concerning Google’s monopolization of the “ad stack” (e.g., ad server, ad network, and ad exchange) results in dissolution of that monopoly.

Option A: Divestiture

The historic response to monopoly expressly declared in the Standard Oil and American Tobacco cases is to break up the monopoly into separate competing firms. It is hard to imagine how a search engine could be subdivided, but it is possible to imagine that multiple entities could receive the right to use the existing engine, “hiving off” the search engine. Each might then have the right to undertake further development of the search engine. There probably would have to be some significant compensation to Google given its massive investment to date in the search engine. This would limit the number of browser or cell phone operators that could even consider a license.

A second concern would be brand loyalty. Would searchers, assuming that Google was allowed to retain its own version of the search engine, be willing to use alternatives in sufficient quantity that the result would be economically attractive? To recover the costs and make money, text advertising needs to be attractive to advertisers.

Finally, the engine itself needs continued work. This means that those entities that took the engine would need to develop additional capacity to perform those tasks, which is unlikely to be easy or inexpensive. This suggests that divested versions of the Google search engine would struggle to compete in the market.

It would also appear that if the text-advertising engine is currently a bottleneck monopoly in its own right, a licensing system for its use with the further right of each user to amend and improve its version would probably resolve this part of the monopoly. There is no brand loyalty for such engines. Moreover, as noted above, the pending Google ad tech monopoly case is likely to result in a further increase in competition in that area of technology.

Option B: A Condominium Solution

If the search engine is sufficiently distinct from the operation of browser and cell phone operating systems, then one remedy would be to transfer ownership of search engine to an entity owned by the various users, but with the on-going maintenance performed by a separate entity that contracts to provide this service to the owners. This is analogous to a condominium association contracting with a management company. Each owner of a condominium would pay for the managerial services and would be able to use the search engine.

The manager would have significant capacity, however, to exploit this system. If compensation were on a cost-plus basis, that might reduce the risk. An even more open system in which the manager’s task is only to review and implement proposed improvements developed by third parties might reduce further the risk of exploitation. The puzzle then would be how to compensate third parties for developments.

Overall, we are skeptical that a condominium-type structure would be a very effective solution to the monopoly bottleneck that the Google search engine presents.

Option C: Cooperative Solution

A cooperative type of organization would own the search engine itself and share the ongoing costs of its operation, based on usage by the participating enterprise. The cooperative would in turn either have its own staff to maintain the engine or it would contract with various third parties to supply necessary inputs. Each participant would be able to use the search engine as it saw fit and match it with whatever text-advertising system was most attractive given the customer base and technology of that entity.

A cooperative solution to the search engine monopoly is a much more promising solution than the options of injunction, divestiture, or condominium ownership. But we see two real risks and problems. First, there is a question of the incentives to innovate especially where some users would be advantaged over others. The risk is that if most distributors of the search engine are using the same vehicle, they may have a hard time supporting innovations that might favor some types of users, e.g., cell phones, over others, e.g., computers.

Second, as Judge Metha observed, and as The Economist points out, there is a possibility that AI may eventually make search engines obsolete or offer a very credible and open alternative. The judge concluded, however, that this potential was only that. There is no current or immediately foreseeable AI search system. The concern would be that if most search providers are participating in a cooperative that provides a search engine, they may have a collective disincentive to support or sponsor the potentially costly and time-consuming effort to develop an AI search system.

Conclusion

Finding an effective remedy for the monopoly created by Google search and text-advertising engines is a major challenge. Our concern is that the government has too narrowly focused on Google’s exclusionary contracts. Removing those contracts at this late date is unlikely to produce any significant change in the monopolization of these markets and potential for ongoing exploitation and exclusion. It is regrettable that the government did not initiate its case with an explicit focus on a remedy or remedies that could actually affect the future structure and conduct in this market. We have here examined three options that could dissipate the underlying monopoly power. Each has risks and problems, but each is a better alternative than a simplistic elimination of exclusionary contracts.

