Congressional Democrats managed to pass a few crucial measures during December’s lame duck session. One tiny fraction of the omnibus bill to fund the government was the Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act, a measure for which anti-monopoly advocates have long been pushing.

The Act reforms the Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) filing fee structure, the program through which the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ) collect fees from corporations seeking to merge and gain federal approval. The HSR program takes significant resources to administer, and the number of companies seeking to merge has increased in recent years — between 2020 and 2021, filing more than doubled from 1,637 to 3,644, but the fee system had not been updated to account for increased burden upon the antitrust enforcers. Due to the Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act increasing the cap on fees, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the new fees will result in $325 million in each of the first five years, with the two antitrust agencies splitting the fees and receiving $162.5 million each per year.

Congress appropriated $430 million for the FTC and $225 million for the DOJ Antitrust Division for FY2023. These budgets represent only a 22.5% and 11.9% increase from FY2022, respectively, and fall well short of the agencies’ respective requests of $490 million and $273 million. Since 2010, when adjusted for inflation, the FTC has received only a $40 million increase and the Antitrust Division a measly $7 million extra, despite processing more than double the number of HSR transactions in 2022 that they did in 2010. The agencies didn’t request more funding because they’re greedy; they need more funding to carry out their enormous missions, and Congress should support the missions.

The Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act, while an important reform, only increases what share of the FTC and DOJ Antitrust budget comes from HSR fees, and does not increase the overall budget independent of congressional funding. The recent flood of mergers (and higher valuations of those mergers) necessitates additional staff and resources at the agencies to properly review each transaction. Without more investment by Congress, the FTC and DOJ will remain pitifully short-staffed and under-resourced relative to the thousands of mergers and acquisitions that take place each year.

The perpetual underfunding of antitrust regulation has been known for years. As anti-monopoly researcher Matt Stoller pointed out, “spending on antitrust today is about a third what it was throughout most of the 20th century, and with a much bigger economy today. To get back to the level of antitrust enforcement we had in 1941 would require increasing the budgets of the agencies by ten times.”

And beyond the DOJ Antitrust and FTC’s edict to enforce competition, the FTC has another underfunded but crucial mission: consumer protection.

The FTC’s Mission To Protect Consumers Is Just As Important As Protecting Competition

In 2022, the headlines were filled with stories of corporate misdeeds, oftentimes involving deceit of customers. The FTC has a legal mandate and enforcement power to crack down on many such businesses. Through Section 5 of the FTC Act, the FTC can take legal action against companies that engage in “unfair or deceptive acts.”

The FTC has two options for enforcement under Section 5 — administrative and judicial. Administrative enforcement happens after a problem has already arisen. It involves a proceeding in front of an administrative law judge, who issues a cease and desist order if they find a given practice illegal under Section 5. It is then up to the FTC to determine whether the illegal practices warrant additional penalties, mainly through consumer redress or civil fines. Judicial enforcement, on the other hand, is a preventive measure used by the FTC while the administrative process is still underway. For example, the FTC can use judicial enforcement to enjoin a merger that will hurt consumers while the administrative judge is still determining its legality.

One of the FTC’s “top priorities” is to protect older consumers. A 2022 FTC report found that older Americans were more likely to be victims of scams and lost more money when being scammed. The best-known of these are telemarketing scams in which fraudsters convince people to transfer money by impersonating a friend or government agent, or convincing them they’d won a prize or lottery. The fraudsters can’t carry out these schemes alone — and the FTC is cracking down.

FTC Chair Lina Khan has made good on the promise to prioritize cases that harm elderly Americans. In June 2022, the FTC filed a lawsuit against Walmart for its part in facilitating fraudulent transactions that targeted the elderly. The lawsuit alleges that Walmart’s money-transfer service routinely turned a blind eye to fraudulent transactions by not training their employees or warning consumers, thus allowing the scammers to collect the ill-gotten money. Over a five-year period, over 200,000 fraud-induced money transfers were sent to or from Walmart stores, costing consumers nearly $200 million. If the FTC is successful, Walmart will have to compensate consumers for the lost money, pay civil penalties, and be subject to a permanent injunction that forces them to end money-transfering practices that result in fraud.

While older consumers are more likely to fall victim to telemarketing scams, children are unknowingly being tricked by corporations to increase their profits. Epic Games, the video game company that owns Fortnite, was fined $520 million for numerous privacy violations and “deceptive interfaces” that resulted in users, many of whom were children, making unintended purchases.

The FTC also cracked down on so-called “dark patterns” — underhanded tactics that companies use to squeeze more money from consumers including junk fees, misleading advertising, data sharing, and making it difficult to cancel subscriptions. The agency has prosecuted LendingClub, ABCmouse, and Vizio for these dark patterns, and returned millions of dollars to consumers. The public benefits greatly from this work, both by cracking down on shady schemes and putting money back in the victim’s pockets.

Although it carries out work that clearly benefits everyday Americans, the consumer protection side of the FTC often gets less press than high-profile mergers and acquisitions. But Americans are weary of corporations deceiving them to make more money off their private information. According to a 2019 study by Pew Research, 79% of Americans are very or somewhat concerned about how companies are using their personal data. Enforcing laws we already have in place shows people how the Biden Administration can help them by reining in corporate misbehavior and putting money back in their pockets.

In FY 2022, the FTC returned a total of $459.6 million to 2.3 million consumers who lost money to illegal business practices. These are material results demonstrating to people that the government can protect them from corporate shenanigans. And yet, the budget for FY 2023 underfunded the FTC by $60 million. The FTC’s budget request included funds for an additional 148 full-time staff members specifically dedicated to consumer protection, a worthy investment for addressing more of these complaints. Without the full amount of requested funds, it’s unclear how many staffers the FTC will be able to hire, but it certainly will not be enough.

The FTC should make bold requests for adequate staffing, and the Biden Administration should be willing to elevate any resistance from Congress. And don’t just take our word on why such a fight would be good politics – Biden’s prioritizing consumer protection in his State of the Union address demonstrates that he and his team see consumer protection as a political winner.

Going After Dominant Firms Is Not Enough To Protect Consumers

As with antitrust enforcement, the FTC looks to “maximize impact” of its limited resources for enforcing data privacy by going after “dominant” and “intermediary” companies. While this makes the best of the situation, this approach means plenty of abuses are falling through the cracks formed by inadequate funding for enforcement. Compare this to how the Securities and Exchange Commission often targets well-known celebrities when they engage in petty financial fraud — these cases are relatively easy to prosecute and generate headlines that hopefully give the impression of a tough agency on the beat, but these are all ultimately efforts to make do with far too little.

The actions the FTC does take against privacy-violating corporations are isolated and have limited power to deter future misconduct. For example, in 2019, the FTC fined Facebook $5 billion for misleading users by sharing personal information to third parties without their knowledge. While the fine was the largest ever levied by the agency, Facebook was using this misleading tactic for seven years in violation of a 2012 FTC order following previous allegations of even more brazenly deceptive practices.

And it is far from clear if the Trump-era FTC would have taken enforcement action but for the horrendous press Facebook generated for their relationship with Cambridge Analytica. Reliance on high stakes and high stress journalism is not a dependable basis of law enforcement – especially as journalism declines as an industry (ironically, in large part due to abuses by social media platforms). The fact that Facebook, one of the largest companies in the world, got away with deceptive data sharing for seven years also indicates that the FTC needs more resources to go after the dominant firms in addition to ensuring that smaller companies are not engaging in similar tactics. And the $5 billion fine, while historic, was a drop in the bucket for a company that hit a $1 trillion market cap not long after.

The limited financial impact of historic fines would be true for other large corporations profiting off their customer’s information as well. As Marta Tellada of Consumer Reports pointed out, “fines alone will not reform [the] market,” and the tech giants view fines “as a cost of doing business.”

And it’s not just Facebook which collects personal information on its users — today, 73% of companies in the United States do so, from small businesses to monopolies, with many opportunities for corporate malfeasance. When a potentially unfair or deceptive business practice becomes endemic across the economy, regulators cannot meaningfully “set examples” and hope the rest of the market complies. Yes, the FTC needs new rulemaking as well as congressionally-mandated tools for protecting consumers, but ramping up capacity in the meanwhile can tangibly benefit millions of Americans. The FTC needs the resources to properly enforce the laws it is already charged with carrying out.

Andrea Beaty is Research Director at the Revolving Door Project, focusing on anti-monopoly, executive branch ethics and housing policy. KJ Boyle is a research intern with the Revolving Door Project. The Revolving Door Project scrutinizes executive branch appointees to ensure they use their office to serve the broad public interest, rather than to entrench corporate power or seek personal advancement.

