My musings on Twitter are mostly a stream of poking fun of corporatist takes in The New York Times or The Economist. Every once in a while, for reasons that are impossible to understand, a tweet takes off, like this one, which mocked a far-fetched inflation theory propagated in a guest essay for the Times on July 8.

Under this theory, elevators and the elevator union are to blame for the housing affordability crisis. The most charitable interpretation, which the title of the piece nearly rules out, is that the high cost of elevators are emblematic of other supply problems exacerbated by onerous regulations. The tweet was retweeted over one thousand times. It seems that the progressive community took umbrage at the Times for breathing life into a YIMBY story that deflected attention away from the powerful companies actually setting rents and towards (largely powerless) elevator workers.

Some of the quote tweets were supportive, and some were not so kind. Matt Yglesias called me a “leftist professor” who “just resorts to bullying” his opponents, and even intimated that I was insensitive to the plight of the disabled community. (Perhaps he was miffed at a prior column.) Of course, the disabled care about access to elevators, but my tweet spoke to the price of housing, and profit-maximizing landlords should not, as a matter of economic theory, factor the fixed cost of elevators into their pricing decisions.

It would be nice for the Times to give some attention to an alternative and more plausible hypothesis behind the housing affordability crisis—namely, that hedge funds and private equity firms have been buying up properties that would otherwise go to households, creating an artificial scarcity in real estate markets, and thereby driving up rents. Matt Darling, who sports a globe emoji in his Twitter handle but is otherwise a decent fellow, questioned whether this alternative hypothesis was serious: “It seems unlikely to be a driving force – there are 146,375,000 houses in the United States. I’d be surprised if private equity buying ‘hundreds of thousands’ is a major contributor.” I promised him I would look into the matter. Here is what I found.

Investors Have Been Busy Gobbling Up Homes

In the first three months of 2024, investors bought 14.8 percent of homes sold according to Realtor.com. In some cities, such as Springfield, Kansas City, and St. Louis Missouri, investors purchased around one in five homes. Investor-owned homes hit their peak in December 2022, accounting for 28.7 percent of all home sales in America. Per MetLife Investment Management, institutional investors may control 40 percent of U.S. single-family rental homes by 2030.

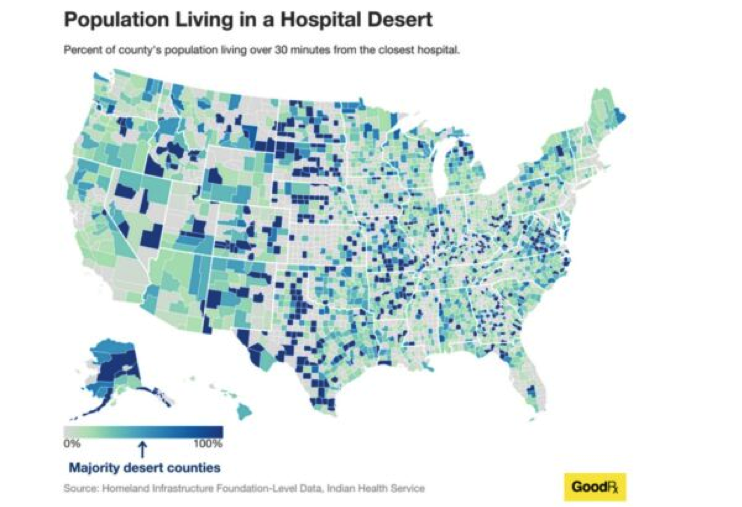

Robert Reich posted a wonderful video to Twitter explaining how Wall Street investors could be driving up rents. He explains that home ownership—the primary vehicle for accumulating wealth—is out of reach for many Americans. Investors are not randomly making home purchases across the country, as Darling’s question above presumes, but instead are targeting bigger cities and neighborhoods that are homes to communities of color in particular. In one neighborhood in Charlotte, North Carolina, Wall Street investors bought half the homes that sold in 2021 and 2022.

Such clustering of properties is occurring in several U.S. cities. A report from Drexel’s Nowak Metro Finance Lab found that between 2020 and 2021, 19.3 percent of sales of single-family homes in Richmond, Virginia, went to investors. It found that investors bought nearly a quarter of the homes in Jacksonville, Florida in the same period.

But Are These Investments Enough to Raise Housing Prices?

Economists have recently begun to explore the relationship between institutional investment and home and rental prices.

- Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2020) found that purchases by institutional investors, as measured by the share of properties owned by all institutional investors collectively in a Metropolitan Statistical Area, increase (1) the price-to-income ratio, especially in the bottom price-tier, the entry point for first-time buyers, and (2) the rent-to-income ratio generally, especially where the housing supply elasticity is high. By treating all institutional investors in the aggregate and thus as if it were owned a single entity, however, the St. Louis Fed study may have overlooked the incremental explanatory power of clustering properties by a single institutional owner in a given neighborhood.

- Watson and Ziv (2021) analyze the relationship between ownership concentration and rents in New York City, finding that a ten percent increase in concentration is correlated with a one percent increase in rents.

- Using a database comprised of all multifamily real estate transactions of greater than $2 million, Tapp and Peiser (2022) estimated the distribution of Herfindahl-Hirschman Indices across all Opportunity Zones within the United States, showing that investors have grown to consolidate a growing share of the affordable rental housing market.

- Linger, Singer and Tatos (2022) used a property tax data from the Florida Department of Revenue to calculate the individual market shares for owners of rental properties based on the number of units owned. For each Census Tract in the state, they calculate the consolidation of properties from 2015 through 2022, and then test whether such consolidation explains increases in rental prices or increases in rental inflation or both, controlling for other factors that might confound the concentration-inflation relationship. They find statistically and economically significant effects in both relationships.

- Using mergers of private-equity backed firms to isolate quasi-exogenous variation in concentration of ownership at the neighborhood level, Austin (2022) found that shocks to institutional ownership cause higher prices and rents.

- Coven (2023) estimated a demand system to study the effects of institutional investors’ conversion of large fractions of owner-occupied housing into rentals in the suburbs of U.S. cities. He finds that institutional investors decreased the housing available for owner-occupancy by 30 percent of the homes they converted, and their demand shock raised the price of housing purchased. He also found such behavior made it easier for renters to access neighborhoods that previously had few rentals.

A seminal lesson in industrial organization is that price coordination is easier, all things equal, when markets are concentrated. Indeed, merger enforcement is partially motivated by the prospect of coordinated pricing effects that flow a merger. So it shouldn’t surprise to anyone that, as institutional investors buy up the available stock of housing in a local market, housing prices rise.

An interesting development that might diminish the impact of clustering properties in a given neighborhood under a single roof, however, is the widespread adoption of pricing algorithms by third-party information aggregators. In March 2024, the Department of Justice opened a criminal investigation of RealPage, a top developer of property-pricing software. A class of renters as well as attorneys general from Washington, D.C. and Arizona brought lawsuits against the beleaguered software company. To the extent monopoly pricing can be achieved even by atomistic property owners via outsourcing the pricing decision to a third party, it might not be necessary to consolidate properties to exercise pricing power.

Policy Implications

In several European countries, such as Spain, Portugal and Greece, foreign investors were encouraged to buy property in exchange for a pathway to citizenship. The programs resulted in a flood of investment and speculation, causing rents to rise above what could be afforded by residents. The incentive plans have since been paired back, with countries hoping to re-direct investment into undeveloped pockets outside of the major cities.

The rather obvious economic lesson is that governments have an obligation to their voters, and free-market forces should not be allowed to price local residents out of their own neighborhoods. The same insight could be applied to domestic speculators in the United States.

In December 2023, Senator Merkley (D-Oregon) introduced the End Hedge Fund Control of American Homes Act, which would force large corporate owners to divest from their current holdings of single-family homes over ten years. Entities that fail to divest homes they own in excess of a 50-home cap would be taxed $50,000 for each excess home. And hedge funds would pay that fine if they own any homes at all after ten years.

