Just weeks after a series of high profile train derailments headlined by the disaster in East Palestine, Ohio, the Surface Transportation Board (STB) decided to double down on the current railroad oligopoly. The STB approved a merger between Canadian Pacific Railway and Kansas City Southern Railway Company, cutting the number of major “Class I” rail companies in the United States from seven down to six. This decision is diametrically opposed to the public interest and seriously undermines trust in rail regulators.

The merger approval clearly violates President Biden’s Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, which explicitly directed the STB to begin rulemaking to make it harder for railroads to engage in anticompetitive practices. The order instructed the chair to “consider rulemakings pertaining to any other relevant matter of competitive access, including bottleneck rates, interchange commitments, or other matters.” Instead, the STB has abetted concentration that makes it harder to regulate.

Because the decision goes against Biden’s overarching competition agenda, the Revolving Door Project today released a letter with RootsAction and FreedomBLOC calling for President Biden to relieve Martin Oberman from his chairmanship at the STB. This backtracking requires a major course correction that can only be achieved by a change in leadership.

Besides being antithetical to one of the defining policies of the Biden administration, the STB’s decision breaks from other parts of the administration. As the FTC and DOJ Antitrust Division have redoubled their efforts to push back on monopolization across the economy, the STB approved the first big freight-rail merger since the 1990s. But it’s not just the FTC and DOJ going in the opposite direction of the STB; Secretary Pete Buttigieg and his Department of Transportation have recently raised their scrutiny of transportation mergers, highlighted by blocking airline consolidation.

And while Buttigieg has not explicitly chimed in on the rail merger, other regulators did, warning the STB against approval. The DOJ Antitrust Division warned against the merger, saying it could “empower the merged railroad to deny shippers access to the lowest cost or fastest end-to-end routings. […] The railroad sector in particular, with its relatively high fixed and sunk costs, often enjoys substantial structural entry barriers and advantages that may facilitate or incentivize anticompetitive behavior.”

Additionally, a majority of the Federal Maritime Commission opposed the merger, arguing that “the proposed consolidation does not ensure that the anticompetitive effects of the transaction outweigh the public interest in meeting significant needs.” As I’ve written before, the FMC has a history of serious dovishness on consolidation, making such a strong position all the more notable. The merger is even being opposed by another railroad; Union Pacific is suing to block the STB’s decision.

Besides undermining the administration’s broader policy agenda, the STB’s decision will also undermine safety in the rail industry. What’s the basis for such a strong claim? The STB’s own analysis found the merger would “slightly increase” risks of derailments. Taking their analysis at its word, even slight increases in such risks seem folly after Norfolk Southern set East Palestine ablaze with a single derailment. That incident highlighted how underequipped and unprepared regulators were to deal with any derailment. Allowing an increase in that risk just to enable more corporate profits is a bad trade for the American people.

Another cost of the merger is less effective oversight. As I wrote in The Sling in March, “More industry concentration makes effective regulation harder. As firms increase in size, they gain more and more of a resource advantage over their regulators. One behemoth corporation can often hire more lawyers and cultivate more relationships with lawmakers in order to obfuscate enforcement measures than multiple smaller ones could.”

Of course, there are corporate-friendly defenders of the merger. The Economist argued that the merger “may end up enhancing competition” because the two rail companies do not directly compete—there are no overlapping tracks—and because the merged entity “will provide the first train lines running from Canadian ports through the heart of the United States into Mexico. This is poppycock: A merger that doesn’t involve head-to-head competitors can still be harmful if it enables the merged firm to engage in anticompetitive behavior such as blocking rival’s market access.

Indeed, The Economist gives the game away in the very next paragraph, admitting the rail “industry is also consolidating, which leads to greater pricing power.” There’s only one consolidation going on and it’s the one they’re seeking to defend. If pricing power will increase simply by virtue of consolidation, that means that even though the current lines don’t overlap, the merger facilitates anti-competitive behavior. Full stop.

This is exactly the point the DOJ made in its statement to the STB as well. As they put it:

Even beyond the elimination of head-to-head competition, mergers that increase market power can harm competition in several ways. The merger can empower the merged railroad to deny shippers access to the lowest cost or fastest end-to-end routings. Likewise, in the absence of a complete refusal to interchange traffic, mergers may enable firms to foreclose competition in other ways, such as raising costs for their rivals through control over inputs or access. Such mergers also can create a more conducive structure for post-merger coordination between direct competitors by facilitating communication or discipline through the new integrated asset. The railroad sector in particular, with its relatively high fixed and sunk costs, often enjoys substantial structural entry barriers and advantages that may facilitate or incentivize anticompetitive behavior. For example, railroads may anticompetitively refuse to interchange traffic and/or favor the newly integrated company’s long-haul route over a more efficient joint line route.

Four of the other five Class I railroads agree, having opposed the merger because of how it would enable the new CPKC to block competitors from accessing important junctions, particularly Houston. This comes after earlier concerns from Union Pacific and BNSF around the Houston terminal. In short, the massive market power the merger grants CPKS will allow for the firm to undermine competition by blocking other railroads from readily accessing interchanges and other rail that Kansas City Southern currently shares with other shippers. Despite the two firms not directly competing in their current routes, the vertical integration creates the opportunity to force business away from other railroads because of the degree of control over their competitors’ ability to operate competing routes.

The Canadian Pacific-Kansas City Southern merger undermines administration policy and directly contributes to further anticompetitive practices in the rail industry. It is also likely to cause worse service, job cuts, weaker oversight, and higher prices, among other harms. President Biden should heed his Transportation Department, Justice Department, and Federal Maritime Commission and appoint new leadership at the STB.

Dylan Gyauch-Lewis is a researcher at the Revolving Door Project.

Paradigm change is hard. It took over a year to overcome significant ridicule from neoliberal economists and pundits for the evidence to be so compelling as to flip the consensus on the causes of inflation. Business press outlets from the Wall Street Journal to Bloomberg to Business Insider now perceive what some heterodox economists have recognized for a while—that companies in concentrated industries were exploiting an inflationary environment to hike prices in excess of any cost increases they were incurring. (Alas, The Economist refuses to see the light.) Even Biden’s director of the National Economic Council, Lael Brainard, refers to this bout of inflation as a “price-price spiral, whereby final prices have risen by more than the increases in input prices.”

It’s hard to assign credit for flipping the script, but a few brave economists deserve mention. Isabella Weber, an economist at the University of Massachusetts, published a provocative article, co-authored with Evan Wasner, titled “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?” They explain how firms with market power only engage in price hikes if they expect their competitors to follow, which requires an implicit agreement that can be coordinated by sector-wide cost shocks and supply bottlenecks.

Josh Bivens of Economic Policy Institute debunked the neoliberal claim that wage demand was driving inflation, showing instead that corporate profit was responsible for more than one third of the price growth. Mike Konzcal and Niko Lusiani of the Roosevelt Institute demonstrated that U.S. firms that increased markups in 2021 the most were those with the higher mark-ups prior to the economic shocks, an indication that concentration was facilitating coordination. (If one were to expand the list of thought influencers beyond economists, you’d have to start with Lindsay Owens of the Groundwork Collaborative, who has been analyzing what CEOs say on earnings calls since the onset of inflation.)

With the new consensus, we need think creatively about attacking inflation. We have more than one tool at our disposal. Rate hikes might ultimately slow inflation, but at enormous social costs, as that mechanism requires putting people out of work so they have less money to spend. What’s worse, rate hikes are regressive, with the most vulnerable among us bearing the largest costs. Solving the inflationary puzzle calls for a scalpel not a chainsaw: We need to identify the industries that contribute the most to inflation (e.g. rental, electricity, certain foods), and then tailor remedies that attack inflation at its source. To use one analogy, it wouldn’t make sense to bulldoze a house because a fire was burning in one room. You’d find that room and put out the fire. I am calling for seven policies in particular.