An analysis of public comments submitted to the FTC

In conjunction with its proposed ban on noncompete agreements, the FTC solicited comments on from any interested parties. Submission began on January 10 and, as of Friday, January 27, 2022, approximately 5,200 comments had been submitted. Fortunately, under the eRulemaking Initiative, the US Government has broadened public access to documents, permitting bulk download of comments pertaining to regulatory materials, including the FTC proposed ban on noncompete agreements.

Bulk download permits the output of all comments to a delimited text file, allowing the various fields including dates, individual and/or corporate entity submitting the comment (where available), state (again, where available) to be analyzed. Further, the comments field, which includes submissions up to 5,000 characters in length, permits text parsing for keywords such as type of employment, hourly wages, and other phrases of interest. Most importantly, the comments field reveals the submitting entity’s stance toward the proposed rulemaking.

This article describes my ongoing analysis of these data through January 27. Updated results will be uploaded periodically through the March 20, 2023 deadline for comment submissions.

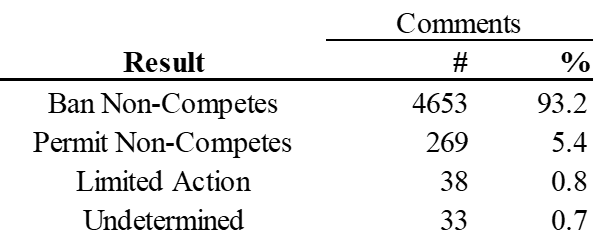

As of January 27, the results:

- demonstrate overwhelming public support for the ban on non-compete agreements. Such support is consistent across individual states, underscoring bipartisan agreement on prohibiting such restraints of trade.

- highlight the ubiquity of such agreements and their ability to constrain both lower wage and higher wage labor

- reveal that medical professionals, including physicians, represent the single most vocal group supporting the FTC’s proposed rule and advocating for a complete ban on non-compete agreements. This result exposes the flaw in attempting to cabin the scope of the rulemaking to lower-wage workers. While arguments supporting non-compete clauses may appear least defensible when encumbering lower-wage workers, the comments indicate that the negative effects are no less pronounced on those earning higher wages, such as doctors and others in the healthcare field. Further, as myriad comments observe, such constraints can have negative spillover effects, such as entrenching monopsony power, raising healthcare costs, and lowering the quality of care.

- expose the incongruity of economic theory proffered by some in defense of non-compete agreements when juxtaposed against the real-world experiences of workers who labor under such restrictions.

The overall results including comments submitted through January 27, 2023 appear in Table 1 below. Overall, approximately 93% of comments reflect support for the FTC’s proposed ban. Determination of whether the respondent supported or opposed the FTC rulemaking proceeded as follows. Of the approximately 5,200 comments received as of January 27, I reviewed approximately 3,626 by reading or skimming each comment individually. The reminder were classified as 1) supporting the ban if they contained keywords such as “depress”, “oppress”, “trap”, “archaic”, “in favor”, “eliminate”, “monopoly” or 2) opposing the ban if they contain key phrases such as “to the state”, “overreach”, “object”, “oppose”, “protect small”, “damage small”, “hurt small”, “harm small”. The latter comments were interpreted to mean that the FTC’s rulemaking would hurt small businesses or infringe upon states’ rights. Individual review of the 3600+ comments informed the determination of the keywords and phrases used.

Table 1. Results

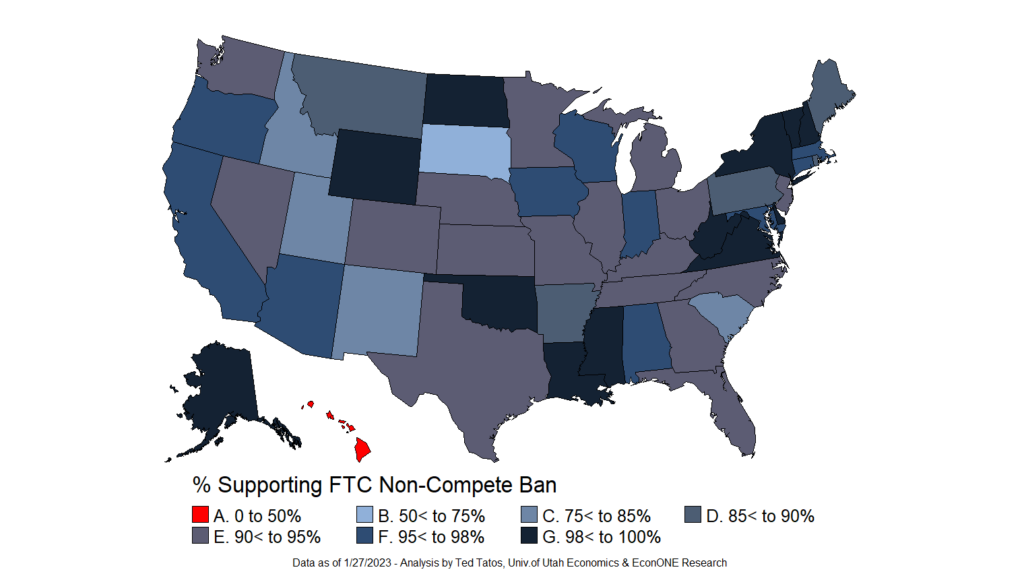

The overwhelming support for the FTC’s rulemaking banning non-compete agreements shown in Table 1 extends nationwide, with every state except Hawaii (n=2) indicating that the majority of commenters favor of the FTC’s proposed ban. Among states with at least 10 respondents, the lowest rates of approval were 78.9%, 80% and 81.8% for New Mexico, Utah, and South Carolina, respectively.

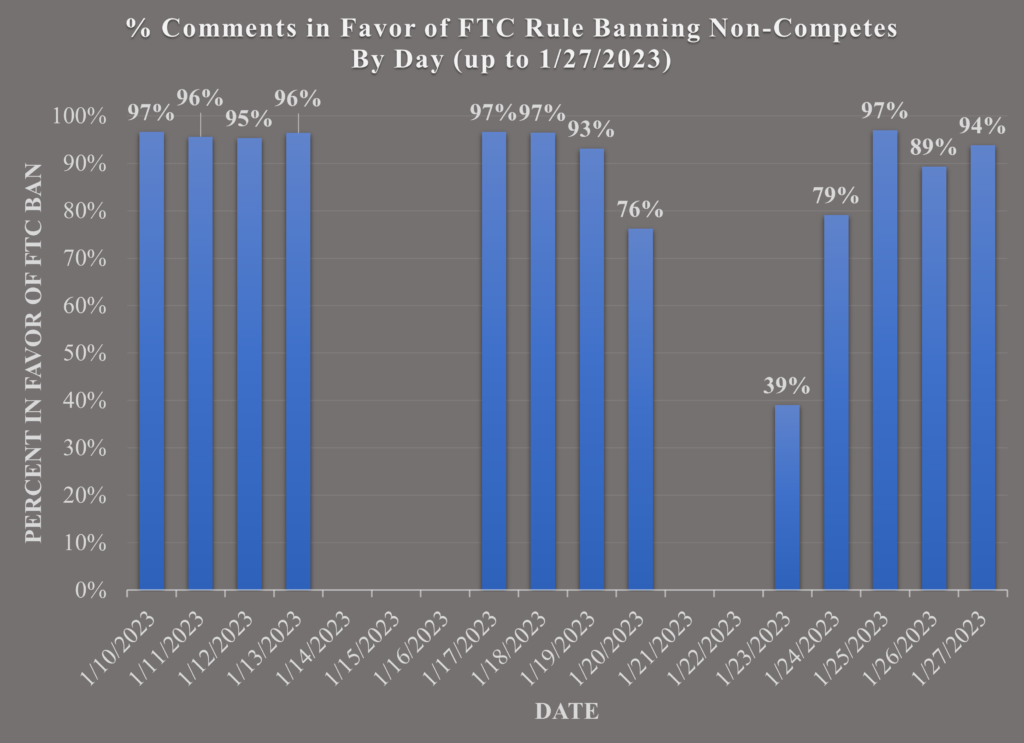

The figure below provides a daily breakdown of the percentage of comments submitted that supported the proposed ban on non-compete agreements. The results provide some evidence of coordination of responses in opposition to the FTC’s position. A substantially higher proportion of comments opposing the proposed rulemaking occurred during the 3-day period of January 20, 23 and 24 (the 21st and 22nd were weekend days so the data did not include comments on those dates), reaching a zenith on January 23.

