Delta president Glen Hauenstein told investors in July that AI-based pricing is currently used on about 3 percent of its domestic network, and that the company aimed to expand AI pricing to 20 percent of its network by the end of the year. This is bad news for flyers, and given the particular way Delta is accessing the technology, is particularly bad for competition.

Airlines have been using “dynamic pricing” for decades, which entails setting fares based on common (as opposed to individualized) factors like demand, timing, real-time supply, and pricing by competitors. A spokesperson for Delta insists the new technology is merely “streamlining” its dynamic pricing model.

Personalized pricing, made possible via surveillance and AI, is distinct from dynamic pricing, in that the former allows a firm to condition pricing on the circumstances of the customer. Hence, two people shopping for airfares at the same time might see different prices based on things like travel purpose (business or leisure), income estimates, browsing behavior, ticket purchase history, website used, or type of device used.

To implement the new technology, Delta is working with Fetcherr, an Israeli-based GenAI pricing startup whose clients include other airlines like Virgin Atlantic and WestJet, to power the pricing changes. Alas, the three carriers share overlapping routes. From London, Virgin Atlantic flies to several U.S. destinations, including Atlanta, Boston, Miami, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, New York, Orlando, and Washington D.C. Delta also operates flights from London to many of those same U.S. cities, including Atlanta, Boston, Los Angeles, and New York. WestJet has expanded its network into the United States, including to such destinations as Anchorage, Atlanta Minneapolis, Raleigh, and Salt Lake City. (Some of these routes are in partnership with Delta.) Economists and antitrust authorities recognize that there could be anticompetitive effects if common pricing algorithms lead to collusion. Check out the DOJ’s antitrust case against RealPage, in which landlords are alleged to have to turned over their pricing decisions to a common algorithm (RealPage).

During the company’s second-quarter earnings, Delta CEO Ed Bastian noted “While we’re still in the test phase, results are encouraging.” Hauenstein called the AI a “super analyst” and results have been “amazingly favorable unit revenues.” These boasts, aimed at investors as opposed to consumers, mean that AI-based pricing is raising profits—else the results would be ambiguous or discouraging. And those extra profits are likely coming off the backs of consumers. And as we will soon see, rising unit revenues means that AI-based pricing is not leading to price reductions on average, contra the predictions of price-discrimination defenders.

Price Discrimination Is Bad for Consumers, Even When Implemented Unilaterally

Economic textbooks are filled with passages claiming that the welfare effects of price discrimination are ambiguous. It’s worth revisiting the key assumption that permits such an innocuous characterization—namely, an increase in output. As we will see shortly, this assumption isn’t easily satisfied in the airline industry.

Consumer welfare or “surplus” is recognized as the area underneath the demand curve bounded from below by the price. For a particular customer, surplus is the difference between her willingness to pay (WTP) and the price. Importantly, when it comes to first-degree price discrimination—charging each consumer her WTP—all consumer surplus is transferred to the producer, meaning consumers receive no benefit from the transaction beyond the good itself.

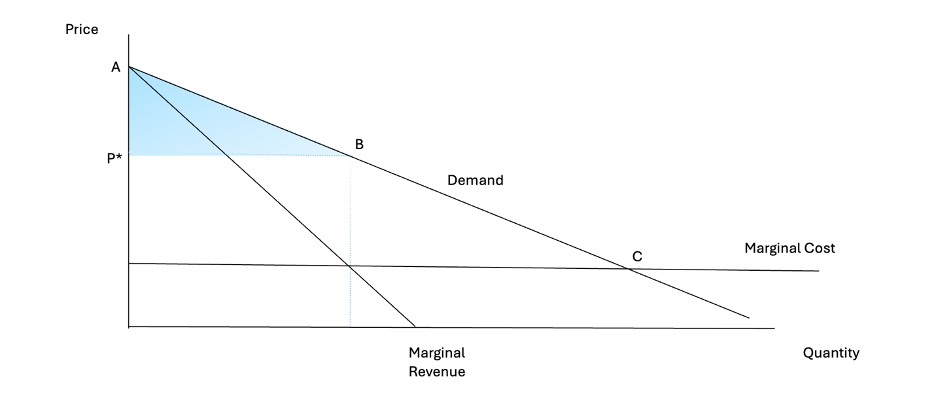

Let’s start with the basics. The figure below shows what happens when a firm facing a downward-sloping demand—an indicator of market power—is constrained to charging a single, uniform price to all comers. The profit-maximizing uniform price, P*, is found at the intersection of the marginal revenue and marginal cost curve, and then looking up to the demand curve to find the corresponding price.