(1) More Bully Pulpit. The President should use the bully pulpit more—recall JFK’s turning back steel price hikes in 1962. Biden called out junk fees in his state of the union address, causing airlines to remove unwarranted fees for families sitting together. Clearly, Biden can’t hold a press conference about a misbehaving industry daily. But he has not come close to tapping this well.

(2) More Congressional Hearings. Congress should hold hearings to call executives to account for price gouging. Although Congress has held hearings with experts, they have yet to summon the CEOs of industries employing massive price hikes, seemingly in coordination—as if they were some tacit agreement to raise prices in unison. I’d start by calling the CEOs of the packaged food makers, PepsiCo, Unilever, and Nestlé, who bragged last week to investors about record profits, massive price hikes, and enduring pricing power.

(3) The FTC to the Rescue. The FTC should investigate firms for announcing current or future price hikes (or capacity reductions) during earnings calls under the agency’s unique Section 5 authority to police “invitations to collude.” These cases of “tacit collusion” are much harder to prosecute under the Sherman Act. If the FTC were to publicly announce an investigation into a firm or industry—airlines (admittedly outside the FTC’s jurisdiction) or retail would be a good place to start—it would force CEOs economywide to exercise more caution about sharing competitively sensitive information on earnings calls.

(4) Limits on Concentrated Holdings: The cost of shelter makes up a significant share of the core CPI. Cities or states should move to limit the holdings of any individual firm within a given census tract. My OECD paper, co-authored with Jacob Linger and Ted Tatos, showed the nexus between rental inflation and concentration in Florida. A natural cap for a single owner would be five or ten percent of all rental properties in a neighborhood. Raising interest rates, our default anti-inflation tool, perversely puts home ownership out of reach of millions of families, driving them to the rental markets, which bids up rental rates, which is one of the primary drivers of inflation.

(5) Price Controls Should Be on the Table. Price controls are the ugly stepsister in economics. But when backed by a public campaign, they have proven to be effective. Congress imposed price caps for insulin copays in the Inflation Reduction Act, but only for those patients covered by Medicare. Insulin makers, beginning with Eli Lilly, saw the writing on the wall, and voluntarily imposed the $35 cap on all patients. So long as caps are sparingly used in mature industries, the standard investment concerns of economists should be mitigated. The lesson from insulin is that the mere talk of price controls can induce an industry to temper their enthusiasm for price hikes.

(6) Government Provisioning. The threat of government provisioning is another lever that may force private industry to behave. To wit, California offered a $50 million contract to makes its own insulin, which coincided with Eli Lilly, Sanofi and Novo Nordisk preemptively reducing their prices. This playbook could be used in other industries where inflation remains stubbornly high. We can anticipate libertarians screaming “socialism,” but if the cost of inaction is more rate hikes and unemployment, I’d take the libertarian jeers any day.

(7) Fix Antitrust Law. Congress should amend the Sherman Act to give the DOJ, state attorneys general, and private enforcers a better shot at policing tacit collusion among firms in concentrated industries. Courts have implicitly adopted the notion that oligopolistic interdependence is just as likely to achieve prices inflated over competitive conditions as agreement, and so “merely” alleging or putting forward evidence of parallel pricing, excess capacity, and artificially inflated prices is insufficient to prove agreement under Section 1. But why should we presume that it is just as easy to maintain artificially inflated prices tacitly than through agreement?

Congress should flip the presumption. In particular, Section 1 of the Sherman Act should be amended so that the following shall create a presumption of agreement: Evidence of parallel pricing accompanied by evidence of (a) inter-firm communications containing competitively sensitive information, or (b) other actions that would be against the unilateral interests of firms not otherwise colluding, or (c) prices exceeding those that would be predicted by fundamentals of supply or demand. Moreover, the Sherman Act should be amended to permit courts to sanction corporate executives who participated in any price-fixing conspiracy upon a guilty verdict, by barring the executives from working in the industries in which they broke the law, either indefinitely or for a period of time.

Industrial organization gatekeepers like to poo-poo the idea of using competition tools to attack inflation, noting that antitrust moves too slowly. This is needlessly pessimistic. It bears noting that none of the seven remedies suggested here involve bringing a traditional antitrust case against a set of firms pursuant to the Sherman Act. The common thread that binds the first six remedies is inducing a short-run shift in industry behavior. A forced divestiture of rental properties over a holding limit would inject downward-pressure on rents in the short run. CEOs don’t want to be called out by the president or called to testify before Congress to explain their record-breaking profits attributable to massive price hikes above any cost increases. A public investigation by the FTC into invitations to collude via earnings calls would also have an immediate effect on CEOs. Nor would CEOs take lightly to being barred for life from an industry for participating in a price-fixing scheme.

The seven interventions outlined here will require an all-of-government approach. Biden should create a task force to carry out these policies and issue an executive order to signal his seriousness to other agencies. There are two paths for Biden’s legacy: Do nothing about inflation and leave it to the Fed to engineer a recession that likely ends his presidency, or grab the reins himself. With the new consensus emerging that profits (and not wage demands) are driving inflation, the time has come to change our approach.

As the frontline against illegal monopolies and deceptive corporate behavior, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has a critical role to play in building an economy that works for consumers and small businesses. Since becoming FTC Chair, Lina Khan’s efforts to rein in anti-competitive behavior and protect consumers has been met with fierce resistance from powerful special interests and hostile editorials in the The Wall Street Journal.

Unfortunately, given the FTC’s role in combating unfair corporate behavior, this pushback is to be expected. I should know: I had the privilege of being an FTC commissioner, serving in both the Clinton and Bush administrations. I’ve seen fair, and unfair, criticism targeted at Republican and Democratic FTC chairs alike.

As a commissioner, I served under Chair Tim Muris, who was appointed by George W. Bush and whose aggressive stewardship of the agency resembled in many ways the current leadership of Chair Lina Khan. While at the helm of the FTC, Chair Muris pursued one of the most aggressive regulatory agendas of any Bush-appointed agency heads. His agenda was assisted by his chief of staff, Christine S. Wilson, who went on to be appointed to the FTC by Donald Trump.

Despite this history, Wilson made big news when, as part of her resignation announcement, she attacked Chair Khan’s “honesty and integrity” and accused her of “abuses of government power” and “lawlessness.” This turned many heads in Washington, particularly mine because of how detached this viewpoint was from my prior experience of serving at the FTC under Wilson’s own stewardship of the agency.

In his 2021 Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, President Biden acknowledged that “a fair, open, and competitive marketplace has long been a cornerstone of the American economy.” Unfortunately, corporate concentration has grown under both parties for many years, especially in the technology industry. It is fortunate, and past time, to see the White House, the FTC, Department of Justice, and other agencies working to swing back the pendulum and reinvigorate competition in the American economy.

Despite the ongoing crisis of corporate concentration, Ms. Wilson took objection to an antitrust policy statement the FTC adopted in November and to Chair Khan’s statements in favor of strong enforcement. I found this odd having seen up close Ms. Wilson zealously advance Chair Muris’s enforcement agenda. In office, Muris “challenged mergers in markets from ‘ice cream to pickles,’” as the Wall Street Journal once noted, including in the technology industry, where Lina Khan has devoted significant attention.

During his tenure, Muris used the power available to him as Chair on behalf of consumers and for the good of the economy. He evolved the theory behind FTC regulatory authority so he could take new action to protect consumers—like creating the DO NOT CALL registry—over frivolous legal objections by the telecommunications industry. Like Khan, he coordinated with the DOJ to ensure that they were addressing anticompetitive behavior.

