I love eggs. I really do. There was a year in law school where I religiously made and ate an egg sandwich for breakfast every day. To this day, I believe an egg fried in olive oil until the yolks are jammy and the edges are crispy is a perfect food.

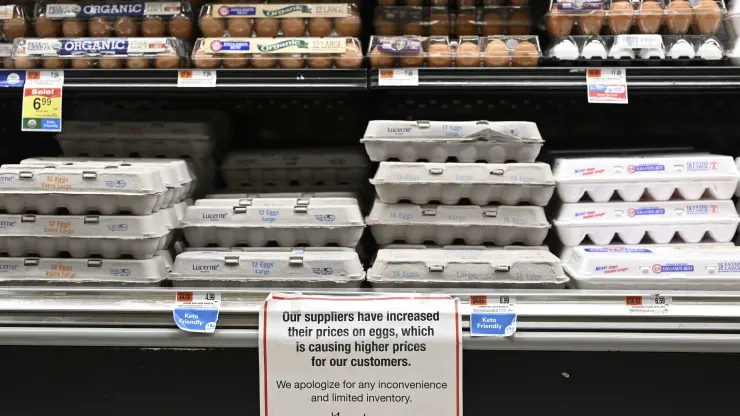

Since last year, however, my egg-loving style has been cramped. As everyone knows, the price of eggs at the grocery store more than doubled in 2022, increasing from $1.78 a dozen in December 2021 to over $4.25 in December 2022. This 138-percent increase in egg prices far outstripped the 12-percent increase Americans saw in grocery prices generally over the same period. And some Americans have had it much worse, as average egg prices reached well over $6 a dozen in states ranging from Alabama to California and Florida to Nevada.

What’s behind the skyrocketing retail price of the incredible edible egg? Well, for one thing, the skyrocketing wholesale price of that egg. Between January 2022 and December 2022, wholesale egg prices went from 144 cents for a dozen Grade-A large eggs to 503 cents a dozen. This was the highest price ever recorded for wholesale eggs. Over the entire year, wholesale egg prices averaged 282.4 cents per dozen in 2022. When we consider that average retail egg prices for the same year were only about 3 cents higher at 285.7 cents per dozen, it becomes clear that the primary contributor to rising egg prices at the grocery store has been the dramatic increase in the wholesale prices charged by egg producers.

If this gives you hope that relief might be around the corner because you’ve heard something about a recent “collapse” in wholesale egg prices, sadly your hope would be misplaced. Despite this much-ballyhooed collapse, the average wholesale egg price has simply gone from 4-to-5 times what it was in January of last year to 2-to-3 times that number. If that weren’t enough, prices are expected to spike again when egg demand picks up in the run-up to Easter. Ultimately, the USDA is projecting that the average wholesale egg price in 2023 will be 207 cents a dozen—or only about 25% lower than the average price for 2022. So much for a collapse.

Are you wondering who sets these wholesale prices? Why, an oligopoly, of course. The production of eggs in America is dominated by a handful of companies led by Cal-Maine Foods. With nearly 47 million egg-laying hens, Cal-Maine controls approximately 20% of the national egg supply and dwarfs its nearest competitor. The leading firms in the industry have a history of engaging in “cartelistic conspiracies” to limit production, split markets, and increase prices for consumers. In fact, a jury found such a conspiracy existed as recently as 2018, and a wide-ranging lawsuit was brought just a couple of years ago accusing several of the largest egg producers (including Cal-Maine) of colluding to increase prices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When asked about the multiplying price of their product, these dominant egg producers and their industry association, the American Egg Board, have insisted it’s entirely outside their control; an avian flu outbreak and the rising cost of things like feed and fuel, they say, caused egg prices to rise all on their own in 2022. And, sure enough, those were real headaches for the egg industry last year—about 43 million egg-laying hens were lost due to bird flu through December 2022, and input costs for producers certainly increased over 2021 levels. As my organization, Farm Action, detailed in letters to federal antitrust enforcers last month, however, the math behind those explanations for the steep increase in wholesale egg prices just doesn’t add up.