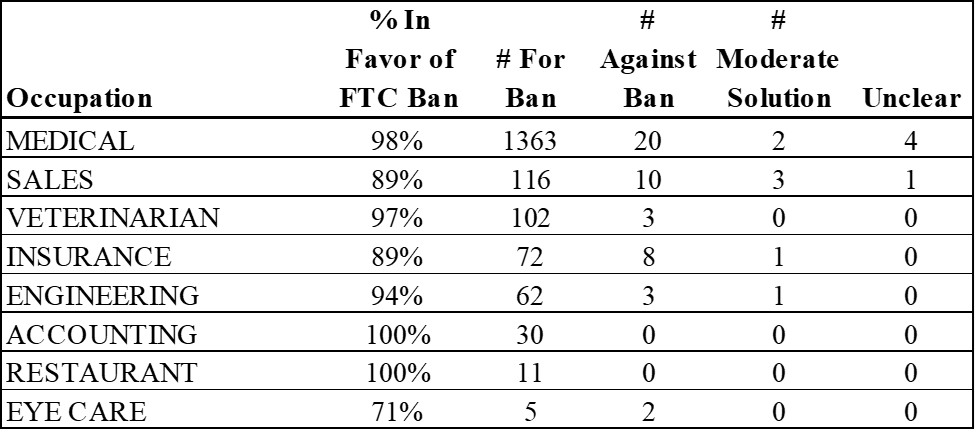

I also analyzed the extent of support for the ban on non-competes by occupation, as reflected in the comments. By far the most common occupation listed referenced work as either a “physician”, a specialty therein (e.g., cardiologist, radiologist, etc.) or a generic description of the medical field. Other noted occupations included accounting (e.g., CPA), dentist, veterinarian, engineering, spa/salon, insurance, or restaurant-related work.

The support among physicians for the ban on non-competes was nearly unanimous. Approximately 98% decried the use of non-competes, citing their harm to physician careers, their families, as well as the negative impact non-competes have on quality of care.

Support for non-competes largely originates from owners of individual practices who expressed concern that their employees may leave and “open up shop across the street” and compete with them. However, even business owners overwhelmingly support the FTC’s proposed rule. Among comments that included terms such as “small business” or “small company(ies)” approximately 68.9% of comments favored the FTC ban, a nearly identical result when evaluating comments indicating ownership of a company (69.3% in favor of the FTC ban).

Many supporters of the FTC’s planned rulemaking vehemently rejected the restraints imposed by non-compete agreements, likening them to indentured servitude, slavery, and using evocative terms such as “toxic”, “chains”, “prison”, “trap”, “bully” and “exploit”. Of the 4653 respondents who supported the FTC’s ban (93.2% of total), approximately 730 (15.7%) used at least one of these terms in their comments.

Note: Ted Tatos is an adjunct professor of economics at the University of Utah and a testifying expert with EconONE Research. This analysis of responses to FTC comments will be updated periodically until the March 20 deadline.

The Federal Trade Commission recently announced it is proposing to ban non-compete agreements between employers and workers. We are of the opinion that much of the conversation about the FTC’s proposed rule, both in terms of its substance and its ability to promulgate, are muddled between differing concepts. Our takeaway is that there is no justification for non-compete agreements once one sets aside Trade Secret protection—a matter already protected by existing law. We also argue that arguments about why the FTC should avoid challenges to its authority are overbroad: Essentially, the argument that the FTC should shy away from rulemaking because of the “major questions doctrine” and the “non-delegation doctrine” suggest that no agency should ever attempt to do anything. Moreover, the FTC has the better argument on these issues.

No Legitimate Business Justification

For present purposes, we set aside non-competes that are part of the sale of a business, as well as trade-secret provisions. We focus solely on clauses that restrict post-employment labor market activities. We refer to these contract terms as post-employment non-compete agreements or non-compete agreements. In the case of a trade secret (not protected by a non-compete agreement but a trade-secret protection clause), a business may have a protectable intellectual property interest. To bring a misappropriation of a trade-secret case, the employer must come forward and identify the trade secret, show that (a) it has competitive significance, (b) the employer took reasonable steps to protect the secret, and (c) the employee misappropriated the secret. In such cases, the claimed business justification is put to the test.

That’s not the case with post-employment non-competes. One of the authors has practiced law in Utah for more than three decades, a state that vigorously enforces non-compete agreements. In nearly every case, the central issue is: What exactly is the legitimate business interest being protected? In our experience, there is no credible business interest that justifies a non-compete agreement. While many corporate lawyers and business litigators will fight to enforce a client’s non-compete, and we have done this as well, there is rarely if ever a credible case. Ironically, the attorneys themselves never agree to their own non-compete agreements, and the American Bar Association’s Model Rule 5.6 (“Restrictions on Right to Practice”) makes non-competes among attorneys and law firms unethical. Is it the case that law firms are somehow different and have no legitimate interests to be protected like other businesses?

States that enforce non-competes usually adopt some version of the Restatement (Second) of Contracts Section 188. Under the rule, the post-employment non-compete restraint cannot be greater than needed to protect the legitimate business interest. Our main point is that there is no legitimate business interest in an employment non-compete agreement. Any effort to define the geographic scope or the duration of the restraint is pure fiction. Lawyers who draft these agreements don’t define relevant markets or estimate the time it takes to depreciate some alleged goodwill. They simply draft the broadest language they believe they may get away with either because litigation is unlikely, or the local precedent provides a good faith argument. This is because, again, there is almost never a credible business interest to be protected in the first place.

So what possible reason could a business have for preventing former employees from working where they choose, independent of trade secret issues such as secret technology or client lists? The classic answer appears in the lead Utah case where a clerk at a pharmacy through his hard work gains the trust of local patrons. The company claimed ownership in that goodwill.

How many situations are like this in today’s economy? According to a study by the Economic Policy Institute, roughly half of all businesses in the United States use non-compete agreements. It is not reasonable to believe workers at half the nations’ firms have acquired company-related customer goodwill sufficient to injure the company. American companies themselves do not seem to think so. Companies must report goodwill on their financial statements. Yet you will not find the list of their employees with non-competes reported as material sources of company goodwill. Indeed, if an employee does increase its employer’s goodwill with the public by their own efforts, why remove their bargaining power to increase their wages? The employee should be compensated for these achievements. Allowing the firm to appropriate the fruits of such efforts is the essence of “exploitation.”

One argument some businesses make is that the non-compete agreements are necessary to protect their investment in employee training. We find this argument particularly untenable. Non-compete incidence is rising among holders of professional degrees. A Ph.D. with a science background comes to a firm with significant human capital acquired over years at their own expense. The same is true of lawyers, accountants, and physicians. Often additional training occurs through professional organizations. For example, an accountant may receive training in valuation from the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, or a lawyer may learn how to take a deposition at a National Institute for Trial Advocacy seminar. There are often continuing education requirements. The internal investments by firms in training are trivial in comparison, and what little there is to protect can be protected through trade-secret contract agreements. Such training may also not be valuable to other firms and may not lead to competitive injury. This seems particularly true at the lower end of the labor market. Learning the McDonald’s process may not be particularly useful at Burger King.

Moreover, investment in training takes place without non-compete agreements. It is unlikely that firms in California train less than other states. Law firms invest heavily in training without non-competes. There is no need to give employers the equivalent of an equitable stake in an employee’s human capital to induce training. We don’t allow banks to do this with student loans, and the same public policy should prohibit non-compete agreements as an incentive for training. In both cases, student loans and training will occur without the draconian “exploitation.”

Workers Generally Do Not Negotiate for Non-Competes

Even if there were a legitimate business interest in preventing former employee labor mobility, the Restatement further avers that such an interest can be outweighed by the hardship to the worker or the public. The FTC’s Supplementary Information accompanying its Notice of Proposed Rulemaking comprehensively reviews the economic literature relevant to these two points. The weight of the evidence from the economic studies show that non-compete agreements (a) lower wages, (b) increase racial and gender wage gaps, (c) harm entry and business formation because they impede labor mobility (one can speculate what would have happened if Shockley Semiconductor had non competes with the future Fairchild and Intel founders), (d) increase medical costs, and (e) may reduce innovation.

One of the most frustrating situations for an employee who becomes a party in a non-compete agreement enforcement action is to face a judge who views a post-employment non-compete as purely a contract issue. Early Chicago School law and economics encouraged this simplified thinking. The logic is that since there is a valid contract, and the employee voluntarily chose to execute it, it should be enforced (sometimes this is called the employee choice rule). This logic would only hold under conditions of perfect competition—that is, full information on both sides, equal bargaining power, and no issue of externalities impacting markets and the public. Most judges know this kind of thinking is pure ideology simply based on their knowledge of the common law. The common law itself recognizes that perfect competition is a fiction. The contract defenses of mutual mistake and frustration of purpose are because of asymmetric information. The defenses of unconscionability, duress, and necessity result from unequal bargaining power, and of course, restraints of trade are because of externalities.

