Free trade is under increasing attack by both the progressive left and the populist right. Although the left and the right offer different policy solutions—the progressive left stresses combining industrial policy, antitrust policy, and support for labor with targeted tariffs, while the populist right advocates a wider use of tariffs combined with stricter immigration policy—supporters of both of these groups no longer adhere to the neoliberal free trade approach advocated by most economists. Are both of these voices misinformed about economics?

We argue that it is neoliberal economists who are wrong about the economics of trade. Economics textbooks and popular work by economists typically hide the unrealistic assumptions that are required to conclude that free trade as practiced by the United States is a beneficial policy overall, meaning that it is welfare-improving.

The Case for Free Trade: Comparative Advantage

The basis for the economic claim that free trade is beneficial is the early 19th century British political economist David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage. The basic logic is that it is always more efficient for each party engaged in trade to specialize in what they do best. Per this logic, even if your spouse can earn more money than you can and they can perform better childcare, if you are better at childcare than at earning money, the childcare should be assigned to you. Likewise, if each nation specializes in what they do best, and then trades with other nations for other goods, everyone benefits.

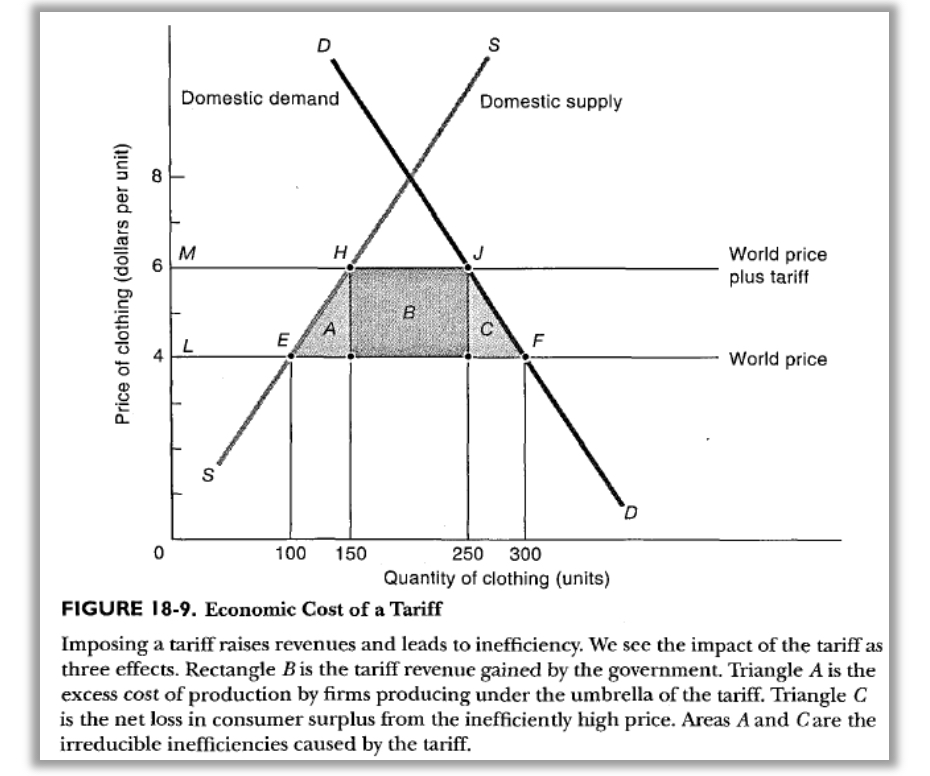

In the classic textbook treatment, the benefits of comparative advantage are expressed in diagrammatic form. For example, the famous textbook of Samuelson and Nordhaus (2010) uses the following graph to prove the loss in social surplus caused by tariffs.