The reality, we argued, is that wholesale egg prices didn’t triple in 2022, and aren’t projected to stay elevated through 2023, because of “supply chain, ‘act of God’ type stuff,” as one industry executive has tried to spin it. Rather, the true driver of record egg prices has been simple profiteering, and more fundamentally, the anti-competitive market structures that enable the largest egg producers in the country to engage in such profiteering with impunity.

Is it really just profiteering? Yes, it’s really just profiteering.

According to the industry’s leading firms, rising egg prices should be blamed on two things: avian flu and input costs. We can stipulate for the sake of argument that, if a massive amount of egg production and, hence, potential revenue were lost due to avian flu, the largest producers would be justified in trying to recoup some of that lost revenue by raising prices on their remaining sales. Likewise, if there were a sharp rise in egg production costs, we can stipulate that producers would be justified in trying to pass them on to wholesale customers. But was there a nosedive in egg production? Did the cost of egg inputs multiply dramatically? Short answer: No, and No.

The bottom line on the avian flu outbreak is that it simply did not have a substantial effect on egg production. Although about 43 million egg-laying hens were lost due to avian flu in 2022, they weren’t all lost at once, and there were always over 300 million other hens alive and kicking to lay eggs for America. The monthly size of the nation’s flock of egg-laying hens in 2022 was, on average, only 4.8 percent smaller on a year-over-year basis. If that isn’t enough, the effect of losing those hens on production was itself blunted by “record high” lay rates throughout the year, which were, on average, 1.7 percent higher than the lay rate observed between 2017 and 2021. With substantially the same number of hens laying eggs faster than ever, the industry’s total egg production in 2022 was—wait for it—only 2.98 percent lower than it was in 2021.

Turning to input costs, it’s true they were higher in 2022 than in 2021, but they weren’t that much higher. Farm production costs at Cal-Maine Foods—the only egg producer that publishes financial data as a publicly traded company—increased by approximately 20 percent between 2021 and 2022. Their total cost of sales went up by a little over 40 percent. At the same time, Cal-Maine produced roughly the same number of eggs in 2022 as it did in 2021. If we take Cal-Maine Foods as the “bellwether” for the industry’s largest firms, we can be pretty sure that the dominant egg producers didn’t experience anywhere near enough inflation in egg production costs to account for the three-fold increase in wholesale egg prices.

Against the backdrop of these facts, the industry’s narrative simply crumbles. It’s clear that neither rising input costs nor a drop in production due to avian flu has been the primary contributor to skyrocketing egg prices. What has been the primary contributor, you ask? Profits. Lots and lots of profits.

Gross profits at Cal-Maine Foods, for example, increased in lockstep with rising egg prices through every quarter of the last year. They went from nearly $92 million in the quarter ending on February 26, 2022, to approximately $195 million in the quarter ending on May 28, 2022, to more than $217 million in the quarter ending on August 27, 2022, to just under $318 million in the quarter ending on November 26, 2022. The company’s gross margins likewise increased steadily, from a little over 19 percent in the first quarter of 2022 (a 45 percent year-over-year increase) to nearly 40 percent in the last quarter of 2022 (a 345 percent year-over-year increase).

The most telling data point, however, is this: For the 26-week period ending on November 26, 2022—in other words, for the six months following the height of the avian flu outbreak in March and April—Cal-Maine reported a five-fold increase in its gross margin and a ten-fold increase in its gross profits compared to the same period in 2021. Considering the number of eggs Cal-Maine sold during this period was roughly the same in 2022 as it was in 2021, it follows that essentially all of this profit expansion came from—you guessed it—higher prices.

But is this an antitrust problem? Yes, it’s an antitrust problem.

