Healthcare in rural America has hit a crisis point. Although the health of people living in rural areas is worse than those living in metropolitan areas, rural populations are deprived of the healthcare services they deserve and need. Rural residents are more likely to be poor and uninsured than urban residents. They are also more likely to suffer from chronic conditions or substance-abuse disorders. Rural communities also experience higher rates of suicide than do communities in urban areas.

For people of color, life in rural America is even harder. Research demonstrates that racial and ethnic minorities in rural areas are less likely to have access to primary care due to prohibitive costs, and they are more likely to die from a severe health condition, such as diabetes or heart disease, compared to their urban counterparts.

Although rural residents in America experience worse health outcomes than urban residents, rural hospitals are closing at a dangerous rate. Rural hospitals experience a severe shortage of nurses and physicians. They also treat more patients who rely on Medicaid and Medicare, or who lack insurance altogether, which means that they offer higher rates of uncompensated care than urban hospitals. For these reasons, hospitals in rural areas are more financially vulnerable than hospitals in metropolitan areas.

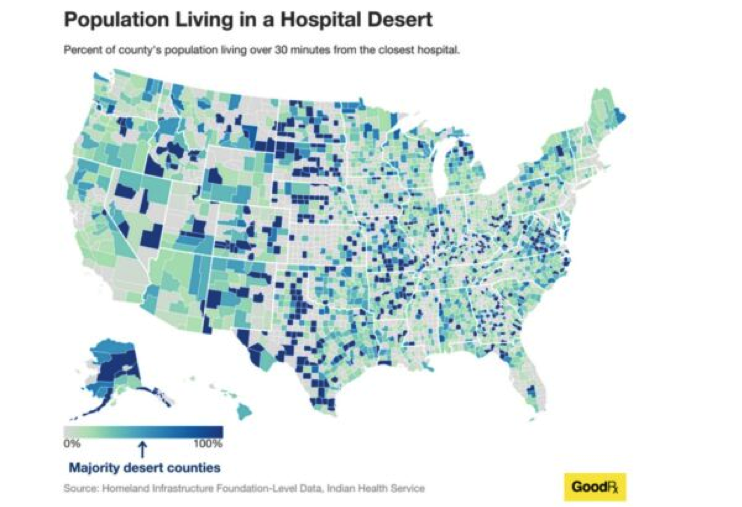

Indeed, recent data show that since 2005, more than 150 rural hospitals have shut their doors and more than 30% of all hospitals in rural areas are at immediate risk of closure. As hospital closures in rural America increase, the areas where residents lack geographic access to hospitals and primary care physicians, or “hospital deserts,” also increase in size and number.

This map is illustrative. It indicates two important things. First, in more than 20% of American counties, residents live in a hospital desert. Second, hospital deserts are primarily located in rural areas.

Empirical evidence demonstrates that hospital deserts reduce access to care for rural residents and exacerbate the rising health disparities in America. When a hospital shuts its doors, rural residents must travel long distances to receive any type of care. Rural residents, however, tend to be more vulnerable to overcoming these obstacles, as some of them do not even have access to a vehicle. For this reason, data show that rural residents often skip doctor appointments, delay necessary care, and stop adhering to their treatment.

Despite the magnitude of the hospital deserts problem and the severe harm they inflict on millions of Americans, public health experts warn that rural communities should not give up. For instance, Medicaid expansion and increased use of telemedicine can increase access to primary care for rural residents and thus can improve the financial stability of rural hospitals. When people lack access to primary care due to lack of coverage, they end up receiving treatment in the hospitals’ emergency departments. For this reason, research shows, rural hospitals offer very high rates of uncompensated care, which ultimately contributes to their closure.

This Antitrust Dimension of Hospital Deserts in Rural America

In a new piece, the Healing Power of Antitrust, I explain that these proposals, albeit fruitful, may fail to cure the problem. The problem of hospital deserts is not only the result of the social and demographic characteristics of rural residents, or the increased level of uncompensated care rural hospitals offer. The hospital deserts that plague underserved areas are also the result of anticompetitive strategies employed by both rural and urban hospitals. These strategies, which include mergers with competitors and non-competes in the labor market, eliminate access to care for rural populations and aggravate the severe shortage of nurses and physicians rural communities experience. In other words, these strategies contribute to hospital deserts in rural America. How did we get here?