In this graph, imposition of the tariff causes the domestic price level to rise from 4 to 6 (from the line to the line ). This price increase causes domestic consumption to fall from 300 to 250 units, which in turn causes consumer surplus to fall by area C. Interpret the “world price” horizontal line LF as the foreign supply curve and the foreign marginal cost curve, and interpret the “domestic supply” line SEHS as the domestic supply curve and the domestic marginal cost curve. The tariff causes domestic production to rise from 100 to 150 units, and area A is the increase in production costs caused by this shift from low-cost foreign producers to higher-cost domestic producers. The sum of A and C is the loss of social surplus caused by the tariff.

This demonstration has held great sway among economists. In covering the January 2025 meeting of the American Economic Association, the New York Times reported that “free trade is perhaps the closest thing to a universally held value among economists.” To back this up, the article cited a 2016 survey by the University of Chicago’s Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets of their panel of prominent academic economists from top universities, in which 39 out of 39 strongly disagreed or disagreed that “Adding new or higher import duties on products such as air conditioners, cars, and cookies—to encourage producers to make them in the U.S. —would be a good idea.” There was another survey performed by the Clark Center in 2018, in which 40 out of 40 of the panel disagreed that “Imposing new U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum will improve Americans’ welfare.” For a more general question asked in 2012, “Free trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment,” the votes were 35 strongly agree or agree, two were uncertain, and none disagreed.

The economic argument depicted by the diagram is unassailable, but only if several unsurfaced assumptions hold. Although many economists highly value logical argument, they are at the same time remarkably tolerant of unrealistic assumptions of the sort we are about to discuss.

The Failed Assumptions of the Free Trade Model

There are five assumptions (two explicit and three implicit) needed to support the free-trade argument as depicted in the diagram above.

The first explicit assumption is that there is full employment in the domestic economy. It is assumed that when workers are displaced by imports, they can easily become re-employed at the same wages. If this is not the case, then removal of a tariff causes a loss of social surplus (a loss of economic rent) in the domestic labor market, which the analysis based on the above figure misses because it only depicts the output market.

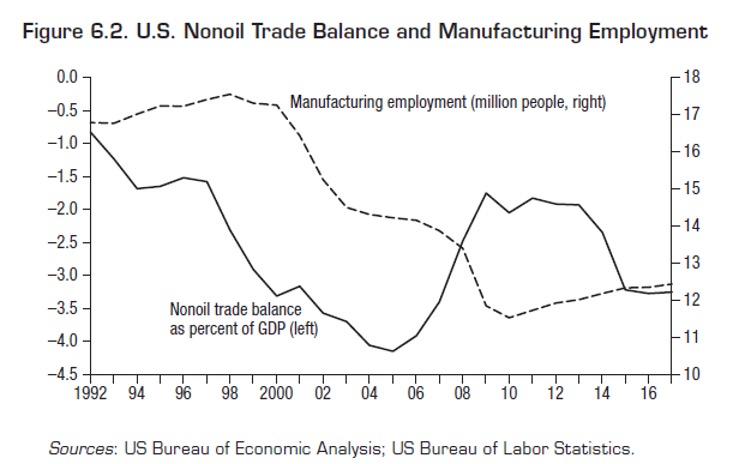

Yet the assumption of full employment does not hold empirically. On the contrary, here is a revealing graph from an article by Paul Krugman (2019).

Trade job loss has been 74 percent in manufacturing, which is one of the few sectors where non-college-degree-holding males could earn a good living. Contrary to free trade theory, the U.S. lost jobs, primarily in high tech, computer parts, electronics, and durable goods manufacturing. Between 2001 and 2018, EPI estimates that the U.S. lost 1,132,500 jobs to Chinese imports but only gained 175,800 jobs to exporting industries to China.

In their work on the China Syndrome, Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013) show that the impact on labor comes “less from its economy-wide impacts than from its disruptive effects on particular regions.” These disruptions would not have occurred if full employment, and frictionless re-employment, characterized the economy.

The second explicit assumption that undergirds the free trade theory is that there are no externalities. Pisano and Shih (2012) analyze the total impact of the loss of manufacturing jobs in particular regions. The impact can be enormous, stretching far beyond a manufacturing plant. Entire towns or cities can be hollowed out. A plant closure can destroy numerous small businesses, the tax base, and many complementary businesses. In addition, workers in the nontraded sector are hurt by an increased labor supply, and their bargaining power is undermined. None of these changes in social surplus are captured in the Samuelson and Nordhaus figure above.