To simply enforce a non-compete because it is in a contract, a judge must put on his or her ideological blinders and ignore the real-world factual record. In our litigation experience, employees learn about the non-compete for the first time after the job negotiations are completed and it is time to sign the paperwork. This often occurs after the employee has started the job. The non-compete is often in fine print and written in legal jargon. The contract terms are often presented as a nonnegotiable firm policy. If the worker wishes to negotiate, they are placed in a position where they must risk starting a major confrontation on their first day of work. And to adequately understand their rights will result in a long work delay. Thus, even if the employee might have not agreed ex ante to the non-compete agreement, by the time of the contract (or when they get around to reading the employee handbook), they agree ex post. According to the EPI survey, the vast majority of non-compete agreements are executed without any negotiation.

Answering Commissioner Wilson’s Dissent

This brings us to FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson’s dissent. True to form, she is most concerned that a rule against employee non-competes might harm “the business justification that prompted its adoption.” Of course, she never identifies or defends that business justification, Nonetheless, she knows that there must be something to be defended, and “unelected bureaucrats” shouldn’t interfere. Interestingly, elected officials seem to differ with Commissioner Wilson. Indeed, as noted by the FTC, three states already have rendered employee non-competes unenforceable, and many other states have limited their application. There is no identifiable trend in the other direction. The FTC proposed rule advances a sound policy that will promote economic development and the interests of consumers, workers, and new business formation.

Commissioner Wilson’s jurisdictional objection is that the FTC may not have the power to promulgate a rule against non-compete clauses. This is also the point recently made by Chicago law professor Randy Picker. They both imply that if legal challenges could occur, the Commission should censor itself in advance and give up on policies that improve welfare. For them, the potential protection the rule could afford workers (and ultimately consumers) is not worth the risk of a courtroom loss. We disagree both on the philosophy and on the merits. In connection with the merits, what cannot be disputed is that Section 5 of the FTC act covers non-competes. Binding precedent allows the FTC to bring cases under Section 5 that are covered by the Sherman Act. The Sherman Act prohibits contracts in restraint of trade. A non-compete agreement is a contract, and there is no doubt that the Sherman Act was meant to apply to common law restraints of trade.

The classic example of a restraint of trade is a non-compete agreement (and is where the name “restraint of TRADE” derives). Indeed, Justice White in the Standard Oil Case, which introduced the rule of reason, traces the common law of restraints of trade from Mitchel v. Reynolds, a covenant not to compete case. Because, in our view, post-employment covenants have no legitimate procompetitive purpose, they should be considered per se illegal. This was the view of the district court in Newberger, Loeb & Co. v. Gross, 563 F. 2d 1057, 1083 (1977) (“Restraint on postemployment competition that serve no legitimate purpose at the time they are adopted would be per se invalid”).

But courts in several cases have found that non-competes can protect interests in trade secrets and customer good will. For example, Aydin Corp. v. Loral Corp, 718 F 2d 897, 900 (1983). Therefore, at present the rule of reason is the norm. In our view, these courts have made an unjustified melding of trade secrets and post-employment non-compete agreements. Although a trade secret can be a legitimate interest, it is best handled by a separate contract clause, while the post-employment non-compete agreement is without any legitimate merit. Because of this confusion, post-employment covenants are analyzed under the rule of reason, and under this standard they inevitably fail. This is because it is virtually impossible to demonstrate a market effect emanating from a single or limited number of non-compete agreements, particularly where contracts include arbitration and/or non-class action clauses. In this legal context, Section 5 of the FTC Act can play a critical role. As the Supreme Court stated in FTC v. Brown Shoe Co, Section 5 “is particularly well established with regard to trade practices which conflict with the basic policies of the Sherman and Clayton Acts even though such practices may not actually violate these laws.” 384 US 316, 321 (1966).

On the FTC’s Legal Authority

The remaining issue is whether the FTC is authorized to promulgate a rule against employment non-compete contracts. There is great back-and-forth about whether the language of 6(g) of the FTC Act allows for unfair methods of competition rulemaking. The pre-Chevron doctrine D.C. Circuit decision in Nat’l Petroleum Ref’rs Ass’n v. FTC, 482 F.2d 672 (D.C. Cir. 1973), found such rulemaking authority.

In a nod perhaps to Justice O’Connor’s FDA v. Brown & Williamson decision, Commissioner Wilson notes that the Magnusson Moss Act (establishing Sisyphean barriers to Unfair Trade Practices Rulemaking) expressly carved out unfair methods of competition rulemaking. Commissioner Wilson suggests the reason is reliance on statements by FTC Commissioners and Chairs past disclaiming such authority.

Her argument faces two logical hurdles. The first is that the plain language of the FTC Act, which implies that that the agency has such authority: “From time to time classify corporations and (except as provided in section 57a(a)(2) of this title) to make rules and regulations for the purpose of carrying out the provisions of this subchapter.” To the extent we are all textualists now, it is surprising to see conservative flight to legislative history and former FTC Commissioner statements.

The second logical hurdle is that Chevron Doctrine is dead. Chevron in essence states that where a statutory provision is ambiguous, the Agency’s interpretation shall be given deference so long as that interpretation is reasonable. There is no discussion in Commissioner Wilson’s dissent of Chevron. One can only assume she believes the FTC deserves no deference.

Those are not the only precedents that appear to be ignored. Commissioner Wilson and others argue that it is improvident for the FTC to engage in rulemaking on this issue rather than adjudication. However, the Supreme Court has spoken on this issue as well. In “Chenery II,” Justice Murphy wrote (emphasis ours):

Problems may arise in a case which the administrative agency could not reasonably foresee, problems which must be solved despite the absence of a relevant general rule. Or the agency may not have had sufficient experience with a particular problem to warrant rigidifying its tentative judgment into a hard and fast rule. Or the problem may be so specialized and varying in nature as to be impossible of capture within the boundaries of a general rule. In those situations, the agency must retain power to deal with the problems on a case-to-case basis if the administrative process is to be effective. There is thus a very definite place for the case-by-case evolution of statutory standards. And the choice made between proceeding by general rule or by individual, ad hoc litigation is one that lies primarily in the informed discretion of the administrative agency.

It is entirely possible the Court will ignore its own precedent, but the FTC should not be so quick to do so like antitrust practitioners did with Philadelphia National Bank and other pre-consumer welfare decisions. The FTC should stick to protecting the public and not give deference to the Chicago School over controlling precedent.

The Constitutional Issues

Commissioner Wilson invokes Constitutional issues in apparent eagerness to eliminate her own agency’s authority. In doing so, she assumes that in any “major questions doctrine” (MQD) challenge to the FTC’s rulemaking the Supreme Court will rule against the agency. This is not an unreasonable assumption, given the MQD appears based on Judicial Activism to hijack Congressional intent and Agency autonomy and transfer power to the Supreme Court. Quite simply, according to the Supreme Court, the doctrine suggests that

there are extraordinary cases in which the history and the breadth of the authority that [the agency] has asserted, and the economic and political significance of that assertion, provide a reason to hesitate before concluding that Congress meant to confer such authority… Under this body of law, known as the major questions doctrine, given both separation of powers principles and a practical understanding of legislative intent, the agency must point to clear congressional authorization for the authority it claims.

But are all administrative rulemaking cases a major question? Are all rulemakings “extraordinary?” Is every rulemaking that benefits society destined to end in a MQD challenge? If that’s the case, then no agency rulemaking is safe, and the argument that the FTC should not promulgate this rule should really be that no agency should promulgate any rule, despite decades of precedent to the contrary. And perhaps that is the end goal that her comments imply she would favor.

Finally, it could be the case that the Supreme Court will just end the administrative state altogether. Certainly Justice Thomas has signaled that way. The “non-Delegation doctrine,” as some would have it, would kill independent administrative agencies, and perhaps the administrative state altogether.

These issues are shared by all administrative agencies, not just the FTC. So to claim that such rulemaking might bring the downfall of the administrative state understates the argument: Any rulemaking might do so, if five justices decide to again ignore precedent to gain power to halt changes that protect the public.