Limiting the home ownership of hedge funds and other institutional investors makes economic sense, particularly in concentrated local real estate markets. Government funding of new housing projects also could address the imbalance between private supply and demand. Although it is generally unpopular among neoliberal economists and could weaken incentives to make further investments, capping rental inflation at five percent per year, as intimated by President Biden in this week’s NATO press conference, could also spell relief for renters. And pursuing common pricing algorithms under the antitrust laws could restore renters to the place they would have been absent the alleged price-fixing conspiracy, albeit with a significant lag, given the slow pace of antitrust.

All of these ideas are superior to focusing our energies on elevators. If only we could get the Times to listen.

The Justice Department’s pending antitrust case against Google, in which the search giant is accused of illegally monopolizing the market for online search and related advertising, revealed the nature and extent of a revenue sharing agreement (“RSA”) between Google and Apple. Pursuant to the RSA, Apple gets 36 percent of advertising revenue from Google searches by Apple users—a figure that reached $20 billion in 2022. The RSA has not been investigated in the EU. This essay briefly recaps the EU law on remedies and explains why choice screens, the EU’s preferred approach, are the wrong remedy focused on the wrong problem. Restoring effective competition in search and related advertising requires (1) the dissolution of the RSA, (2) the fostering of suppressed publishers and independent advertisers, and (3) the use of an access remedy for competing search-engine-results providers.

EU Law on Remedies

EU law requires remedies to “bring infringements and their effects to an end.” In Commercial Solvents, the Commission power was held to “include an order to do certain acts or provide certain advantages which have been wrongfully withheld.”

The Commission team that dealt with the Microsoft case noted that a risk with righting a prohibition of the infringement was that “[i]n many cases, especially in network industries, the infringer could continue to reap the benefits of a past violation to the detriment of consumers. This is what remedies are intended to avoid.” An effective remedy puts the competitive position back as it was before the harm occurred, which requires three elements. First, the abusive conduct must be prohibited. Second, the harmful consequences must be eliminated. For example, in Lithuanian Railways, the railway tracks that had been taken away were required to be restored, restoring the pre-conduct competitive position. Third, the remedy must prevent repetition of the same conduct or conduct having an “equivalent effect.” The two main remedies are divestiture and prohibition orders.

The RSA Is Both a Horizontal and a Vertical Arrangement

In the 2017 Google Search (Shopping) case, Google was found to have abused its dominant position in search. In the DOJ’s pending search case, Google is also accused of monopolizing the market for search. In addition to revealing the contours of the RSA, the case revealed a broader coordination between Google and Apple. For example, discovery revealed there are monthly CEO-to-CEO meetings where the “vision is that we work as if we are one company.” Thus, the RSA serves as much more than a “default” setting—it is effectively an agreement not to compete.

Under the RSA, Apple gets a substantial cut of the revenue from searches by Apple users. Apple is paid to promote Google Search, with the payment funded by income generated from the sale of ads to Apple’s wealthy user base. That user base has higher disposable income than Android users, which makes it highly attractive to those advertising and selling products. Ads to Apple users are thought to generate 50 percent of ad spend but account for only 20 percent of all mobile users.

Compared to Apple’s other revenue sources, the scale of the payments made to Apple under the RSA is significant. It generates $20 billion in almost pure profit for Apple, which accounts for 15 to 20 percent of Apple’s net income. A payment this large and under this circumstance creates several incentives for Apple to cement Google’s dominance in search:

- Apple is incentivized to promote Google Search. This encompasses a form of product placement through which Apple is paid to promote and display Google’s search bar prominently on its products as the default. As promotion and display is itself a form of abuse, the treatment provides a discriminatory advantage to Google.

- Apple is incentivized to promote Google’s sales of search ads. To increase its own income, Apple has an incentive to ensure that Google Search ads are more successful than rival online ads in attracting advertisers. Because advertisers’ main concern is their return on their advertising spend, Google’s Search ads need to generate a higher return on advertising investment than rival online publishers.

- Apple is incentivized to introduce ad blockers. This is one of a series of interlocking steps in a staircase of abuses that block any player (other than Google) from using data derived from Apple users. Blocking the use of Apple user data by others increases the value of Google’s Search ads and Apple’s income from Apple’s high-end customers.

- Apple is incentivized to block third-party cookies and the advertising ID. This change was made in its Intelligent Tracking Prevention browser update in 2017 and in its App Tracking Transparency pop-up prompt update in 2020. Each step further limits the data available to competitors and drives ad revenue to Google search ads.

- Apple has a disincentive to build a competing search engine or allow other browsers on its devices to link to competing search engines or the Open Web. This is because the Open Web acts as a channel for advertising in competition with Google.

- Apple has a disincentive to invest in its browser engine (WebKit). This would allow users of the Open Web to see the latest videos and interesting formats for ads on websites. Apple sets the baseline for the web and underinvests in Safari to that end, preventing rival browsers such as Mozilla from installing its full Firefox Browser on Apple devices.

The RSA also gives Google an incentive to support Apple’s dominance in top end or “performance smartphones,” and to limit Android smartphone features, functions and prices in competition with Apple. In its Android Decision, the EU Commission found significant price differences between Google Android and iOS devices, while Google Search is the single largest source of traffic from iPhone users for over a decade.

Indeed, the Department of Justice pleadings in USA v. Apple show how Apple has sought to monopolize the market for performance smartphones via legal restrictions on app stores and by limiting technical interoperability between Apple’s system and others. The complaint lists Apple’s restrictions on messaging apps, smartwatches, and payments systems. However, it overlooks the restrictions on app stores from using Apple users’ data and how it sets the baseline for interoperating with the Open Web.

It is often thought that Apple is a devices business. On the contrary, the size of its RSA with Google means Apple’s business, in part, depends on income from advertising by Google using Apple’s user data. In reality, Apple is a data-harvesting business, and it has delegated the execution to Google’s ads system. Meanwhile, its own ads business is projected to rise to $13.7 billion by 2027. As such, the RSA deserves very close scrutiny in USA v. Apple, as it is an agreement between two companies operating in the same industry.

The Failures of Choice Screens

The EU Google (Search) abuse consisted in Google’s “positioning and display” of its own products over those of rivals on the results pages. Google’s underlying system is one that is optimized for promoting results by relevance to user query using a system based on Page Rank. It follows that promoting owned products over more relevant rivals requires work and effort. The Google Search Decision describes this abuse as being carried out by applying a relevance algorithm to determine ranking on the search engine results pages (“SERPs”). However, the algorithm did not apply to Google’s own products. As the figure below shows, Google’s SERP has over time filled up with own products and ads.

To remedy the abuse, the Decision compelled Google to adopt a “Choice Screen.” Yet this isn’t an obvious remedy to the impact on competitors that have been suppressed, out of sight and mind, for many years. The choice screen has a history in EU Commission decisions.

In 2009, the EU Commission identified the abuse Microsoft’s tying of its web browser to its Windows software. Other browsers were not shown to end users as alternatives. The basic lack of visibility of alternatives was the problem facing the end user and a choice screen was superficially attractive as a remedy, but it was not tested for efficacy. As Megan Grey observed in Tech Policy Press, “First, the Microsoft choice screen probably was irrelevant, given that no one noticed it was defunct for 14 months due to a software bug (Feb. 2011 through July 2012).” The Microsoft case is thus a very questionable precedent.

In its Google Android case, the European Commission found Google acted anticompetitively by tying Google Search and Google Chrome to other services and devices and required a choice screen presenting different options for browsers. It too has been shown to be ineffective. A CMA Report (2020) also identified failures in design choices and recognized that display and brand recognition are key factors to test for choice screen effectiveness.

Giving consumers a choice ought to be one of the most effective ways to remedy a reduction of choice. But a choice screen doesn’t provide choice of presentation and display of products in SERPs. Presentations are dependent on user interactions with pages. And Google’s knowledge of your search history, as well as your interactions with its products and pages, means it presents its pages in an attractive format. Google eventually changed the Choice Screen to reflect users top five choices by Member State. However, none of these factors related to the suppression of brands or competition, nor did it rectify the presentation and display’s effects on loss of variety and diversity in supply. Meanwhile, Google’s brand was enhanced from billions of user’s interactions with its products.

Moreover, choice screens have not prevented rival publishers, providers and content creators from being excluded from users’ view by a combination of Apple’s and Google’s actions. This has gone on for decades. Alternative channels for advertising by rival publishers are being squeezed out.

A Better Way Forward

As explained above, Apple helps Google target Apple users with ads and products in return for 36 percent of the ad revenue generated. Prohibiting that RSA would remove the parties’ incentives to reinforce each other’s market positions. Absent its share of Google search ads revenue, Apple may find reasons to build its own search engine or enhance its browser by investing in it in a way that would enable people to shop using the Open Web’s ad funded rivals. Apple may even advertise in competition with Google.

Next, courts should impose (and monitor) a mandatory access regime. Applied here, Google could be required to operate within its monopoly lane and run its relevance engine under public interest duties in “quarantine” on non-discriminatory terms. This proposal has been advanced by former White House advisor Tim Wu:

I guess the phrase I might use is quarantine, is you want to quarantine businesses, I guess, from others. And it’s less of a traditional antitrust kind of remedy, although it, obviously, in the ‘56 consent decree, which was out of an antitrust suit against AT&T, it can be a remedy. And the basic idea of it is, it’s explicitly distributional in its ideas. It wants more players in the ecosystem, in the economy. It’s almost like an ecosystem promoting a device, which is you say, okay, you know, you are the unquestioned master of this particular area of commerce. Maybe we’re talking about Amazon and it’s online shopping and other forms of e-commerce, or Google and search.

If the remedy to search abuse were to provide access to the underlying relevance engine, rivals could present and display products in any order they liked. New SERP businesses could then show relevant results at the top of pages and help consumers find useful information.

Businesses, such as Apple, could get access to Google’s relevance engine and simply provide the most relevant results, unpolluted by Google products. They could alternatively promote their own products and advertise other people’s products differently. End-users would be able to make informed choices based on different SERPs.

In many cases, the restoration of competition in advertising requires increased familiarity with the suppressed brand. Where competing publishers’ brands have been excluded, they must be promoted. Their lack of visibility can be rectified by boosting those harmed into rankings for equivalent periods of time to the duration of their suppression. This is like the remedies used for other forms of publication tort. In successful defamation claims, the offending publisher must publish the full judgment with the same presentation as the offending article and displayed as prominently as the offending article. But the harm here is not to individuals; instead, the harm redounds to alternative publishers and online advertising systems carrying competing ads.

In sum, the proper remedy is one that rectifies the brand damage from suppression and lack of visibility. Remedies need to address this issue and enable publishers to compete with Google as advertising outlets. Identifying a remedy that rectifies the suppression of relevance leads to the conclusion that competition between search-results-page businesses is needed. Competition can only be remedied if access is provided to the Google relevance engine. This is the only way to allow sufficient competitive pressure to reduce ad prices and provide consumer benefits going forward.

The authors are Chair Antitrust practice, Associate, and Paralegal, respectively, of Preiskel & Co LLP. They represent the Movement for an Open Web versus Google and Apple in EU/US and UK cases currently being brought by their respective authorities. They also represent Connexity in its claim against Google for damages and abuse of dominance in Search (Shopping).

Neoliberal columnist Matt Yglesias recently weighed into antitrust policy in Bloomberg, claiming falsely that the “hipsters” in charge of Biden’s antitrust agencies were abandoning consumers and the war on high prices. Yglesias thinks this deviation from consumer welfare makes for bad policy during our inflationary moment. I have a thread that explains all the things he got wrong. The purpose of this post, however, is to clarify how antitrust enforcement has changed under the current regime, and what it means to abandon antitrust’s consumer welfare standard as opposed to abandoning consumers.

Ever since the courts embraced Robert Bork’s demonstrably false revisionist history of antitrust’s goals, consumer welfare became antitrust’s lodestar, which meant that consumers sat atop antitrust’s hierarchy. Cases were pursued by agencies if and only if exclusionary conduct could be directly connected to higher prices or reduced output. This limitation severely neutered antitrust enforcement by design—with a two minor exceptions described below, there was not a single (standalone) monopolization case brought by the DOJ after U.S. v. Microsoft for over two decades—presumably because most harm in the modern (digital) age did not manifest in the form of higher prices for consumers. Under the Biden administration, the agencies are pursuing monopoly cases against Amazon, Apple, and Google, among others.

(For the antitrust nerds, the DOJ’s 2011 case against United Regional Health Care System included a Section 2 claim, but it was basically included to bolster a Section 1 claim. It can hardly be counted as a Section 2 case. And the DOJ’s 2015 case to block United’s alleged monopolization of takeoff and landing slots at Newark included a Section 2 claim. But these were just blips. Also the FTC pursued a Section 2 case prior to the Biden administration against Qualcomm in 2017.)

Even worse, if there was ever a perceived conflict between the welfare of consumers and the welfare of workers or merchants (or input providers generally), antitrust enforcers lost in court. The NCAA cases made clear that injury to college players derived from extracting wealth disproportionately created by predominantly Black athletes would be tolerated so long as viewers with a taste for amateurism were better off. And American Express stood for the principle that harms to merchants from anti-steering rules would be tolerated so long as generally wealthy Amex cardholders enjoyed more luxurious perks. (Patrons of Amex’s Centurian lounge can get free massages and Michelle Bernstein cuisine in the Miami Airport!) The consumer welfare standard was effectively a pro-monopoly policy, in the sense that it tolerated massive concentrations of economic power throughout the economy and firms deploying a surfeit of unfair and predatory tactics to extend and entrench their power.

Labor Theories of Harm in Merger Enforcement

In the consumer welfare era, which is now hopefully in our rear-view mirror, labor harms were not even on the agencies’ radars, particularly when it came to merger review. By freeing the agencies of having to construct price-based theories of harm to consumers, the so-called hipsters have unleashed a new wave of challenges, reinvigorating merger enforcement, particularly in labor markets. In October 2022, the DOJ stopped a merger of two book publishers on the theory that the combination would harm authors, an input provider in book production process. This was the first time in history that a merger was blocked solely on the basis of a harm to input providers.

And the DOJ’s complaint in the Live Nation/Ticketmaster merger spells out harms to, among other economic agents, musicians and comedians that flow from Live Nation’s alleged tying of its promotion services to access to its large amphitheaters. (Yglesias incorrectly asserted that DOJ’s complaint against Live Nation “is an example of the consumer-welfare approach to antitrust.” Oops.) The ostensible purpose of the tie-in is to extract a supra-competitive take rate from artists.

Not to be outdone, in two recent complaints, the FTC has identified harms to workers as a critical part of their case in opposition to a merger. In its February 2024 complaint, the FTC asserts, among other theories of harm, that for thousands of grocery store workers, Kroger’s proposed acquisition of Albertsons would immediately weaken competition for workers, putting downward pressure on wages. That the two supermarkets sometimes poach each other’s workers suggests that workers themselves could leverage one employer against the other. Yet the complaint focuses on the leverage of the unions when negotiating over collective bargaining agreements. If the two supermarkets were to combine, the complaint asserts, the union would lose leverage in its dealings with the merger parties over wages, benefits, and working conditions. Unions representing grocery workers would also lose leverage over threatened boycotts or strikes.

In its April 2024 complaint to block the combination of Tapestry and Capri, the FTC asserts, among other theories of harm, that the merger threatens to reduce wages and degrade working conditions for hourly workers in the affordable handbag industry. The complaint describes one episode in July 2021 in which Capri responded to a pubic commitment by Tapestry to pay workers at least $15 per hour with a $15 per hour commitment of its own. This labor-based theory of harm exists independently of the FTC’s consumer-based theory of harm.

Labor Theories of Harm Outside of Merger Enforcement

The agencies have also pursued no-poach agreements to protect workers. A no-poach agreement, as the name suggests, prevents one employer from “poaching” (or hiring away) a worker from its competitors. The agreements are not wage-fixing agreements per se, but instead are designed to limit labor mobility, which economists recognize is key to wage growth. In October 2022, a health care staffing company entered into a plea agreement with the DOJ, marking the Antitrust Division’s first successful prosecution of criminal charges in a labor-side antitrust case. The DOJ has tried three criminal no-poach cases to a jury, and in all three the defendants were acquitted. For example, in April 2023, a court ordered the acquittal of all defendants in a no-poach case involving the employment of aerospace engineers. (Disclosure: I am the plaintiffs’ expert in a related case brought by a class of aerospace engineers.) Despite these losses, AAG Jonathan Kanter is still committed as ever to addressing harms to labor with the antitrust laws.

And the FTC has promulgated a rule to bar non-compete agreements. Whereas a no-poach agreement governs the conduct among rival employers, a non-compete is an agreement between an employer and its workers. Like a no-poach, the non-compete is designed to limit labor mobility and thereby suppress wages. Having worked on a non-compete case for a class of MMA fighters against the UFC that dragged on for a decade, I can say with confidence (and experience) that a per se prohibition of non-competes is infinitely more efficient than subjecting these agreements to antitrust’s rule-of-reason standard. Again, this deviation from consumer welfare has proven controversial among neoliberals; even the Washington Post editorial board penned as essay on why high-wage workers earning over $100,000 per year should be exposed to such encumbrances.

Consumers Still Have a Cop on the Beat

If you take Yglesias’s depiction literally, it means that the antitrust agencies under Biden have abandoned the protection of consumers. But nothing can be further from the truth. Antitrust enforcers can walk and chew gum at the same time. The list of enforcement actions on behalf of consumers is too long to reproduce here, but to summarize a few recent highlights:

- FTC blocked Illumina’s acquisition of Grail on behalf of cancer patients;

- FTC induced Nvidia to call of its attempt to acquire Arm on behalf of direct and indirect purchasers of semiconducter chips;

- DOJ blocked a merger of JetBlue and Spirit to protect travelers;

- FTC persuaded a federal court to force generic drug maker Teva to delist five unlawful patent listings on asthma inhalers in the FDA’s Orange Book on behalf of asthma patients;

- FTC is pursuing Amazon for alleged subscription traps and dark patterns on behalf of subscribers of Amazon’s Prime video service; the FTC pursued fraud cases against firms, including Williams-Sonoma, for made in the USA claims;

- FTC took action against bill payment company Doxo for misleading consumers, tacking on millions in junk fees;

- DOJ has joined with multiple states to sue Apple for monopolizing smartphone markets on behalf of iPhone users;

- DOJ induced a subsidiary of Chiquita to abandon its proposed acquisition of Dole’s Fresh Vegetables division on behalf of vegetable consumers; and

- DOJ secured guilty pleas from two Michigan companies and two individuals for their roles in conspiracies to rig bids for asphalt paving services contracts in the State of Michigan.

Presumably Yglesias and his neoliberal clan have access to Google Search, Lina Khan’s Twitter handle, or the Antitrust Division’s press releases. It only takes a few keystrokes to learn of countless enforcement actions brought on behalf of consumers. Although this view is a bit jaded, one interpretation is that this crowd, epitomized by the Wall Street Journal editorial board and its 99 hit pieces against Chair Khan, uses the phrase “consumer welfare” as code for lax enforcement of antitrust law. In other words, what really upsets neoliberals (and libertarians) is not the abandonment of consumers, but instead any enforcement of antitrust law, particularly when it (1) deprives monopolists from expanding their monopolies to the betterment of their investors or (2) steers profits away from employers towards workers. In my darkest moments, I suspect that some target of an FTC or DOJ investigation funds neoliberal columnists and journals—looking at you, The Economist—to cook up consumer-welfare-based theories of how the agencies are doing it wrong. All such musings should be ignored, as the antitrust hipsters are alright.

There is a tension in the discourse as to the purpose of antitrust policy. In one camp, consumer welfare still reigns supreme. In another, there is greater acceptance that the consumer welfare standard is flawed, or at least controversial. Disciples of the first camp argue that antitrust policy should focus exclusively on increasing output as a proxy for consumer welfare.

Looking backwards, some have argued that the SCOTUS antitrust decisions focus almost entirely on output and price, consistent with consumer welfare. But is that how we should appraise what the Court was doing?

This short missive argues that SCOTUS does not articulate that it is applying consumer welfare. Even if it did, it does not tether that policy to notions of Congressional intent behind the antitrust laws. Indeed, where SCOTUS has said it is embracing Congressional intent, its opinion directly contradicts the notions of consumer welfare.

In a recent paper posted to SSRN titled “Antitrust’s Goals in the Federal Courts,” Herb Hovenkamp argues that to understand antitrust’s objective, we should focus on the words of SCOTUS and the federal courts: “Nearly all of this paper consists of statements from the Supreme Court and lower federal courts and concerns how they define and identify the goals of the antitrust laws.” It bears noting that Hovenkamp has been a strong advocate for consumer welfare theory, which would put him in the first camp. As Hovenkamp pointed out in a previous paper, “In sum, courts almost invariably apply a consumer welfare test.” And as Hovenkamp stated in yet another paper, there is good reason for the courts to do so: “it is a reasonable supposition that consumer welfare is maximized by offering consumers the best quality at the lowest price.”

While others have attempted to insert other policies into consumer welfare—or at least claim it is possible that other policies fit nicely within consumer welfare—the lodestar has always been output. As Hovenkamp professed: “[T]he country is best served by a more-or-less neoclassical antitrust policy with consumer welfare, or output maximization, as its guiding principle.”

Hovenkamp is correct that the courts have used the term consumer welfare. But the push for consumer welfare was not started in the Supreme Court, and the term has not been applied consistently in the way antitrust advocates of the consumer welfare standard might think.

Reading the tea leaves

The first mention of the words “consumer welfare” comes from U.S. v. Dotterweich, a case that sought to interpret the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act of 1938. The act sought to protect “against abuses of consumer welfare growing out of inadequacies in the Food and Drugs Act of June 30, 1906.”

It is not until 1976, in the Ninth Circuit’s case GTE Sylvania v. Cont’l T.V. Inc., that a court adopted the view that the purpose of antitrust was to protect consumer welfare. “Since the legislative intent underlying the Sherman Act had as its goal the promotion of consumer welfare, we decline blindly to condemn a business practice as illegal per se because it imposes a partial, though perhaps reasonable, limitation on intrabrand competition, when there is a significant possibility that its overall effect is to promote competition between brands.” The Court’s footnote 39 cites to Robert Bork’s 1966 piece. The notion of consumer welfare stayed in the Ninth Circuit for a few years, with Boddicker v. Arizona State Dental Ass’n and Moore v. James H. Matthews & Co.

In 1979, Chief Justice Burger wrote the Supreme Court’s decision in Sonotone. In that case, it appears Burger adopts Bork’s consumer welfare approach. But a careful reading of the full paragraph in which Burger cites Bork leaves that prescription uncertain:

Nothing in the legislative history of § 4 conflicts with our holding today. Many courts and commentators have observed that the respective legislative histories of § 4 of the Clayton Act and § 7 of the Sherman Act, its predecessor, shed no light on Congress’ original understanding of the terms “business or property.”4 Nowhere in the legislative record is specific reference made to the intended scope of those terms. Respondents engage in speculation in arguing that the substitution of the terms “business or property” for the broader language originally proposed by Senator Sherman5 was clearly intended to exclude pecuniary injuries suffered by those who purchase goods and services at retail for personal use. None of the subsequent floor debates reflect any such intent. On the contrary, they suggest that Congress designed the Sherman Act as a “consumer welfare prescription.” R. Bork, The Antitrust Paradox 66 (1978). Certainly, the leading proponents of the legislation perceived the treble-damages remedy of what is now § 4 as a means of protecting consumers from overcharges resulting from price fixing. E.g., 21 Cong.Rec. 2457, 2460, 2558 (1890). [emphasis added]

From there, the lower courts either cited Sonotone, Bork, the Merger Guidelines, or, in one case, Broadcast Music, which did not mention consumer welfare at all.

It was not until Jefferson Parish that the Court again mentions consumer welfare, but only in a concurrence by Justice O’Conner (again citing Broadcast Music). Justice O’Conner wrote: “Dr. Hyde, who competes with the Roux anesthesiologists, and other hospitals in the area, who compete with East Jefferson, may have grounds to complain that the exclusive contract stifles horizontal competition and therefore has an adverse, albeit indirect, impact on consumer welfare even if it is not a tie.” And in the same year, the Court in NCAA v. Board of Oklahoma again quoted Sonotone.

The words appear again in Atl. Richfield Co. v. USA Petroleum Co. in a dissent by Justice Stevens. But here the words are used in contradiction to notions of efficiency. Justice Stevens writes: “The Court, in its haste to excuse illegal behavior in the name of efficiency, has cast aside a century of understanding that our antitrust laws are designed to safeguard more than efficiency and consumer welfare, and that private actions not only compensate the injured, but also deter wrongdoers.” (emphasis added) The line suggests that the purpose of antitrust laws goes beyond short-run welfare maximization.

In his dissent in Eastman Kodak, Justice Scalia accuses the majority of ignoring consumer welfare in application of a per se rule against tying. Similarly, Justice O’Conner, citing consumer welfare, accuses the majority in Edenfield v. Zane of “taking a wrong turn” in areas of speech.

In FCC v. Beach Comm’n Inc., the Court wrestled with an FCC franchising requirement. In explaining its understanding of the purpose of antitrust laws, the Court mentions consumer welfare in a way potentially inconsistent with Bork’s treatment: “Furthermore, small size is only one plausible ownership-related factor contributing to consumer welfare. Subscriber influence is another.” These are not necessarily output- or price-related goals.

In the 1990s, there are two cases in which SCOTUS mentions consumer welfare. In Brooke Group v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco, the Court talks of its precedent, Utah Pie, in terms of how the case has “been criticized on the grounds that such low standards of competitive injury are at odds with the antitrust laws’ traditional concern for consumer welfare and price competition.” It does not, however, explain the meaning of consumer welfare. It merely quotes the usual Chicago School authors as to the point and moves on.

In the 2000s, consumer welfare became more prevalent in SCOTUS discussion, but again without explaining its meaning. Justice Stevens dissents in Granholm v. Heald against the removal of state wine restrictions because of Constitutional concerns. The Court in Weyerhauser notes that without recoupment, predatory pricing improves consumer welfare. Leegin, for all of its careful consideration of overturning Dr. Miles, mentions consumer welfare only three times, once quoting an Amicus brief. In Kirtsaeng, it quotes Hovenkamp in passing for that proposition. In Alston, the Court cautions that judges in implementing a remedy may affect outcomes worse than the market. In a maritime tort case, the dissent warned that overwarning regarding contaminants would injure consumer welfare. In Ohio v. American Express, the Court favorably cites to Leegin for the notion of consumer welfare, but only in passing. In Actavis, too, the dissent points to consumer welfare.

That is the extent of the Supreme Court’s wisdom on consumer welfare. For nearly 100 years, the phrase “consumer welfare” did not appear anywhere in antitrust lore. It did appear elsewhere, a point with which we must contend if the Court knew of term’s existence. Moreover, the Court has inconsistently used the term (within and beyond the antitrust laws), which suggests more haphazard citation than deliberate calculation. Or, perhaps more insidiously, an attempt to alter precedent via seemingly innocent citation leads to its increased usage in antitrust.

Put one shoe on before the other

In contrast to the obscure tea leaves from the aforementioned cases, the Court made a very precise pronouncement as to the purpose of antitrust in 1962. In Brown Shoe v. United States, the Court details the legislative history of the antitrust laws. The Court makes clear it is interpreting legislative history and the will of Congress, not creating its own policy:

In the light of this extensive legislative attention to the measure, and the broad, general language finally selected by Congress for the expression of its will, we think it appropriate to review the history of the amended Act in determining whether the judgment of the court below was consistent with the intent of the legislature.

That legislative history does not detail consumer welfare, and indeed it could not given the passage of the Sherman Act in 1890 and Alfred Marshall’s book, Principles of Economics, published in the same year. Looking backwards—from current understanding and implicitly thrusting that understanding on courts of yesteryear—is a problematic bias of this approach.

The Supreme Court goes on to note other aims of antitrust. It notes a focus on the rising tide of economic concentration. It even mentions some potential defenses, such as two small firms merging or a failing firm:

[A]t the same time that it sought to create an effective tool for preventing all mergers having demonstrable anti-competitive effects, Congress recognized the stimulation to competition that might flow from particular mergers. When concern as to the Act’s breadth was expressed, supporters of the amendments indicated that it would not impede, for example, a merger between two small companies to enable the combination to compete more effectively with larger corporations dominating the relevant market, nor a merger between a corporation which is financially healthy and a failing one which no longer can be a vital competitive factor in the market.

But it fails to mention other goals, including consumer welfare. And it explicitly rejects an efficiencies defense. Indeed, SCOTUS recognized that the goals of antitrust law may contradict expansions of output:

It is competition, not competitors, which the Act protects. But we cannot fail to recognize Congress’ desire to promote competition through the protection of viable, small, locally owned business. Congress appreciated that occasional higher costs and prices might result from the maintenance of fragmented industries and markets. It resolved these competing considerations in favor of decentralization. We must give effect to that decision.

In other words, prices might be higher and output lower when markets are less concentrated, but that is a price we are willing to pay in exchange for greater democracy and greater freedom from economic tyranny.

Looking backwards yields more heat than light

What all of this suggests is a strong movement and perhaps some misunderstandings by the Court about what consumer welfare means. Hovenkamp is right to be skeptical given, as he points out, SCOTUS does not often use the term. But it’s worse than that.

Where the trouble comes in is when Hovenkamp starts looking for output and price discussions as a proxy for consumer welfare. Here, he finds slightly more support in the tea leaves. But my critique of those considerations, beyond the points that overlap here, will have to wait for another blog post. At the very least, suffice it to say: If we’re using output as a measure of welfare, output holds the same problems as have been repeatedly stated as to consumer welfare. And if output is a not a proxy for consumer welfare, then why are we measuring it again?

Using the lens of our current understanding to assess older cases leads to biases that are more inclined to find the Court’s understanding is consistent with ours. Thorstein Veblen said it best: For the economist, “[a] gang of Aleutian Islanders slushing about in the wrack and surf with rakes and magical incantation for the capture of shell-fish are held, in point of taxonomic reality, to be engaged in a feat of hedonistic equilibr[ium] …. And that is all there is to it. Indeed, for economic theory of this kind, that is all there is to any economic situation.”

What we see looking backwards is not necessarily what the Court saw in the moment. And the only time the Court gave explicit meaning to antitrust’s purpose, it recognized that deconcentrating the economy might lead to higher prices and reduced output. More importantly, it recognized other antitrust goals apart those espoused by consumer welfare advocates.

Your intrepid writer, when not toiling for free in the basement of The Sling, does a fair amount of testifying as an expert economic witness. Many of these cases involve alleged price-fixing (or wage-fixing) conspiracies. One would think there would be no need to define the relevant market in such cases, as the law condemns price-fixing under the per se standard. But because of certain legal niceties—such as whether the scheme involved an intermediary (or ringleader) that allegedly coached and coaxed the parties with price-setting power—we often spend reams of paper and hundreds of billable hours engaging in what amounts to navel inspection to determine the contours of the relevant market. The idea is that if the defendants do not collectively possess market power in a relevant antitrust market, then the challenged conduct cannot possibly generate anticompetitive effects.

A traditional method of defining the relevant market asks the following question: Could a hypothetical monopolist who controlled the supply of the good (or services) that allegedly comprise the relevant market profitably raise prices over competitive levels? The test has been shortened to the hypothetical monopolist test (HMT).

It bears noting that there are other ways to define relevant markets, including by assessing the Brown Shoe factors or practical indicia of the market boundaries. The Brown Shoe test can be used independently or in conjunction with the HMT. But this alternative is beyond the scope of this essay.

Published in the Harvard Law Review in 2010, Louis Kaplow’s essay was provocatively titled “Why (Ever) Define Markets”? It’s a great question, and having spent 25-odd years in the antitrust business, I can provide a smart-alecky and jaded answer: The market definition exercise is a way for defendants to deflect attention away from the harms inflicted on consumers (or workers) and towards an academic exercise, which is admittedly entertaining for antitrust nerds. Don’t look at the body on the ground, with goo spewing out of the victim’s forehead. Focus instead on this shiny object over here!

And it works. The HMT commands undue influence in antitrust cases, with some courts employing the market-definition exercise as a make-or-break evidentiary criterion for plaintiffs, before considering anticompetitive effects. Other classic examples of market definition serving as a distraction include American Express (2018), where the Supreme Court even acknowledged evidence a net price increase yet got hung up over market definition, or Sabre/Farelogic (2020), where the court acknowledged that the merging parties competed in practice but not per the theory of two-sided markets.

A better way forward

When it comes to retrospective monopolization cases (aka “conduct” cases), there is a more probative question to be answered. Rather than focusing on hypotheticals, courts should be asking whether a not-so-hypothetical monopolist—or collection of defendants that could mimic monopoly behavior—could profitably raise price above competitive levels by virtue of the scheme. Or in a monopsony case, did the not-so-hypothetical monopsonist—or collection of defendants assembled here—profitably reduce wages below competitive levels by virtue of the scheme? Let’s call this alternative the NSHMT, as we can’t compete against the HMT without our own clever acronym.

Consider this fact pattern. A ringleader, who gathered and then shared competitively sensitive information from horizontal rivals, has been accused of orchestrating a scheme to raise prices in a given industry. After years of engaging in the scheme, an antitrust authority began investigating, and the ring was disbanded. On behalf of plaintiffs, an economist builds an econometric model that links the prices paid to the customers at issue—typically a dummy variable equal to one when the defendant was part of the scheme and zero otherwise—plus a host of control variables that also explain movements in prices. After controlling for many relevant (i.e., motivated by record evidence or economic theory) and measurable confounding factors, eliminating any variables that might serve as mediators of the scheme itself, the econometric model shows that the scheme had an economically and statistically significantly effect of artificially raising prices.

Setting aside any quibbles that defendants’ economists might have with the model—it is their job to quibble over modeling choices while accepting that the challenged conduct occurred—the clear inference is that this collection of defendants was in fact able to raise prices while coordinating their affairs through the scheme. Importantly, they could not have achieved such an outcome of inflated prices unless they collectively possessed selling power. (Indeed, why would defendants engage in the scheme in the first place, risking antitrust liability, if higher profits could not be achieved?) So, if we are trying to assemble the smallest collection of products such that a (not-so) hypothetical seller of such products could exercise selling power, we have our answer! The NSHMT is satisfied, which should end the inquiry over market power.

(Note that fringe firms in the same industry might weakly impose some discipline on the collection of firms in the hypothetical. But the fringe firms were apparently not needed to exercise power. Hence, defining the market slightly more broadly to include the fringe is a conservative adjustment.)

At this point, the marginal utility of performing a formal HMT to define the relevant market based on what some hypothetical monopolist could pull off is dubious. I use the modifier “formal” to connote a quantitative test as to whether a hypothetical monopolist who controlled the purported relevant market could increase prices by (say) five percent above competitive levels.

The formal HMT has a few variants, but a standard formulation proceeds as follows. Step 1: Measure the actual elasticity of demand faced by defendants. Step 2: Estimate the critical elasticity of demand, which is the elasticity that would make the hypothetical monopolist just indifferent between raising and not raising prices. Step 3: Compare the actual to the critical elasticity; if the former is less than the latter, then the HMT is satisfied and you have yourself a relevant antitrust market! An analogous test compares the “predicted loss” to the “critical loss” of a hypothetical monopolist.

For those thinking the New Brandeisians dispensed with such formalism in the newly issued 2023 Merger Guidelines, I refer you to Section 4.3.C, which spells out the formal HMT in “Evidence and Tools for Carrying Out the Hypothetical Monopoly Test.” To their credit, however, the drafters of the new guidelines relegated the formal HMT to the fourth of four types of tools that can be used to assess market power. See Preamble to 4.3 at pages 40 to 41, placing the formal HMT beneath (1) direct evidence of competition between the merging parties, (2) direct evidence of the exercise of market power, and (3) the Brown Shoe factors. It bears noting that the Merger Guidelines were designed with assessing the competitive effects of a merger, which is necessarily a prospective endeavor. In these matters, the formal HMT arguably can play a bigger role.

Aside from generating lots of billable hours for economic consultants, the formal HMT in retrospective conduct cases bears little fruit because the test is often hard to implement and because the test is contaminated by the scheme itself. Regarding implementation, estimating demand elasticities—typically via a regression on units sold—is challenging because the key independent variable (price) in the regression is endogenous, which when not correctly may lead to biased estimates, and therefore requires the economist to identify instrumental variables that can stand in the shoes of prices. Fighting over the proper instruments in a potentially irrelevant thought experiment is the opposite of efficiency! Regarding the contamination of the formal test, we are all familiar with the Cellophane fallacy, which teaches that at elevated prices (owing to the anticompetitive scheme), distant substitutes will appear closer to the services in question, leading to inflated estimates of the actual elasticity of demand. Moreover, the formal HMT is a mechanical exercise that may not apply to all industries, particularly those that do not hold short-term profit maximization as their objective function.

The really interesting question is, What happens if the NSHMT finds an anticompetitive effect owing to the scheme—and hence an inference of market power—but the formal HMT finds a broader market is needed? Clearly the formal HMT would be wrong in that instance for any (or all) of the myriad reasons provided above, and it should be given zero weight by the factfinder.

A special form of direct proof

An astute reader might recognize the NSHMT as a type of direct proof of market power, which has been recognized as superior to indirect proof of market power—that is, showing high shares and entry barriers in a relevant market. As explained by Carl Shapiro, former Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Economics at DOJ: “IO economists know that the actual economic effects of a practice do not turn on where one draws market boundaries. I have been involved in many antitrust cases where a great deal of time was spent debating arcane details of market definition, distracting from the real economic issues in the case. I shudder to think about how much brain damage among antitrust lawyers and economists has been caused by arguing over market definition.” Aaron S. Edlin and Daniel L. Rubinfeld offered this endorsement of direct proof: “Market definition is only a traditional means to the end of determining whether power over price exists. Power over price is what matters . . . if power can be shown directly, there is no need for market definition: the value of market definition is in cases where power cannot be shown directly and must be inferred from sufficiently high market share in a relevant market.” More recently, John Newman, former Deputy Director of the Bureau of Competition at the FTC, remarked on Twitter: “Could a company that doesn’t exist impose a price increase that doesn’t exist of some undetermined amount—probably an arbitrarily selected percentage—above a price level that probably doesn’t exist and may have never existed? In my more cynical moments, I occasionally wonder if this question is the right one to be asking in conduct cases.”

I certainly agree with these antitrust titans that direct proof of power is superior to indirect proof. Let me humbly suggest that the NSHMT is distinct from and superior to common forms of direct proof. Common forms of direct proof include evidence that the defendant commands a pricing premium over its peers (or imposes a large markup), as determined by some competitive benchmark (or measure of incremental costs), or engages in price discrimination, which is only possible if it faces a downward-sloping demand curve. The NSHMT is distinct from these common forms of direct evidence because it is tethered to the challenged conduct. It is superior to these other forms because it addresses the profitability of an actual price increase owing to the scheme as opposed to levels of arguably inflated prices. Put differently, it is one thing to observe that a defendant is gouging customers or exploiting its workers. It is quite another to connect this exploitation to the scheme itself.

Regarding policy implications, when the NSMHT is satisfied, there should be no need to show market power indirectly via the market-definition exercise. To the extent that market definition is still required, when there is a clear case of the scheme causing inflated prices or lower output or exclusion in monopolization cases, plaintiffs should get a presumption that defendants possess market power in a relevant market.

In summary, for merger cases, where the analysis focuses on a prospective exercise of power, the HMT might play a more useful role. In merger cases, we are trying to predict the profitability of some future price increase. Even in merger cases, the economist might be able to exploit price increases (or wage suppression) owing to prior acquisitions, which would be a form of direct proof. For conduct cases, however, the NSHMT is superior to the HMT, which offers little marginal utility for the factfinder. The NSHMT just so happens to inform the profitability of an actual price hike by a collection of actual firms that wield monopoly power, as opposed to some hypothetical monopolist. And it also helpfully focuses attention on the anticompetitive harm, where it rightly belongs. Look at the body on the ground and not at the shiny object.

After about a decade of teaching, it finally occurred to me that interviewing an accomplished economist (or economic critic) would be more entertaining—and hopefully more educational—than asking students to listen to me wax on about economic expert “war stories” for two hours. Also, by inviting a book author, I could compel students to digest the reading material before class, by submitting ten original questions with pinpoint cites to the reading in advance of the lecture. But which economist would I invite?

I’ve always been fascinated with books about the influence of economics on the law and how the economic mindset has largely screwed up our society; books like MacLean’s Democracy in Chains, Appelbaum’s The Economists’ Hour, or Popp Berman’s Thinking Like an Economist. (A sub-strand of this genre by Wu, Stoller, Philippon, Teachout, Dayen, and several others explores how Chicago School economists neutered antitrust enforcement, to the betterment of monopolists.) The latest installment in this school of thought is Economics in America: An Immigrant Economist Explores the Land of Inequality, by Angus Deaton.

I was confident that Professor Deaton, having won the Nobel Prize in 2015 and presumably having more important things to do than speak with undergraduates in an economics department with a heterodox reputation, would either ignore my invite or politely decline. To my delight, I was wrong, per usual. And the experience was magical. (Popp Berman spoke to my class as well this semester, and Deaton calls her book “persuasive.”)

Economics in America is not Deaton’s first popular (and non-technical) book. Along with Anne Case, he is the author of Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton Press 2021). For those who are too busy to read it, Case and Deaton penned a wonderful op-ed about these deaths in the New York Times. Deaton’s research focuses primarily on poverty, inequality, health, well-being, and economic development. In the technical realm, he is the author, along with John Muellbauer, of Economics and Consumer Behavior (Cambridge Press 1980), which was used in my first-year microeconomics course in graduate school.

Deaton’s three degrees in economics were earned at the University of Cambridge. He came to America with an offer to teach at Princeton. When he arrived, Ronald Reagan was dismantling the welfare state and regulation, as government interference in markets—and Keynesian economics generally—was blamed for stagflation in the late 1970s. (Keynesianism seems to be have been reborn in the aftermath of the Covid shock, with both parties embracing public-sector stimulus to revive economic fortunes.) Deaton was surprised by Americans’ apathetic attitudes towards inequality and poverty generally, especially compared to the widespread support of the safety net that had been erected in his home of Britain to fight disease and homelessness.

Gatekeepers Gonna Gatekeep

Economics in America begins with the story of how Card and Krueger’s seminal work on the minimum wage, which produced a result counter to the economic orthodoxy that the minimum wage reduced employment and counter to the interests of the business community generally and the fast-food industry in particular. Their findings were roundly rejected by the economics establishment or “gatekeepers,” as I like to call them. He chronicles the attacks by Paul Craig Roberts, Thomas Sowell, the Wall Street Journal editorial page (surprise!), David Neumark (whose minimum wage research, as the book notes, is funded by business groups), Finis Welch, and June O’Neill.

For those who are new to the debate, Card and Krueger exploited a natural experiment in two neighboring states (New Jersey and Pennsylvania) to show that that increasing the minimum wage in New Jersey did not increase unemployment, as the simplistic economic models would have predicted. One explanation for their surprising result was that employers like Wendy’s, despite their small footprint in fast-food employment within a commuting zone, enjoy a modicum of wage-setting power over their employees, due to high switching costs caused in part by firm-specific training. These switching costs in turn allow these employers to absorb increases in labor costs from a minimum wage hike without cutting jobs. (The profession reacted similarly to the notion that profiteering and price gouging by large corporations was to blame for some material portion of inflation. I had to block so many IO economists on Twitter!) Deaton concludes the chapter by noting that conventional wisdom in economics is “weighted towards capital and against labor.” But he never goes so far as to say that economics has been corrupted by capital—that is, in their constant pursuit of funding, economists say whatever capitalists want to hear. (He is more diplomatic than me.)

There’s a great revelation early in the book that Barack Obama, during a debate with Hillary Clinton, denounced the insurance mandate—which would require everyone to have coverage and thereby address the adverse selection problem—as being unnecessary to an effective health care overhaul. Of course, the mandate was ultimately included in Obamacare. I feel like this episode reveals a lot about Obama’s commitment to progressive values. That plus surrounding himself with neoliberals like Jason Furman and Larry Summers, who have revealed themselves to (a) be hostile to government spending even in a recession (now twice) and (b) subscribe to the outmoded theory that inflation is driven by wage demands (aka greedy workers).

In a chapter devoted to poverty, Deaton elegantly describes the official poverty metric from the Census Bureau as a “statistical stupidity,” because it fails to account payments from government programs. Thus, the war on poverty can never be won.

Poverty-Inflicting Corporate Behaviors

It is curious why a Democratic candidate (or office holder) cannot explain this statistical flaw to voters. Deaton ends the chapter by noting that donating for poverty relief in the places in the United States where jobs are being lost would draw attention “to those corporate behaviors that were contributing to that domestic poverty” (emphasis added). The book does not spell out, at least here, which “corporate behaviors” he had in mind, and how they contribute to poverty. Later in the book, however, Deaton cites corporate acquisitions—in particular, rich companies buying up competitors before they are a threat—as a mechanism by which income inequality (aka extreme wealth) limits opportunities. Though he did not list them, other anticompetitive “corporate behaviors,” including no-poach provisions and non-competes, also might be contributing to domestic poverty, by restricting worker mobility and thereby reducing their best outside options. (During my interview, Deaton confirmed that these other corporate behaviors are contributing to poverty.)

In a chapter devoted to inequality, Deaton discusses the hostility among Chicago School economists to the concepts of fairness and inequality. It’s pretty obvious that their preferred economic policies will “score” poorly on those dimensions, but will “score” better on their preferred metrics such as efficiency or output. The strategy of moving the goalposts to accommodate one’s preferred policies seems so obvious in hindsight. It begs the question as to why these results-oriented approaches were not sniffed out by courts.

Economics in America explains how income equality is perpetuated by market forces. Deaton writes that “income inequality seems to get in the way of [economic] opportunity.” One mechanism by which this causal story could occur is if the rich hoard the best opportunities for themselves and their children. (This happens outside the pay-to-play scheme for wealthy parents to get their children into top universities orchestrated by Rick Singer, no relation.) Another mechanism by which inequality impairs opportunity is that as disproportionately poor workers get sick while their wealthier peers stay healthy, the wealth gaps will widen.

Antitrust as an Anti-Poverty Tool

The same chapter explains how growing concentration among companies could give employers greater buying power over workers, increasing income inequality. This means that, contra the opinions of Jason Furman—who recently pushed back on a brilliant op-ed by Tim Wu—more antitrust enforcement in labor markets could be used to reduce income inequality. (In disclosure, I serve as an expert for workers in several ongoing labor antitrust matters, including the recently settled UFC monopsony case.) It bears noting that the consumer welfare standard of antitrust, another Chicago School invention, was presumably designed to divert attention away from worker harms in labor markets and towards consumer harms in product markets.

Deaton also hints, contra neoliberal orthodoxy, that a reduction in immigration might reduce income inequality, acknowledging that many economists might disagree. He never spells out the mechanism here. But he suggests that neoliberal economists may have committed some errors in measuring the impact of immigration on wages. My surmise, sticking with the economics-is-corrupt theme, is that economists instinctively defend immigration because immigration benefits large employers—by providing a ready pool of workers willing to supply labor at wages below competitive levels—and because economists are generally auditioning for income from large employers. Indeed, Deaton later writes that “the public perception [is] that economists are apologists for capitalism or they are shills for greedy and immoral corporations.”

So Did Economists Break the Economy?

Deaton finishes the book by exploring whether economists are to blame for breaking the economy and “creating the forces that swamp us today.” He notes that Larry Summers used his influence as Treasury secretary from 1999 to 2001 to “weaken restrictions on the international flow of speculative funds, as well as on derivatives and other more exotic instruments on Wall Street.” In critiquing these and other neoliberal policies that gave birth to the Great Recession, Deaton writes: “This is a tale that cannot be told too often, of government-enabled rent seeking and destruction supported by the ideology of market fundamentalism.”

He laments the anti-Keynesianism that grips the Republican Party (save for the aforementioned deficit spending under Donald Trump during Covid). Economist Robert Barro of Harvard pioneered the libertarian theory that, in response to fiscal stimulus, consumers will pare back spending in fear of future higher taxes on themselves or their descendants, thereby neutralizing the impact of the stimulus. Per Deaton, such “insanity is an embarrassment, and the fact that Barro is taken seriously—and is a professor at Harvard, rather than a fringe blogger—is a sure indication that, indeed, macroeconomics has regressed, not progressed, since 1936.”

In writing about the deaths of despair, Deaton and Case saw the loss of jobs, via globalization and technology upheaval, as the key causal factor; without a job, a desperate American is more willing to engage in harmful activities, including drug abuse and eating poorly. Conservative critiques flipped the story around, blaming the drugs as the cause of despair (rather than the symptom), and speculating that the government was subsidizing opioids through Medicaid. Never mind that only eight percent of opioid prescriptions between 2006 and 2015 were paid for by Medicaid. Deaton explains that the right-wing prescription, often repeated by economists, is “to tell people to be more virtuous,” but that “[e]conomics does not have to be like this.” He concludes that “Joe Biden does not listen to economists in the way that Obama or Clinton did, something that arguably makes him a better president” (emphasis added). This is a sad reflection on the dismal science.

Alas, Deaton offers a prescription for a course correction: “Economics should be about understanding the reason for and doing away with the sordidness and joylessness that come with poverty and deprivation.” The final chapter explains how the “discipline has become unmoored from its proper basis, which is the study of human welfare.” A new breed of progressive economists (count me in) “worry about inequality and are willing to use redistribution to correct the failures of the market, even at the expense of some loss of efficiency.” In addition to redistribution, Deaton writes that we should embrace predistribution policies, or “the mechanism that determine the distribution of income in the market itself, before taxes and transfers.” Among these policies, he endorses distinctly heterodox ideas such as promoting unions, immigration control, tariffs, job preservation, and industrial policy.

Deaton has charted the new course. Will any economists follow it?

As the name implies, Congress passed the antitrust laws to remedy the problem of the trusts—the great agglomerations of capital harming working people. Yet, from that very beginning, the forces of corporate power and oligarchy have used the antitrust laws to attack working people. When the federal government first deployed the antitrust laws against coordinated economic power, they did not use them against trusts like Standard Oil or railroad monopolists; instead, they used them against people organizing workers to fight for better wages. By doing so, the federal government created a threat that haunted the labor movement for decades—the threat of the “labor injunction.” That threat remains today. And the federal government can take a simple step to combat it.

In 1999, while Bill Clinton was serving his second term, port truck drivers across the country decided to get organized and go on strike. But instead of solidarity with their strike action, they received a subpoena from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the threat of a lawsuit under the antitrust laws from their employers. Faced with the threat of legal action from the government and their employers, they abandoned their strike.

The FTC investigated the port truckers even though the antitrust laws specifically exempt labor organizing. These truckers are not the only workers that have been targeted by antitrust authorities. Music teachers, ice skating coaches, and public defenders have all faced the wrath of the FTC. Why? Because they were classified as independent contractors—a classification dictated by their employers. These cases raise a question central to American political economy: which workers have the right to organize?

The answer should be all workers. But, in reality, fewer and fewer workers can organize without the threat of a lawsuit under the antitrust laws.

Today, more and more workers are classified not as employees but as independent contractors in a practice called “workplace fissuring.” This practice is most visible for gig workers. Companies like Uber have fought tooth and nail to preserve their workers’ independent contractor status. But this practice is not limited to gig work companies. It has become a common tactic employed by predatory corporations in every industry. By doing so, they believe they can legally prevent collective action through the antitrust laws. And if you ask antitrust scholars like Herbert Hovenkamp, that Uber drivers are “selling a combination of their labor and usage of their cars” implies the labor exemption to antitrust might not protect them.

But the law and history prove those who would expose workers to antitrust liability wrong. In passing the labor exemption, Congress did not intend to just exempt employees, it aimed to cover all workers organizing to vindicate their rights. Indeed, the text of the Norris LaGuardia Act explicitly states the exemption is not limited to just those “stand[ing] in the proximate relation of employer and employee.” And the Clayton Act does not restrict the exemption’s coverage to employees, but instead states that “[n]othing contained in the antitrust laws shall be construed to forbid the existence and operation of labor…organizations, instituted for the purposes of mutual help[.]” (emphasis added)

Fortunately, this historically accurate interpretation of the law is gaining ground. In 2022, the First Circuit found that a group of independent contractor jockeys could legally organize and strike, rejecting a title-based approach in favor of one that focuses on whether or not workers were selling labor or goods. FTC Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya drew attention to this interpretation of the labor exemption in a speech at a Utah Project event in 2023 and a law review article published this month. (Full disclosure, I worked on this speech while in Commissioner Bedoya’s office and am co-author on the article). A detailed analysis by two NYU scholars has grounded a reading of the exemption which would cover many independent contractors in court precedent and textualist methods.

But this view of the law should be formalized. The FTC and Department of Justice (DOJ) should issue a policy statement declaring that the labor exemption covers independent contractors that are treated like workers, rather than like independent businesspeople, by the company that hired them. While such a policy statement would not be precedential, it would be important persuasive authority for any court examining this issue. It would also provide crucial cover for workers uncertain about whether or not their employers’ threats of legal action are valid. It could not stop an employer from seeking an old-school labor injunction against their workers, but it could help those workers win in court—especially if the enforcement agencies back up the statement with amicus briefs in those cases.

Most importantly, it would remove the real threat of federal prosecution hanging over the heads of American workers. It is the duty of “the most pro-union President…in American history” to remove that threat. The FTC and DOJ must state affirmatively: All workers, not just those granted employee status, have the right to organize and that right will not be abridged by the antitrust authorities. The Biden administration must bury the labor injunction once and for all.

Bryce Tuttle is a student at Stanford Law School. He previously worked in the office of FTC Commissioner Bedoya and in the Bureau of Competition.

“The nine most terrifying words in the English language are ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’” – Ronald Reagan

At recent events, Chair of the Federal Trade Commission and mug-emblazoner Lina Khan has taken to quoting Reagan’s cherished tagline above. Not to express ideological alignment, but as a springboard for workshopping her own modern twists on the perils of private tyranny: