Since the launch of ChatGPT back in November of 2022, what was once a concept confined to Sci-Fi novels has now certifiably hit the mainstream. The highly visible advances in artificial intelligence (AI) over the past few years have either been awe-inspiring or dread-inducing depending on your perspective, your occupation, and maybe how much Nvidia stock you owned before 2023. Many white-collar workers now fear that they may face the same job-displacing effects of automation that has plagued their blue-collar peers over the past several decades.

Nevertheless, at least one powerful constituency is absolutely thrilled with the rise of AI and is betting big on its success: Big Tech. Microsoft, currently the second most valuable company in the world with a mind-boggling $3.7 trillion market cap, is a leading AI zealot. This fiscal year alone, Microsoft plans to invest over $80 billion in AI-related projects.

As one of its big selling pitches to investors and consumers, Microsoft argues that AI has prompted massive efficiency gains internally, including eliminating a staggering 36,000 workers since 2023. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella estimated that as much as 30 percent of the company’s code is now written by AI. Mr. Nadella, of course, has a lot riding on convincing shareholders and consumers that AI is a big deal. So, to what extent this claim is legitimate, or pure marketing fantasy, is uncertain. A recent working paper authored by Microsoft researchers and academics analyzes the productivity increases in (non-terminated) software developers who use AI tools. The authors find that developers using AI tools saw an average 26 percent increase in their productivity. If such experimental results generalize to the broader labor market, AI will certainly have a dramatic impact. Despite evident benefits towards companies from this productivity boon whether workers themselves stand to gain remains uncertain.

A Look into Software Developers’ Compensation

AI models capable of assisting with writing and coding tasks have existed for a couple of years now. Taking Mr. Nadella’s statements at face value, such models enjoy widespread utilization by developers and coders working for Big Tech. As such, if workers—and not just their employers—stand to benefit from AI, then worker compensation should reflect at least some evidence of these productivity gains.

Simple economic models of the labor market suggest that a technology that boosts the marginal productivity of labor will cause a concomitant increase in worker pay. After all, in competitive labor markets, workers should capture 100 percent of their marginal revenue product (MRP), which increases with productivity, though such an outcome rests upon a strong and often-violated assumption that the relevant labor market is perfectly competitive. When an employer has buying power, it can drive a wedge between the worker’s MRP and her wage. In lay terms, this means the employer can appropriate value created by the worker without sharing in the gains, the Pigouvian definition of exploitation. Thus, the extent to which workers benefit from this AI-induced productivity remains unclear. (In addition, a monopsony reduces employment relative to a competitive labor market; Microsoft’s mass firings since its acquisition of Activision in 2023 is also consistent with the exercise of monopsony power.)

While a recent article in The Economist highlights how the AI boom has led to some “superstar coders” seeing their “pay [] going ballistic,” this subset of workers represents a tiny sliver of the total labor market of developers. In that same article, The Economist also produced a graph showing a dramatic slowdown in hiring—job postings for software developers have dropped by more than two-thirds since the beginning of 2022. To understand how AI is affecting workers, we need to look at the labor market at large. Unfortunately, our analysis suggests that software developers have not yet benefited (and may never fully benefit) from their increase in productivity.

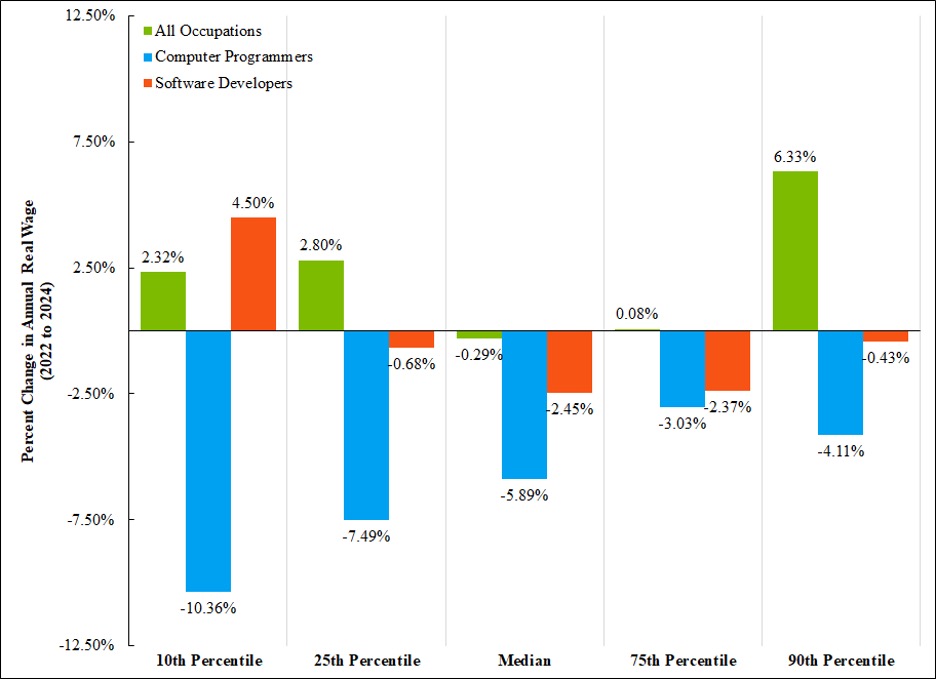

Figure 1 below takes the broadest look at how all software developers and computer programmers in the United States have (or have not) benefited from the rise in AI. The results are not pretty: While 2022 inflation has hit all workers hard, eroding much of their nominal wage increases, both computer programmers and software developers are faring much worse than the average worker. Per the BLS, the median wage of computer programmers decreased by 5.89 percent between 2022 and 2024.

Figure 1: Real Wages Are Flat for Most Workers, But Have Declined for Programmers and Developers

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics Annual Report; CPI sourced from FRED. Notes: We transformed this nominal data using CPI to be in 2024 dollars. Hence, this chart shows the real change in wages between 2022 to 2024 (i.e., accounting for inflation). 2024 is the most recent data release, and the 2024 data are not inclusive of data from Colorado.

Not even the top ten percent of software developers, including the “superstar coders” as dubbed by The Economist, appear to be thriving. Figure 1 also shows that the highest paid computer programmers (90th percentile) saw their real wages fall by 4.11 percent.

Workers for Big Tech fared no better. Indeed, the percentage change in the median compensation for software engineers employed by Big Tech effectively mirrors that reported in Figure 1—the median software engineer saw a 2.22 percent decrease in their real wages from 2022 to 2024 per data from Levels.fyi.

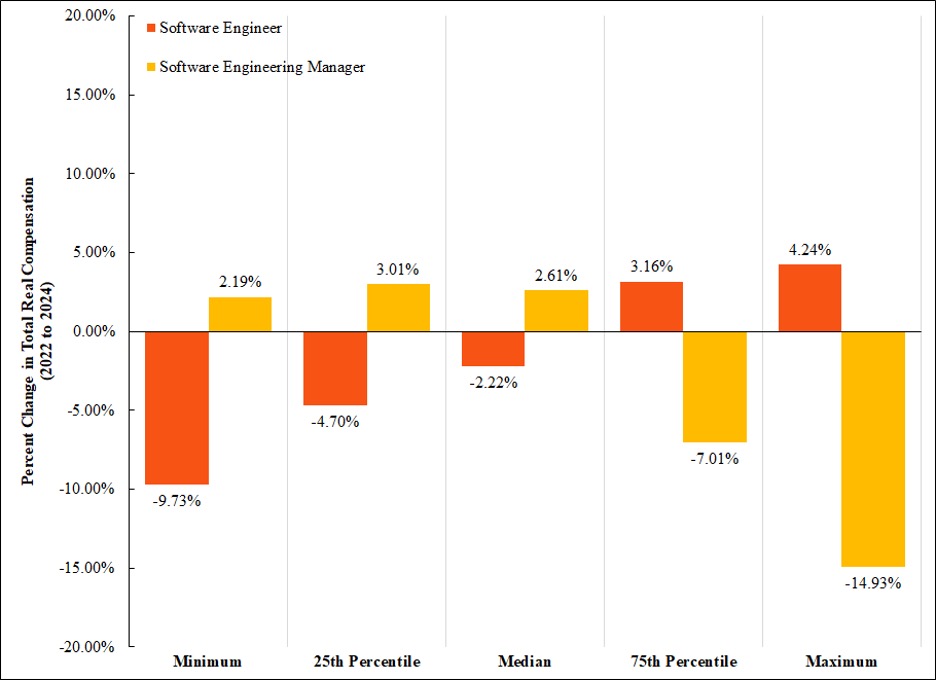

Figure 2: Software Engineers Working Big Tech Also Have Not Seen a Dramatic Rise in Wages

Source: Levels.fyi 2024 and 2023 year-end reports; CPI sourced from FRED. Notes: Levels.fyi collects self-reported data “for the top paying tech companies and locations.” Total compensation is inclusive of base salaries, stock grants, and bonuses. Note that Levels.fyi’s trend table has slightly different median compensation estimates than the box charts that we source our data from. It is unclear what causes this discrepancy. We transformed this nominal data using CPI to be in 2024 dollars. Hence, this chart shows the real change in total compensation between 2022 to 2024 (i.e., accounting for inflation).

At the very least, we see evidence that software engineering managers (depicted in yellow) have seen their compensation rise (by 2.61 percent), though nowhere near their supposed AI-powered productivity increase.

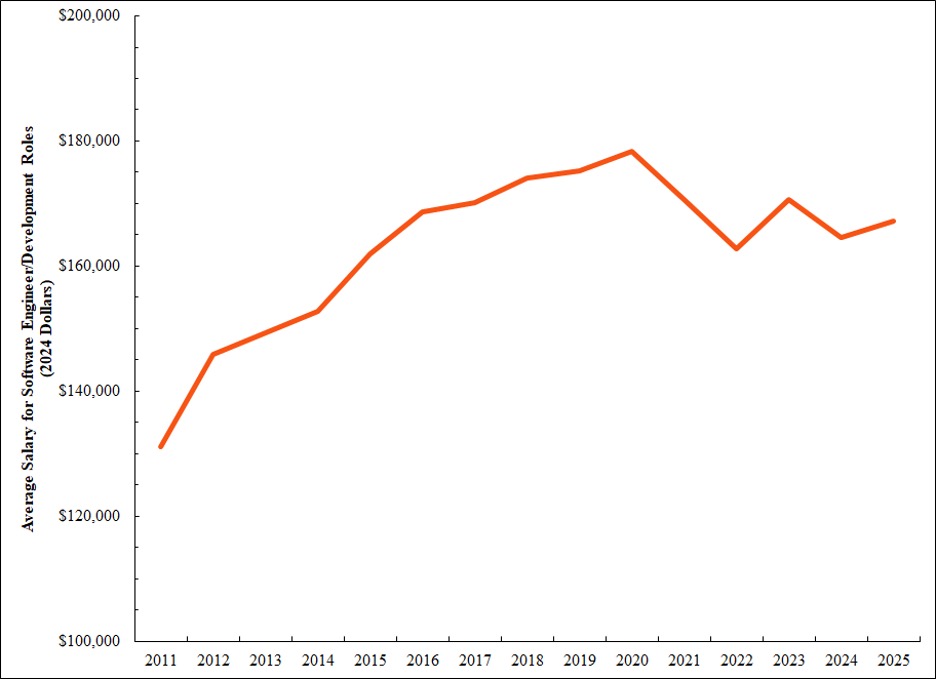

Microsoft-specific wage data were not easily accessible. The Economist reported that the median pay for software developers at “tech giants including Alphabet, Microsoft and, until recently, Meta” was close to $300,000. Lucky for us, however, Microsoft sponsors thousands of H-1B visas, which provides a source of publicly available salary data. Using these data, we can get a sense of the trend in how Microsoft software engineer compensation has evolved over time. Because they are beholden to their American employer, H-1B visa-holders likely earn wages below their American counterparts. Nevertheless, the trajectory of wages of H-1B workers should roughly track the trajectory of wages of their American peers.

Figure 3: H-1B Data Suggest That Microsoft Software Engineers’ Real Wage Stagnated in the 2020s

Source: Data is from H1B Grader.com which states that “salaries data is extracted from the H1B Labor Condition Applications (LCAs) filed with the US Department of Labor by [the] Microsoft Corporation.”Notes: We combined various positions’ pay information to produce this average salary measure. Positions that were consolidated had titles that indicated they were roles in software engineering or development. We explicitly excluded IT-specific roles.

While H-1B software engineers working at Microsoft saw real wage increases during the 2010s, by the 2020s, real wages appear to have stagnated. This trajectory likely reflects the trend for all Microsoft developers, including domestic workers.

While these figures are by no means perfect, if workers truly reaped benefits from their AI-boosted productivity in a significant way, the above charts should have reflected such an outcome. Unfortunately, from what we can see, wages have not captured much of AI’s productivity impact. This lends credence to the hypothesis of monopsony exploitation restraining wage growth—in other words, Microsoft (the employer) is appropriating the productivity gains of its workers, presumably because the workers do not have credible outside employment options to which they could turn easily in response to a wage cut.

Software Developers Face an Uncertain Future

Unfortunately, not only do software developers not receive boosts in their compensation commensurate with their productivity increases, but many also now risk losing their jobs. As noted above, Microsoft has shed 36,000 jobs since 2023.

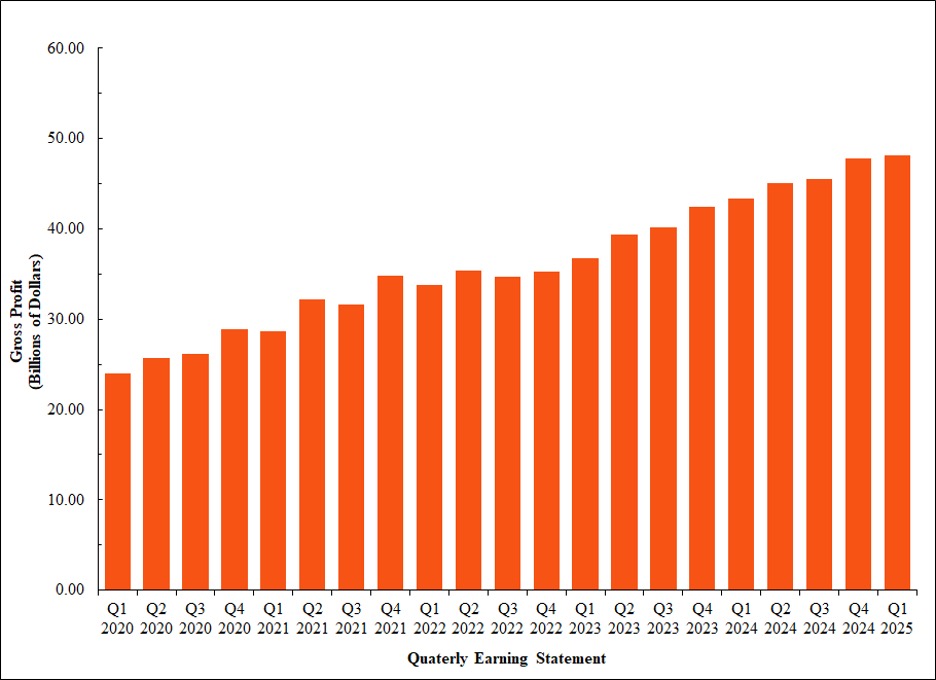

The cause of these mass layoffs does not appear to lie with any underperformance on Microsoft’s part. On the contrary, Microsoft’s gross profits have continued to rise over the past few years, as seen in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Microsoft Has Seen Significant Profit Growth in the Past Five Years

Source: MacroTrends.net.

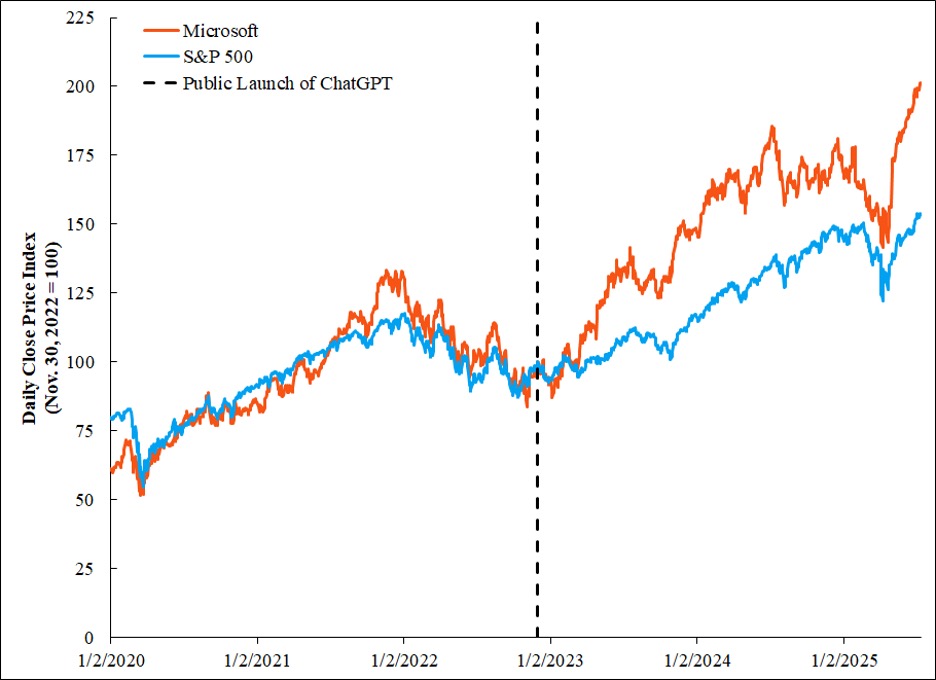

Microsoft stock has also performed tremendously since the release of ChatGPT. If anyone is benefiting from the increased productivity of its workers, it appears it is Microsoft itself. (To be fair, given that Big Tech workers’ compensation packages often include stock, they too benefit from the AI rally even if the compensation figures reviewed above may not reflect such increases.) The combination of layoffs and no real impact on pay appears to at least suggest that AI will function as a substitute, rather than a complement, to human labor.

Figure 5: Microsoft Stock Has Performed Well in the Age of AI

Source: Data retrieved using getsymbols package in Stata, sourced from Yahoo! Finance. Notes: As is standard, we used the adjusted closing stock price. Data is from Jan. 2, 2020 to July 11, 2025. Closing price indexed such that November 30, 2022 equals 100 (notable for being the date OpenAI first publicly released a demo of ChatGPT, which would go on to reach a million users in less than a week).

AI Fits a Trend of Growing Productivity and Wage Stagnation

Whether AI will truly revolutionize the workplace and make many human workers “go the way of the horses” remains to be seen. From what we have analyzed, however, even if AI does not replace human labor, workers should not put too much hope that they will reap the rewards of their increased productivity. AI continues a trend that started back in the 1980s: the divergence between worker’s productivity growth and their wages. Without a significant policy intervention in labor markets, such as a federal job guarantee or unionization to countervail monopsony power, AI may be a technology that continues to exacerbate the inequality of the 21st century.