Advocates of all stripes will pounce on a Nobel prize in economics to promote their particular policy agenda. They find a strand of the work by the winning economist, or a snippet from the Nobel committee, spin it into their narrative, and voila, their pet theory is proven right. Even a Nobel prize winner says so!

We should take such claims with a grain of salt.

I confess that the initial coverage of this year’s economics prize, awarded on Monday to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for their work on the drivers of innovation, left me a little empty, as I couldn’t see any crisp policy implications. At least not at first.

But then Aghion was quoted in the New York Times, noting that he was optimistic about the prospects of artificial intelligence (AI), yet still “favored policies that promoted competition and did not consolidate power to just a few winners.” In a longer version of the story, he said “there needed to be competition policy so that AI innovators would not stifle rivals.”

Sometimes we don’t need to decipher the hidden meaning of a complex economic article written decades ago, or even the Nobel committee’s summary of an economist’s contributions. Sometimes we can just defer to what the economist actually says. Aghion is literally telling us that we’d be better off as a society if AI were competitively supplied, compared to a scenario in which AI is provided by a small handful of firms with near-monopoly power.

To take one possible scenario, imagine a “hypothetical” monopolist in the general search market with its own proprietary AI tool. It’s true that independent AI tools might shake up the general search market, assuming each AI tool competed on a level playing field. But if said search monopolist can preference its own AI tool to answer its users’ general search queries, then its search monopoly could be artificially extended.

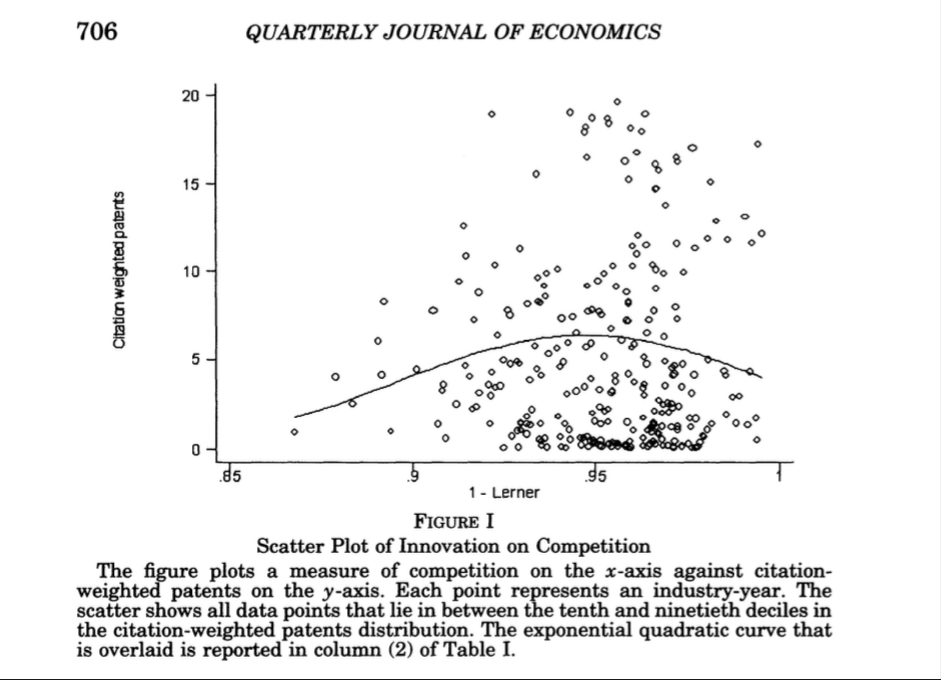

Indeed, Aghion’s and Howitt’s own research suggests that monopolists can be stifling for innovation. The figure below is reproduced from their 2005 Quarterly Journal of Economics article titled “Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship,”in which they studied the relationship between market power and innovation across UK industries.

The Y-axis plots the citation-weighted patents in an industry, a measure of innovation. The X-axis plots one minus the Lerner index or price-cost margin, a measure of competition in an industry. A value of one (far right along the X-axis) indicates perfect competition, as price equals marginal cost. Values below one indicate some degree of market power. As the figure shows, when industries become monopolized—one minus the Lerner index approaches zero—the amount of innovation decreases from its peak. In the words of the Nobel winners, “competition may increase the incremental profits from innovating, and thereby encourage R&D investments aimed at ‘escaping competition.’” The figure also indicates too much competition might be harmful for innovation as well.

The Pro-Monopolists Claim Victory

Despite this clear signal from one of the winners, the anti-anti-monopoly crowd, or more affectionately, the “pro-monopolists” as I like to call them, issued a press release trumpeting the exact opposite message—that this year’s Nobel prize stands for the proposition that antitrust enforcement is based on failed predicates and has swung too radically towards the interventionist side.

In a post titled “What Competition Scholars Should Know About the 2025 Economics Nobel,” ICLE’s chief economist Brian Albrecht argues that the work of Aghion and Howitt should cause a fundamental rethink on how we perform antitrust analysis:

The standard antitrust framework inherited from 1960s industrial organization focuses on market structure. Count the firms. Measure concentration. Assume that structure determines conduct, which determines performance. More firms mean more competition, which means lower prices and better outcomes. The U.S. Merger Guidelines embody this view with their use of Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) thresholds.

The Aghion-Howitt framework tells a different story. Competition is a process of innovation and displacement. Firms compete by trying to make better products, not just by cutting prices on existing ones. What matters is not the number of firms at any point in time, but whether new innovators can challenge incumbents. Market structure is an outcome of this competitive process, not just a cause of competitive behavior.

Notwithstanding Aghion’s own words calling for vigorous competition policy, Albrecht’s spin is a mischaracterization of how antitrust works in practice. Antitrust decisions don’t turn on simplistic concentration metrics in a market. In a single-firm monopolization case, concentration metrics are rarely used; when proving a defendant’s market power indirectly, what matters is the defendant’s share of the relevant market, along with evidence of of significant entry barriers. Alternatively, market power can be shown directly with evidence that the defendant raised prices over competitive levels or excluded rivals. But market power by itself doesn’t constitute a violation of antitrust law, as Albrecht intimates; plaintiffs must criticallyshow anticompetitive effects.

Even in merger cases, where concentration metrics play a role in establishing a presumption of anticompetitive effects, plaintiffs still must show anticompetitive effects owing to the merger,using entirely different models (such as upward-pricing pressure models). And merging parties can overturn the presumption with evidence of procompetitive effects. If Albrecht is saying that antitrust courts merely look at market structure to decide cases, he is attacking a straw-man.

Other Policy Implications

Let’s get back to reality. Here’s how the New York Times described the contribution of Aghion and Howitt, as summarized by the Nobel committee:

Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt shared the other half of the award for what the committee described as “the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction.” They built a mathematical model for growth, with creative destruction as a core element.

The committee described creative destruction as “an endless process in which new and better products replace the old.” They used the example of the telephone, in which each new version made the previous one obsolete, from the rotary dial phone in the early 1900s to today’s smartphones.

Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt’s work shows how economic growth can continue despite companies being sidelined by the innovation of other firms. Their work can support policymakers in creating research and development policies, the committee said.

The laureates’ work shows “we should not take progress for granted,” Kerstin Enflo, a member of the Nobel committee, said during a news conference in Stockholm. “Instead, society must keep an eye on the factors that generate and sustain economic growth,” she added. “These are science-based innovation, creative destruction and a society open for change.”

A narrow reading of this passage suggests that the policy implications of Aghion’s and Howitt’s work should be limited to “research and development policies.” Even under this lens, proponents of policies like subsidizing medical R&D, green energy technologies, or broadband infrastructure could claim a new quiver in their bow. To take broadband investment as an example, high speed internet connectivity generates spillovers across the economy and promotes growth by enablingapplications in myriad connected industries, as demonstrated here and here.

When announcing their award, the Nobel Prize committee noted that “Policy should support the innovation process,” and that “science-based innovation” was among the factors that “generate and sustain economic growth.” Upon receiving the award, Howitt reportedly said that the biggest advances in technological progress “have involved cooperation between governments, universities and businesses.” This is confirmed by countless examples of public investment pushing technology forward. One notable recent example was Operation Warp Speed, a public investment into Covid-19 vaccine development and production. Another public investment, the BEAD Program, allocated billions to states to expand high-speed Internet access.

Would this year’s Nobel prize winners embrace other interventions in the economy? Say, to permit publishers to collectively bargain against Internet behemoths to ensure that content does not vanish? Perhaps, given their apparent fondness for competition and government programs. But rather than reading the tea leaves, we could just ask them. Or we can recognize that there are limits to what a Nobel prize can say about our pet policy ideas.