Delta president Glen Hauenstein told investors in July that AI-based pricing is currently used on about 3 percent of its domestic network, and that the company aimed to expand AI pricing to 20 percent of its network by the end of the year. This is bad news for flyers, and given the particular way Delta is accessing the technology, is particularly bad for competition.

Airlines have been using “dynamic pricing” for decades, which entails setting fares based on common (as opposed to individualized) factors like demand, timing, real-time supply, and pricing by competitors. A spokesperson for Delta insists the new technology is merely “streamlining” its dynamic pricing model.

Personalized pricing, made possible via surveillance and AI, is distinct from dynamic pricing, in that the former allows a firm to condition pricing on the circumstances of the customer. Hence, two people shopping for airfares at the same time might see different prices based on things like travel purpose (business or leisure), income estimates, browsing behavior, ticket purchase history, website used, or type of device used.

To implement the new technology, Delta is working with Fetcherr, an Israeli-based GenAI pricing startup whose clients include other airlines like Virgin Atlantic and WestJet, to power the pricing changes. Alas, the three carriers share overlapping routes. From London, Virgin Atlantic flies to several U.S. destinations, including Atlanta, Boston, Miami, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, New York, Orlando, and Washington D.C. Delta also operates flights from London to many of those same U.S. cities, including Atlanta, Boston, Los Angeles, and New York. WestJet has expanded its network into the United States, including to such destinations as Anchorage, Atlanta Minneapolis, Raleigh, and Salt Lake City. (Some of these routes are in partnership with Delta.) Economists and antitrust authorities recognize that there could be anticompetitive effects if common pricing algorithms lead to collusion. Check out the DOJ’s antitrust case against RealPage, in which landlords are alleged to have to turned over their pricing decisions to a common algorithm (RealPage).

During the company’s second-quarter earnings, Delta CEO Ed Bastian noted “While we’re still in the test phase, results are encouraging.” Hauenstein called the AI a “super analyst” and results have been “amazingly favorable unit revenues.” These boasts, aimed at investors as opposed to consumers, mean that AI-based pricing is raising profits—else the results would be ambiguous or discouraging. And those extra profits are likely coming off the backs of consumers. And as we will soon see, rising unit revenues means that AI-based pricing is not leading to price reductions on average, contra the predictions of price-discrimination defenders.

Price Discrimination Is Bad for Consumers, Even When Implemented Unilaterally

Economic textbooks are filled with passages claiming that the welfare effects of price discrimination are ambiguous. It’s worth revisiting the key assumption that permits such an innocuous characterization—namely, an increase in output. As we will see shortly, this assumption isn’t easily satisfied in the airline industry.

Consumer welfare or “surplus” is recognized as the area underneath the demand curve bounded from below by the price. For a particular customer, surplus is the difference between her willingness to pay (WTP) and the price. Importantly, when it comes to first-degree price discrimination—charging each consumer her WTP—all consumer surplus is transferred to the producer, meaning consumers receive no benefit from the transaction beyond the good itself.

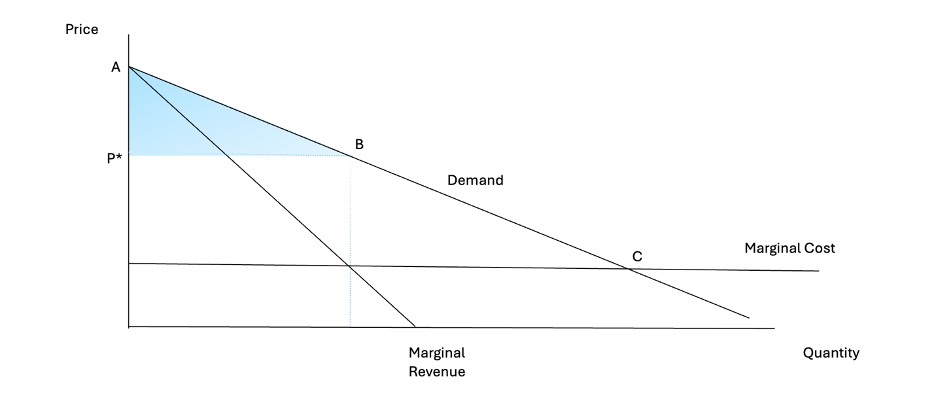

Let’s start with the basics. The figure below shows what happens when a firm facing a downward-sloping demand—an indicator of market power—is constrained to charging a single, uniform price to all comers. The profit-maximizing uniform price, P*, is found at the intersection of the marginal revenue and marginal cost curve, and then looking up to the demand curve to find the corresponding price.

Even at the profit-maximizing uniform price, P*, the firm with market power leaves some consumer surplus on the table, equal to the area of the triangle, ABP*. This failure to extract all consumer surplus motivates many anticompetitive restraints that we observe in the real world, such as bundled loyalty discounts. Another way to extract that surplus is, if possible, to charge each consumer along the demand curve between A and B her WTP. And that’s where AI-based personalized pricing comes in. Consumers along that portion of the demand curve are clearly worse off relative to a uniform pricing standard. The only consumer who is indifferent between the two regimes is the one whose WTP is just equal to P*, situated at point B of the demand curve.

Defenders of price discrimination are quick to point out that the price-discriminating firm can reduce its price, relative to P*, to customers on the demand curve from B to C, bringing fresh consumers into the market (who were previously priced out at P*) and expanding output. After all, they claim, there is incremental profit to be had there, equal to the difference between the WTP (of admittedly low-value consumers) and the firm’s marginal cost. There are at least two practical problems, however, with this theoretical argument as applied to airlines.

First, this argument presumes that airline capacity can be easily expanded. But an airline can only enhance output in a handful of costly ways. An airline can add more planes, which are not cheap, or more seats per plane, decreasing the quality of the experience for all passengers. An airline could also add more flights per day, but this too is costly because the airline must secure permissions from the airport at the gates.

Second, as noted above, the customers between B and C along the demand curve are the low-valuation types, who are not coveted by legacy carriers like Delta or United. These low-valuation and budget-conscious customers tend to fly (if at all) on the low-cost carriers and ultra-low-cost carriers like Southwest and Spirit, respectively. Serving these customers, as opposed to extracting greater surplus from high-valuation customers, is likely less attractive to Delta, especially if doing so would compromise the quality of existing customers (through, for example, cramming more seats on a plane), or would put downward pressure on prices of other items that are sold on a uniform basis (e.g., in-flight WiFi or alcoholic drinks).

Even if you don’t accept these practical arguments, it bears repeating once more that under first-degree price discrimination, there is no consumer surplus, even at the expanded output. So expanded output here is nothing to cheer about, unless you are an investor in the airlines or work as an airline lobbyist or consultant. And if there’s any doubt on the price effects from AI-based pricing, recall the boast from Delta’s executive—unit revenues are rising, which can’t happen if Delta is using the technology to drop prices on average to customers.

Price Discrimination Is Even Worse for Consumers When Implemented Jointly with Rivals

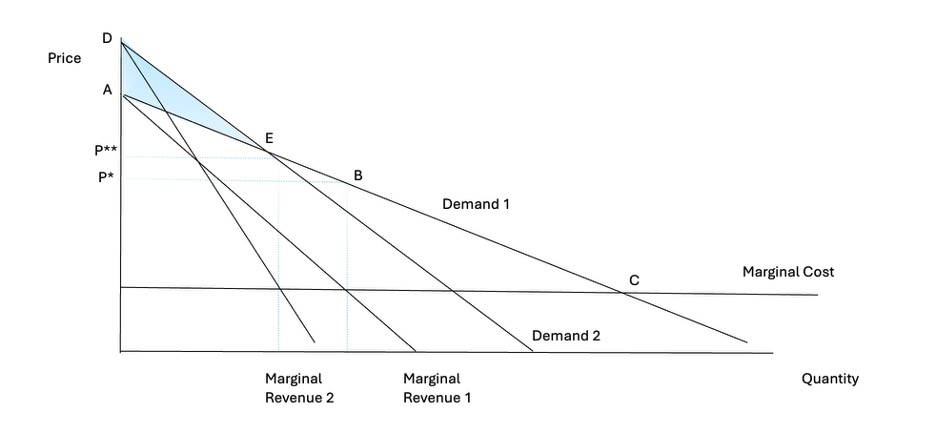

If this weren’t bad enough, there’s a knock-on effect from AI-based personalized pricing, especially if the technology vendor is also supplying the same pricing assistance to Delta’s rivals. Recall that Delta uses a pricing consultant that is also advising airlines with overlapping routes with Delta. In that case, the common pricing algorithm can facilitate collusion that would other not be possible. We can return to our figure to see how collusion can make consumers even worse off relative to discriminatory pricing.

Relative the original demand curve (Demand 1), the demand when prices are set via a common pricing algorithm (Demand 2) is less elastic, meaning that an increase in price does not generate as large a reduction in quantity. In lay terms, the demand is steeper. This rotation of the demand curve, made possible by weakening an outside substitute via collusion, causes the uniform profit maximizing price to rise above P* to P**. And this higher price opens the possibility of additional surplus extraction via price discrimination, equal to the area DAE, for the highest-value customers.

Where We Do Go from Here?

At this point, we have two different policy choices. The first is to pursue an antitrust case against Delta and Fetcherr. The problem with antitrust—and I make this argument against my own economic interests as an antitrust economist—is that such a case against Delta would not be resolved for years. The DOJ’s case against RealPage was filed nearly a year ago (August 2024), and we’ve seen little progress. In complex litigation, the defendants need time to produce voluminous data and records in response to subpoenas, the plaintiffs’ economists will have to understand those data and build econometric models that will be subjected to massive scrutiny by even more economists, there will be hearings, motions for summary judgment and to exclude testimony, and then a trial.

The second intervention is to ban, via regulation at either the city or federal level, the use of common pricing algorithms for airlines or more broadly. Similar bans have been imposed by cities against RealPage and Airbnb, which also has been accused of employing a common algorithm (and the subject of a forthcoming piece). Senators Ruben Gallego of Arizona, Mark Warner of Virginia, and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut sent a letter to Delta on July 22 correctly asserting the harms from Delta’s AI-based pricing, which will “likely mean fare price increases up to each individual consumer’s personal ‘pain point’ at a time when American families are already struggling with rising costs.” A senate hearing could be in order. But Delta won’t back off from this approach unless and until it perceives the threat of regulation to be credible.

Of the two options, I prefer the latter. With luck, Congress will too!