Conclusion

It is telling that a notice of proposed rulemaking has created such ire. Firms rely on non-compete agreements to “unfairly exploit and coerce” workers by minimizing worker leverage, depress their wages, and protect non-existent interests. Trade Secret law already protects any relevant employer interests. But firms favor less competition in the labor market and in the output markets in which they operate.

And Commissioner Wilson is happy to help them. The Notice itself is keenly aware of the history Wilson lays out (and the administrative law she ignores). Warning an agency to do nothing because it will bring backlash by the Supreme Court is a well-established antitrust philosophy. It is one that needs to change.

Mark Glick is a professor of economics at the University of Utah. Darren Bush is a professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center. The views express here are those of the authors only, and do not represent the views of their respective institutions.

The recent debacle that saw Taylor Swift concert tickets surge as high as $22,000 has prompted the United States Senate to join antitrust authorities in reexamining the controversial merger that created Live Nation Entertainment (LNE), the corporation that mishandled ticket sales for the event. The deal, consummated in 2010, combined two already powerful firms —Ticketmaster, which dominated ticketing services for events, and Live Nation, which was the leading event promoter — into a near monopoly.

Critics predicted that LNE would abuse its market power in ways that hurt consumers, artists, and venues, and they proved to be right. Ticket prices, for example, have nearly tripled in the last two decades. In December, the company followed up its fiasco with Taylor Swift by botching ticket sales to a Mexico City concert by Bad Bunny, one of the world’s biggest pop stars, prompting calls for an investigation by Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López. Meanwhile, LNE has coerced artists and venues into using its ticket-selling services exclusively — a practice known as exclusive dealing that violates antitrust law.

Fortunately, it’s not too late for the federal regulators to remedy the mess. In addition to a lawsuit being developed by the Department of Justice (DOJ), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) can use some of its long-neglected – but recently awakened – powers to create market-wide rules targeting LNE’s use of exclusive dealing, a predatory practice that garners little attention with headlines focused on Ticketmaster’s prohibitive ticket prices and botched ticket sales.

* * *

The story of the merger that created LNE illustrates almost every mistake the government can make in preventing monopolies. When it approved the merger twelve years ago, DOJ knew that Ticketmaster was already operating as a virtual monopoly, having captured 80 percent of the primary ticketing market.

DOJ also knew that Live Nation possessed significant power in the live entertainment industry. Live Nation was the leading concert promoter, whose role involves contracting the chosen venue, handling the advertising, and managing other production services. Live Nation managed a third of major concert events in the United States, and owned 75 concert venues.

Moreover, due to its position as the nation’s leading promoter, Live Nation was well positioned to develop its own primary ticketing service and challenge Ticketmaster. Soon after entering the primary ticketing market, Live Nation became the second most dominant firm in the industry, controlling 16.5 percent of ticketing sales.

Nonetheless, the Obama administration’s DOJ approved the merger, demanding only a consent decree (formal legal jargon for a settlement) that required LNE to agree to certain minimal conditions. LNE was required, for example, to (1) divest a small division of its company, (2) not share consumer information collected from its ticketing business, and most importantly, (3) not engage in any retaliatory or unfair practices, such as exclusive dealing. LNE would soon blatantly violate all three conditions.

Consequently, consumers, entertainers, and venue operators have had to endure the full brunt of the merged firm’s monopoly power. The New York Times detailed in 2018 how “Live Nation and its operations extend into nearly every aspect of the concert world,” further expanding its dominant position by withholding access to its events if its customers did not use Ticketmaster’s ticketing service.

LNE also uses its power to take more of a cut of the proceeds and, by virtue of shutting out venues that refuse to comply with LNE’s terms, limit an artist’s access to venues, even if that venue can offer better terms to the artist. Artists themselves are put in a position in which to avoid angering fans over unaffordable ticket prices, they have to reduce their own earned income from the event to ensure stable and fair prices.

LNE’s violations of its merger settlement were so blatant that the DOJ under Trump faced enormous political pressure to amend the consent degree with harsher terms, which it did. But these proved insufficient to infusing competition into the industry and major abuses continued.

Today, in addition to the abuses already described, LNE engages in kickback agreements to share its monopoly profits with venues to promise not to take their business elsewhere. Firms failing to submit to LNE’s demands can expect explicit or implicit retaliation against them by LNE cutting them off from all its services.

The hardball tactics have worked. As one lawsuit cogently describes, LNE has locked up over 70 percent of concert venues — numbering 12,000 individual locations — across the United States to exclusively use LNE’s Ticketmaster service, satisfying the significant foreclosure requirement in exclusive dealing law (typically at least 30-40 percent). Each contract is, on average, five to seven years long and sometimes exceeds ten years, satisfying the duration requirement in exclusive dealing law.

Exclusive dealing requirements like these are a centuries-old means of forestalling competition and building monopolies among businesses that sell to other businesses. They prevent a firm from choosing among different competing suppliers, thereby tending to make dominant suppliers still stronger. As I describe in a forthcoming law review article, exclusive dealing requirements restrict the freedom of businesses to select their suppliers or customers, as well as reduce and deter competition – making them “weapons of subjugation that allow dominant corporations to exert their power to maintain their control and be able to punish dependent firms.”

The antitrust laws, such as Section 2 of the Sherman Act, Section 5 of the FTC Act, and in some cases Section 3 of the Clayton Act, broadly prohibit exclusive dealing. LNE’s conduct also clearly violates the controlling Trump-era settlement, which explicitly restricts LNE from “Condition[ing] or threaten[ing] to Condition” its services in a manner that prevents venue owners from “contracting with a company other than [LNE] for Primary Ticketing Services[.]” Indeed, a class action lawsuit initiated in 2022 makes such assertions.

Additionally, other factors such as LNE’s monopoly power and the number of venues locked in by LNE’s exclusive arrangements make antitrust litigation likely to succeed. The ticketing and venue market has extensively high barriers to entry: there are only so many venues, and so many artists that draw massive crowds to fill up venues.

Supporters of the merger could counter by pointing to the fact that concert venues need ticketing service firms to have a proven record of reliability, experience, and scale to handle significant sales volume. Yet Ticketmaster’s recent mismanagement of Taylor Swift’s and Bad Bunny’s concert tickets show that LNE by itself could not provide the necessary level of service. Maybe if LNE faced more competition, it would improve the quality of its service.

Now that millions of Taylor Swift fans have discovered the evils of monopoly, a federal lawsuit against LNE would be bound to receive lots of press attention and wide public support. Initiating a federal lawsuit would also showcase that antitrust enforcement can directly rein in corporate power, and that it can provide tangible benefits to consumers — such as lower ticket prices, higher quality handling of ticket purchases, and increased open access to resale tickets. Moreover, a lawsuit would represent an implicit admission that settlements of the kind that was supposed to restrain LNE are not an earnest policy position that restrains dominant corporations and that litigation and remedies, such as structural breakups, should be the preferred enforcement route.

Antitrust litigation, to be sure, is costly, time consuming, and, more importantly given the current construction of the federal judiciary, unpredictable. Particularly over the last 40 years, reviewing courts have shown little hesitation in rewriting the rules to favor dominant corporations. Furthermore, because significant portions of antitrust litigation are based on a defendant-friendly burden-shifting framework known as the rule of reason, successful litigation against one company does not automatically translate into successful litigation against another corporation using similar market practices. Yet in this case, even if litigation fails, an even better solution is available.

Congress endowed the FTC with broad, delegated authority to enact economy-wide rules prohibiting unfair methods of competition. The FTC can use its power to enact a rule that would prevent the use of exclusive deals by dominant firms or when exclusive arrangements restrict access to an undue percentage of the market. A July 2020 petition to the FTC, signed by over 30 scholars and advocacy organizations, including my current employer, the Open Markets Institute, supports such a rule. The FTC’s recent proposal banning non-compete agreements using this latent power, reveals that the agency can initiate a similar proposal against exclusive deals.

A rule banning monopolistic and unfair uses of exclusive arrangements, like those employed by LNE, would have many benefits. A bright-line rule would provide exceptional clarity for businesses to know when exclusive deals are allowed. A rule would also avoid the currently onerous requirements of antitrust litigation by limiting the analysis courts would engage in.

As the Supreme Court once stated, clear rules “avoid the necessity for an incredibly complicated and prolonged economic investigation into… a particular restraint… an inquiry so often wholly fruitless when undertaken.” Clear rules also limit the unduly expansive prosecutorial discretion afforded to public enforcers. The FTC should act as quickly as possible to use it full powers. In the process it will not only uphold the role of law and fair marketplace but will win the gratitude of everyone who doesn’t want to pay monopoly prices to see their favorite entertainer.