Besides these two explicit assumptions, policy analysts who advocate free trade often make three more implicit assumptions, as enumerated by Fletcher (2011). These are also flawed.

The first implicit assumption is that comparative advantage results in short-run efficiencies that cause long term growth and development. The problem with this idea in practice is that comparative advantage is a static theory. The inside joke among economists is that each country should do what it is best at doing, and what underdeveloped countries are best at is underdevelopment.

The evidence is strongly contrary to this assumption. Indeed, no country has successfully developed under free trade. In his book Kicking Away the Ladder, Ha-Joon Chang reviews the development history of every developed country and shows that every one of them used significant tariffs as part of its development strategy. Joe Studwell, in How Asia Works, shows that all of the Asian Tiger countries used trade protection with government industrial policy to develop. So free trade is not a development strategy. It is a static policy that can impede development.

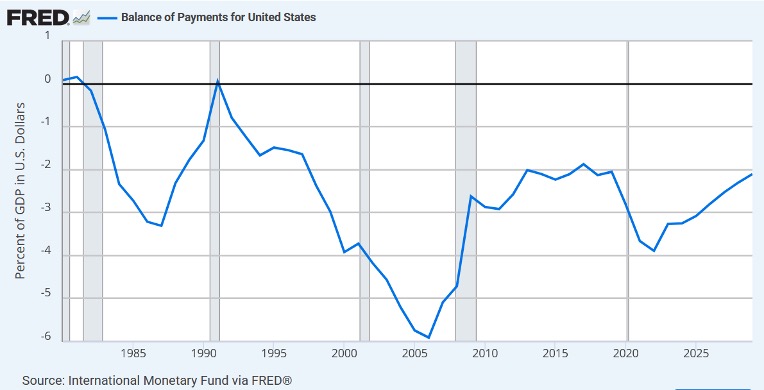

The second implicit assumption that undergirds free trade theory is that freely-floating currencies will keep trade balanced, limiting imports and ensuring that benefits exceed loses. This is not true, as trade with the U.S. has not been balanced for many decades per the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

After the U.S. liberalized capital markets in the 1980s, trade deficits were supported by capital movements into the United States. Foreigners have used their dollars to purchase U.S. securities and real estate, which does not increase U.S. productivity because it generates no new capital formation (at least directly).

The third implicit assumption is that the U.S. provides adequate compensation for job losses caused by international trade. On the contrary, Lori Kletzer (2001) analyzed the U.S. policy response to trade-induced job losses and found it to be woefully inadequate. By contrast, countries that have strong labor support policies (like strong social safety nets) are generally much better able to garner the benefit from international trade without suffering social and political costs from it.

In the absence of these five assumptions, the free trade argument is completely undermined.

And if these five weren’t enough, there is another, more basic assumption underlying the free trade argument that needs to be debunked—namely, the assumption that social surplus areas of the sort used in the graphic presentation of the free trade argument are a correct measure of welfare. For more on that, see our papers with Darren Bush.

Our position is not that free trade is never the correct policy. Comparative advantage exists; even permanent comparative advantage exists. But analysis of free trade policies should occur in a real-world framework, not one that makes important assumptions which do not hold, even approximately, in the real world.

The election results present a puzzle of sorts. On the one hand, voters expressed deep resentment towards inflation, under the belief that Biden contributed to rising prices, failed to address them, or both. On the other hand, Trump’s signature economic policy is tariffs—on imports from Mexico to Canada and now Israel—which most economists believe will raise prices. Why are voters, who are ostensibly so sensitive to high prices, willing to give Trump a pass on an obviously inflationary policy?

When I have posed this puzzle on Twitter, the standard neoliberal voices—from Jordan Weissmann to Eric Levitz to Matt Yglesias (aka “The Vox Boys”)—suggested that my brain is small. (Yes, the same Levitz who leaned entirely on an economist to interpret a contract for the counterintuitive proposition that insureds were immunized from Anthem’s proposed and now-retracted policy to restrict anesthesia coverage.) The Vox Boys reckon that voters put everyday low prices above all else. To believe this, however, you must also believe that voters don’t understand the implications of tariffs or don’t believe Trump will follow through with his threats. This neoliberal explainer is fairly unsatisfying, however, as it requires one to believe that voters are stupid.

An alternative explanation, which infuriates the Vox Boys, is that while voters care about low prices, they also care about other things like preserving blue-collar manufacturing jobs or supporting local businesses. To wit, voters tend to punish Democrats for removing trade barriers: A 2020 American Economic Review paper showed “trade-impacted commuting zones or districts saw an increasing market share for the Fox News channel (a rightward shift) … and a relative rise in the likelihood of electing a Republican to Congress (a rightward shift).” This desire to protect local businesses animates much of the New Brandeisian movement, which rejects the consumer welfare standard in antitrust, by among other things, recognizing harms to workers or small businesses.

Following the advice of her corporatist advisors like Tony West, Harris elected to attack Trump’s tariffs from the right, highlighting how the tariffs could raise prices. Indeed, the Harris campaign tweeted a video of Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell bashing Trump’s tariffs, a few weeks after Rampell called Harris’s price gouging proposal “communism.” These attacks moved exactly no one in Harris’s direction. And no wonder: The Democrats are supposed to stand up for labor, who are the biggest beneficiaries of tariffs, especially those who work in the tariff-protected industries. Progressive advocates like Zephyr Teachout were calling for a recalibration on the anti-tariff message, but were ignored. Another victory for the Vox Boys and Girls!

When I pointed out that Trump managed to purge the neoliberal free-trading ideology from his party’s platform, appealing smartly to voters who care about jobs as well as low prices, Levitz quote-tweeted a screen shot of his summary of a 2019 study (and a link to his Vox article), purporting to show that that American exporters that were most exposed to Trump’s tariffs on their inputs—think steel, aluminum, solar panels, and various Chinese goods—experienced lower export growth in 2018 and 2019 than exporters who were unaffected by the duties. Per the Vox Boys, tariffs create harms beyond higher prices.

Before getting into the details of the study, let me note two obvious things. First, from a political perspective, the welfare of large traders engaged in importing and exporting (aka “trading firms”) doesn’t get much play in election conversations; so this anti-tariff argument will again fall on deaf ears. Second, one can’t evaluate a tariff from a cost-benefit perspective without also studying the beneficiaries of the tariffs. By focusing on the welfare of trading firms, however, this study implicitly downplays the welfare of workers whose jobs were protected by the tariffs.

Regarding the merits of the underlying study (available here), the focus on the impact of Trump’s tariffs on exporter growth is curious. If larger or faster growing exporters were more exposed to the “treatment,” then their growth would be expected to slow relative to the “control” group (smaller exporters not exposed to Trump’s tariffs); it’s easier to “grow” from a smaller base. Indeed, the authors acknowledge the difference in the size of the two study groups at page 2:

We find that U.S. importers facing import tariff increases employed twice as many workers compared to the average importing firm and about nine times as many workers as the average firm. Similarly, we find that U.S. exporting firms facing retaliatory tariffs were more than three times larger than the average exporting firm. Thus, the tariff increases hit the very largest trading firms in the U.S. economy.” (emphasis added).

Figure 3 of the study shows that cumulative growth rate in exports for the treatment group exceeded the control group in the two years leading up to the tariffs, with the gap between the two shrinking in each month. It stands to reason that, even absent the tariffs, the growth rates of the two groups would have naturally converged. In fact, the two trendlines differed by approximately 10 log points in early 2016, with most exposed export sectors exceeding all other export sectors by a comparison of 3 log points to -14 log points, respectively. This difference shrank to nearly zero by the beginning of 2018. The reversal that occurred after January 2018 reflects a continuation of the opposing pre-tariff growth directions. Yet the use difference-in-differences (DID) estimation to recover a causal effect, as the authors of this study intended, critically rests upon the “parallel trend” assumption—namely, that had the treatment never occurred (i.e., tariffs had never been imposed), the relationship between the treated and control groups would have remained constant over time. But the authors casually mention parallel trends just once in a footnote, claiming “Figure 3 suggests parallel trends in the months prior to the trade war.” While that statement might be true for the few months right before the Trump tariffs, it ignores the plainly obvious longer trend of convergence. Violation of the parallel trends assumption can bias the estimated effect, undermining the researcher’s ability to ascribe a causal interpretation to the treatment.

Finally, the magnitude of the effect, assuming it’s properly measured, doesn’t sound debilitating for large exports. The authors find a decrease in “log points” of around one (slightly smaller in 2018, slightly larger in 2019), which can be interpreted as a percent change for small differences. By comparison, exports were growing by between four and six percent in the year leading up to Trump’s tariffs, per Figure 1. A decline of one percent in the growth rate of exports for the largest trading firms that import tariff-affected inputs might be a small price to pay for protecting jobs and domestic industries.

Focus on the jobs

Levitz also points readers to a 2019 staff working paper at the Federal Reserve as evidence that Trump’s tariffs harmed workers. Setting aside any infirmities in the estimation or interpretation of results, at least this study focuses on a meaningful outcome variable. The staff working paper purports to show that U.S. manufacturing industries more “exposed” to tariffs lose more jobs from rising input costs (channel one) and retaliatory tariffs (channel two) than jobs gained or preserved from import protection (channel three). Exposure to import protection for a given industry is measured as the share of domestic absorption of that industry affected by newly imposed tariffs; exposure to the other two channels is measured similarly. It follows that for any given industry, exposure along these three channels could vary dramatically.

This study also uses a DID method to uncover the effects of the tariffs. The authors note the “issue of differing trends across industries prior to the implementation of new tariffs”—an admission that parallel trends may not be satisfied—and seek to address it by (1) removing industry-specific trends in 2017, or (2) differencing out the pre-trend path for each coefficient. After these various contortions, they find that “shifting an industry from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile in terms of exposure to each of these channels of tariffs is associated with a reduction in manufacturing employment of 1.4 percent, with the positive contribution from the import protection effects of tariffs (0.3 percent) more than offset by the negative effects associated with rising input costs (-1.1 percent) and retaliatory tariffs (-0.7 percent).” (emphasis added). But this begs the question: What single industry would make such an equivalent move on each of these channels? If China is expected of dumping (say) solar panels, and Trump slaps a tariff on solar panels from China, why would the solar panel industry (now exposed to the import protection channel) be equally exposed to (say) rising input costs?

It would have been helpful for the authors to identify the aggregate employment effect across the three channels for any given industry. Were there industries with net job gains resulting from Trump’s tariffs? To wit, if an industry was only exposed to the import protection channel—that is, no input costs were increased by other tariffs and there was no retaliation for the industry in question—the best estimate of the jobs effect would be positive! By showing the size of the coefficients of the three channels for equal shifts in channel exposure, however, the authors have made it difficult to assess the economy-wide effects as well. We only know (assuming the specification is proper) of the relative magnitudes of the employment effects given a one percentage point exposure to each of the three channels. Tariff bashers will interpret the coefficients as if they can be summed up, but that is only for a hypothetical industry that experienced the same increase in exposure across all three channels.

This is not meant to impugn the integrity of either study. All empirical studies can be criticized. Rather, it is meant to suggest that the Vox Boys have found two studies that tell their story of tariff-induced harms and have decided to pump them up. But neither study materially advances the economic argument against tariffs.

In summary, the neoliberal critique of Trump’s tariffs finds little support in economics or among voters. The Vox Boys and Girls, who myopically focus on low prices over all other considerations, should be ignored. And Democratic Party should recalibrate their approach to tariffs, recognizing that, to be considered the party of labor once again, promoting labor interests should be their loadstar.