In general, hospitals often claim that they need to merge with their competitors to cut their costs and improve their quality. Yet several hospitals often acquire their closest competitors in rural areas just to remove them from the market and increase their market power both in the hospital services and the labor markets.

For this reason, after the merger is complete, the acquiring hospitals shut down the newly acquired ones. This buy-to-shutter strategy has had a devastating impact on the health of rural communities who desperately need treatment. For instance, data show that each time a rural hospital shuts its doors, the mortality rate of rural residents significantly increases.

Even in cases where hospital mergers do not lead to closures, they still reduce access to care for the most vulnerable Americans—lower income individuals and communities of color. For instance, a recent study indicates that post-merger, only 15% of the acquired hospitals continue to offer acute care services. Other studies show that after the merger is complete, the acquiring hospitals often move to close essential healthcare services, such as maternal, primary, and surgical care.

When emergency departments in underserved areas shut down, the mental health of rural Americans deteriorates at dangerous rates. For rural Americans who lack coverage, entering a hospital’s emergency department is the only way they can gain access to acute mental healthcare services and substance abuse treatment. Not surprisingly, studies reveal that over the past two decades, the suicide rates for rural Americans have been consistently higher than for urban Americans.

But this is not the only reason why mergers among hospitals in rural areas contribute to the hospital closure crisis. Mergers also allow hospitals to increase their market power in input markets, most notably labor markets, and even attain monopsony power, especially if they operate in rural areas where competition in the hospital industry is limited.

This allows hospitals to suppress the wages of their employees and to offer them employment under unfavorable working conditions and employments terms, including non-competes. This exacerbates the severe shortage of nurses and physicians that rural hospitals are experiencing and, ultimately, contributes to their closures.

Empirical research validates these concerns. A recent study that assessed the relationship between concentration in the hospital industry and the wages of nurses in America reveals that mergers that considerably increased concentration in the hospital market slowed the growth of wages for nurses. Other surveys show that post-merger nurses and physicians experience higher levels of burnout and job dissatisfaction, as well as a heavier workload.

These toxic working conditions become almost inescapable when combined with non-compete clauses. By reducing job mobility, non-competes undermine employers’ incentives to improve the wages and the working conditions of their employees. Sound empirical studies illustrate that these risks are real. For instance, a leading study measuring the relationship between non-competes and wages in the U.S. labor market concludes that decreasing the enforceability of non-competes could increase the average wages for workers by more than 3%. Other surveys reveal that non-competes in the healthcare industry contribute to nurses’ and physicians’ burnout, encouraging them either to leave the market or seek early retirement at increasing rates. This premature exit also exacerbates the shortage of nurses and physicians that is hitting rural America.

Moreover, by eliminating job mobility, non-competes imposed by rural hospitals prevent nurses and physicians from offering their services in competing hospitals in underserved areas, which already struggle to attract workers in the healthcare industry and meet the increased needs of their patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated this problem. When, in the midst of the pandemic, there was a surge of COVID patients, many hospitals lacked the necessary medical staff to meet the demand. For this reason, several hospitals were forced to send patients with severe symptoms back home, leaving them without essential care. This likely contributed to the high mortality rates rural America experienced during the COVID 19 pandemic.

Given these risks, my article asks: Can antitrust law cure the hospital desert problem that harms the health and well-being of rural residents? It makes three proposals.

Proposal 1: Courts should examine all non-competes in the healthcare sector as per se violations of section 1 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits any unreasonable restraints of trade.

Per se illegal agreements are those agreements under antitrust law which are so harmful to competition and consumers that they are unlikely to produce any significant procompetitive benefits. Agreements not condemned as illegal per se are examined under the rule-of-reason legal test, a balancing test that the courts apply to weigh an agreement’s procompetitive benefits against the harm caused to competition. When applying the rule-of-reason test, courts generally follow a “burden-shifting approach.” First, the plaintiff must show the agreement’s main anticompetitive effects. Next, if the plaintiff meets its initial burden, the defendants must show that the agreement under scrutiny also produces some procompetitive benefits. Finally, if the defendant meet its own burden, the plaintiff must show that the defendant’s objectives can be achieved through less restrictive means.