Ms. Wilson claims that Chair Khan should have recused herself from a Facebook acquisition case because of opinions she had expressed as a Congressional staffer. But both a federal judge and the full Commission found no basis to these claims of impropriety, and it is clear that Chair Khan had no legal or ethical obligation to recuse in this case. FTC Commissioners including Khan, like judges, are required to set their personal opinions aside and evaluate cases on the merits, and they do. The FTC Ethics Guidelines tells commissioners to ”not work on FTC matters that affect your interests: financial, relational, or organizational.” When it comes to ethics guidelines, it doesn’t get any plainer than that, and Chair Khan’s participation in the case clearly does not violate these guidelines.

In a hyper-partisan environment, Ms. Wilson’s attacks on the FTC’s credibility appear to me as an attempt to slow antitrust enforcement and ultimately obfuscate Chair Khan’s pro-consumer agenda.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which lobbies against pro-consumer regulations, sent an open letter to Senate oversight committees demanding an investigation of “mismanagement” at the FTC, including congressional hearings. No wonder the Chamber is upset. The Biden Administration is taking the crisis of corporate concentration seriously and is taking steps to bolster antitrust and consumer protection enforcement. That’s a development American consumers should cheer, because when corporate consolidation rises, competition is inevitably diminished, leading to higher prices and fewer choices for consumers.

Fortunately, Chair Khan is building on the legacy of strong leaders like Muris to build an economy that works for consumers, not harmful monopolies. Ultimately, she will be remembered for that and not cynical, distracting attacks on her.

Sheila Foster Anthony, a FTC commissioner from 1997-2003, previously served as Assistant Attorney General for Legislation at the U.S.Department of Justice. Prior to her government service, she practiced intellectual property law in a D.C. firm.

Over the last 40 years, antitrust cases have been increasingly onerous and costly to litigate, yet if plaintiffs can prevail on one single issue, they dramatically enhance their chances of obtaining a favorable judgment. That issue is market definition.

Market definition is straightforward to explain because it’s just what it sounds like. Litigants and judges must be able to delineate the market in question in order to determine how much control a corporation exercises over it. Defining a relevant market essentially answers, depending on the conduct courts are analyzing, whether computers that run Apple’s MacOS operating system or Microsoft Windows are in the same market or, similarly, if Coca-Cola competes with Pepsi.

A corporation’s degree of control over any particular market is then typically measured by how much market share it has. In antitrust litigation, calculating a firm’s market share is the simplest and most common way to determine a firm’s ability to adversely affect market competition, including its influence over output, prices, or the entry of new firms. While the issue may seem mundane and even somewhat technocratic, defining a relevant market is the single most important determination in antitrust litigation. Indeed, many antitrust violations turn on whether a defendant has a high market share in the relevant market.

Market definition is a throughline in antitrust litigation. All violations that require a rule of reason analysis under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, such as resale price maintenance and vertical territorial restraints, require a market to be defined. All claims under Section 2 of the Sherman Act require a relevant market. And all claims under Sections 3 and 7 of the Clayton Act require a relevant market to be defined.

Defining relevant markets stems from the language of the antitrust laws. Section 2 of the Sherman Act states that monopolization tactics are illegal in “any part of the trade or commerce[.]” Sections 3 and Section 7 prohibit exclusive deals and tyings involving commodities and mergers, respectively in “any line of commerce or…in any section of the country[.]” “[A]ny” “part” or “line of commerce” inherently requires some description of a market that is at issue.

As I more thoroughly described in a newly released working paper, the process of defining relevant markets has a long and winding history stemming from the inception of the Sherman Act in 1890. Between 1890 and 1944, the Supreme Court took a highly generalized approach, requiring as it stated in 1895, only a description of “some considerable portion, of a particular kind of merchandise or commodity[.]” In subsequent cases during this initial era, the Supreme Court provided little additional guidance, maintaining that litigants merely needed to provide a generalized description of “any one of the classes of things forming a part of interstate or foreign commerce.”

In 1945, after Circuit Court Judge Learned Hand found the Aluminum Company of America (commonly known as ALCOA) liable for monopolization in a landmark case, the market definition process started to become more refined, primarily focusing on how products were similar and interchangeable such that they performed comparable functions. At the same time market definition took on more complexity, antitrust enforcement exploded and courts became flooded with antitrust litigation. Given the circumstances, the Supreme Court felt that it needed to provide litigants with more structure to the antitrust laws, not only to effectuate Congress’s intent of protecting freedom of economic opportunity and preventing dominant corporations from using unfair business practices to succeed, but also to assist judges in determining whether a violation occurred. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Supreme Court repeatedly expressed its frustration that there was no formal process for litigants to help the courts define markets.

It took until 1962 for the Supreme Court to comprehensively determine how markets should be defined and bring some much-needed structure to antitrust enforcement. The process, known as the Brown Shoe methodology after the 1962 case, requires litigants to present information to a reviewing court that describes the “nature of the commercial entities involved and by the nature of the competition [firms] face…[based on] trade realit[ies].” With this information, judges are required to engage in a heavy review of the information they are presented with and make a reasonable decision that accurately reflects the actual market competition between the products and services at issue in the litigation.

Constructing a relevant market for the purposes of antitrust litigation using the Brown Shoe methodology can be made using a variety of commonly understood and accessible information sources. For example, previous markets in antitrust litigation have been constructed from reviewing consumer preferences, consumer surveys, comparing the functional capabilities of products, the uniqueness of the buyers or production facilities, or trade association data. In a series of cases between 1962 to the present, the Supreme Court has rigorously refined its Brown Shoe process to ensure both litigants and judges had sufficient guidance to define markets. Critically, in no way did the Supreme Court intend for its Brown Shoe methodology to restrict or hinder the enforcement of the antitrust laws, and the fact that the process relies on readily accessible and commonly understood information is indicative of that goal.

But 1982 was a watershed year. Enforcement officials in the Reagan administration tossed aside more than a decade of carefully crafted jurisprudence from the Supreme Court in favor of complex, unnecessary, and arbitrary tests to define a relevant market. The new test, known as the hypothetical monopolist test (HMT), which is often informed by econometric models, asks whether a hypothetical monopolist of the products under consideration could profitably raise prices over competitive levels. It is tantamount to asking how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. They primarily accomplished this economics-laden burden through the implementation of a new set of guidelines that detailed how the Department of Justice would analyze mergers, determine whether to bring an enforcement action, and how the agency would conduct certain parts of antitrust litigation, one of those aspects being the market definition process.

From the 1982 implementation of new merger guidelines to the present, judges and litigants, predominantly federal enforcers, have ignored the Brown Shoe methodology and instead have embraced the HMT and its navel-gazing estimation of angels. As a result, courts now entertain battles of econometric experts, over what should amount to a straightforward inquiry.

As scholar Louis Schwartz aptly described, the relegation of the Brown Shoe methodology and its brazen replacement with econometrics under the 1982 guidelines represented a “legal smuggling” of byzantine economic criteria into antitrust litigation.

Besides facilitating the de-economization of antitrust enforcement, abandoning the econometric process would have other notable benefits. First, relying entirely on the Brown Shoe methodology would restrict the power of judges, lawyers, and economists by making the law more comprehensible to litigants. Giving power back to litigants would contribute to making antitrust law less technocratic and abstruse and more democratically accountable. For example, in some cases, economists have great difficulty explaining their findings to judges in intelligible terms. In extreme cases, judges are required to hire their own economic experts just to decipher the material presented by the litigants. Simply stated, the law is not just for economists, judges, or lawyers; it is also for ordinary people. Discarding the econometric tests for market definition facilitates not only the understanding of antitrust law, but also how to stay within its boundaries.

