On December 3, 2024, Chris Salinas officially entered a nightmare that would make Freddy Krueger proud—a nightmare in the medical industry known as prior authorization. Even I, as his gastroenterologist, didn’t know at the time that this one would become my biggest nightmare yet. Chris has given me permission to share the details of his experience, including his medical ailments.

Chris has ulcerative colitis, a chronic autoimmune disease of the colon that can cause flares of bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fatigue, among many other symptoms. I have been treating Chris and his ulcerative colitis for over 15 years. Over those years, for various reasons, he had ultimately failed multiple medications for his illness. By December of last year, the next one we wanted to try was Entyvio, a drug under patent approved by the FDA for ulcerative colitis in 2014. Entyvio is considered in the industry a “specialty pharmacy” drug. In theory, nobody in the industry knows exactly what that means. In practice, what it means is big money, the money that pays for all those ads you see on TV for Ozempic, Wegovy, Skyrizi, and the like (rule of thumb: if the brand has a “z” or “v” or “y” in the name, it’s likely a moneymaking specialty drug). And in practice, what it meant for Chris and me is that I needed to get prior authorization for approval of Entyvio.

Just the phrase “prior authorization” sends a chill down every physician’s spine. On its face, prior authorization has a functional purpose: to control utilizing drugs that can be quite costly for a health plan to cover. Yet imagine your worst call climbing up the giant sequoia of customer service phone-trees. A call for a prior authorization is worse.

You think I’m exaggerating? Every year the American Medical Association conducts a nationwide survey of a 1,000 practicing physicians on prior authorization. In 2024, 40 percent of physicians had staff who worked exclusively on prior authorizations and spent 13 hours weekly on them; 75 percent reported that denials of prior authorizations had increased; 80 percent didn’t always appeal the denials, due to past failures or time constraints. And almost 90 percent of physicians reported burning out from the process. I know physicians who closed down their practices and retired early solely because of prior authorization.

According to the survey, the impact on patient care is no less nightmarish. Nearly 100 percent of physicians felt that prior authorization negatively affected patient outcomes; 23 percent noted that it led to a patient’s hospitalization; 18 percent said it led to a life-threatening event; and 8 percent said it led to permanent dysfunction or death. Fortunately, Chris wasn’t at death’s door. But even with a philosophical approach that most of the time in medicine, less is more, I felt that getting on Entyvio was Chris’s best shot at improving his quality of life, free of the extended flare of ulcerative colitis he was enduring.

So last December, I called Express Scripts, Inc. (“ESI”) to get the prior authorization for Entyvio. ESI is the pharmacy benefit manager (“PBM”) of Chris’s employer-based health plan. For those who haven’t studied the FTC’s damning 2024 interim report on the industry (“FTC report”), PBMs serve as the middlemen between the pharmacies that dispense drugs, the manufacturers that make them, and the government/employers/insurance plans that pay for them. I gave ESI all the required clinical information for approval of both the initial intermittent intravenous infusions for the first six weeks and the subsequent biweekly maintenance injections Chris would be giving to himself subcutaneously. As Chris had by then failed multiple other therapies, it was a relatively easy call for ESI to grant the prior authorization for Entyvio. I then called in both the intravenous and subcutaneous Entyvio prescriptions to Accredo, the administering specialty pharmacy, who assured me that we were good to go.

We were not good to go. At first, Accredo told me that Chris could get the infusions at home through a service set up by Accredo. Then it told me it couldn’t. Then it told me it would find a local infusion center to administer the drug. Then it told me I had to find one. At every twist and turn, I had to initiate the call to Accredo to find out why the infusions hadn’t started. So did Chris, who said about his Accredo calls: “There were many circular conversations where it just went nowhere. Every time they would tell me, you have to give us a week and then call us back; and then when I call them back, it’s just like starting the process over again. And then again, and again, and again.”

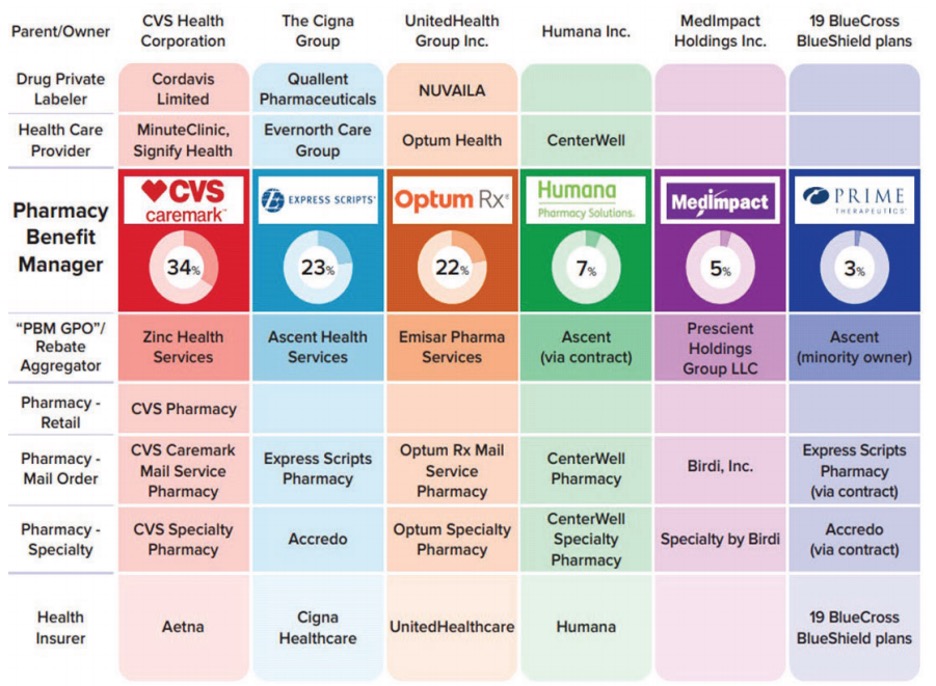

The breakdown in the prior authorization process that Chris and I were weathering is an endemic breakdown in healthcare quality. That breakdown in quality is the result of the incredible horizontal concentration and vertical integration the last few decades have wreaked in the healthcare industry. This chart from the same FTC report tells the tale.

ESI appears in the second column under The Cigna Group, as the associated PBM. The 23 percent below its name indicates that ESI controls 23 percent of all prescriptions filled in the United States.

On horizontal concentration overall, the three biggest PBMs—CVS Caremark, ESI, and Optum Rx, manage nearly 80 percent of all prescriptions filled in the United States; in terms of the standard Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) measurement of horizontal concentration, the mean HHIs were pushing 4,000 and climbing in state and local geographic markets.

On vertical integration, the three biggest PBMs are owned by the three of the five biggest health insurance companies in America—CVS Caremark under Aetna, ESI under Cigna, and Optum Rx under United. The vertical integration doesn’t stop there: the healthcare conglomerates that own the biggest PBMs also increasingly own private labelers that manufacture the drugs, the providers who prescribe them, and the pharmacies that dispense them. This includes Accredo, the specialty pharmacy owned by Cigna—which owns ESI, the PBM!

To any reasonable person thinking through the inevitable conflicts of interest, beware. Your head may eventually explode—for which you’ll probably need a prior authorization for something. The FTC report catalogs many of the adverse effects of horizontal concentration and vertical integration involving PBMs: (1) excluding generic drugs from formularies in exchange for higher pay-to-play “rebates” from the manufacturers; (2) recasting group purchasing organizations into rebate aggregators, often headquartered offshore, that still enjoy safe harbor from anti-kickback law; (3) steering patients exclusively to the conglomerates’ own PBMs and specialty pharmacies while crowding out independent pharmacies, especially when high-profit specialty drugs are involved; (4) turning contracts with independent pharmacies that have little bargaining position effectively into opaque adhesion contracts with “clawbacks” that make it possible for the pharmacies even to lose money, in the end, from a sale; and (5) abusing prior authorization and other utilization management tools to preference the conglomerates’ financial interests over the patients’ best interests.

The FTC report was criticized by a dissenting Commissioner (Holyoak) for being prematurely released without “rational, evidence-based research” to show that horizontal concentration and vertical integration of PBMs raised consumer prices. Accordingly, in 2025, the FTC expanded on its 2024 report, by analyzing additional data received from PBMs, to show that significant markups on numerous specialty generic drugs—some exceeding 1,000 percent—made PBMs and their affiliated specialty pharmacies huge revenues. That, it followed, cost government and commercial plan sponsors significantly more money, along with the subscribers/patients who shared the increasing costs.

Likely backroom political gamesmanship notwithstanding, the FTC should be praised and pushed to continue focusing on the effect of PBM consolidation on consumer drug prices. But with the focus on consumer prices, neither the 2024 interim report, nor its dissent, nor the 2025 update fully captures why horizontal concentration and vertical integration of PBMs are so bad for healthcare. Take it from an on-the-ground, practicing physician who has been at bedside, for over a quarter-century, observing policymakers afflicted with an evidence-enslaved (rather than evidence-informed) econometrics delirium rotting the core of what matters in healthcare.

It’s not just the price effects—it’s also the quality! Horizontal concentration and vertical integration of PBMs, and healthcare at large, are destroying quality in healthcare. Surely the FTC is aware of these non-price effects, as the over 1,200 public comments received by the FTC on PBMs’ business practices likely revealed. The 2023 Merger Guidelines published jointly by the FTC and the DOJ emphasized the same, adding a “T” to the end of the “SSNIP” of the Hypothetical Monopolist Test: “A SSNIPT may entail worsening terms along any dimension of competition, including price (SSNIP), but also other terms (broadly defined) such as quality, service, capacity investment, choice of product variety or features, or innovative effort.”

Yes, SSNIPTs may be harder to quantify than SSNIPs. But when it comes to PBMs, SSNIPTs galore smack you in the face.

Many phone calls later, and over a month after ESI had granted the prior authorization of Entyvio, Chris finally received his first of three infusions. It cost him around $300. He was then told the second infusion would cost him $1,800. That triggered another set of phone calls involving Accredo, with Chris noting, “They kept telling me that my insurance company denied [the Entyvio], and I said no, my insurance company did not deny it . . . I was actually getting ready to write an $1,800 check.” Fortunately, as Chris explained, the pharmacy and PBM then found the co-pay assistance program information Chris had sent, which they had apparently misplaced. The price of his second and third infusions? Five dollars each.

Chris’s ulcerative colitis symptoms responded well to the Entyvio infusions. But the healthcare nightmare wasn’t over. Chris was supposed to transition to the subcutaneous Entyvio shots in late April, eight weeks after his last infusion. When he called Accredo in March to confirm, he was told that Accredo didn’t have the prescription for the shots. I then called Accredo and was told the opposite. Chris then called and learned that Accredo had two accounts in his name, one of which was dormant (supposedly from the change of calendar year) and where the prescription was hiding. Accredo assured him that it would merge the accounts, and all would be good. Chris called again a couple of days later, when Accredo told him it was waiting on approval from his insurance company—even though the Entyvio had already been approved. More phone calls the following week, and the prescription was lost again because the accounts had not in fact been merged. Late April came and went, with no continuation of drug.

Chris estimates that between March and May, he made over 20 phone calls to Accredo. During the lapse in treatment, his cramps, diarrhea, and urgency returned. “In the meantime, I’m having to deal with my diagnosis . . . which is not fun, right? I’m having to kind of manage my travel that I do for work around that situation, which is difficult. And it’s a lot of stress . . . being on airplanes and all that kind of stuff.” It was a lot of stress for me as well, knowing that the longer Chris was off Entyvio, the more potential he would have to develop antibodies to the drug that would render it ineffective when resumed.

It all came to a head on May 21, a month after Chris was supposed to start the Entyvio shots. I spoke to Paul at Accredo, then Jeanine at ESI, then Mark, Jeanine’s supervisor, while I made Paul stay on the line. ESI informed me for the first time that a fax was allegedly sent to me on January 3 denying the prior authorization for the subcutaneous Entyvio. When asked whether it had sent the denial by regular mail, ESI said no. The reason for the denial? According to ESI, I had not answered some clinical criteria question—a question I had certainly answered when the infusions and injections were initially approved back in December. When I insisted on clearing up this nonsense once and for all over the phone, ESI informed me that a policy change beginning in 2025 had eliminated approvals over the phone; they could only be done via fax. The very tech that had failed us in communication of the purported denial. All this, with ESI, as a PBM in the business of administering healthcare, knowing full well the impact this was having on Chris’s health.

I finally demanded to speak to a peer, for a peer-to-peer review. In 2024 and 2025, that no longer means a gastroenterologist, or even a medical doctor, but often a nurse or pharmacist. No offense to nurses or pharmacists; they are sacred to healthcare. But when it comes to prior authorization for a specialty drug like Entyvio, they are not my peers. Nonetheless, the peer here was a pharmacist named Stefan—the first person at ESI I felt wasn’t carbon-based AI. He acknowledged the injustice of the situation but said my only recourse was to fax clinical information again to seek approval.

And then, magically out of the blue . . . Stefan said he found some “override” to approve the subcutaneous Entyvio. Just like that, a personal-record-breaking two hours and 45 minutes into the call, the prior authorization was over.

I give you all these gory details (believe it or not, with many left out) not to be melodramatic, but because when it comes to going through the prior authorization gauntlet with these highly concentrated, vertically integrated PBMs, this is now the norm, not the exception. As chronicled in the public comment by the American Economic Liberties Project, past lapses in enforcement by the FTC and DOJ created these consolidated beasts. And if you download the appendices of that comment, you will read one similarly abominable experience after another sampled from anti-PBM Facebook groups with names like “DOWN WITH Express Scripts and Accredo!”. On the Better Business Bureau website, ESI has a 1.03/5-star rating, with 1,555 complaints in the last three years. Other PBMs fare no better. In other words, horrible quality is a feature, not a bug, of the biggest PBMs and the healthcare conglomerates who own them—and own you, should you be dependent on them. In the words of former FTC chair Lina Khan, these PBMs have become “too big to care.”

Cory Doctorow says it best: “Enshittification is a choice.” He was talking about Google search. But he may as well have been talking about too-big-to-care healthcare. The lobbyist arm of the big insurance companies recently took notice of their “enshittification” and vowed to simplify prior authorization. But insurance companies have vowed that before, in 2018 and again in 2023.

I’m a GI doctor. I know good shit from bull. And now Chris does as well. I asked him how he would clean it up. “I have to go through [ESI and Accredo],” he lamented, “because of the plan that I’m on with my company, right? But if I had the choice because of customer service, I’d never deal with them again . . . I think that people aren’t looked at anymore as patients; they’re looked at as a business. There’s no personal side to it.”

Chris wants choice in healthcare. The only way he’ll get choice—and not the choice PBMs have made over and over again—is to break these behemoths up. Only then will these companies have skin in the game again and have to compete for customer loyalties. And only then will we renew the “care” in healthcare.

Venu Julapalli is a practicing gastroenterologist and recent graduate of the University of Houston Law Center.