Daniel A. Hanley is a Senior Legal Analyst at the Open Markets Institute. You can follow him on Mastodon @danielhanley@mstdn.social.

Disclosure: Daniel is employed at the Open Markets Institute, which along with 36 other organizations and scholars, petitioned the FTC to use its unfair methods of competition rulemaking powers to prohibit exclusive contracts.

Over the last year, three of the four current FTC Commissioners (one seat is vacant) have indicated an interest in renewed enforcement of the Robinson-Patman Act as a potential means of policing anticompetitive conduct. The most robust support has been voiced by Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya, who delivered a speech on the subject on September 22, 2022 at a Minneapolis event titled: “Midwest Forum on Fair Markets: What the New Antimonopoly Vision Means for Main Street.” Commissioner Bedoya titled his speech “Returning to Fairness,” and through three anecdotal case studies, expressed skepticism of the prevailing paradigm that “efficiency” is (or should be) the paramount goal of the antitrust laws. As Commissioner Bedoya pointed out, none of the Congresses that enacted any of the familiar antitrust acts invoked “efficiency” as their central purpose; indeed, none of them even mentions “efficiency” as a goal. Rather, he explained, those Congresses targeted “unfairness.” He summarized his views thusly:

Certain laws that were clearly passed under what you could call a fairness mandate – laws like Robinson-Patman – directly spell out specific legal prohibitions. Congress’s intent in those laws is clear. We should enforce them.

With Commissioners Khan and Slaughter having previously expressed similar sentiments, it is not surprising that opponents of a resurgent RPA have been quick to respond. On October 11, 2022, the American Action Forum published a “primer” titled “FTC to Use Robinson-Patman Act as an Antitrust Tool to Target Large Retailers,”[1] and a week later the Cato Institute published an article titled “The Zombie Robinson‐Patman Act Doesn’t Deserve Revival.”[2]

These articles repeat a series of criticisms that will be familiar to anyone who has spent time with the Robinson-Patman Act (the “RPA”). For example, the article from the Cato Institute proclaims that “[b]y inhibiting more efficient firms from receiving wholesale discounts, the RPA therefore denied retail consumer savings in the form of lower prices,” and that “[i]f enforced again it would no doubt smother efficiencies once more, resulting in higher prices for customers.” The piece from the American Action Forum likewise expresses the concern that “expansion of the use of the RPA as an antitrust tool could have major implications for consumers,” because “[a]n RPA claim may ignore the efficiencies firms generate that come with scale,” such that “consumers will likely pay higher prices.” These criticisms echo those from former FTC Commissioner Noah Phillips, who testified to the House Judiciary Committee of the last Congress that an “unfortunate result [of the RPA] was that American consumers paid more money for groceries and household products that they use every day.”[3]

These recurrent criticisms of the RPA have echoed since the “Chicago School” of economic theory gained ascendance in the Reagan administration and have been repeated with such frequency and certainty that they have become truisms. One may then be surprised to learn that despite 40+ years of repetition, these familiar criticisms are entirely lacking in empirical support. As Commissioner Bedoya recognized, “some 86 years after its passage, there is not one empirical analysis showing that Robinson-Patman actually raised consumer prices.” Indeed, when one traces the lineage of these familiar criticisms back through the literature, he finds that the supporting citations (where citations are offered at all) are only to prior works voicing the same criticisms. And if one delves even further back, he will find that the criticisms did not originate in the work of economists at all, but in the works of laissez faire legal scholars. That is, the familiar criticisms largely originated in the writings of Judges Bork and Posner, and Professor Hovenkamp, all of whom stated the criticisms as axiomatic.[4] Perhaps now when a potential revival of the RPA is at hand, it is finally time to query whether the generally accepted condemnations of the RPA are valid to begin with.

1. Are the companies that receive discriminatory pricing “more efficient”?

One might begin with the criticism that the Act prevents suppliers from giving favorable pricing to “larger, more efficient businesses.”[5] This criticism contains two (apparently unrecognized) assumptions: (1) that “larger” businesses obtain discriminatory pricing because they are more “efficient” and (2) that the Act prohibits discounts associated with actual efficiency.

As to the first, what evidence is there that suppliers grant preferential pricing to customers based on their “efficiency”? It’s a rhetorical question; the answer is “none.” Perhaps the proponents of this criticism don’t really mean demonstrated “efficiency,” but instead use “larger” as a proxy for “more efficient.” But if that’s what they mean, why do they feel the need to cloak bigness in the garb of “efficiency”? Surely they recognize that a customer like Walmart or Amazon is able to demand preferential pricing based purely on its largeness, with no regard to its “efficiency.” This same criticism of the RPA has been leveled for more than forty years, but I have read volumes of RPA literature and caselaw, and am not aware of any empirical study showing that big businesses are more efficient than small businesses in the only metric that is relevant to the RPA—the cost to the supplier of making sales to its customers.

In the real world, we have substantial reason to doubt whether it is more efficient for a supplier to sell to big businesses than to their smaller competitors. Our firm has litigated only two RPA cases where cost information as to the favored and disfavored purchasers has been produced in discovery. In these two matters, we learned (from the defendants’ own calculations) that because of Costco and Walmart’s exacting packaging and delivery requirements, it was more costly for the supplier to supply those giants than it was to supply their independent competitors. Nevertheless, both suppliers gave Costco and Walmart better pricing merely because the behemoths demanded it. While two is admittedly a tiny sample, it is also two-out-of-two. Before we adopt economic and public policy around the assumption that big businesses should be entitled to discriminatory pricing because they are “more efficient,” we at least ought to know whether it’s true.

Moreover, the RPA includes a specific provision that protects sales to firms that are actually more efficient. Under the “cost-justification” defense, “nothing herein contained shall prevent differentials which make only due allowance for differences in the cost of manufacture, sale, or delivery resulting from the differing methods or quantities in which such commodities are to such purchasers sold or delivered.”[6] In other words, where it is actually demonstrably cheaper for a supplier to sell to Walmart or Costco than to their smaller competitors, the RPA permits a lower price offer. The Act only prohibits discounts that cannot be justified as more efficient.

The response that the cost-justification defense is “virtually impossible” to meet is unconvincing.[7] In all of my RPA reading, I have yet to see a cogent explanation of why it would be so hard for a supplier to demonstrate its cost savings to the recipient of a discriminatory price. After all, cost-of-goods-sold calculations represent a fundamental component of business accounting. The reason why the defense has been “virtually impossible” to meet in practice almost certainly rests with the challenged price having no supporting cost calculation as a basis in the first place. Where a supplier offers an arbitrary 20% discount to a favored customer, for example, no one should be surprised to find that it is “virtually impossible” for the supplier to cobble together data to show that it was cost-justified. But that does not condemn the defense; rather, it demonstrates that the supplier engaged in unjustified price discrimination.

2. Does the RPA prohibit “discounting,” resulting in higher prices to consumers?

The Cato Institute article proclaims that the RPA “inhibit[s] more efficient firms from receiving wholesale discounts,” and that “[i]f enforced again it would no doubt . . . result[] in higher prices for customers.” These are two familiar and related criticisms—that the RPA prohibits “discounts,” and that the result is higher prices to end consumers.

The notion that the RPA “prohibits discounts” is merely a framing device to support the criticism. Section 2(a) says nothing about “discounts;” what it prohibits is “discriminating in price.” The RPA can only be framed as prohibiting discounts if one assumes that the supplier’s baseline price is the higher price it charges its disfavored customers. But why should the price that the supplier unilaterally sets be deemed the baseline? One can just as easily declare that the baseline price is the one that the supplier negotiates with a strong buyer; Walmart or Costco for example. Under that framing device, what the Act prohibits is charging illegally higher prices to smaller businesses.

The effect on prices to end consumers follows suit. As Commissioner Bedoya noted, it has never been empirically demonstrated that prohibiting price discrimination results in higher prices to end consumers. But even with the lack of empirical support, the assumption that RPA enforcement “would no doubt . . . result[] in higher prices for customers” depends on supposing that if suppliers are forced to sell to competing purchasers at a single price, it would be their higher list-price, rather than their “Walmart price.” But surely a supplier’s largest customers aren’t mere price-takers, who will settle for whatever list price the supplier announces. Undoubtedly they would bargain for a lower price, and when that bargaining process is complete, the smaller purchasers would benefit from the same lower price. This is because “[i]f the bargaining is done by the stronger of two buyers, then the lower price becomes the price paid by everyone.”[8] If that is true, then prohibiting price discrimination gives all buyers access to the favored price, and “would no doubt” result in lower consumer prices to more people.