Even at the profit-maximizing uniform price, P*, the firm with market power leaves some consumer surplus on the table, equal to the area of the triangle, ABP*. This failure to extract all consumer surplus motivates many anticompetitive restraints that we observe in the real world, such as bundled loyalty discounts. Another way to extract that surplus is, if possible, to charge each consumer along the demand curve between A and B her WTP. And that’s where AI-based personalized pricing comes in. Consumers along that portion of the demand curve are clearly worse off relative to a uniform pricing standard. The only consumer who is indifferent between the two regimes is the one whose WTP is just equal to P*, situated at point B of the demand curve.

Defenders of price discrimination are quick to point out that the price-discriminating firm can reduce its price, relative to P*, to customers on the demand curve from B to C, bringing fresh consumers into the market (who were previously priced out at P*) and expanding output. After all, they claim, there is incremental profit to be had there, equal to the difference between the WTP (of admittedly low-value consumers) and the firm’s marginal cost. There are at least two practical problems, however, with this theoretical argument as applied to airlines.

First, this argument presumes that airline capacity can be easily expanded. But an airline can only enhance output in a handful of costly ways. An airline can add more planes, which are not cheap, or more seats per plane, decreasing the quality of the experience for all passengers. An airline could also add more flights per day, but this too is costly because the airline must secure permissions from the airport at the gates.

Second, as noted above, the customers between B and C along the demand curve are the low-valuation types, who are not coveted by legacy carriers like Delta or United. These low-valuation and budget-conscious customers tend to fly (if at all) on the low-cost carriers and ultra-low-cost carriers like Southwest and Spirit, respectively. Serving these customers, as opposed to extracting greater surplus from high-valuation customers, is likely less attractive to Delta, especially if doing so would compromise the quality of existing customers (through, for example, cramming more seats on a plane), or would put downward pressure on prices of other items that are sold on a uniform basis (e.g., in-flight WiFi or alcoholic drinks).

Even if you don’t accept these practical arguments, it bears repeating once more that under first-degree price discrimination, there is no consumer surplus, even at the expanded output. So expanded output here is nothing to cheer about, unless you are an investor in the airlines or work as an airline lobbyist or consultant. And if there’s any doubt on the price effects from AI-based pricing, recall the boast from Delta’s executive—unit revenues are rising, which can’t happen if Delta is using the technology to drop prices on average to customers.

Price Discrimination Is Even Worse for Consumers When Implemented Jointly with Rivals

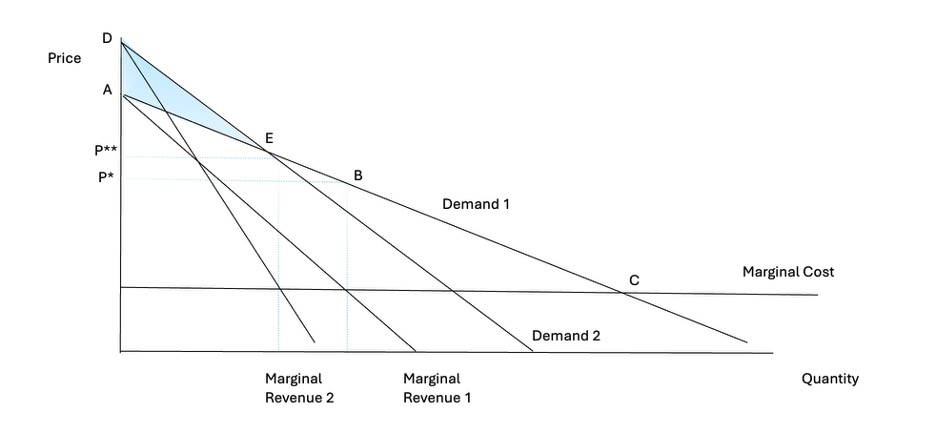

If this weren’t bad enough, there’s a knock-on effect from AI-based personalized pricing, especially if the technology vendor is also supplying the same pricing assistance to Delta’s rivals. Recall that Delta uses a pricing consultant that is also advising airlines with overlapping routes with Delta. In that case, the common pricing algorithm can facilitate collusion that would other not be possible. We can return to our figure to see how collusion can make consumers even worse off relative to discriminatory pricing.

Relative the original demand curve (Demand 1), the demand when prices are set via a common pricing algorithm (Demand 2) is less elastic, meaning that an increase in price does not generate as large a reduction in quantity. In lay terms, the demand is steeper. This rotation of the demand curve, made possible by weakening an outside substitute via collusion, causes the uniform profit maximizing price to rise above P* to P**. And this higher price opens the possibility of additional surplus extraction via price discrimination, equal to the area DAE, for the highest-value customers.

Where We Do Go from Here?

At this point, we have two different policy choices. The first is to pursue an antitrust case against Delta and Fetcherr. The problem with antitrust—and I make this argument against my own economic interests as an antitrust economist—is that such a case against Delta would not be resolved for years. The DOJ’s case against RealPage was filed nearly a year ago (August 2024), and we’ve seen little progress. In complex litigation, the defendants need time to produce voluminous data and records in response to subpoenas, the plaintiffs’ economists will have to understand those data and build econometric models that will be subjected to massive scrutiny by even more economists, there will be hearings, motions for summary judgment and to exclude testimony, and then a trial.

The second intervention is to ban, via regulation at either the city or federal level, the use of common pricing algorithms for airlines or more broadly. Similar bans have been imposed by cities against RealPage and Airbnb, which also has been accused of employing a common algorithm (and the subject of a forthcoming piece). Senators Ruben Gallego of Arizona, Mark Warner of Virginia, and Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut sent a letter to Delta on July 22 correctly asserting the harms from Delta’s AI-based pricing, which will “likely mean fare price increases up to each individual consumer’s personal ‘pain point’ at a time when American families are already struggling with rising costs.” A senate hearing could be in order. But Delta won’t back off from this approach unless and until it perceives the threat of regulation to be credible.

Of the two options, I prefer the latter. With luck, Congress will too!

Many in the anti-monopoly movement are celebrating the recent DOJ victory against the Northeast Alliance (NEA). It’s a rare enforcement action in the airline industry, and a rare decision that gives a clear victory to the DOJ.

But I will not be celebrating. What follows is my attempt to read the potential tea leaves from the NEA decision in looking forward to the JetBlue/Spirit merger. The TLDR: Don’t count the JetBlue/Spirit merger down and out based upon the NEA decision. While I’m pleased with DOJ’s victory, one step forward does not eradicate the giant leaps backward that have befallen the airline industry in the past few decades.

Fake Remedies and Abdication of Responsibility

In every instance of past consolidation in the airline industry, the DOJ (a) did nothing; (b) compelled the divestiture of slots and gates; or (c) filed a complaint, then got spanked by politicians into settling for slots and gates.

A couple of examples should suffice.

In 2013, the DOJ entered into a consent decree in the proposed merger of U.S. Air and American Airlines. The remedy, as is often the case, focused on the sale of slots and gates at LaGuardia Airport, as well as gates at other airports.

Yet the complaint stated that competition would have been enhanced with the emergence from bankruptcy of American Airlines as a standalone competitor. The complaint also argued that the industry had suffered from consolidation (from nine to five majors), and that fares increased due to that consolidation.

So, it’s only natural that slots and gates at a few airports would fix that, right? Not according to the complaint. Head-to-head competition would be eradicated. And it’s hard to start a network carrier, I might add, even with access to slots and gates.

One other example is in order. In the United-Continental merger, despite 18 overlapping markets (routes), the DOJ closed the investigation into the merger with the parties’ agreeing to sell slots and other assets in Newark to Southwest Airlines.

Slots and gates solve all ills in the airline industry. Got it. Unless you’re in one of those overlapping markets, where there is no obligation of the winning bidder of said slot to service the same route. Or unless you’re in rural America, where service has either disappeared completely or is much more expensive.

I don’t want to rehash the entire history of consolidation in the airline industry or the significant role that DOJ has played in shaping that development, but these two transactions are just a few on the path of placating the airlines by essentially creating a “tax” on the transaction that did not cure the anticompetitive ills of the mergers whatsoever. I do not, by the way, blame my former colleagues on staff at the DOJ for this. My blame goes higher up than the trial attorneys and paralegals who work those cases.

Given these data points, does the decision by Judge Sorokin represents a “sea change” in antitrust enforcement in the airline industry? I think not. Let’s break the decision down by some key elements: Concentration, efficiencies, and entry. I’ll also add a comment about the role of economists in that analysis.

Concentration Is Not New

Judge Sorokin discovered what many of us know already: “The industry is highly concentrated. Four carriers control more than eighty percent of the market for domestic air travel: the three GNCs (American, Delta, and United) and Southwest. The remainder of the market—less than twenty percent—is generally split among nine smaller carriers.”

At mainstream antitrust conferences, where consultants are rewarded for taking positions aligned with the most powerful, one might find a variety of people telling you that the airline industry is not concentrated. Since 2001, American bought TWA, U.S. Airways bought America West, American merged with U.S. Air, Delta with Northwest, United with Continental, and Southwest with AirTran. The full list can be found here. In each instance, DOJ was complicit. And, by the way, the market was highly concentrated before those decisions. Take DOJ’s complaint in U.S Air/American: “In 2005, there were nine major airlines. If this merger were approved, there would be only four. The three remaining legacy airlines and Southwest would account for over 80% of the domestic scheduled passenger service market, with the new American becoming the biggest airline in the world.” Indeed, many of the HHIs in the markets in question in that merger exceeded 2,500, or what the Merger Guidelines consider to be “highly concentrated markets.”

After that merger, others followed. Alaska and Virgin merged, Southwest bought some locals, and United bought ExpressJet.

So it is only natural that the DOJ allege concentrated markets in its complaint in the JetBlue/Spirit Merger: According to the agency’s calculations, the merger increases concentration in 150 routes, including 40 nonstop routes. The complaint alleges the risk of heightened coordination among the remaining airlines as well and lower innovation in service.

In short, there is nothing new on the concentration side. ‘Twas ever thus (at least the past 20 years). This suggests that high concentration is not predictive of stopping an anticompetitive merger.

Efficiencies Arising from the Elimination of Competition

Judge Sorokin was skeptical of the claimed efficiencies in the NEA: “American’s Chief Executive Officer (‘CEO’) described the numerous challenges created by mergers, as well as the “inordinate amount of management time and attention” required to integrate two airlines.” Prior mergers touted those great efficiencies. Some during that time period (me included) argued that those efficiencies do not pan out, take longer to achieve, and may be ethereal.

But the parties to the NEA claimed efficiencies even absent merger. Judge Sorokin rejected the claimed efficiencies, ruling they were insufficient to rebut the claimed harms in the NEA litigation. As Judge Sorokin pointed out: “These features arise only if the defendants mimic one carrier, elect not to compete with one another, and cooperate in ways that horizontal competitors normally would not. This elimination of competition negatively impacts the number and diversity of choices available to consumers in the northeast. As such, ‘benefits’ arising in this way cannot justify the defendants’ collusion.”

It’s hard to read that conclusion without thinking about the claims of merger efficiencies in the past. It suggests that the efficiency claim would have been stronger if the NEA members had merged rather than formed an alliance. If that’s the right reading, that could spell trouble for the DOJ in JetBlue/Spirit.

So again, nothing new here, except it was defendants arguing that merger efficiencies are hard to achieve, and in essence claimed that the NEA achieved the same efficiencies without requiring integration. Again, the U.S. Air/American complaint was skeptical of such purported efficiencies: “There are not sufficient acquisition-specific and cognizable efficiencies that would be passed through to U.S. consumers to rebut the presumption that competition and consumers would likely be harmed by this merger.”

Often times, those statements are made in hopes of “out of market” efficiencies counting in favor of the transaction. As the Commentary to the Merger Guidelines states, “Inextricably linked out-of-market efficiencies, however, can cause the Agencies, in their discretion, not to challenge mergers that would be challenged absent the efficiencies. This circumstance may arise, for example, if a merger presents large procompetitive benefits in a large market and a small anticompetitive problem in another, smaller market.” While that Commentary goes against everything that Philadelphia National Bank stands for, it is nonetheless continued policy. Just ignore the citation to Philadelphia National Bank in the complaint. That’s on presumptions.

Nonetheless, the complaint in Jet Blue/Spirit states that “Defendants have not yet described any procompetitive efficiencies in the alleged relevant markets.”

The American Antitrust Institute has been shouting this point for at least a decade. Take Diana Moss’s paper in 2013, explaining that: “System integration (e.g., integrating reservation and IT systems and combining workforces) in some past mergers has been difficult, protracted, and more costly than what was predicted by the airlines.” Others, including yours truly, have asserted the same.

Entry Is Not Easy

Judge Sorokin indicates that barriers to entry into the markets where NEA operates are significant, with likely entry not mitigating the anticompetitive effects. For example, in Boston and New York City, the judge describes the entry barriers as insurmountable: “By ending competition between American and JetBlue, the NEA means that seventy-three percent of domestic flights at Logan are controlled by two (rather than three) entities: Delta and the NEA. In New York, where entry or expansion by any airline is severely limited due to the FAA’s slot constraints at JFK and LaGuardia, the NEA ensures that eighty-four percent of the slots at JFK and LaGuardia are held by the same two (rather than three) entities that now dominate Logan.”

The JetBlue/Spirit complaint concurs: “New entrants into airline markets face significant barriers, including: difficulty in obtaining access to airport facilities or landing rights, particularly at congested airports; existing loyalty to particular airlines; and the risk of aggressive responses to new entry by a dominant incumbent.”

Curious. If entry is as difficult as the current DOJ and Judge Sorokin now suggest, where were those concerns in the prior two decades, when gate and slot sales were held out as the great elixir to lost actual competition?

Not All Economists

Judge Sorokin found defendant economists’ testimony problematic, lacking in nuance, and biased: “The apparent bias of the defendants’ retained experts is reason enough to reject the

opinions and conclusions they rendered in this case.” Again, this is not a surprise. Matt Stoller’s description of people in lab coats who never get graded on their assignments is apt.

Much has been written about the repeated use of economists to weave magical models that later result in unhappiness for consumers. ProPublica had a piece on the expert economist market four years ago, titled “These Professors Make More Than A Thousand Bucks an Hour Peddling Mega Mergers.” The title is a bit dated, due to the inflationary effects in the economic expert market—$1,000 is considered affordable now. Regardless, this practice is ages old. Agencies almost expect certain economists to walk in the door peddling particular mergers. I should disclose my own personal experience getting stomped by Dan Rubinfeld as I sought to stop the United/Continental merger. Consolidation in 18 nonstop markets was simply insufficient to be a problem for defendants’ economist, who was far more prepared, diligent, and careful.

I do not take Judge Sorokin’s judgment of defendants’ economists as a judgment of all experts. I take it to mean that economists must do more to shore up their assertions and conclusions apart from merely proclaiming themselves to be gods of knowledge. In other words, experts should not engage in “sweeping assertions,” “unnuanced and poorly reasoned conclusions,” “overly simplistic view[s],” “absurd” reasoning, or other analysis the court finds is entitled to ultimately “no weight.”

In short, maybe courts will start treating defendant’s economic experts like they treat plaintiff’s economic experts. And yes, that means they’ll get the blame for losing, even if it not deserved. It might also mean that JetBlue/Spirit should think about its expert reports carefully, and who gives those reports.

Conclusion

Before I get emails pointing out that policies and administrations change: I know. But those policies have an effect on the law as it is applied. Just as one example, there is no meaningful or substantive judicial review of consent decrees. And thus, when the DOJ became the Surface Transportation Board of the friendly skies (blessing all mergers that came before it), there was no countervailing power to stop it. Those impacts cannot be undone. They are permanent.

So, while I’m happy about Judge Sorokin’s decision, it doesn’t predict the future. The DOJ may very well still lose JetBlue/Spirit if it goes to trial. And if does lose, it only has its prior self to blame.