On their own, these numbers plainly show that dominant egg producers have been gouging Americans, using the cover of inflation and avian flu to extract profit margins as high as 40 percent on a dozen loose eggs.

Some agriculture economists and market analysts, however, have questioned whether this price gouging should raise antitrust concerns. The dramatic escalation in egg prices over the past year, they’ve argued, has just been “normal economics” at work. Per Angel Rubio, a senior analyst at the industry’s go-to market research firm, Urner Barry, the runaway increase in wholesale egg prices was simply a function of the “compounding effect” of “avian flu outbreaks month after month after month.” These outbreaks repeatedly disrupted egg deliveries, he presumes, driving customers to assent to spiraling price demands from alternative suppliers. In a blog post on Urner Barry’s website, Mr. Rubio further hypothesized that jittery customers may have “increased their ‘normal’ purchase levels to secure more supply,” goosing up prices even higher.

There are several reasons to doubt this theory of the case. To begin with, Mr. Rubio’s analysis presumes that avian flu outbreaks caused significant disruptions in the supply of eggs even though, as discussed above, the aggregate production data suggests that was not the case. But let’s assume that there were supply disruptions, and that these disruptions did lead to a glut of demand for reliable suppliers, giving them pricing power. If that were the case, it would stand to reason that Cal-Maine—which did not report a single case of avian flu at any of its facilities in 2022—had an opportunity to sell a whole lot more eggs in 2022 than in 2021, and to sell them at record-high profit margins. But Cal-Maine didn’t sell a whole lot more eggs. It sold roughly the same number of eggs. If Mr. Rubio’s theory were right, why did Cal-Maine leave money on the table?

Once we start applying this question to the pricing and production behavior of the egg industry’s dominant firms more broadly, a whole variety of competition red flags start cropping up

The red flags—they multiply!

Let’s talk about pricing first. In a truly competitive market, one would have expected rival egg producers to respond to a near-tripling of average market prices with efforts to undercut Cal-Maine’s skyrocketing profit margin and capture market share. Alas, that did not happen. In researching Farm Action’s letter to antitrust enforcers, we found no evidence of aggressive price competition for business among the largest egg producers. Yet everything about the mechanics of egg sales suggests that they should be competitive. Wholesale customers generally buy their eggs directly from producers. Long-term or exclusive contracts for egg supplies are rare. And the price of eggs in each purchase is individually negotiated. In other words, for each delivery of eggs they need, a wholesale customer is in all likelihood free to shop around and give rival suppliers an opportunity to undercut their incumbent supplier. Given this fluid sales environment, how did Cal-Maine manage to raise prices so much that its profit margin quintupled in one year without any other major producer coming to eat its lunch?

Another head-scratcher has been how the industry has managed to throttle production in the face of sustained high egg prices. As early as August of last year, the USDA was observing that favorable conditions existed, both in terms of moderating input costs and record-high egg prices, for producers to invest in expanding their egg-laying flocks. Yet such investment never materialized.

Even as prices reached unprecedented levels between October and December of last year, the number of eggs in incubators and the number of egg-laying chicks hatched by upstream hatcheries both remained flat, and were even below 2021 levels in December. As the year drew to a close, the USDA observed that “producers—despite the record-high wholesale price—are taking a cautious approach to expanding production in the near term.” The following month, it pared down its table-egg production forecast for the entirety of 2023—while raising its forecast of wholesale egg prices for every quarter of the coming year—on account of “the industry’s [persisting] cautious approach to expanding production.”

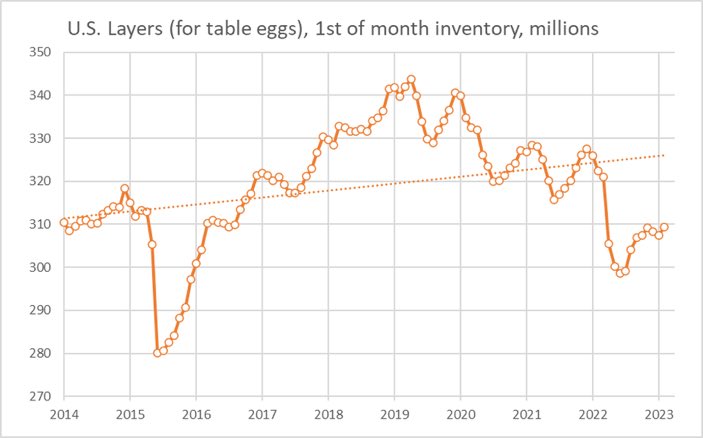

Because of this “caution” among egg producers, the total number of egg-laying hens in the U.S. has recovered from the losses caused by avian flu outbreak of 2022 at less than one-third of the pace it recovered from the (relatively more severe) avian flu outbreak of 2015, according to data from the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service. At its lowest point in the aftermath of the 2022 avian flu outbreak—in June of last year—the egg-laying flock counted a little under 300.5 million hens, or around 30 million (or 9%) fewer hens than it started the year with (330.8 million). For comparison, at its lowest point following the 2015 outbreak—which was also in June of that year—the egg-laying flock totaled 280.2 million and had nearly 35 million (or 11%) fewer hens than it did at the start of 2015 (315 million).

As you can see from the chart above (Fig. 1), in 2015, it took the industry less than 8 months to rebuild the egg-laying flock from its June low point; by the end of February 2016, producers had added over 30 million hens, bringing the total size of the egg-laying flock back up to 310.2 million. Contrast this pace of flock recovery between 2015 and 2016 with the pace of recovery we’ve seen over the past year. In the 8 months that have passed since June of last year, the industry has added less than 9 million hens—leaving the flock at an anemic 309.4 million at the start of February 2023.

On its own, this comparison shows that large egg producers almost certainly could have rebuilt their hen flocks in the wake of last year’s avian flu outbreaks much faster than they have. When considered alongside the fact that, in 2015, the monthly average wholesale price reached its highest point in August and never exceeded $2.71 per dozen, the sluggishness of the 2022-2023 recovery becomes objectively suspicious. According to Urner Barry, in 2015, wholesale egg prices rose 6-8% for every 1% decrease in the number of egg-laying hens caused by the avian flu; that is barely half the 15% price increase for every 1% decrease in hens observed last year. The monthly price for a dozen wholesale eggs in 2022 cleared the 2015 high of $2.71 per dozen as early as April, and stayed at comparable or higher levels through the rest of the year. And yet, egg producers have been “cautiously” adding hens at a third of pace they did in 2015-2016 since June of last year. What gives?

As Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Katie Porter noted in recent letters to dominant egg producers seeking answers about ballooning prices, producers appear to be “impervious to the basic laws of supply and demand.” This is the case not only in terms of their willingness to invest in new capacity, but also in terms of their willingness to utilize existing capacity. The rate at which hens lay eggs is the basic measure of flock productivity in the industry. Several factors can affect lay rates, including hen genetics and age, but within physical limits, producers can speed or slow egg-laying by their hens through nutrition, lighting, and other flock management choices. Yet, even as millions of hens were being lost to avian flu and eggs were fetching unprecedented prices last year, producers seemed to make choices that depressed, rather than maximized, their remaining hens’ lay rates.

The average table-egg lay rate reached its highest level ever (around 83.5 eggs per 100 hens per day) in the early, most severe, months of the avian flu epidemic—between March and May of last year—but then it nosedived. By June, the national average lay rate had dropped to about 82.5 eggs per 100 hens per day. This was consistent with seasonal trends in years past; it’s typical for lay rates to moderate as Spring turns to Summer. What happened after June, however, was curious. Normally, the average lay rate would start climbing again in July and stay on an upward trend through the end of the year, with the strongest lay rates often reported in the last 2 or 3 months of the year. In 2022, however, the opposite occurred. Lay rates flat-lined from June through the Fall before dipping to their weakest level in the last three months of the year. In other words, during the exact period when egg prices were hitting their stride—the last six months of 2022—the industry somehow managed to orchestrate a wholesale deviation from historical trends in the direction of getting fewer eggs out of the hens they already had.

If it walks like a cartel and swims like a cartel, maybe it’s a cartel?

Together, these dynamics of throttled production and unrestrained pricing are unmistakable red flags that deserve investigation by enforcers. Take Cal-Maine as an example again. They are the leader in a mostly commoditized industry. They presumably have the most efficient operations and the greatest financial power of any firm in the industry—allowing them to stand up hen capacity as fast as anyone and sell at competitive prices to capture unmet or up-charged demand. Instead of doing that, however, it appears they simultaneously abandoned price competition and refrained from expanding production to satisfy demand last year. This begs the question: What made Cal-Maine so confident that other large producers wouldn’t produce more eggs and undercut its prices? More to the point, why didn’t they?

Whatever the answers to these questions might be, this much is clear: Cal-Maine behaved as if its dominant position were entrenched, and its strategy worked. As rival egg producers have gone along instead of competing on price and production, the industry has been able to sustain elevated egg prices from one year to the next without any legitimate justification. Even as egg prices have started ameliorating this year, the USDA is still forecasting an average wholesale price for 2023 that is 70-to-80% higher than the 2021 average, suggesting that whatever “bottom” egg prices might reach this year will, in all likelihood, be at least an order of magnitude higher than 2021 levels.

This pattern of behavior by dominant egg producers over the past year is consistent with longstanding research beginning in the 1970s—from Blair (1972) to Sherman (1977) to Kelton (1980)—on how leading firms in consolidated industries “administer prices” to achieve higher-margin “focal points” during economic shocks and periods of high inflation. And, make no mistake, the egg industry is consolidated. While the top 10 egg producers control 53%—and Cal-Maine alone controls 20%—of all egg-laying hens in the U.S., these numbers understate concentration in actual egg markets. Smaller egg operations (the ones that control the other 47% of America’s hens) tend to produce specialty, not conventional, eggs for sale at premium price points; as such, they typically have neither the scale nor the capacity to supply national grocery chains with the conventional eggs bought by most consumers. Only the largest egg producers can fill this need—a fact that likely makes the submarket for conventional eggs sold to national customers substantially more concentrated than the total egg supply. Was it pure coincidence that prices barely climbed In the fragmented specialty-egg segment but skyrocketed in the consolidated conventional-egg segment?

The honest answer is that I don’t know. In the end, I’m just a country lawyer with a laptop and a love for fried eggs. But smart people at the Boston Fed, the University of Utah, and a few other places have recently shown—empirically, I’m told—that it’s easier for competitors to coordinate for higher profits during a crisis when their industry is concentrated. Maybe that’s what happened here. Maybe it’s not. The only people who can find out for sure—and get the American people some restitution if it is what happened—are the fine public servants at the Federal Trade Commission, the Justice Department Antitrust Division, and state Attorneys General offices across the country. They should do nothing less.

Conclusion

For nearly 12 months now, dominant egg producers have demonstrated their ability to charge exorbitant prices for a staple we all need for no reason beyond having the power to do it. The “philosophy” of our antitrust laws, as Justice Douglas once reminded his colleagues on the Supreme Court, is that such power “should not exist.” With hundreds of millions of dollars missing from Americans’ pockets to enrich the profits of a handful of robber barons in the egg industry, antitrust enforcers owe the public a duty to investigate, and to see to it that the nation’s laws are enforced—even against entrenched giants.

Basel Musharbash is Legal Counsel at Farm Action, a farmer-led advocacy organization dedicated to building a food and agriculture system that works for everyone rather than a handful of powerful corporations. Basel is also the Managing Attorney of Basel PLLC, a mission-driven law firm in Paris, Texas, focused on the intersection of community development and antitrust law.