Washington Post columnist Eduardo Porter, in his recent piece, “Corporations are not destroying America,” seems to be taking cues on economic policy from his colleague Catherine Rampell. To Porter’s credit, he, contra Rampell, seems to actually read the materials he’s writing about. Yet the entire piece is emblematic of columns favored by the Post: ones that casually brush aside progressive policy ideas by dispatching with a straw man and infantilizing anyone to their left rather than engaging head on.

Porter takes issue with the “idea that American markets have become monopolized across the board, with dominant companies raising prices at will,” which he calls “ludicrous.” But that’s really not the point that progressives—or the Harris campaign, who Porter’s “memo” is addressed to—have been arguing. Could you find someone who thinks that every market in the country is overly concentrated with greedy fatcats leeching off the public? Absolutely. But it’s not the argument that progressives in the policy community and Harris have articulated.

The actual argument is not that every industry is overly concentrated, but that a number of key industries are, which enables opportunistic price gouging to ripple through key sectors of the economy and cause acute harms because of how critical those industries are. These are industries like meatpacking, airlines, credit-card issuing and processing, railroads, Internet search, ocean shipping, and baby formula. Porter can cite all the studies he wants that say overall concentration levels are not soaring or concerningly high and still not get to the substance of the argument. That said, there are numerous methodological and theoretical questions about measuring market concentration. But that’s hardly necessary here; the examples above are so obviously oligopolistic that there’s really no need for formal measurement.

Similarly, Porter simply misrepresents what opponents of corporate power claim big firms with pricing power are doing. He frames it as a matter of “dominant companies raising prices at will,” but the throughline in nearly all versions of progressives’ arguments is about companies leveraging particular disruptions, like inflation, as a smokescreen to exploit customers by raising prices in excess of the increased costs they’re incurring. Harris’s grocery price-gouging restriction has been much maligned by Rampell and other neoliberal pundits who usually either paper over that it only applies in emergencies (and only in the food industry) or elide it with a slippery slope “but what is an emergency?” distraction, preferring to hyper obsess over fringe cases when most of the time it will be pretty clear if we’re in an emergency; Harris’s plan specifically is inspired by the real-world exploitation of large groceries, as found by the FTC and revealed in the Kroger-Albertsons merger trial, during the last disaster.

Porter’s column also pointedly veers into an argument that narratives about “the monopolization of America often rests on evidence about corporate concentration at the national level. But the market relevant to consumers is, in many cases, local.” And that’s true to an extent, but Porter’s own example of hardware stores (directly following this) is a good demonstration of why this elides the harms to which progressives are trying to draw attention. Porter discusses “mom and pop” hardware stores vis-à-vis national chains Home Depot and Lowe’s (apparently he’s not a fan of ACE). But there are no mom-and-pop airlines or baby formula manufacturers or oil firms.

As far as the corporate big tech “Godzillas,” as Porter terms them, apparently they aren’t “squashing competition to reduce wages, keeping new rivals from entering their markets, and sticking it to consumers.” (Let’s ignore for a moment the very serious allegations that Uber and Amazon have suppressed the wages of their drivers. Or the recent verdict by a jury in Epic v. Google that Google overcharged app developers for transacting on the Play Store. Or the recent finding of a judge in U.S. v. Google that Google monopolized the search industry and the associated market for text advertising.) Rather, Big Tech’s fearsome power has come, per Porter, “first and foremost from deploying new technology and offering better value to customers.”

Presumably then, Facebook didn’t go buy out a bunch of other social media and networking websites and softwares. But it did. It bought ConnectU in June 2008, FriendFeed in August 2009, sharegrove in May 2010, Hot Potato in August 2010, Beluga in March 2011, Friend.ly in October 2011, and Instagram in April of 2012. Definitely not buying out competitors to sit on a huge pile of market share, just good old innovation!

And Amazon definitely got to where it is by besting its rivals through good old market competition! Except when it bought dozens of other online retailers and web service companies. Oh and when it artificially skewed its marketplace to disadvantage third party retailers in favor of Amazon’s own products, many of which were reproductions of other companies’ products.

Porter also seems to have overlooked the fact that Google acquired its way to power in the ad stack, gobbling up, among others, DoubleClick, Invite Media, and AdMeld.

The entire piece is vapid left-punching; Porter even actively agrees with the substance of the critiques against monopolists. For instance, this paragraph:

For sure, corporate consolidation has reduced competition in some markets. It was probably a bad idea to allow Whirlpool to take over Maytag in 2006, or to allow Miller to merge with Coors two years later. Hospital mergers deserve a much more skeptical view than they have received in the past. Let’s be careful about drug manufacturers buying out competitors for the purpose of killing a potential competing drug.

Yes, there is discourse about the American economy becoming more consolidated writ large, but the core of the debate is about intra-industry dynamics where market power creates unique opportunities for profit at the expense of consumers. Like when pharmaceutical companies buy out a firm working on a competing treatment. In sum, we have yet another piece to file away in the classic genre of “WaPo doesn’t have anything substantive to add, but feels the need to put down uppity leftists.” (It’s only gotten worse after new data revisions showed an even sharper uptick in corporate profits than earlier data had indicated.)

The last thought Porter offers is that “taking a wrecking ball to big business in the service of a rickety theory of harm will do everyday Americans no good.” What is the wrecking ball? Who is proposing to destroy major corporations?

The entire case laid out in this “memo” is that Harris, at progressives’ behest, is calling for leveling all large corporations. But Porter would do well to remember that the story of Rampell’s he links to in order to outline the consequences of this “wrecking ball” literally lies about what Harris’s pricing gouging law narrowly targeted at suppliers in the food industry (as opposed to all large companies) would look like. There are no “price controls” in the proposal, contrary to Rampell’s suggestion; food suppliers could justify price hikes during the next crisis so long as they were cost-justified. Rampell says Harris’s plan is likely to be modeled after a bill from Senator Warren (D-MA) that would give the FTC power to punish firms for price gouging.

As a justification for why such a law would be disastrous, Rampell says that “the legislation would ban companies from offering lower prices to a big customer such as Costco than to Joe’s Corner Store, which means quantity discounts are in trouble.” No, it doesn’t. There is absolutely no prohibition against quantity discounts. Rampell is, at best, warping this line stating that one standard that would give a firm “unfair leverage,” which would make it presumptively in violation of the statute, is when it “discriminates between otherwise equal trading partners in the same market by applying differential prices or conditions.”

If two firms are buying vastly different quantities of something, they are not “otherwise equal trading partners” of that supplier. What that line actually means is that if Joe’s Corner Store and Bob’s Corner Store both order identical shipments of widgets but Widgets Incorporated charges a much higher rate to Joe than Bob, then that is unfair pricing.

This is not the first time that Rampell has grossly misrepresented what Warren’s legislation says. Back in March, she said that it, and a similar bill from Senator Casey (D-PA), would be “[f]orbidding companies from changing the prices and sizes of everyday products without government say-so.” Neither bill said anything remotely like that. The fact of the matter is that Catherine Rampell is so committed to lashing out at the left that she either doesn’t bother to read the things she’s complaining about or is happy to just outright lie. Whatever the case may be, Porter should look elsewhere for insights about the economy.

Dylan Gyauch-Lewis is a Senior Researcher at the Revolving Door Project. She leads RDP’s Economic Media Project.

The FTC is seeking a preliminary injunction to prevent two of the country’s largest supermarket chains, Kroger and Albertsons, from merging. The case was heard in the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon, where U.S. District Judge Adrienne Nelson, a former Oregon Supreme Court justice, will soon render a verdict.

The merger would make Kroger-Albertsons the second largest retail store after Walmart. The FTC alleges that, in hundreds of local grocery and labor markets, the merger increases Kroger’s market share to a degree sufficient to activate the structural presumption against the merger. Kroger, unsurprisingly, has advanced various standard arguments in favor of mergers: that it is necessary to compete with even larger retailers (in this case, Walmart), will result in lower prices for consumers, and that any anticompetitive harm would be offset by the divestiture plan built into the merger.

As an initial matter, it is unclear whether the central mission of the Sherman Act—to promote healthy competition—is compatible with Kroger’s argument that the merger is necessary to compete with Walmart. While it is undoubtedly true that Walmart is a corporate behemoth whose very existence is an existential threat to competition, it hardly follows that allowing a merger that creates a second behemoth is the best way to reign in the first. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that the drafters of the Sherman Act could even comprehend a corporation as large as Walmart in the first place—and even if they could, it is hard to imagine that they would accept a second, equally large corporation as a legitimate solution.

Kroger’s Defenses Are Unavailing

Putting this aside for a moment though, it is worth taking a closer look at some of the arguments Kroger-Albertsons have advanced to support the merger. First, Kroger has tried to portray Albertsons as a failing firm. Yet testimony has established that Albertsons is not a failing or flailing firm—and in fact, is far from it. Albertsons CEO Vivek Sankaran, testifying in front of Congress in 2022, stated that the firm is in “excellent financial condition” with “more than sufficient resources to continue” with their current plan. Albertsons has admitted that, if the merger does not go through, they have no plans to close any stores. In FY 2023 securities filings, Albertsons told investors that it was “pleased” with their reported $1.3 billion net income. Albertsons COO Susan Morris has also testified that the company is still on track to achieve its savings goals whether or not the merger goes through. What then explains Albertsons leadership’s eagerness to merge? The answer is hardly surprising—their executives have testified that their private equity backers stand to gain tens of millions of dollars in parachute payments should the merger be approved.

Second, Kroger argues that the merger would not produce anticompetitive effects due to the divestiture plan built into the acquisition. The plan is to sell hundreds of stores in overlapping grocery markets to C&S, a wholesale grocer, which, according to Kroger, would mitigate any anticompetitive harm. As the FTC has repeatedly pointed out throughout the trial, there are more than a few reasons to be suspicious of this argument.

The Court should be skeptical of this remedy, as every party in this transaction has a failing record of making divestiture work. For example, in Albertsons’ 2015 acquisition of Safeway, 146 stores were divested to Haggen. Haggen filed bankruptcy within months, and shortly thereafter, Albertsons reacquired 54 of the stores it had previously sold. This is not the only reason for skepticism. As was revealed at trial, Alona Florenz (C&S Senior VP of corporate development and financial planning), writing to a Bain consultant, stated “just be careful with FTC. We want to say we can run them.” It doesn’t take a genius to read the subtext—C&S wants to say that they can run the stores so that, after the merger is approved, they can turn around and gut them for profit.

This interpretation is further supported by the economic realities inherent in the divestiture plan. C&S is primarily a wholesale grocer, meaning that its primary mode of business is selling in bulk to grocers, not operating stores that sell groceries to consumers. It is extremely unlikely that C&S has the infrastructure or know-how to successfully operate hundreds of grocery stores across the country that are acquired simultaneously. Further, it was revealed during discovery that C&S officials themselves believe that they are buying Kroger’s worst stores. Not only have they been caught saying the quiet part out loud, the price that C&S would pay is itself revealing: the deal is priced close to the value of the real estate alone, suggesting that C&S could easily sell off the stores for close to what it paid.

You may be thinking: even if C&S doesn’t stand to lose much on the deal, what’s in it for them? Fortunately, one need not look far for an answer. When Price Chopper and Tops, (two grocery stores) merged, C&S acquired certain stores as part of the divestiture plan. As they have done here, C&S was happy to tell the FTC that they planned to use the newly acquired stores to robustly compete with the newly merged firm. But what actually happened? C&S operated some of the stores at a loss while using others as leverage to increase profits in its wholesale business—its primary money-maker. They sold many of the recently acquired stores to their wholesale customers, who, in return, extended their lucrative contracts with C&S.

As further evidence of C&S’s true intentions, the acquisition price of the divested stores is essentially equal to the value of the real estate alone. And in a previous merger, after telling the Court that they would use stores acquired in a divestiture plan to compete with the merged firm, they turned around and sold enough stores to ensure that their wholesale profits, their primary source of revenue, would eclipse the losses from the self-proclaimed dud firms they acquired and retained. What possible reason would Judge Nelson have to believe that this would go any differently? And to top it off, even if the divestiture plan went exactly as Kroger and C&S say it would, it would fail to cure the anticompetitive harm in hundreds of local markets across the country.

Beware of Dynamic Pricing

Beyond the inadequacy of the divestiture plan, the FTC has raised other concerns that may be even more serious—especially for consumers. In 2018, Kroger began rolling out “digital price tags,” which allow the company to change retail prices in real time. Several lawmakers have expressed concern that these digital price tags could be used to facilitate dynamic pricing, whereby the price charged depends on the identity of the consumer making the purchase. The digital price tags come equipped with cameras, which use the vast amounts of data to which Kroger has access to change the price of an item depending on who the camera sees looking at the shelf. If the merger were to go through, Kroger would acquire all Albertsons’ data about their consumers, which would greatly increase the efficiency with which Kroger can price discriminate.

Kroger, of course, has steadfastly denied that the new technology will be used to raise prices. These denials are a staple of merger cases—firms poised to merge have consistently argued that they won’t raise prices, and far too often, courts have been content to take them at their word. Here, should the merger go through, Kroger has promised to invest $1 billion to keep prices low. Government attorneys correctly pointed out that, not only are these promises completely unenforceable, but history has shown that they are utterly meaningless, as post-merger firms have consistently broken these promises without consequence. Corporations such as Kroger have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders, not to their customers. If they see opportunities to raise profits, this duty requires them to pursue it—consumers be damned. Beyond history, Kroger itself has proven to be untrustworthy—in the course of these proceedings, they were forced to admit that they had engaged in price gouging on consumer staples such as milk and eggs in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Worker Welfare Matters Too

Beyond hurting consumers, the merger also harms employees. Kroger and Albertsons currently employ around 710,000 people across about 5,000 stores nationwide. Currently, unions can bargain separately with Kroger and Albertsons, and thus have greater leverage to advocate for increased wages and other protections for their workers. Should the merger go through, unions will lose this critical leverage, and would again be subjected to the whims of Kroger’s leadership. Kroger’s attorney, the aptly named Matthew Wolf, told Judge Nelson that “[Kroger] will preserve the unions.” As with his promise that the merger would lead to lower prices, taking Mr. Wolf at his word would be no wiser than taking the word of an actual wolf who tells the farmer that he will diligently guard the hen house.

Judge Nelson should grant the FTC’s preliminary injunction blocking the merger between Kroger and Albertsons. Albertsons is a healthy firm whose presence in the market is essential to competition, and their desire to merge is motivated by the fact that their executives stand to make tens of millions of dollars should it be consummated. The divestiture plan, even if it plays out exactly as Kroger says it would, is inadequate to mitigate the anticompetitive harm that would result from the merger. C&S, the acquirer, has openly stated that it is taking on Kroger’s worst firms, has a strong economic incentive to pawn off the newly acquired firms to secure greater profits in its primary revenue source as a wholesaler, and has a known track record of doing exactly that. The acquisition, which would include all of Albertsons’ consumer data, would allow Kroger to exponentially increase the sophistication and efficiency of their dynamic pricing regime. And, after admitting to price gouging amidst a global pandemic, Kroger offers nothing more than its legally unenforceable word that it won’t use the immense increase in market share to raise prices or harm workers. This merger will harm competition, consumers, and workers. The Court should reject it.

Corey Lipton is in his final year of the JD/MPP program at the University of Michigan.