Second, reverting to the Brown Shoe methodology would make antitrust law fairer and promote its enforcement. The only parties that stand to gain from employing econometric tests are the economists conducting the analysis, the lawyers defending large corporations, and corporations who wish to be shielded from the antitrust laws. Frequently charging more than a $1,000 dollars an hour, economists are also extraordinarily expensive for litigants to employ, creating an exceptionally high barrier to otherwise meritorious legal claims.

Since 1982, market definition in antitrust litigation has lingered in a highly nebulous environment, where both the econometric tests informing the HMT and the Brown Shoe methodology co-exist but with only the Brown Shoe methodology having explicit approval by the Supreme Court. Even in its highly contentious and confusing 2018 ruling in Ohio v. American Express, the Supreme Court did not mention or cite the econometric processes currently employed by courts and detailed in the merger guidelines to define relevant markets. In fact, in a brief statement, the Court reaffirmed the controlling process it developed in Brown Shoe, yet lower courts continue to cite the failure of plaintiffs to meet the requirements of the econometric market definition process as one of the primary reasons to dismiss antitrust cases. Putting it aptly, Professor Jonathan Baker has stated that the “outcome of more [antitrust] cases has surely turned on market definition than on any other substantive issue.”

While the econometric process is not the exclusive process enforcers use to define markets in antitrust litigation and is often used in conjunction with the Brown Shoe methodology, completely abandoning it is critical to de-economizing antitrust law more generally. Since the late 1970s, primarily due to the work published by Robert Bork and other Chicago School adherents, economics and economic thinking more generally have become deeply entrenched in antitrust litigation. Chicago School thought has essentially made antitrust enforcement of nearly all vertical restraints like territorial limitations per se legal, and since the 1970s, the Supreme Court has overturned many of its per se rules. Contravening controlling case law on vertical mergers, Chicago School thinking has resulted in judges viewing them as almost always benign or even beneficial and failing to condemn them by applying the antitrust laws. Dubious economic assumptions have significantly restricted antitrust liability for predatory pricing, a practice described by the Supreme Court in 1986 as “rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.” As a result, economic thinking and econometric methodologies, though running contrary to Congress’s intent, have served to undermine the enforcement of the antitrust laws. This is not to say there is no role for economists. Economists can engage in essential fact gathering activities or provide scholarly perspective on empirical data that shows how specific business conduct can adversely affect prices, output, consumer choice, or innovation. For example, economic research has found that mergers and acquisitions habitually lead to higher prices and increased corporate profit margins – repudiating the idea that mergers are beneficial for consumers. But economists have little value to add when it comes to market definition.

Reinstituting many of the overturned per se antitrust rules all but require a change of precedent from the Supreme Court, which appears highly unlikely given the ideology of most of the current justices. However, modifying the process that enforcers use to determine relevant markets does not require overcoming such a seemingly insurmountable hurdle. Ridding antitrust litigation of the econometric process would simply require enforcers, particularly those at the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, to completely abandon the process altogether in their enforcement efforts (particularly in the merger guidelines) and instead exclusively rely on the Brown Shoe methodology. Neither the law nor the jurisprudence would need to be modified to effectuate this change—although it might be helpful, before unilaterally disarming, to first explain the new policy in the agencies’ forthcoming revision to the merger guidelines.

While some judges currently ignore or dismiss the Brown Shoe methodology, were enforcers to completely abandon the econometric process for defining markets, courts effectively would have no choice but to rely on the controlling Brown Shoe process. Unlike other aspects of antitrust law, enforcement officials can and should fully embrace the controlling law, in this case Brown Shoe, and use it readily, leaving private litigants to employ the econometric process if they so chose. Nevertheless, history indicates that courts are highly deferential to the methods used by federal enforcers—especially when explicated in the merger guidelines—and private litigants would likely follow the lead of federal enforcers in deciding which method to use to define relevant markets.

Currently, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission are redoing and updating their merger guidelines. To continue facilitating the progressive antitrust policy that began with President Biden’s administration and to start broadly de-economizing antitrust litigation, both agencies should seize the opportunity to jettison the econometric-heavy market definition tests and enshrine this change within the updated merger guidelines. Enforcers should instead exclusively rely on the sensible, practical, and fair approach the Supreme Court developed in Brown Shoe.

—

Daniel A. Hanley is a Senior Legal Analyst at the Open Markets Institute. You can follow him on Mastodon @danielhanley@mastodon.social or on Twitter @danielahanley.

From its unquestioned bailout of the venture capitalists that ultimately crashed Silicon Valley Bank, to the funneling of public dollars to corporations that shamelessly bribe public officials, the Biden Administration is developing a track record of empathizing with monopolists to whom empathy is utterly unwarranted. It’s not too late to change course.

In January, Congressional Democrats urged Biden’s Secretary of Agriculture, Tom Vilsack, to bar JBS, a food processing company, from U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) contracts following revelations that JBS’s parent company pleaded guilty to charges of bribing Brazilian officials. For its crimes, JBS was made to pay the U.S. federal government a $256 million fine for its parent’s illicit bribery scheme. But Congressional Democrats understand that this supposed justice is undercut by the millions of dollars that JBS makes off the federal government every year in contracts. Since fiscal year 2019 alone, for example, more than $283 million in American public dollars has been ushered into JBS’s coffers. That amounts to nearly $30 million more than JBS’s fine. Democratic lawmakers, understandably, found this disparity to be reprehensible, prompting their outreach to Vilsack.

JBS has for years received millions of taxpayer dollars in bailout funds and contract awards. Those funds, from our tax dollars, have helped JBS become the largest meat producer in the world and the second largest global food company.

These huge public payouts have then been wielded by JBS (and other contractors like it) to monopolize USDA’s contracting system, creating a toxic cycle of dependency that cements contractors’ dominance in their given market. It is this dependency that led Vilsack, in a letter to Congress published by Politico, to declare that barring JBS “could hurt taxpayers because the company has so few competitors,” and that as a result USDA would continue to accept JBS bids in its contracting services.

Per The American Prospect, Vilsack himself is also unlikely to implement strict contractor ethic standards, given that he’s a “henchman of the very biggest agribusiness giants,” whose chief of staff went on to become a lobbyist at the very corporation in question. The impetus, therefore, must come from elsewhere.

There are many basic ethics reforms that could address these issues, like closing the revolving door between contractors and government agencies, preventing government awards from being used for stock buybacks and union busting, and enforcing strict standards of corporate eligibility for participation in contracting bids when other parts of the government sue for violations of federal law.

Such shifts in federal contracting rules would not only protect the public from corporate abuses, but would also advance the federal government’s financial interest.

Monopolists Dominate The Contracting Market

Alas, the government’s kids-glove treatment of JBS is far from novel. Across the federal landscape, agencies continue to contract with corporations found guilty of wrongdoing simply because those same companies have monopoly power in their given fields.

According to our research, in fiscal year 2022, the federal government gave over $48 billion in public funds to contractors that faced antitrust actions from the Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2021 or 2022. Federal agencies forked over an additional $48.6 billion of taxpayer money in fiscal year 2022 via contracts to firms that faced similar action or inquiry from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) over monopoly behavior during that same period. All told, that’s just shy of $100 billion dollars that federal agencies have rewarded to corporations that were actively facing—or recently subject to—enforcement activity from other parts of the government for harmful (or illegal) monopoly conduct during 2022 alone.

To look at just the Pentagon, for example, one-third of Pentagon contracts since 2001 have been awarded to five hyper-consolidated companies: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon and Northrop Grumman. This lack of competition has “driv[en] up costs for the American taxpayer, degrad[ed federal] accountability infrastructures, and otherwise creat[ed] ‘Walmarts of War’” that hold hostage actual national security in favor of privatized profits. As the Revolving Door Project has explained, “the current [monopolistic] system also promotes the iniquitous pursuit of massive gains through ‘questionable or corrupt business practices that amount to waste, fraud, abuse, price-gouging [and] profiteering.’”

Monopolies and their prone-to-labor-abuse corporate models also hurt workers in the short term, hurt the taxpayer in the long-term, and have been found to deliver lower quality services in fulfillment of contracted work.

Last year, corporate profit margins in the United States reached their peak since 1950, as corporations padded their profits by raising prices under the pretext of rising costs, while actually fueling inflation. Meanwhile, American families suffered from runaway (and cruelly unnecessary) cost-of-living increases that have left more and more folks facing crises like homelessness and food insecurity.

While the corporate conniving fueling crippling inflation is occurring across economic sectors, it tends to be even more pronounced in highly concentrated industries with monopoly pricing power over crucial goods and services.

Monopolies are manifestly bad for consumers and they’re also bad for workers. Market consolidation leads to depressed household income and wage decreases; indeed, monopolies cost workers approximately 15-25 percent of their wages while charging the public more for less.

The Federal Government Should Be a Champion of Its Own Laws

Despite the selling power of contractors, the federal government wields significant buying power over contracted firms, as the government is the single biggest purchaser of goods and services in the world. The federal government oversees and distributes hundreds of billions of dollars to contractors each year, reaching nearly $700 billion in 2020 and $637 billion in 2021.

The sheer purchasing power of the federal government is unparalleled, leaving it with significant authority to implement and to enforce strict ethics standards for contractors. Despite this power, the government continues to casually fund JBS and other such companies’ grossly inflated profits (that hurt American consumers and families) and turned a blind eye to unlawful abuses of child labor and other workers, systemic underpayments of family farmers and ranchers, egregious food safety violations, and environmental crimes galore. Public money should not fuel the historic profit margins of corporations while those corporations hurt the public.

USDA and other large contracting agencies should be champions of the public good. They should reward contractors who do good work, and they should hold contractors accountable—and indeed stop fueling their government-sponsored bottom lines—when contractors violate federal law.

Instituting basic ethics in contracting is well within the executive branch authority and requires no action from Congress. From reevaluating what requires contractors in the first place to refusing to fund union-busting activities to refusing to promote monopolists, the contracting apparatus is fully within the purview of President Biden and his officers.

To address this crisis of competition and consolidation in contracting, this administration should bolster its existing executive order on competition by requiring executive agencies to provide a public report on the degree of competition (or lack thereof) that exists within their contracting apparatus. Biden could expand the purview of existing “advocates for competition,” to include identifying problems in federal procurement due to concentrated markets and charge. These officials could then be directed to collaborate proactively with the FTC and DOJ to actually and actively protect competition for their agency—a truly whole of government approach to competition.

Through instituting basic ethics and eligibility standards, federal agencies could foster actual competition in government contracting markets. Diversifying the deliverers of goods and services would yield greater accountability and good stewardship of public monies.

Toni Aguilar Rosenthal is a Researcher with the Revolving Door Project.

From online banking to e-commerce, advances in technology have given consumers in the digital age new products and services. But the rise of the digital economy has been accompanied by the emergence of digital robber barons. Just as social media companies entrenched their dominance by making it hard for users to port their own content and connections to rival platforms, big banks restricted users’ access to their own financial data to cement their monopoly power.

Data portability is the idea that users should be free to move their data to rival platforms. Before number portability was mandated by Congress in the 1996 Telecom Act and implemented by the FCC in 2003, cellphone customers faced high switching costs—imagine the hassle of informing your friends and family of your number—which limited churn and kept cellphone prices artificially inflated. Now big banks are up to the same tricks: To curb competition from newer and smaller companies, large financial institutions have restricted consumers’ data portability, by for example, making acts as basic as sharing personal financial data or transferring their own funds with a new institution a hassle.

Fortunately, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is initiating rulemaking that would facilitate enhanced consumer access to their financial data. Through a provision of the Dodd-Frank Act known as Section 1033, the agency can help take big banks to task and give emerging financial service providers a fair shot to compete.

Like other corporate giants that have faced regulatory scrutiny, big banks aren’t going down without a fight. Bank Policy Institute (BPI), a lobbying group whose membership includes Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase, argued in a recent comment letter that strong Section 1033 rulemaking would fuel the rise of Big Tech in the financial industry. BPI’s angle is obvious here: CFPB director Rohit Chopra is a noted supporter of regulating Big Tech, and has scrutinized the tech giants’ encroachment into the payments sector while in office.

But BPI’s spin conveniently ignores that Big Tech has been pushing into the financial services industry largely in collaboration with—and not to compete against—big financial institutions. From Goldman Sachs’ partnership with the Apple Card to TikTok’s recently exposed collaboration with JPMorgan Chase, the giants of the financial and tech industries have a vested interest in shoring up their respective monopoly positions. That BPI member JPMorgan Chase is so eager to collaborate with TikTok, a Chinese-based company drawing increasingly intense bipartisan scrutiny and even calls for its ban in the United States, is just the latest and most galling example of these developments.

Contrary to the bank lobby’s self-serving narrative, strong Section 1033 rulemaking stands to foster innovation by giving emerging companies a fair shot to compete against entrenched incumbents in both industries. Indeed, Section 1033 rulemaking will help level the playing field by giving small players and new entrants the same right to access data that Big Tech can already get its hands on quite easily.

This reality explains why consumer and competition advocates have long argued that strong Section 1033 rulemaking will help encourage competition in the financial services industry. In a 2021 comment before the CFPB, a coalition of consumer organizations led by the National Consumer Law Center argued that “Improved access to consumer-authorized data can benefit competition, which will benefit consumers.” Monopoly power comes at a grave expense to innovation, and at a time when consumers are increasingly interested in alternative relationships, this rulemaking will be a boon to the broader economy and consumer choice.

In the absence of strong Section 1033 rulemaking, access to financial services data risks being decided primarily through backroom dealmaking. It goes without saying that these informal arrangements stand to benefit mega-corporations like Google or Apple, not small players. After all, Google executives will never have a problem getting a meeting with Jamie Dimon, nor will TikTok leadership or the likes of Elon Musk. But emerging players and innovative startups are unlikely to have such opportunities, meaning that a lack of rulemaking will only entrench Big Banks’ gatekeeper status.

It would be a mistake to dismiss these concerns as merely hypothetical. As one recent example, big banks like Chase are fearful that direct account-to-account payment options will cut into their ability to profit off credit card transactions. In response, Chase is using its dominant position to steer consumers away from paying vendors directly from their own bank account. Without strong regulatory intervention, mega-corporations in tech and finance will continue to inhibit the growth of promising new ventures.

Shortly after becoming CFPB director, Chopra noted that “Big Tech companies are eagerly expanding their empires to gain greater control and insight into our spending habits.” He is correct. With the agency finally initiating rulemaking on Section 1033 more than a decade after Dodd-Frank passed into law, Chopra must reject the bank lobby’s bad faith efforts to water down the rules. The CFPB should empower consumers to fully control their personal financial data in the interest of cultivating a fair and truly competitive financial services industry.

Morgan Harper is Director of Policy and Advocacy at the American Economic Liberties Project.

Four high-profile American freight rail derailments in four weeks — three of which involved rail cars carrying hazardous materials, with multiple chemical spills and fires — sounds like a lot. In fact, trains go off the rails in America’s railroad network about 20 times a week on average, so there have probably been dozens in February aside from the ones that made the news.

Unfortunately, America’s rail workers are all too familiar with the consequences of how the railroad industry has been operated over the past 30 years. Precision scheduled railroading (PSR) has made the difference. PSR is a business model focused on reducing overhead costs and generating returns for shareholders. Similar to many other business models driven by financialization, it’s effectively a scheme by giant railroad operators to cut staff and backup resources, push the remaining equipment and personnel to the breaking point, and funnel as much of the cash as possible to Wall Street. And by increasing market concentration even further, the recently approved rail merger between Canadian Pacific (CP) and Kansas City Southern (KCS) promises to make the situation even more dire — for railroad workers, for the communities our rail lines pass through, and for the American economy.

After half a century of consolidation, America now has only seven Class I railroads, which own virtually all the long-distance track and operate almost all the freight traffic. Four of them alone control 83 percent of U.S. rail freight. And if the pending $30 billion CP-KCS merger is approved by the U.S. government’s Surface Transportation Board, the Big Seven will become only six.

In a January letter to the Surface Transportation Board, the U.S. Justice Department expressed “serious concerns about increasing consolidation” in the freight railroad industry that would result from the CP-KCS merger. In light of “the recent supply chain disruptions that have wreaked havoc on American consumers and businesses,” DOJ noted that the new combined railroad could deny commercial customers access to cost-effective and time-efficient routings, bar other railroads from interconnecting or raise their costs, and make anti-competitive coordination among railroads easier.

But the competitive risks of the merger are only part of the problem. The pursuit of profits through concentrated market power has led the large railroads to prioritize their shareholders, paying out more in buybacks and dividends (almost $200 billion) in the past dozen years than they spent on infrastructure improvements. The cash underinvestment in working conditions and safety has been paralleled by operational disinvestment, notably the shift to PSR.

Under PSR, to squeeze more money out of their railroads, these big companies have cut service to the bone while raising prices — at great cost to everyone but themselves. PSR forces workers into extended runs, on tight timetables, on longer and heavier trains. If the railroads got their way, those massive trains would be operated by a single crew member, rather than the current two. And that has led directly to the perilous state of the railroad freight network today — to conditions in which workers say trains are “more dangerous and harder to handle.”

Employee headcount across the rail freight industry has been cut by 28% due to PSR, according to a report from the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office. Freight customers say service under PSR is less reliable, and that’s because employees and equipment are being pushed to their physical limits, with no room in the system for mechanical failure, employee time off, or error of any kind. In the words of transportation consultant Karl Ziebarth, when something goes wrong, like a mechanical failure, “you can all of a sudden have a very expensive derailment.”

At the same time, the tight schedules and the length of trains inevitably means that following safety protocols may be impossible. As a Norfolk Southern employee put it, under PSR “the workers are exhausted, times for car inspections have been drastically cut, and there are no regulations on the size of these trains.” Jared Cassity, who works for a railroad union, says that railcar inspections often must be completed in under 60 seconds, not nearly enough time to identify and address problems.

The direct cause of February’s derailments are still under investigation. Regardless of the ultimate cause, it’s unlikely it could have been flagged in under a minute. But there’s no question that the dangers multiply as the length of trains, the weight of their cars, and the complexity of their cargoes increase. Average train length on the U.S. freight network has increased by 25% in ten years. The Norfolk Southern train had 150 cars and weighed 18,000 tons. During the incident, around 50 cars derailed. About 20 of those cars were likely carrying dangerous materials, including 14 carrying vinyl sulfide, all of which were on or near fire. (For reference, inhaling vinyl sulfide can be toxic.) A Norfolk Southern employee told CBS News that the train’s length had led to at least one breakdown in the days before the derailment, and said that, had the train not been so unusually large, “it’s very likely the effects of the derailment would have been mitigated.”

In the wake of the recent derailments, many have called for tighter government safety regulation. And it’s true that the Trump administration, bowing to Big Seven rail lobbyists, repealed a 2015 safety regulation that required electronic braking — similar to ABS on a car — to be installed on trains carrying certain types of hazardous cargo. Steven Ditmeyer, a former senior official at the FRA, thinks that this enhanced braking system, had it been installed, would have mitigated most of the catastrophic effects of the Norfolk Southern derailment.

It’s certainly worth questioning why Pete Buttigieg’s Department of Transportation did not move to revisit the rule in the past two years. While reversing the deregulatory carnage of the Trump administration takes (a lot of) time, starting that rule writing process as early as possible is of paramount importance: Buttigieg is up against the clock because of the 2024 election and will be hard pressed to implement all the necessary safety measures before the next inauguration. Also, while Buttigieg asking Congress for more authority to levy fines and punish corporate misconduct is a positive step, it remains concerning that he is not using the full extent of his existing powers.

But, while more stringent regulation is certainly warranted, regulations and enforcement merely exist to align incentives – because, ultimately, safe conditions depend on what management decides to do. In their pursuit of PSR, safety is exactly what the Big Seven railroads aren’t providing. In their Environmental Impact Statement, the Surface Transportation Board found that the CP-KCS merger would increase hazardous cargo transportation along 141 of the 178 affected rail segments, totaling 5,800 miles of track in 16 states. The Board found that the merger, outside of organic growth, would lead to nearly 2 million new hazardous train cars moving across the country a year, a staggering sum given the fallout of just 11 derailed hazmat cars in the East Palestine accident. And as PSR results in ever-longer and ever-heavier trains running on tight schedules, those increased hazardous cargoes are all at increased risk of derailment.

More industry concentration makes effective regulation harder. As firms increase in size, they gain more and more of a resource advantage over their regulators. One behemoth corporation can often hire more lawyers and cultivate more relationships with lawmakers in order to obfuscate enforcement measures than multiple smaller ones could. Even when efficiency gains may be real (far less frequently than claimed), the true consequence is not lower prices, but more corporate influence peddling and stock buybacks (which the railroads are infamous for).

Since 1980, the United States has gone from thirty-three Class I railroads down to only seven. As concentration increases, PSR is pursued ever more zealously; the entire point of mergers is to increase economies of scale. In practice that means investing even less money back into workers, equipment maintenance, and safety. If the companies didn’t think they could further decrease marginal operating costs, they wouldn’t want the merger. The CP and KCS merger is particularly dangerous because it will result in the only railroad with lines stretching from Canada to Mexico, which gives it a stranglehold on freight between the two countries. That further reduces incentives to maintain equipment and have adequate staff. If there’s no one else who can cater to the market, they can get away with the bare minimum. That translates to worse safety situations, higher prices, worse services, and worse working conditions.

To preserve economic competition, protect railroad workers, and safeguard the tens of millions of Americans living alongside our 140,000 miles of track, we need to halt the decline in safety and service standards that the freight railroads’ embrace of precision scheduled railroading has led to. At a minimum, the Surface Transportation Board needs to decline to approve the merger between Canadian Pacific and Kansas City Southern — and then we need the FRA, and Congress, to put into place stricter safety and operating regulations.

Dylan Gyauch-Lewis is a researcher at the Revolving Door Project.

Cartels run on collusion like a rocket runs on fuel. Therefore, if we can destroy the infrastructure that enables collusion, we can greatly deconcentrate markets. This begs the question: what exactly is that infrastructure?

For a cartel to collude, it needs to have channels of communication among its constituents. For example, OPEC routinely holds meetings. Many publicly traded companies often preview pricing in earnings calls, potentially facilitating collusion. These types of channels are the infrastructure of collusion. Without infrastructure to enable it, collusion becomes more difficult. Of course, the more concentrated the market, the less infrastructure is needed for collusion. Instead, in very concentrated markets, even some inflation in inputs is enough of an excuse for parallel and disproportionate markups in prices.

If we analogize a cartel to a many-legged spider, then consumers and workers are flies, and communication channels are the webbing on which consumers and workers are sacrificed for the nourishment of that spider. One explicit example of this phenomenon is the elite college cartel; scandalously, this cartel is a spider with a very strong web. This article examines a part of the webbing that enables sordid collusion among elite schools. This article then generalizes the lessons we can learn to markets beyond education.

As you might already know, the elite college cartel has been exposed periodically in lawsuits. For example, there was the famous Ivy Overlap case of the 1990s where the DOJ accused the Ivy League and MIT of colluding on financial aid offers. Then there was the 568 class-action lawsuit of 2022 which accused an even broader cartel of elite colleges of colluding on financial aid. Most recently, merely days ago, there was another class-action lawsuit that accused the Ivy League of suppressing financial-aid for college athletes. Even beyond the lawsuits that have already been filed, there are all sorts of anticompetitive practices that have gone unchallenged. For example, in my upcoming book The College Cartel, I allege a hub-and-spoke cartel that creates an artificial scarcity of new seats at elite colleges. Yet the question remains: how do these collusive schemes get conceived?

It’s a hard question to answer. So, let’s start with a related but different question: how does a collusive scheme get aborted prior to deployment? In theory, a firm’s governance board is supposed to step in to check any corporate misconduct and criminality. Boards of directors are supposed to set the management team straight. But what happens when the governance board is asleep at the wheel? In these instances, the check against corruption and collusion disappears.

This key insight about the abortive power of governance boards might have been why Congress sought to legislate board makeup in the Clayton Act, specifically by prohibiting the same person from serving on the boards of two competing companies. It might also be why enforcing Section 8 of the Clayton Act, the provision that bans interlocking directorates, is such a big priority for Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter. As one recent DOJ press release quoted Kanter as saying: “Enforcement of Section 8 will continue to be a focus for the division just as Congress intended…We will continue to enforce the antitrust laws when necessary to address illegal board interlocks.” Of course, Kanter has done more than issue press releases—the DOJ enforcement efforts have led to the resignations of at least thirteen directors from ten boards.

Importantly, the Clayton Act is a civil statute. Section 8 cases can be filed by anyone, and interlocking directorates are a per se violation of the Clayton Act. In other words, any of us, in the new antitrust movement, can find and file against interlocking directorates. We needn’t wait for the DOJ. This is why I’m working with a group of law students to deconcentrate the governance boards of elite colleges. In the case of the elite college cartel, persistent anticompetitive conduct has gone on for far too long. Enough is enough, and the elite college cartel needs to be purged of interlocking directorates, even if such a purge is only a partial solution.

I’m a student at Columbia Law School, and Columbia’s board of trustees has an interlock. Lu Li, chairman of the multibillion-dollar investment firm Himalaya Capital, is presently on the governance boards at both Columbia University and CalTech. By the way, remember the financial-aid price-fixing class-action I mentioned earlier? Well, both Columbia and CalTech are defendants in that litigation. Of course, it’s not just one man on two boards. Instead, interlocking directorates are a widespread problem in the elite college market. Take James S. Frank for another example. He concurrently serves on the Board of Trustees at both UChicago and Dartmouth. Again, both institutions are currently being sued for price-fixing. But my personal favorite example is none other than Carlyle founder David Rubenstein. He’s an interlocking director at three competing institutions: Mr. Rubenstein is on the governance boards at the UChicago, the Harvard Corporation, and Johns Hopkins. What’s more is that Mr. Rubenstein even used to be chairman of the board at Duke University. Coincidentally, Duke, UChicago, and Johns Hopkins are all being sued for price-fixing, and Duke has previously settled a no-poach wage-fixing case.

Lu Li, James Frank, and David Rubenstein are just a selection of the very many interlocks that exist in the elite college market. When it comes to elite colleges in America, we have a clear problem. In fairness, I’ll concede that these trustees are very accomplished and upstanding individuals. I’m not remotely arguing that they masterminded the allegedly collusive schemes for which elite colleges currently find themselves in court. Instead, my argument is more subtle. Their membership on multiple boards may have made them less likely to do anything to abort those allegedly collusive schemes precisely because they may have evaluated conduct from a more industry wide perspective. If any one of their presences made collusion even one percent more likely, then we need to act. This is why I’m working with other law students to bring these shadowy interlocks into the light. We’re going to file Section 8 civil cases.

Of course, elite colleges are merely one market where interlocks are a problem. There are many others too. Biotechnology companies seem to have particularly incestuous boards. Interlocking boards might be a reality in myriad other sectors in which you have more expertise than me. In those sectors, I’d encourage you to take similar civil action on your own, for at least three reasons.

First, interlocking directorates create a conflict of interest. When a board member sits on the board of two companies that compete in the same industry, they are likely to prioritize the interests of one company over the other. This creates a situation where one company has an unfair advantage over its competitors, and it can use this advantage to suppress competition. For example, Eric Schmidt was on the board of Apple, while Google secretly developed an Android alternative to the iPhone. This might have been an example where unfair access to information harmed one company while benefiting another. At least, Steve Jobs thought so.

Second, interlocking directorates often lead to collusion. When board members of competing companies work together, they can use their positions to coordinate their actions and manipulate the market in their favor. This can take the form of price-fixing, wage-fixing, market-sharing, bid-rigging, or other such collusive practices. For example, while then Google CEO Eric Schmidt was on the board of Apple, Google agreed not to hire certain workers from Apple, thereby suppressing wages. This eventually led to a massive settlement by Apple and Google, which compensated workers at those firms.

Third, interlocking directorates can limit innovation. When board members of competing companies work together, they may be less likely to invest in research and development that could lead to new products or services. Instead, they may focus on maintaining the status quo, which can stifle competition and limit innovation. This is especially grave in biotechnology, where less innovation means lives lost.

I encourage everyone reading this to find more interlocks and to file more cases. Change won’t come from anywhere else. The truth is that we are the ones we’ve been waiting for.

Sahaj Sharda is a first-year law student at Columbia Law School. He is the author of the forthcoming book The College Cartel.

Several antitrust commentators have noticed that, despite losing its challenge to block Meta from acquiring the leading maker of VR dedicated fitness apps, the FTC secured a victory for antitrust agencies in the sense that the opinion could rehabilitate the theory of potential competition in blocking future mergers. In full disclosure, I was the FTC’s economist in that challenge, so I won’t comment on the opinion, other than to note that (1) Steve Salop has opined that the court applied an excessive evidentiary burden in assessing Meta’s de novo entry absent the merger, and (2) Herb Hovenkamp has written that “the court made a detailed analysis of all the ways that Meta might have entered on its own, discounting all uncertainties in favor of the defendant.”

To review the bidding, potential competition is the concept that even if two companies are not currently direct competitors, there is a chance that the acquirer would enter the market occupied by the target absent the merger (or vice versa). If the acquirer would have entered with certainty, then permitting the merger harms competition by reducing the number of competitors by one, at least in expectation. Even if acquirer would have entered with some probability less than 100 percent, the mere threat of entry might impose a substantial check on the target’s price-setting power. And in a highly concentrated market, such a reduction in potential competition could lead to substantial competitive effects, including increasing the risk of coordinated pricing. Using pricing data for the merger of USAir and Piedmont, John Kwoka and Evgenia Shumilkina (2010) estimated that prices rose by five to six percent on routes that one carrier served and the other was a potential entrant.

A new tool in the agencies’ toolkit?

Now you won’t find the phrase “potential competition” in the DOJ’s challenge of JetBlue’s acquisition of Spirit. And most press reporting on the case has focused on the loss of actual competition, which would occur wherever JetBlue and Spirit have overlapping routes (150 routes according to the complaint at paragraph 31). Indeed, much has been made of the overlapping routes, such as those connecting Miami/Ft. Lauderdale and Aguadilla (Puerto Rico), where JetBlue and Spirit are on the only carriers providing nonstop service—that is, the merger is a merger to monopoly on those routes.

But the concept of potential competition is lurking in the background of DOJ’s complaint. Consider that paragraph 71 defines one set of relevant markets as “origin-and-destination pairs that JetBlue does not serve but where Spirit currently offers nonstop service or planned to enter with nonstop service as an independent.” In paragraph 34, the complaint asserts the merger would harm competition in “routes where Spirit has plans to start competing with JetBlue in the near future, and vice versa.” And the complaint notes at paragraph 6 that “over the next five years Spirit plans to add nonstop service to several routes JetBlue flies today.” These passages suggest that the DOJ plans to mount an attack on the potential competition hill. Presumably, the DOJ has acquired evidence of JetBlue’s and Spirit’s expansion plans that were hatched prior to the proposed merger. Eliminating a carrier that could expand into new markets is a loss in potential competition.

That potential competition theories are even mentioned in the DOJ’s complaint is noteworthy because prior DOJ merger cases haven’t spent much time there. And I’m not aware of consent decrees addressing the loss in potential competition. Indeed, in the go-go days of non-enforcement from Reagan to Obama, many decrees did not even care about actual overlap in city pairs when there were alleged out-of-market efficiencies.

A feckless remedy for harms to potential competition

Merging parties are quick to offer a remedy that purportedly allays harms from a loss of actual competition—namely, divestitures. In this instant merger, JetBlue has offered to spinoff Spirit’s landing slots in New York, Boston, and Fort Lauderdale. The problem with landing-slot divestitures, as DOJ’s Doha Mekki pointed out in a press conference this week, is that they don’t guarantee a replacement of lost competition on a particular route. In other words, a third party could acquire the landing slot but elect not to serve the formerly overlapping route. And as Darren Bush explained on the latest episode of The Slingshot (minute 58), divestitures of landing slots often go to third parties (approved by the merging firms) that are not capable of replacing the lost competition; a successful airline requires a network of routes to achieve the requisite economies of scope, not just a handful of landing slots.

In contrast, there is no amount of divestiture that can address harms from the loss of potential competition. If JetBlue was reasonable capable of entering a market served by Spirit, the merger will prevent that from happening. If there’s any doubt about its capability to enter new markets, JetBlue entered the Boston-Atlanta route as recently as 2017. And while Spirit allegedly planned to invade certain JetBlue markets, we can’t know which markets would have been invaded. For these reasons, the theory of harm relating to potential competition can be more potent than one based on loss to actual competition, as divestitures are not a cure.

The merging parties might argue that entry by other carriers into the affected city pairs is as easy as pointing the nose of the plane. But airlines fear retaliation from other carriers, so that’s not likely. And the industry has a history of crushing competitors that try to sneak in under the radar and build presence in city pairs, including via predatory pricing and other capacity shenanigans.

Alas, there is no mention of merger-related worker harms in the DOJ’s complaint, despite the history from prior mergers, such as the combination of US Airways and American West, which took ten years to integrate the union seniority list and faced serious problems protecting the workforce. Divestitures wouldn’t alleviate worker harms either.

Assisting the factfinder on entry probability in the absence of the merger

The assessment of a firm’s likelihood of entry absent a merger is tricky, however, particularly for folks who don’t spend a lot of time thinking about probabilities, let alone conditional probabilities. Let me try this analogy on you: A burglar has learned that you have something very expensive in your basement. Perhaps jewelry, or a collection of rare wines or baseball cards. The burglar is intent on taking your prized possession. Now imagine he tries entering your home by the front door, but the door is bolted. Does he give up? Not if he’s committed to taking what’s yours. Indeed, he will likely case the entire property until he finds an unsecured entry path. This means the probability of entering through say a side window conditional on not being able to enter through any other means is very high.

Consider a scenario where you’ve left the front door open when you went for a dog walk, the burglar tries the front door, and given your carelessness, he walks right in. And here’s the second probability lesson: That the burglar entered the front door says nothing about the likelihood of his entering the back door or window in a world where the front door was bolted shut! The reason is because the two entry pathways are mutually exclusive—once the burglar enters the front door, he will naturally abandon the other pathways. By the same logic, courts should attach zero weight to a defendant having abandoned de novo entry plans after having decided to enter through acquisition.

Let’s hope the factfinder keeps this lesson in mind when evaluating the record evidence of JetBlue’s and Spirit’s entry plans. When assessing the likelihood of de novo entry absent the merger, one must ignore any entry-related evidence after the merger has been hatched, as the merging parties will naturally abandon any plans to invade the other’s markets. There’s a ton of airline consumers depending on the court getting to the right answer.

I love eggs. I really do. There was a year in law school where I religiously made and ate an egg sandwich for breakfast every day. To this day, I believe an egg fried in olive oil until the yolks are jammy and the edges are crispy is a perfect food.

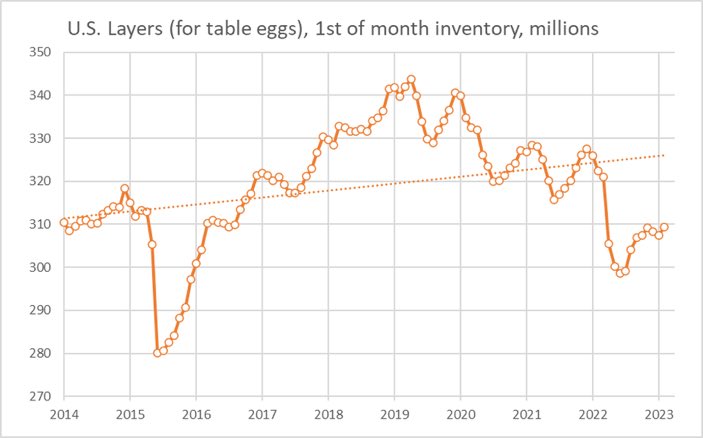

Since last year, however, my egg-loving style has been cramped. As everyone knows, the price of eggs at the grocery store more than doubled in 2022, increasing from $1.78 a dozen in December 2021 to over $4.25 in December 2022. This 138-percent increase in egg prices far outstripped the 12-percent increase Americans saw in grocery prices generally over the same period. And some Americans have had it much worse, as average egg prices reached well over $6 a dozen in states ranging from Alabama to California and Florida to Nevada.

What’s behind the skyrocketing retail price of the incredible edible egg? Well, for one thing, the skyrocketing wholesale price of that egg. Between January 2022 and December 2022, wholesale egg prices went from 144 cents for a dozen Grade-A large eggs to 503 cents a dozen. This was the highest price ever recorded for wholesale eggs. Over the entire year, wholesale egg prices averaged 282.4 cents per dozen in 2022. When we consider that average retail egg prices for the same year were only about 3 cents higher at 285.7 cents per dozen, it becomes clear that the primary contributor to rising egg prices at the grocery store has been the dramatic increase in the wholesale prices charged by egg producers.

If this gives you hope that relief might be around the corner because you’ve heard something about a recent “collapse” in wholesale egg prices, sadly your hope would be misplaced. Despite this much-ballyhooed collapse, the average wholesale egg price has simply gone from 4-to-5 times what it was in January of last year to 2-to-3 times that number. If that weren’t enough, prices are expected to spike again when egg demand picks up in the run-up to Easter. Ultimately, the USDA is projecting that the average wholesale egg price in 2023 will be 207 cents a dozen—or only about 25% lower than the average price for 2022. So much for a collapse.

Are you wondering who sets these wholesale prices? Why, an oligopoly, of course. The production of eggs in America is dominated by a handful of companies led by Cal-Maine Foods. With nearly 47 million egg-laying hens, Cal-Maine controls approximately 20% of the national egg supply and dwarfs its nearest competitor. The leading firms in the industry have a history of engaging in “cartelistic conspiracies” to limit production, split markets, and increase prices for consumers. In fact, a jury found such a conspiracy existed as recently as 2018, and a wide-ranging lawsuit was brought just a couple of years ago accusing several of the largest egg producers (including Cal-Maine) of colluding to increase prices during the COVID-19 pandemic.