To date, courts have examined all non-compete agreements in labor markets under the rule-of-reason test on the basis that they have the potential to create some procompetitive benefits. For instance, reduced mobility might benefit employers to the extent it allows them to recover the costs of training their workers and reduces the purported “free riding” that may occur if a new employer exploits the investment of the former employer.

Applying the rule-of-reason test in the case of non-competes, especially in the healthcare industry, is a mistake for at least two reasons. First, because hospitals do not appreciably invest in their workers’ education and training, there is little risk of such investment being appropriated. Hence, the claim that non-competes reduce the free riding off non-existent investment is simply unconvincing.

Second, because the rule-of-reason legal test is an extremely complex legal and economic test, the elevated standard of proof naturally benefits well-heeled defendants. This prevents nurses and physicians from challenging unreasonable non-competes, which ultimately encourages their employers to expand their use, even in cases where they lack any legitimate business interest to impose them.

Importantly, the federal agencies tasked with enforcing the antitrust laws, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), have not shut their ears to these concerns. Specifically, the FTC has proposed a new federal regulation that aims to ban all non-compete agreements across America, including those for physicians and nurses. Considering the severe harm non-competes in the healthcare sector cause to nurses, physicians, patients, and ultimately public health, this is a welcome development.

Proposal 2: Antitrust enforcers and the courts should start assessing the impact of hospital mergers on healthcare workers’ wages and working conditions

My article also argues that hospital mergers should be assessed with workers’ welfare at top of mind. Failing to do so will exacerbate the problem of hospital deserts, which so profoundly harms the lives and opportunities for millions of Americans. As noted, mergers allow hospitals to further increase their market power in the labor market. The removal of outside work options allows hospitals to suppress their workers’ wages and to offer employment under unfavorable terms, including non-competes. This encourages nurses and physicians to leave the market at ever increasing rates, which magnifies the severe shortage of nurses and physicians hospitals in rural communities are experiencing and contributes to their closures.

Despite these effects, thus far, whenever the enforcers assessed how a hospital merger may affect competition, they mainly focused on how the merger impacted the prices and the quality of hospital services. So how would the enforcers assess a hospital merger’s impact on labor?

First, enforcers would have to define the relevant labor market in which the anticompetitive effects—namely, suppressed wages and inferior working conditions—are likely to be felt. Second, enforcers would have to assess how the proposed merger may impact the levels of concentration in the labor industry. If the enforcers showed that the proposed merger would substantially increase concentration in the labor market, they would have good reason to stop the merger.

In response to such a showing, the merging hospitals might claim that the merger would create some important procompetitive benefits that may offset any harm to competition caused in the labor market. For instance, the hospitals may claim that the merger would allow hospitals to reduce the cost of labor and, hence, the rates they charge health insurers. This would benefit the purchasers of health insurance services, notably the employers and consumers. But should the courts be convinced by such a claim of offsetting benefits?

Not under the Supreme Court’s ruling in Philadelphia National Bank. There, the Supreme Court made clear that the procompetitive justifications in one market cannot outweigh its anticompetitive effects in another. For this reason, the courts could argue that any benefits the merger may create for one group of consumers—the purchasers of health insurance services—cannot outweigh any losses incurred by another group, the workers in the healthcare industry.

Proposal 3: Antitrust enforcers should accept hospital mergers in rural areas only under specific conditions

My article contends that such mergers should be condoned only under the most stringent of circumstances. Specifically, enforcers should accept mergers in rural areas only under the condition that the merged entity agrees to not shut down facilities or cut essential healthcare services in underserved areas.

Conclusion

Has antitrust law failed workers in the healthcare industry and ultimately public health? Given the concerns expressed above, the answer is unfortunately, yes. By failing to assess the impact of hospital mergers on the wages and the working conditions of employees in the hospital industry, and by examining all non-competes in labor markets under the rule-of-reason legal test, the courts have contributed to the hospital desert problem that disproportionately affects vulnerable Americans. If they fail to confront this crisis, the courts also risk contributing to the racial and health disparities that undermine the moral, social, and economic fabric in America.

Theodosia Stavroulaki is an Assistant Professor of Law at Gonzaga University School of law. Her teaching and research interests include antitrust, health law, and law and inequality. This piece draws on her article “The Healing Power of Antitrust” forthcoming in Northwestern University Law Review 119(4) (2025)