Of course there are numerous complications to a simplistic view that the proper “but for” price is the one given to the favored purchaser, and that all purchasers would get that price if the RPA were rigorously enforced. Most obviously, it seems likely that a supplier uses the higher prices it charges to its disfavored purchasers to subsidize the low prices it gives to the favored. But that is hardly a reason to suspect that the RPA results in higher prices to consumers on average. Rather, it seems consistent with the RPA’s fears: that in a world that permits price discrimination, smaller businesses will find themselves subsidizing the profitability of their larger competitors. More to the point of this article, however, is that I have yet to see any of the RPA’s legal critics even consider any of these issues, let alone attempt to rigorously analyze them.

Nevertheless, real world observation of RPA litigation supports the view that the proper baseline price is the one given to the big buyer. While I cannot speak as knowledgeably about the FTC’s historic enforcement actions, I can say that out of the hundreds of private-enforcement RPA cases I have read, the plaintiff has always demanded to be given the lower favored price, not demanded that its competitor be required to pay the plaintiff’s own higher price. In other words, success in those cases “would no doubt” result in lower prices, not higher ones, as the critics proclaim. That pattern is supported by the cases our firm has brought where the settlement has included a price component. Never once has the lower price given to the favored purchaser been taken away; it has always been the case that that lower price has been extended to our client.

* * *

In his September speech, Commissioner Bedoya quite rightly observed that nothing in the RPA or its legislative history suggested that Congress was concerned with promoting “efficiency.” Indeed (and while Commissioner Bedoya sagely refrained from making the point) the Congress that passed the RPA did not even express the purpose of ensuring the lowest possible prices to consumers. The Supreme Court has recently reiterated that the judiciary “is not free to substitute its preferred economic policies for those chosen by the people’s representatives.”[9] But since the Supreme Court has already largely substituted its preferred economic policies for those chosen by Congress in the antitrust realm, I fear that Commissioner Bedoya is ceding unnecessary ground in exhorting “a return to fairness,” as if fairness and efficiency are antipodes. While Commissioner Bedoya’s reading of congressional intent is undoubtedly correct, I sense that the FTC will have better luck in any future enforcement actions if—in addition to emphasizing the plain language of the Act—it pushes back strongly on the familiar condemnations of the Act, by pointing out that despite their endless repetition, they lack any empirical support.

Mark Poe is a co-founder of San Francisco-based Gaw | Poe LLP. Mr. Poe and his co-founder Randolph Gaw are classmates of the 2002 class of Stanford Law School, who worked at Morrison & Foerster, Wilson Sonsini, and O’Melveny & Myers prior to founding their own firm in 2014. The firm frequently litigates Robinson-Patman Act cases on behalf of “disfavored” wholesalers who cater to convenience stores and independent grocers.

[1] See https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/ftc-to-use-robinson-patman-act-as-an-antitrust-tool-to-target-large-retailer/#ixzz7otMtpJl0.

[2] See https://www.cato.org/blog/zombie-robinson-patman-act-doesnt-deserve-revival.

[3] See https://www.congress.gov/event/117th-congress/house-event/LC68134/text?s=1&r=91.

[4] See Robert Bork, The Antitrust Paradox (1978); Richard A. Posner, The Robinson-Patman Act, Federal Regulation of Price Differences, American Enterprise Institute (1976); Herbert Hovenkamp, Federal Antitrust Policy: The Law of Competition and Its Practice (3d ed. 2005).

[5] Hovenkamp, n.5, § 14.6a1.

[6] 15 U.S.C. § 13(a).

[7] See n.5, Posner at 41.

[8] Daniel P. O’Brien, The welfare effects of third-degree price discrimination in intermediate good markets: the case of bargaining, 45 RAND J. OF ECON. 92, 100 (2014).

[9] Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, 138 S. Ct. 1612, 1632 (2018) (Gorsuch, J.)

An overlooked impact of corporate mergers has been their adverse impact on the gender gap. Under the Consumer Welfare Standard, disparate impact on women and minorities is deemed irrelevant for antitrust policy. This deficiency merely reveals how the Consumer Welfare Standard illegitimately forces policymakers to ignore important features of social welfare in the interest of the merging parties. Merging parties contend that the severe layoffs that often accompany mergers as “efficiencies.” Quite the contrary, these layoffs cause human suffering and social dislocation.

Merger-related job cuts tend to target lower-level positions because they tend to be less specialized in nature and have the most employees. Historically, women and minorities have been over-represented in lower-level positions and under-represented in the highest-wage workforce. According to the Current Population Survey, women comprise 58 percent of the low-wage workforce, and women represent 69 percent of the lowest-wage workforce, referring to those occupations that typically pay less than $10 per hour.

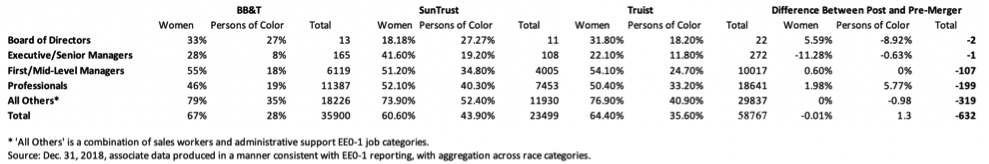

Consider the recent merger of the two banks BB&T and SunTrust. Using the Corporate Social Responsibility Reports from BB&T and SunTrust pre- and post-merger, I estimate that the gender composition across executive and senior managers, originally 28 percent and 42 percent for BB&T and SunTrust, respectively, was reduced to 22 percent post-merger. The antitrust status quo’s inability to address the gender difference, which produces such evident injury to female and minority labor, highlights the basic flaws of utilizing the Consumer Welfare Standard as the only compass to investigate and restrain anticompetitive activity.

Background on the Merger

On February 7, 2019, the boards of both BB&T and SunTrust announced the unanimous approvals to combine in merger of equals. Following discussion, the shareholders approved the merger of equals agreement on July 30, 2019. The parties contended that the merger was needed because of a changing financial landscape, which required increased scale and efficiency in the face of competition from larger banks. The combined entity was expected to benefit from cost savings and synergies (i.e., layoffs), as well as a broader range of products and services for customers.

The merger involved large banks. A Congressional Research Service examination of S&P Global Intelligence data reveals that, since 2010, in 88 percent of bank acquisitions, the acquired bank had assets of less than $1 billion, while in just one percent of acquisitions, the acquired bank had assets exceeding $10 billion. The BB&T-SunTrust merger is a clear outlier: SunTrust’s $215.5 billion in assets surpasses the second largest post-crisis purchase by more than double. Although it was one of the largest mergers in banking history, neither the Federal Reserve Board nor the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation challenged the merger. The Department of Justice ordered the divestiture of approximately $2.3 billion in deposits across seven local markets. While this divestiture ensured that banking consumers in Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia had continued access to competitively priced banking products, including small business loans, none of the federal agencies tasked with reviewing the merger addressed concerns of loss of diversity among the company or the loss of jobs due to said merger.

On December 6, 2019, the merger was officially consummated, and the company was renamed Truist Bank. The merger resulted in a merged corporation with a net value of $66 billion, and assets exceeding $400 billion. It also included around $330 billion in savings from over 10 million American families. The merged corporation is currently the sixth biggest bank in the United States, only preceded by JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo & Co, Citigroup, and U.S. Bancorp.

The Adverse Impact on Labor and on Diversity

The Corporate Social Responsibility forms filed by each company before and after the mergers raise several concerns regarding the loss of diversity among women and persons of color after the merger. In 2018, BB&T had 35,900 workers, while SunTrust had 23,499 workers. Before the merger, the two firms had a combined total of 59,399 employees. After the merger, Truist had a total of 58,767 employees. The workforce was thus reduced by 632 employees. Additionally, in 2018, BB&T had 67 percent women employees, and SunTrust had 61 percent women employees. Thus, the overall percentage of women employees in total between the two companies as a weighted average was 65.1 percent. In comparison, after the merger the percentage of women employees was reduced to 64.4 percent. The number of women in total between the companies decreased from 38,669 before the merger to 37,846 after the merger, for a reduction of 823. This means that the reduction in total workforce can be largely accounted for by the reduction in women employed. In fact, some women were replaced with men after the merger. Overall, we notice reductions of women employed in several positions, including executive and senior managers, sales workers, and administrative support.

The table below highlights the gender and minority distribution pre- and post-merger for the fiscal years 2018 and 2019.

According to these data, we find that there was a loss of diversity, expressed via the Persons of Color column in the Difference Between Post- and Pre-Merger section, among the Board of Directors, Executive and Senior Managers, as well as sales workers and administrative support. The total number of persons of color in the sales workers and administrative support category decreased by 427, using the same calculation method as for women.

These data also reveal that the biggest layoffs occur at lower-level positions such as sales workers, administrative support, and professionals. Only three individuals were laid off from the Board of Directors and Executive and Senior managers positions following the merger, while more than 500 individuals from the professionals, sales and administrative support categories were fired from their positions.

The harsh reality workers face when firms decide to merge goes against the main tenants proposed by welfare economics, which promotes policies that improve human well-being regardless of their race, gender, or ethnicity. But under the Consumer Welfare Standard, these harmful outcomes are deemed irrelevant. Even when monopsony is taken into account during a merger review, the impact to marginalized groups is often ignored. In addition, concentration can worsen diversity across firms and hinder women from climbing the professional ladder. In such situations, an emphasis on consumer welfare tips the balance in favor of the (white male) majority and against minority protected class status.

We need a merger standard that accounts for the impact of mergers on diversity and labor mobility for women. Obviously, antitrust enforcement is only one tool, but an important one. Output is not the only important social value and is far from a comprehensive measure of social welfare. In a political environment where women and persons of color are fighting for their rights, why has antitrust decided to turn a blind eye and favor the white male majority?

Laura Beltran is a Ph.D. student in the economics department at the University of Utah.

Should those of us who believe that the vigorous enforcement of the antitrust laws is in the public interest fear the rise of textualism? After all, textualism is the method of statutory construction that historically was pushed by Justice Scalia, and today it is usually used by the most conservative Supreme Court justices. In cases such as Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Court used textualism to overturn well established liberal precedent.

Yet, we shouldn’t fear textualism. It’s even possible that textualism could help promote robust antitrust enforcement. Consider, for example, the original, aggressively populist words of Section 7 of the Clayton Act. It prohibits mergers the effect of which “may be substantially to lessen competition or to tend to create a monopoly.” Notice the “may” language. (Also notice some aggressive language that is beyond the scope of this article, the “tend to monopolize” language. Also notice that the original language of Section 7 contains no efficiencies’ defense!)

Although some recent court decisions use “may” in the way that it usually is defined today, many decisions have re-articulated “may” in ways that give the term a very different meaning. For example, in United States v. Baker Hughes, Inc. (then) Circuit Court Judge Thomas affirmed a district court’s conclusion that “it is not likely that the acquisition will substantially lessen competition….” (boldface added). A similar articulation appeared in In re Cast Iron Soil Pipe & Fittings Antitrust Litig., a requirement that “the effect of the merger is to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.” (boldface added).

Other courts have re-formulated the “may” language in the context of implementing a three-part balancing test, including the 3rd Circuit’s 2022 opinion in FTC v. Hackensack Meridian Health, Inc.: “First, the FTC must establish a prima facie case that the merger is anticompetitive.” (boldface added). Recent opinions from the D.C. Circuit have substituted “is likely to” for “may,” including United States v. UnitedHealth Grp. Inc.: “[T]he government must show…that the proposed merger is likely to substantially lessen competition.” (boldface added).

These differing but all conservative re-formulations of “may” have been used in many other recent merger cases as well. They give rise to a question for which textualist analysis was well designed: What did “may” mean when the Clayton Act was passed in 1914? Did it mean the same thing as “may” means today? The same thing as “is likely to” or “will”?

A textualist analysis would attempt to determine what “may” meant when this word was used in the Clayton Act by starting – and in almost all cases ending – with the exact words of the statute. It would ascertain what “may” meant when the statute was enacted by giving this word the plain, ordinary, everyday, meaning it had at the time. But it would ignore the statute’s legislative history.

Justice Scalia’s treatise on textualism, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts, emphasized that modern enforcers and courts should analyze how the words and phrases in question were used in leading English language dictionaries of the period and (if applicable) also in contemporaneous legal dictionaries, legal treatises, and cases. Scalia helpfully provided lists of the English language dictionaries and legal dictionaries and treatises he considered “the most useful and authoritative” for various time periods. Two of these lists, for dictionaries and for legal treatises, covered the 1901-1950 period, which encompasses both the 1914 enactment of the Clayton Act and its major amendment in 1950.

All four of the English language dictionaries from this period Justice Scalia considered to be the “most useful and authoritative” defined “may,” but none defined the full phrase, “may be substantially.” What follows are the principle definitions contained in each dictionary. Some of these full definitions are quite lengthy.

The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia (1904) defined “may” principally as: “…. The principal uses are as follows: (a) To indicate subjective ability, or abstract possibility: rarely used absolutely …. (b) To indicate possibility with contingency….” The Oxford English Dictionary (1908) defined “may” principally as: “The primary sense of the verb is to be strong or able, to have power…. to have power or influence; to prevail (over)…. Expressing objective possibility, opportunity, or absence of prohibitive conditions; = CAN…. Expressing subjective possibility, i.e. the admissibility of a supposition. a. In relation to the future (may = ‘perhaps will’)….” Webster’s Second New International Dictionary (1934) defined “may” principally as, “To have power; to be able…. Liberty; opportunity; permission; possibility; as, he may go; you may be right…. Desire or wish…. Contingency….” Funk & Wagnalls New Standard Dictionary of the English Language (1943) defined “may” principally as: “To have permission; be allowed; have the physical or moral opportunity as, you may go; ….To be contingently possible; as it may be; you may get off….”

The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia explicitly said that, even though “may” could be used to mean only a theoretical or “abstract possibility,” may was “rarely used absolutely” in this way. Webster’s Second New International Dictionary similarly said, “Archaic Ability; competency; – now expressed by can….” The other two dictionaries did not, however, say that an absolutist or literal usage of “may” to mean even a tiny or theoretical possibility was archaic.

All four dictionaries, of course, defined “may” in terms of a possibility or contingency. None of these dictionaries used anything resembling an “is likely to” or “will” or any other type of “more likely than not” standard that was used in the cases cited earlier.

In addition, for the 1901–1950 period, Justice Scalia listed five legal dictionaries and treatises he considered to be “the most useful and authoritative.”. Three included relevant definitions of the word “may”. The Cyclopedia Dictionary of Law (1901) defined “may” as: “Is permitted to; has liberty to. The term is ordinarily permissive….” Legal Definitions by Benjamin Pope (1920) defined “may” principally as: “The word “may” and like expressions give, in their ordinary meaning, an enabling and discretionary power….. When a statute declares that something “may” be done, the language is, as a general rule, permissive….” Bouvier’s Law Dictionary (1940) defined “may” as “Is permitted to; has liberty to… Where there is nothing in the connection of the language or in the sense and policy of the provision to require an unusual interpretation, its use is merely permissive and discretionary….”

These legal dictionaries and treatises are thus consistent with the uses of “may” in the English language dictionaries of the period. None are consistent with the case law cited above.

Especially in light of “may” being used in conjunction with the phrase “be substantially to lessen competition,” it is highly unlikely that Congress wanted “may” to encompass mergers with only a tiny, theoretical chance of substantially lessening competition. The word “may” in Section 7 of the Clayton Act does not, however, limit the law’s prohibitions to mergers that are “likely” to or “are more likely than not” to or that “will” substantially lessen competition. A possibility or a modest probability should be enough.

This textualist analysis demonstrates that the “may” was intended by Congress to mean exactly what it means to a modern speaker of the English language. To the extent recent cases have deviated from Congressional intent, these cases should be overturned. If the courts accept the conclusions in this article the crucial question for believers in aggressive antitrust becomes: how much more vigorous would antitrust enforcement become? It is impossible to know.

To answer this question one should step back and ask the extent to which conservative judges would honestly and faithfully implement this statute as it was written even though they disagree with this wording? This dishonesty could happen even though judges are, of course, not supposed to substitute their own policy preferences for those of Congress.

Suppose, for example, a particular Circuit Court decided that a textualist reading of Section 7 should block all mergers with only a “non-trivial but modest possibility” of leading to a substantial lessening of competition? Would a conservative District Court judge presiding in that circuit who was sympathetic to corporate mergers find another, result-oriented way to dismiss a challenge to a merger? This type of judge could, for example, find a way to artificially broaden the definition of the market and thereby reduce defendant’s post-merger market share dramatically. Could a conservative judge deliberately find, on the basis of a paucity of evidence, that entry was easy and erroneously conclude that the post-merger firm had no ability to substantially affect competition?

Justice Kagan’s recent dissent in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency challenged the sincerity of the current Supreme Court’s embrace of textualism. She believes they allow their conservative values to override their allegiance to textualist analysis: