Your intrepid writer, when not toiling for free in the basement of The Sling, does a fair amount of testifying as an expert economic witness. Many of these cases involve alleged price-fixing (or wage-fixing) conspiracies. One would think there would be no need to define the relevant market in such cases, as the law condemns price-fixing under the per se standard. But because of certain legal niceties—such as whether the scheme involved an intermediary (or ringleader) that allegedly coached and coaxed the parties with price-setting power—we often spend reams of paper and hundreds of billable hours engaging in what amounts to navel inspection to determine the contours of the relevant market. The idea is that if the defendants do not collectively possess market power in a relevant antitrust market, then the challenged conduct cannot possibly generate anticompetitive effects.

A traditional method of defining the relevant market asks the following question: Could a hypothetical monopolist who controlled the supply of the good (or services) that allegedly comprise the relevant market profitably raise prices over competitive levels? The test has been shortened to the hypothetical monopolist test (HMT).

It bears noting that there are other ways to define relevant markets, including by assessing the Brown Shoe factors or practical indicia of the market boundaries. The Brown Shoe test can be used independently or in conjunction with the HMT. But this alternative is beyond the scope of this essay.

Published in the Harvard Law Review in 2010, Louis Kaplow’s essay was provocatively titled “Why (Ever) Define Markets”? It’s a great question, and having spent 25-odd years in the antitrust business, I can provide a smart-alecky and jaded answer: The market definition exercise is a way for defendants to deflect attention away from the harms inflicted on consumers (or workers) and towards an academic exercise, which is admittedly entertaining for antitrust nerds. Don’t look at the body on the ground, with goo spewing out of the victim’s forehead. Focus instead on this shiny object over here!

And it works. The HMT commands undue influence in antitrust cases, with some courts employing the market-definition exercise as a make-or-break evidentiary criterion for plaintiffs, before considering anticompetitive effects. Other classic examples of market definition serving as a distraction include American Express (2018), where the Supreme Court even acknowledged evidence a net price increase yet got hung up over market definition, or Sabre/Farelogic (2020), where the court acknowledged that the merging parties competed in practice but not per the theory of two-sided markets.

A better way forward

When it comes to retrospective monopolization cases (aka “conduct” cases), there is a more probative question to be answered. Rather than focusing on hypotheticals, courts should be asking whether a not-so-hypothetical monopolist—or collection of defendants that could mimic monopoly behavior—could profitably raise price above competitive levels by virtue of the scheme. Or in a monopsony case, did the not-so-hypothetical monopsonist—or collection of defendants assembled here—profitably reduce wages below competitive levels by virtue of the scheme? Let’s call this alternative the NSHMT, as we can’t compete against the HMT without our own clever acronym.

Consider this fact pattern. A ringleader, who gathered and then shared competitively sensitive information from horizontal rivals, has been accused of orchestrating a scheme to raise prices in a given industry. After years of engaging in the scheme, an antitrust authority began investigating, and the ring was disbanded. On behalf of plaintiffs, an economist builds an econometric model that links the prices paid to the customers at issue—typically a dummy variable equal to one when the defendant was part of the scheme and zero otherwise—plus a host of control variables that also explain movements in prices. After controlling for many relevant (i.e., motivated by record evidence or economic theory) and measurable confounding factors, eliminating any variables that might serve as mediators of the scheme itself, the econometric model shows that the scheme had an economically and statistically significantly effect of artificially raising prices.

Setting aside any quibbles that defendants’ economists might have with the model—it is their job to quibble over modeling choices while accepting that the challenged conduct occurred—the clear inference is that this collection of defendants was in fact able to raise prices while coordinating their affairs through the scheme. Importantly, they could not have achieved such an outcome of inflated prices unless they collectively possessed selling power. (Indeed, why would defendants engage in the scheme in the first place, risking antitrust liability, if higher profits could not be achieved?) So, if we are trying to assemble the smallest collection of products such that a (not-so) hypothetical seller of such products could exercise selling power, we have our answer! The NSHMT is satisfied, which should end the inquiry over market power.

(Note that fringe firms in the same industry might weakly impose some discipline on the collection of firms in the hypothetical. But the fringe firms were apparently not needed to exercise power. Hence, defining the market slightly more broadly to include the fringe is a conservative adjustment.)

At this point, the marginal utility of performing a formal HMT to define the relevant market based on what some hypothetical monopolist could pull off is dubious. I use the modifier “formal” to connote a quantitative test as to whether a hypothetical monopolist who controlled the purported relevant market could increase prices by (say) five percent above competitive levels.

The formal HMT has a few variants, but a standard formulation proceeds as follows. Step 1: Measure the actual elasticity of demand faced by defendants. Step 2: Estimate the critical elasticity of demand, which is the elasticity that would make the hypothetical monopolist just indifferent between raising and not raising prices. Step 3: Compare the actual to the critical elasticity; if the former is less than the latter, then the HMT is satisfied and you have yourself a relevant antitrust market! An analogous test compares the “predicted loss” to the “critical loss” of a hypothetical monopolist.

For those thinking the New Brandeisians dispensed with such formalism in the newly issued 2023 Merger Guidelines, I refer you to Section 4.3.C, which spells out the formal HMT in “Evidence and Tools for Carrying Out the Hypothetical Monopoly Test.” To their credit, however, the drafters of the new guidelines relegated the formal HMT to the fourth of four types of tools that can be used to assess market power. See Preamble to 4.3 at pages 40 to 41, placing the formal HMT beneath (1) direct evidence of competition between the merging parties, (2) direct evidence of the exercise of market power, and (3) the Brown Shoe factors. It bears noting that the Merger Guidelines were designed with assessing the competitive effects of a merger, which is necessarily a prospective endeavor. In these matters, the formal HMT arguably can play a bigger role.

Aside from generating lots of billable hours for economic consultants, the formal HMT in retrospective conduct cases bears little fruit because the test is often hard to implement and because the test is contaminated by the scheme itself. Regarding implementation, estimating demand elasticities—typically via a regression on units sold—is challenging because the key independent variable (price) in the regression is endogenous, which when not correctly may lead to biased estimates, and therefore requires the economist to identify instrumental variables that can stand in the shoes of prices. Fighting over the proper instruments in a potentially irrelevant thought experiment is the opposite of efficiency! Regarding the contamination of the formal test, we are all familiar with the Cellophane fallacy, which teaches that at elevated prices (owing to the anticompetitive scheme), distant substitutes will appear closer to the services in question, leading to inflated estimates of the actual elasticity of demand. Moreover, the formal HMT is a mechanical exercise that may not apply to all industries, particularly those that do not hold short-term profit maximization as their objective function.

The really interesting question is, What happens if the NSHMT finds an anticompetitive effect owing to the scheme—and hence an inference of market power—but the formal HMT finds a broader market is needed? Clearly the formal HMT would be wrong in that instance for any (or all) of the myriad reasons provided above, and it should be given zero weight by the factfinder.

A special form of direct proof

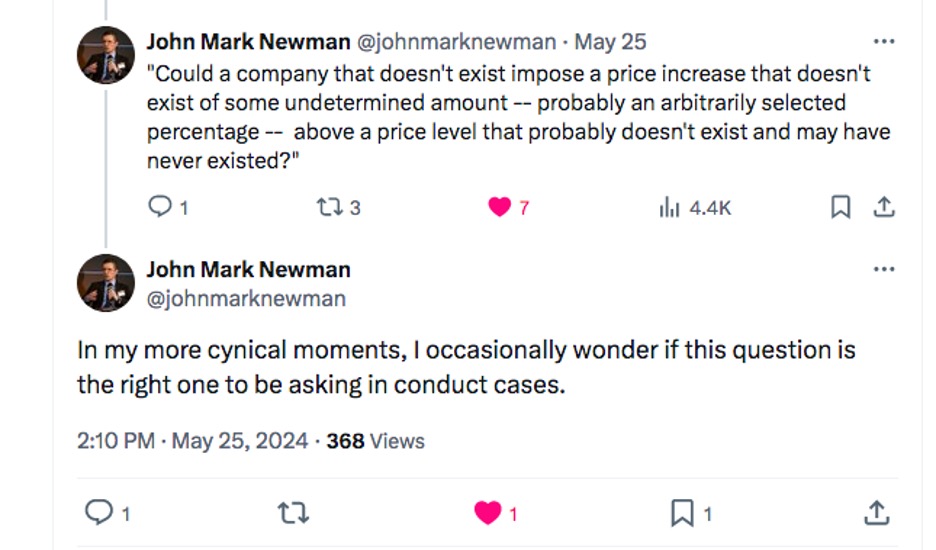

An astute reader might recognize the NSHMT as a type of direct proof of market power, which has been recognized as superior to indirect proof of market power—that is, showing high shares and entry barriers in a relevant market. As explained by Carl Shapiro, former Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Economics at DOJ: “IO economists know that the actual economic effects of a practice do not turn on where one draws market boundaries. I have been involved in many antitrust cases where a great deal of time was spent debating arcane details of market definition, distracting from the real economic issues in the case. I shudder to think about how much brain damage among antitrust lawyers and economists has been caused by arguing over market definition.” Aaron S. Edlin and Daniel L. Rubinfeld offered this endorsement of direct proof: “Market definition is only a traditional means to the end of determining whether power over price exists. Power over price is what matters . . . if power can be shown directly, there is no need for market definition: the value of market definition is in cases where power cannot be shown directly and must be inferred from sufficiently high market share in a relevant market.” More recently, John Newman, former Deputy Director of the Bureau of Competition at the FTC, remarked on Twitter: “Could a company that doesn’t exist impose a price increase that doesn’t exist of some undetermined amount—probably an arbitrarily selected percentage—above a price level that probably doesn’t exist and may have never existed? In my more cynical moments, I occasionally wonder if this question is the right one to be asking in conduct cases.”

I certainly agree with these antitrust titans that direct proof of power is superior to indirect proof. Let me humbly suggest that the NSHMT is distinct from and superior to common forms of direct proof. Common forms of direct proof include evidence that the defendant commands a pricing premium over its peers (or imposes a large markup), as determined by some competitive benchmark (or measure of incremental costs), or engages in price discrimination, which is only possible if it faces a downward-sloping demand curve. The NSHMT is distinct from these common forms of direct evidence because it is tethered to the challenged conduct. It is superior to these other forms because it addresses the profitability of an actual price increase owing to the scheme as opposed to levels of arguably inflated prices. Put differently, it is one thing to observe that a defendant is gouging customers or exploiting its workers. It is quite another to connect this exploitation to the scheme itself.

Regarding policy implications, when the NSMHT is satisfied, there should be no need to show market power indirectly via the market-definition exercise. To the extent that market definition is still required, when there is a clear case of the scheme causing inflated prices or lower output or exclusion in monopolization cases, plaintiffs should get a presumption that defendants possess market power in a relevant market.

In summary, for merger cases, where the analysis focuses on a prospective exercise of power, the HMT might play a more useful role. In merger cases, we are trying to predict the profitability of some future price increase. Even in merger cases, the economist might be able to exploit price increases (or wage suppression) owing to prior acquisitions, which would be a form of direct proof. For conduct cases, however, the NSHMT is superior to the HMT, which offers little marginal utility for the factfinder. The NSHMT just so happens to inform the profitability of an actual price hike by a collection of actual firms that wield monopoly power, as opposed to some hypothetical monopolist. And it also helpfully focuses attention on the anticompetitive harm, where it rightly belongs. Look at the body on the ground and not at the shiny object.

America’s working people and their elected representatives in the labor movement have been an untapped resource for antitrust enforcers. That should change. Not only are workers an underutilized source of information about the likely effects of a merger, but their labor organizations also offer an effective counter to employer power.

As signaled with the Executive Order on Promoting Competition issued in July 2021, the Biden administration has adopted a new approach to competition policy. The agencies have rhetorically defenestrated the previously hegemonic consumer-welfare standard, which held that low consumer prices and high output are the sole and sacrosanct goals of antitrust, to the exclusion of other aims set out by Congress, such as regulating competition to protect democracy and to preserve economic liberty. Consistent with the agencies’ charge from Congress, the Executive Order includes the protection of workers from employers’ power and unfair practices—economic liberty includes the freedom from exploitation.

Moreover, the agencies have welcomed the broader public into the heretofore esoteric and rarified domain of antitrust, where arid theories have long taken precedence over effects of corporate practices on human beings. For example, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) now holds regular meetings that are open to the public, and the Department of Justice (DOJ) and FTC have solicited public comments on antitrust and competition regulations and policy documents from groups well outside the usual suspects in academia and the antitrust bar.

We’d like to focus here on one group in particular that has embraced the invitation to join the antitrust discussion: the labor movement. As it turns out, working people and their elected representatives in labor unions have a lot to say about competition policy. And as an antitrust economist and lawyer, we believe our community should listen carefully. In their public comments on the draft Merger Guidelines, labor unions have articulated a holistic approach to monopoly power that moves beyond the narrow recent obsession with consumer welfare and returns to the aims of Congress. For example, as the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) wrote in its comments, “[e]conomic concentration enables political concentration, which in turn corrodes democracy.” This echoes the concerns of the authors of the antitrust laws: the Supreme Court once described the Sherman Act as “a comprehensive charter of economic liberty.”

We’d like to highlight three themes emerging from the comments submitted by labor unions that speak powerfully to break with antitrust law’s recent friendliness to big business and return to the meaning of the statutes enacted by Congress. First, unions emphasize the need to treat workers and their unions as the expert market participants they are, with an immense store of untapped knowledge and experience to offer agencies throughout the merger review process. For example, SEIU’s comment contained several examples of harms from market power and mergers spoken directly by healthcare workers, who called on the agencies to include workers and representatives when they conduct merger reviews. While the antitrust agencies have sometimes informally consulted workers during merger reviews, unions have asked that this engagement be deepened and formalized. The Communication Workers of America (CWA) thus applauded the agencies for “mak[ing] explicit what has been an occasional, informal practice of consulting with labor unions,” pointing out that “workers’ deep knowledge of their industry is an invaluable input into the review process.”

Indeed, they are: Workers are deeply informed and have a unique perspective, not only on labor market matters, but on product markets and industry conditions as well. Workers are most likely to know “where the bodies are buried” in any given transaction, and thus represent a previously untapped source of rich qualitative and quantitative information on industrial and market conditions. They should be brought into the merger process and given a central role in a process long dominated by lawyers and economists with little relevant industry knowledge.

Second, comments from labor unions stressed the necessity of returning to the statutes by embracing strong structural presumptions against mergers tied to market share. CWA called for the use of market share tests instead of the “judicial fortune telling” that has prevailed for decades. The Strategic Organizing Center (SOC), a coalition of several labor unions including CWA and the SEIU, encouraged the agencies to lower the structural presumptions in the final guidelines. As part of this, they emphasized the need for the agencies to not weigh purported benefits to consumers as offsetting harms to workers—especially the practice of treating harms to workers as cost-saving “efficiencies” that putatively justify mergers that may lessen competition.

For example, SEIU noted that HCA, a major hospital chain, typically lowered staffing levels after acquiring a hospital. SEIU argued, correctly in our view, that while layoffs and lower staffing levels in healthcare may boost profitability, they should not be considered a benefit from mergers. CWA, for its part, called for a return to the plain language of the statute and controlling Supreme Court case law, which proscribe balancing out-of-market benefits against harms to other market participants, such as workers, in a relevant antitrust market. Meanwhile the AFL-CIO, the major labor federation in the United States, commented that proposed merger “efficiencies” have sometimes included layoffs that “fatten the bottom line” at the expense of workers and product quality. Urging the two agencies to go further than they did in the draft Merger Guidelines, the labor federation, relying on binding Supreme Court precedent, called on the DOJ and the FTC to explicitly reject an efficiencies defense for presumptively illegal mergers.

Third, labor comments importantly reminded the antitrust agencies of the inherent power imbalance in the employer-employee relationship. Given the unequal distribution of property and the necessity for most people to either work or starve, the 19th century labor republican George McNeill wrote workers “assent but they do not consent, they submit but they do not agree.” In addition to the monopsony power stemming from employer concentration, the challenges of finding new work, and workers’ preferences for certain types of work and work environments highlighted by antitrust economists, virtually all workers are subject to employer power, embodied by take-it-or-leave-it employment terms and at-will employment.

Employer power is the rule in labor markets, not the exception. Labor, employment, and antitrust law have long recognized this basic fact, creating legal protections for workers, including the antitrust exemption for collective action, and providing the formal structure of collective bargaining to counteract employers’ wage-setting power.

And yet, as the AFL-CIO’s comments pointed out, “unions, collective bargaining and collective bargaining agreements are not explicitly mentioned” in the draft Merger Guidelines. This is an important oversight because, as the AFL-CIO points out, “unions and collective bargaining can provide a counterbalance to the effects of a merger on workers.” CWA went further, arguing that this omission risked continuing the “misguided trend of interpreting the employment relationship as based in individual contract, rather than being structured by labor market institutions.” The SOC urged the agencies to “to recognize collective bargaining as a structural remedy to concentrated corporate power.” Collectively bargained wages are no longer unilaterally set by employers but negotiated under threat of strike or alternative means like arbitration. Thus, unions and collective bargaining are an available remedy to employer monopsony power in labor markets. (While more likely to litigate troubling consolidations than they were in the past, the antitrust agencies continue to accept remedies in merger cases.) The positive effect of collective bargaining likely extends beyond the workers directly covered by the agreement: there is evidence of spillovers from collectively bargained wages to workers not covered by the agreement.

One area of policy disagreement: some of the labor comments encouraged the agencies to rely on certain practices as indicators of “market power.” These include the use of particular contractual restraints on workers and misclassifying employees as independent contractors. We agree that these practices are harmful, but believe that they are best addressed, not by implicitly tolerating such conduct and incorporating them into merger review, but by agency action to directly prohibit them. In particular, the FTC, with its expansive statutory authorities, should directly restrict these practices. For instance, the FTC should challenge the misclassification of workers as an “unfair method of competition.” As we have written elsewhere, we believe antitrust regulators can help workers most by challenging unfair business practices and models.

Brian Callaci is Chief Economist at Open Markets Institute. Sandeep Vaheesan is Legal Director at Open Markets Institute.

If I were to draft new Merger Guidelines, I’d begin with two questions: (1) What have been the biggest failures of merger enforcement since the 1982 revision to the Merger Guidelines?; and (2) What can we do to prevent such failures going forward? The costs of under-enforcement have been large and well-documented, and include but are not limited to higher prices, less innovation, lower quality, greater inequality, and worker harms. It’s high time for a course correction. But do the new Merger Guidelines, promulgated by Biden’s Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC), do the trick?

Two Recent Case Studies Reveal the Problem

Identifying specific errors in prior merger decisions can inform whether the new Guidelines will make a difference. Would the Guidelines have prevented such errors? I focus on two recent merger decisions, revealing three significant errors in each for a total of six errors.

The 2020 approval of the T-Mobile/Sprint merger—a four-to-three merger in a highly concentrated industry—was the nadir in the history of merger enforcement. Several competition economists, myself included, sensed something was broken. Observers who watched the proceedings and read the opinion could fairly ask: If this blatantly anticompetitive merger can’t be stopped under merger law and the existing Merger Guidelines, what kind of merger can be stopped? Only mergers to monopoly?

The district court hearing the States’ challenge to T-Mobile/Sprint committed at least three fundamental errors. (The States had to challenge the merger without Trump’s DOJ, which embraced the merger for dubious reasons beyond the scope of this essay.) First, the court gave undue weight to the self-serving testimony of John Legere, T-Mobile’s CEO, who claimed economies from combining spectrum with Sprint, and also claimed that it was not in T-Mobile’s nature to exploit newfound market power. For example, the opinion noted that “Legere testified that while T-Mobile will deploy 5G across its low-band spectrum, that could not compare to the ability to provide 5G service to more consumers nationwide at faster speeds across the mid-band spectrum as well.” (citing Transcript 930:23-931:14). The opinion also noted that:

T-Mobile has built its identity and business strategy on insulting, antagonizing, and otherwise challenging AT&T and Verizon to offer pro-consumer packages and lower pricing, and the Court finds it highly unlikely that New T-Mobile will simply rest satisfied with its increased market share after the intense regulatory and public scrutiny of this transaction. As Legere and other T-Mobile executives noted at trial, doing so would essentially repudiate T-Mobile’s entire public image. (emphasis added) (citing Transcript at 1019:18-1020:1)

In the court’s mind, the conflicting testimony of the opposing economists cancelled each other out—never mind such “cancelling” happens quite frequently—leaving only the CEO’s self-serving testimony as critical evidence regarding the likely price effects. (The States’ economic experts were the esteemed Carl Shapiro and Fiona Scott Morton.) It bears noting that CEOs and other corporate executives stand to benefit handsomely from the consummation of a merger. For example, Activision Blizzard Inc. CEO Bobby Kotick reportedly stands to reap more than $500 million after Microsoft completes its purchase of the video game publishing giant.

Second, although the primary theory of harm in T-Mobile/Sprint was that the merger would reduce competition for price-sensitive customers of prepaid service, most of whom live in urban areas, the court improperly credited speculative commitments to “provide 5G service to 85 percent of the United States rural population within three years.” Such purported benefits to a different set of customers cannot serve as an offset to the harms to urban consumers who benefited from competition between the only two facilities-based carriers that catered to prepaid customers.

Third, the court improperly embraced T-Mobile’s proposed remedy to lease access to Dish at fixed rates—a form of synthetic competition—to restore the loss in facilities-based competition. Within months of the consummated merger, the cellular CPI ticked upward for the first time in a decade (save a brief blip in 2016), and T-Mobile abandoned its commitments to Dish.

The combination of T-Mobile/Sprint represented the elimination of actual competition across two wireless providers. In contrast, Facebook’s acquisition of Within, maker of the most popular virtual reality (VR) fitness app on Facebook’s VR platform, represented the elimination of potential competition, to the extent that Facebook would have entered the VR fitness space (“de novo entry”) absent the acquisition. In disclosure, I was the FTC’s economic expert. (I commend everyone to read the critical review of the new Merger Guidelines by Dennis Carlton, Facebook’s expert, in ProMarket, as well as my thread in response.) The district court sided with the FTC on (1) the key legal question of whether potential competition was a dead letter (it is not), (2) market definition (VR fitness apps), and (3) market concentration (dominated by Within). Yet many observers strangely cite this case as an example of the FTC bringing the wrong cases.

Alas, the court did not side with the FTC on the key question of whether Facebook would have entered the market for VR fitness apps de novo absent the acquisition. To arrive at that decision, the court made three significant errors. First, as Professor Steve Salop has pointed out, the court applied the wrong evidentiary standard for assessing the probability of de novo entry, requiring the FTC to show a probability of de novo entry in excess of 50 percent. Per Salop, “This standard for potential entry substantially exceeds the usual Section 7 evidentiary burden for horizontal mergers, where ‘reasonable probability’ is normally treated as a probability lower than more-likely-than-not.” (emphasis in original)

Second, the court committed an error of statistical logic, by crediting the lack of internal deliberations in the two months leading up to Facebook’s acquisition announcement in June 2021 as evidence that Facebook was not serious about de novo entry. Three months before the announcement, however, Facebook was seriously considering a partnership with Peloton—the plan was approved at the highest ranks within the firm. Facebook believed VR fitness was the key to expanding its user base beyond young males, and Facebook had entered several app categories on its VR platform in the past with considerable success. Because de novo entry and acquisition are two mutually exclusive entry paths, it stands to reason that conditional on deciding to enter via acquisition, one would expect to see a cessation of internal deliberation on an alternative entry strategy. After all, an individual standing at a crossroads would consider alternative paths, but upon deciding which path to take and embarking upon it, the previous alternatives become irrelevant. Indeed, the opinion even quoted Rade Stojsavljevic, who manages Facebook’s in-house VR app developer studios, testifying that “his enthusiasm for the Beat Saber–Peloton proposal had “slowed down” before Meta’s decision to acquire Within,” indicating that the decision to pursue de novo entry was intertwined with the decision to entry via acquisition. In any event, the relevant probability for this potential competition case was the probability that Facebook would have entered de novo in the absence of the acquisition. And that relevant probability was extremely high.

Third, like the court in T-Mobile/Sprint, the district court again credited the self-serving testimony of Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, who claimed that he never intended to enter VR fitness apps de novo. For example, the court cited Mr. Zuckerberg’s testimony that “Meta’s background and emphasis has been on communication and social VR apps,” as opposed to VR fitness apps. (citing Hearing Transcript at 1273:15–1274:22). The opinion also credited the testimony of Mr. Stojsavljevic for the proposition that “Meta has acquired other VR developers where the experience requires content creation from the developer, such as VR video games, as opposed to an app that hosts content created by others.” (citing Hearing Transcript at 87:5–88:2). Because this error overlaps with one of the three errors identified in the T-Mobile/Spring merger, I have identified five distinct errors (six less one) needing correction by the new Merger Guidelines.

Although the court credited my opinion over Facebook’s experts on the question of market definition and market concentration, the opinion did not cite any economic testimony (mine or Facebook’s experts) on how to think about the probability of entry absent the acquisition.

The New Merger Guidelines

I raise these cases and their associated errors because I want to understand whether the new Merger Guidelines—thirteen guidelines to be precise—will offer the kind of guidance that would prevent a future court from repeating the same (or similar) errors. In particular, would either the T-Mobile/Sprint or Facebook/Within decision (or both) have been altered in any significant way? Let’s dig in!

The New Guidelines reestablish the importance of concentration in merger analysis. The 1982 Guidelines, by contrast, sought to shift the emphasis from concentration to price effects and other metrics of consumer welfare, reflecting the Chicago School’s assault on the structural presumption that undergirded antitrust law. For several decades prior to the 1980s, economists empirically studied the effect of concentration on prices. But as the consumer welfare standard became antitrust’s north star, such inquiries were suddenly considered off-limits, because concentration was deemed to be “endogenous” (or determined by the same factors that determine prices), and thus causal inferences of concentration’s effect on price were deemed impossible. This was all very convenient for merger parties.

Guideline One states that “Mergers Should Not Significantly Increase Concentration in Highly Concentrated Markets.” Guideline Four states that “Mergers Should Not Eliminate a Potential Entrant in a Concentrated Market,” and Guideline Eight states that “Mergers Should Not Further a Trend Toward Concentration.” By placing the word “concentration” in three of thirteen principles, the agencies make it clear that they are resuscitating the prior structural presumption. And that’s a good thing: It means that merger parties will have to overcome the presumption that a merger in a concentrated or concentrating industry is anticompetitive. Even Guideline Six, which concerns vertical mergers, implicates concentration, as “foreclosure shares,” which are bound from above by the merging firms’ market share, are deemed “a sufficient basis to conclude that the effect of the merger may be to substantially lessen competition, subject to any rebuttal evidence.” The new Guidelines restore the original threshold Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of 1,800 and delta HHI of 100 to trigger the structural presumption; that threshold had been raised to an HHI of 2,500 and a change in HHI of 200 in the 2010 revision to the Guidelines.

This resuscitation of the structural presumption is certainly helpful, but it’s not clear how it would prevent courts from (1) crediting self-serving CEO testimony, (2) embracing bogus efficiency defenses, (3) condoning prophylactic remedies, (4) committing errors in statistical logic, or (5) applying the wrong evidentiary standard for potential competition cases.

Regarding the proper weighting of self-serving employee testimony, error (1), Appendix 1 of the New Guidelines, titled “Sources of Evidence,” offers the following guidance to courts:

Across all of these categories, evidence created in the normal course of business is more probative than evidence created after the company began anticipating a merger review. Similarly, the Agencies give less weight to predictions by the parties or their employees, whether in the ordinary course of business or in anticipation of litigation, offered to allay competition concerns. Where the testimony of outcome-interested merging party employees contradicts ordinary course business records, the Agencies typically give greater weight to the business records. (emphasis added)

If heeded by judges, this advice should limit the type of errors we observed in T-Mobile/Sprint and Facebook/Within, with courts crediting the self-serving testimony by CEOs and other high-ranking employees.

Regarding the embrace of out-of-market efficiencies, error (2), Part IV.3 of the New Guidelines, in a section titled “Procompetitive Efficiencies,” offers this guidance to courts:

Merging parties sometimes raise a rebuttal argument that, notwithstanding other evidence that competition may be lessened, evidence of procompetitive efficiencies shows that no substantial lessening of competition is in fact threatened by the merger. When assessing this argument, the Agencies will not credit vague or speculative claims, nor will they credit benefits outside the relevant market. (citing Miss. River Corp. v. FTC, 454 F.2d 1083, 1089 (8th Cir. 1972)) (emphasis added)

Had this advice been heeded, the court in T-Mobile/Sprint would have been foreclosed from crediting any purported merger-induced benefits to rural customers as an offset to the loss of competition in the sale of prepaid service to urban customers.

Regarding the proper treatment of prophylactic remedies offered by merger parties, error (3), footnote 21 of the New Guidelines state that:

These Guidelines pertain only to the consideration of whether a merger or acquisition is illegal. The consideration of remedies appropriate for otherwise illegal mergers and acquisitions is beyond its scope. The Agencies review proposals to revise a merger in order to alleviate competitive concerns consistent with applicable law regarding remedies. (emphasis added)

While this approach is very principled, the agencies cannot hope to cure a current defect by sitting on the sidelines. I would advise saying something explicit about remedies, including mentioning the history of their failures to restore competition, as Professor John Kwoka documented so ably in his book Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies (MIT Press 2016).

Finally, regarding courts’ committing errors in statistical logic or applying the wrong evidentiary standard for potential competition cases, errors (4) and (5), the New Merger Guidelines devote an entire guideline (Guideline Four) to potential competition. Guideline Four states that “the Agencies examine (1) whether one or both of the merging firms had a reasonable probability of entering the relevant market other than through an anticompetitive merger.” Unfortunately, there is no mention that reasonable probability can be satisfied at less than 50 percent, per Salop, and the agencies would be wise to add such language in the Merger Guidelines. In defining “reasonable probability,” the Guidelines state that evidence that “the firm has successfully expanded into other markets in the past or already participates in adjacent or related markets” constitutes “relevant objective evidence” of a reasonable probably. In making its probability assessment, the court in Facebook/Within did not credit Facebook’s prior de novo entry in other app categories on Facebook’s VR platform. The Guidelines also state that “Subjective evidence that the company considered organic entry as an alternative to merging generally suggests that, absent the merger, entry would be reasonably probable.” Had it heeded this advice, the court would have ignored, when assessing the probability of de novo entry absent the merger, the fact that Facebook did not mention the Peloton partnership two months prior to the announcement of its acquisition of Within.

A Much Needed Improvement

In summary, I conclude that the new Merger Guidelines offer precisely the kind of guidance that would have prevented the courts in T-Mobile/Sprint and in Facebook/Within from committing significant errors. The additional language suggested here—taking a firm stance on remedies and defining reasonable probability—is really fine-tuning. While this review is admittedly limited to these two recent cases, the same analysis could be undertaken with respect to a broader array of anticompetitive mergers that have approved by courts since the structural presumption came under attack in 1982. The agencies should be commended for their good work to restore the enforcement of antitrust law.

The New Merger Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) provide a framework for analyzing when proposed mergers likely violate Section 7 of the Clayton Act that is more faithful to controlling law and Congressional intent than earlier Guidelines. The thirteen guidelines presented in the new Guidelines go quite a long way in pulling the Agencies back from an approach that placed undue burden on plaintiffs and ignored important factors such as the trend in market concentration and serial mergers that were addressed by earlier Supreme Court precedent. The Guidelines also incorporate the modern, more objective economics of the post-Chicago school of economics. For these reasons, and others, the Guidelines should be applauded.

Unfortunately, remnants of Judge Bork’s Consumer Welfare Standard remain. In several places the Guidelines refer to a merger’s anticompetitive effects as price, quantity (output), product quality or variety, and innovation. These are all effects that can shift demand curves or equilibrium positions in the output market and thus increase consumer surplus, the only goal recognized by the Consumer Welfare Standard.

To their credit, the Guidelines also mention input markets, referring to mergers that decrease wages, lower benefits or cause working conditions to deteriorate. Lower wages reduce labor surplus (rent), a consideration that would come within a Total Trading Partner Surplus approach. However, the traditional goals of antitrust as articulated by Congress and many Supreme Court opinions, including protecting democracy through dispersion of economic and political power, protection of small business, and preventing unequal income and wealth distribution, are conspicuously absent.

The basis for these traditional goals is well known. Prominent economist Stephen Martin has documented the judicial and congressional statements concerning the antitrust goal of dispersion of power. The historical support for the goal of preserving small business can be found in a recent paper by two of the authors of this piece. Lina Khan and Sandeep Vaheesan, and Robert Lande and Sandeep Vaheesan, have laid out the textual support for the antitrust inequality goal. Moreover, welfare economists have empirically demonstrated significant positive welfare effects from democracy, small business formation, and income equality.

Indeed, the Brown Shoe opinion, on which the Guidelines heavily rely, examined whether the lower court opinion was “consistent with the intent of the legislature” which drafted the 1950 Amendments, and the opinion itself refers to the goal of “protection of small businesses” in at least two places. The legislative history of the 1950 Amendment deemed important by the Brown Shoe Court evinced a clear concern that rising concentration will, according to Senator O’Mahoney, “result in a terrific drive toward a totalitarian government.”

The remnants of the Consumer Welfare Standard are most evident in the Guidelines’ rebuttal section on efficiencies. The Guidelines open the section with the recognition that controlling precedent is clear that efficiencies are not a defense to a merger that violates Section 7; accordingly, the section is offered as a rebuttal rather than a defense. In essence, if the merging parties can identify merger-specific and verifiable efficiencies, it can rebut a finding that the merger substantially lessened competition. The Guidelines do not define “efficiencies.” However, the context makes clear that Guidelines mean to follow previous versions of the Merger Guidelines, that assume “efficiencies” are primarily cost savings. A defendant can offer a rebuttal to a presumption that a merger may significantly harm competition, if such cost savings are passed through to consumers in lower prices, to a degree that offsets any potential post-merger price increase. There are at least six reasons why the Agencies should jettison this “efficiency” rebuttal.

First, lower prices resulting from cost savings are quite a bit different than lower prices resulting from entry (rebuttal by entry). New entry reduces concentration, but cost savings at best will only lower output price, and higher prices (or reduced output) is not the sole problem that results from high concentration except under a strict Consumer Welfare Standard.

Second, to the extent the Guidelines equate efficiencies with cost savings (as in earlier merger guidelines), they have adopted the businessman’s definition of efficiencies. In contrast, economic theory suggests that some cost savings lower rather than raise social welfare. For example, cost savings from lower wages, greater unemployment, or redistribution between stakeholders can both lower welfare and reduce prices. An increase in consumer or producer surplus that comes at the expense of input supplier surplus can also lower welfare.

Third, only under the output-market half of a surplus theory of economic welfare, which is the original Consumer Welfare Standard, can one clearly link cost savings to economic welfare, because lower cost increases consumer and/or producer surplus. As we show elsewhere, this theory has been thoroughly discredited by welfare economists. In fact, for economists, “efficiency” only means Pareto efficiency. As discussed by Gregory Werden and by Mas-Colell et al.’s leading Microeconomics textbook (Chapter 10), the assumptions necessary to ensure that maximizing surplus results in Pareto Efficiency are extreme and unrealistic. These assumptions include quasilinear utility, perfectly competitive other markets, and lump sum wealth redistributions that maximize social welfare. This discredits the surplus approach, which is the only way to reconcile Pareto Efficiency, which is what efficiencies mean in economic theory, with cost savings, which is the definition implied in the Guidelines.

Fourth, the efficiency section is superfluous. As many economists have recognized, most recently Nancy Rose and Jonathan Sallet, the merging parties are already credited for efficiencies (cost savings) in the “standard efficiency credit” which undergirds Guideline 1. After all, absent any efficiencies, why allow any merger that evenly weakly increases concentration? A concentration screen that allows some mergers and not others must be assuming that all mergers come with some socially beneficial cost savings. Why do we need another rebuttal section when cost savings have already been credited?

Fifth, there is no empirical research to suggest that mergers that increase concentration actually lower costs and pass on sufficient benefits to consumers to constitute a successful rebuttal. As one district court commented, “The Court is not aware of any case, and Defendants have cited none, where the merging parties have successfully rebutted the government’s prima facia case on the strength of the efficiencies.” We have identified nine studies measuring either cost savings or productivity gains or profitability from mergers spanning industries like health insurance, banking, utility, manufacturing, beer, and concrete industries. Five of these studies find no evidence of productivity gain or a cost reduction. The other four studies find productivity gains in terms of cost savings; but three of these four studies report a significant increase in prices to the consumers post-merger, and the remaining study does not report price effects post-merger. In other words, we have not been able to find any empirical study showing post-merger pass on of cost savings to consumers. These results are consistent with those of Professor Kwoka, who performs a comprehensive meta-analysis of the price effects of horizontal mergers and finds that the post-merger price at the product-level increases by 7.2 percent on average, holding all other influences constant. More than 80 percent of product prices show increases, and those increases average 10.1 percent.

Sixth, even if there were cost savings from mergers it is unlikely that they would be merger- specific and verifiable. Earlier versions of the Merger Guidelines expressed skepticism that economies of scale or scope could not be achieved by internal expansion (1968 Merger Guidelines) or that cost savings related to “procurement, management or capital costs” would be merger specific (1997 Merger Guidelines). In their article on merger efficiencies, Fisher and Lande write that “it would be extremely difficult for merging firms to prove that they could not attain the anticipated efficiencies or quality improvements through internal expansion.” Louis Kaplow has argued that the ability to use contracting to achieve claimed efficiencies is seriously underappreciated or studied. Verification of future efficiencies is also inherently problematic. The 1997 Merger Guidelines state that efficiencies related to R&D are “less susceptible to verification.” This problem and other verification hurdles are discussed by Joe Brodley and John Kwoka. In summary, the New Merger Guidelines could be improved by a footnote in Guideline One clarifying the multiple antitrust goals Congress sought to achieve by preventing concentrated markets through mergers. In addition, the Agencies should take seriously the holdings of at least three Supreme Court Opinions, none of which have been overturned (Brown Shoe, Phila. Nat’l Bank and Procter & Gamble Co.) that (as quoted in the Guidelines) “possible economies [from a merger] cannot be used as a defense to illegality.” There are good reasons to abandon an efficiencies rebuttal as well.

Mark Glick, Pavitra Govindan and Gabriel A. Lozada are professors in the economics department at the University of Utah. Darren Bush is a professor in the law school at the University of Houston.

Over the last 40 years, antitrust cases have been increasingly onerous and costly to litigate, yet if plaintiffs can prevail on one single issue, they dramatically enhance their chances of obtaining a favorable judgment. That issue is market definition.

Market definition is straightforward to explain because it’s just what it sounds like. Litigants and judges must be able to delineate the market in question in order to determine how much control a corporation exercises over it. Defining a relevant market essentially answers, depending on the conduct courts are analyzing, whether computers that run Apple’s MacOS operating system or Microsoft Windows are in the same market or, similarly, if Coca-Cola competes with Pepsi.

A corporation’s degree of control over any particular market is then typically measured by how much market share it has. In antitrust litigation, calculating a firm’s market share is the simplest and most common way to determine a firm’s ability to adversely affect market competition, including its influence over output, prices, or the entry of new firms. While the issue may seem mundane and even somewhat technocratic, defining a relevant market is the single most important determination in antitrust litigation. Indeed, many antitrust violations turn on whether a defendant has a high market share in the relevant market.

Market definition is a throughline in antitrust litigation. All violations that require a rule of reason analysis under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, such as resale price maintenance and vertical territorial restraints, require a market to be defined. All claims under Section 2 of the Sherman Act require a relevant market. And all claims under Sections 3 and 7 of the Clayton Act require a relevant market to be defined.

Defining relevant markets stems from the language of the antitrust laws. Section 2 of the Sherman Act states that monopolization tactics are illegal in “any part of the trade or commerce[.]” Sections 3 and Section 7 prohibit exclusive deals and tyings involving commodities and mergers, respectively in “any line of commerce or…in any section of the country[.]” “[A]ny” “part” or “line of commerce” inherently requires some description of a market that is at issue.

As I more thoroughly described in a newly released working paper, the process of defining relevant markets has a long and winding history stemming from the inception of the Sherman Act in 1890. Between 1890 and 1944, the Supreme Court took a highly generalized approach, requiring as it stated in 1895, only a description of “some considerable portion, of a particular kind of merchandise or commodity[.]” In subsequent cases during this initial era, the Supreme Court provided little additional guidance, maintaining that litigants merely needed to provide a generalized description of “any one of the classes of things forming a part of interstate or foreign commerce.”

In 1945, after Circuit Court Judge Learned Hand found the Aluminum Company of America (commonly known as ALCOA) liable for monopolization in a landmark case, the market definition process started to become more refined, primarily focusing on how products were similar and interchangeable such that they performed comparable functions. At the same time market definition took on more complexity, antitrust enforcement exploded and courts became flooded with antitrust litigation. Given the circumstances, the Supreme Court felt that it needed to provide litigants with more structure to the antitrust laws, not only to effectuate Congress’s intent of protecting freedom of economic opportunity and preventing dominant corporations from using unfair business practices to succeed, but also to assist judges in determining whether a violation occurred. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Supreme Court repeatedly expressed its frustration that there was no formal process for litigants to help the courts define markets.

It took until 1962 for the Supreme Court to comprehensively determine how markets should be defined and bring some much-needed structure to antitrust enforcement. The process, known as the Brown Shoe methodology after the 1962 case, requires litigants to present information to a reviewing court that describes the “nature of the commercial entities involved and by the nature of the competition [firms] face…[based on] trade realit[ies].” With this information, judges are required to engage in a heavy review of the information they are presented with and make a reasonable decision that accurately reflects the actual market competition between the products and services at issue in the litigation.

Constructing a relevant market for the purposes of antitrust litigation using the Brown Shoe methodology can be made using a variety of commonly understood and accessible information sources. For example, previous markets in antitrust litigation have been constructed from reviewing consumer preferences, consumer surveys, comparing the functional capabilities of products, the uniqueness of the buyers or production facilities, or trade association data. In a series of cases between 1962 to the present, the Supreme Court has rigorously refined its Brown Shoe process to ensure both litigants and judges had sufficient guidance to define markets. Critically, in no way did the Supreme Court intend for its Brown Shoe methodology to restrict or hinder the enforcement of the antitrust laws, and the fact that the process relies on readily accessible and commonly understood information is indicative of that goal.

But 1982 was a watershed year. Enforcement officials in the Reagan administration tossed aside more than a decade of carefully crafted jurisprudence from the Supreme Court in favor of complex, unnecessary, and arbitrary tests to define a relevant market. The new test, known as the hypothetical monopolist test (HMT), which is often informed by econometric models, asks whether a hypothetical monopolist of the products under consideration could profitably raise prices over competitive levels. It is tantamount to asking how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. They primarily accomplished this economics-laden burden through the implementation of a new set of guidelines that detailed how the Department of Justice would analyze mergers, determine whether to bring an enforcement action, and how the agency would conduct certain parts of antitrust litigation, one of those aspects being the market definition process.

From the 1982 implementation of new merger guidelines to the present, judges and litigants, predominantly federal enforcers, have ignored the Brown Shoe methodology and instead have embraced the HMT and its navel-gazing estimation of angels. As a result, courts now entertain battles of econometric experts, over what should amount to a straightforward inquiry.

As scholar Louis Schwartz aptly described, the relegation of the Brown Shoe methodology and its brazen replacement with econometrics under the 1982 guidelines represented a “legal smuggling” of byzantine economic criteria into antitrust litigation.

Besides facilitating the de-economization of antitrust enforcement, abandoning the econometric process would have other notable benefits. First, relying entirely on the Brown Shoe methodology would restrict the power of judges, lawyers, and economists by making the law more comprehensible to litigants. Giving power back to litigants would contribute to making antitrust law less technocratic and abstruse and more democratically accountable. For example, in some cases, economists have great difficulty explaining their findings to judges in intelligible terms. In extreme cases, judges are required to hire their own economic experts just to decipher the material presented by the litigants. Simply stated, the law is not just for economists, judges, or lawyers; it is also for ordinary people. Discarding the econometric tests for market definition facilitates not only the understanding of antitrust law, but also how to stay within its boundaries.

Second, reverting to the Brown Shoe methodology would make antitrust law fairer and promote its enforcement. The only parties that stand to gain from employing econometric tests are the economists conducting the analysis, the lawyers defending large corporations, and corporations who wish to be shielded from the antitrust laws. Frequently charging more than a $1,000 dollars an hour, economists are also extraordinarily expensive for litigants to employ, creating an exceptionally high barrier to otherwise meritorious legal claims.

Since 1982, market definition in antitrust litigation has lingered in a highly nebulous environment, where both the econometric tests informing the HMT and the Brown Shoe methodology co-exist but with only the Brown Shoe methodology having explicit approval by the Supreme Court. Even in its highly contentious and confusing 2018 ruling in Ohio v. American Express, the Supreme Court did not mention or cite the econometric processes currently employed by courts and detailed in the merger guidelines to define relevant markets. In fact, in a brief statement, the Court reaffirmed the controlling process it developed in Brown Shoe, yet lower courts continue to cite the failure of plaintiffs to meet the requirements of the econometric market definition process as one of the primary reasons to dismiss antitrust cases. Putting it aptly, Professor Jonathan Baker has stated that the “outcome of more [antitrust] cases has surely turned on market definition than on any other substantive issue.”

While the econometric process is not the exclusive process enforcers use to define markets in antitrust litigation and is often used in conjunction with the Brown Shoe methodology, completely abandoning it is critical to de-economizing antitrust law more generally. Since the late 1970s, primarily due to the work published by Robert Bork and other Chicago School adherents, economics and economic thinking more generally have become deeply entrenched in antitrust litigation. Chicago School thought has essentially made antitrust enforcement of nearly all vertical restraints like territorial limitations per se legal, and since the 1970s, the Supreme Court has overturned many of its per se rules. Contravening controlling case law on vertical mergers, Chicago School thinking has resulted in judges viewing them as almost always benign or even beneficial and failing to condemn them by applying the antitrust laws. Dubious economic assumptions have significantly restricted antitrust liability for predatory pricing, a practice described by the Supreme Court in 1986 as “rarely tried, and even more rarely successful.” As a result, economic thinking and econometric methodologies, though running contrary to Congress’s intent, have served to undermine the enforcement of the antitrust laws. This is not to say there is no role for economists. Economists can engage in essential fact gathering activities or provide scholarly perspective on empirical data that shows how specific business conduct can adversely affect prices, output, consumer choice, or innovation. For example, economic research has found that mergers and acquisitions habitually lead to higher prices and increased corporate profit margins – repudiating the idea that mergers are beneficial for consumers. But economists have little value to add when it comes to market definition.

Reinstituting many of the overturned per se antitrust rules all but require a change of precedent from the Supreme Court, which appears highly unlikely given the ideology of most of the current justices. However, modifying the process that enforcers use to determine relevant markets does not require overcoming such a seemingly insurmountable hurdle. Ridding antitrust litigation of the econometric process would simply require enforcers, particularly those at the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, to completely abandon the process altogether in their enforcement efforts (particularly in the merger guidelines) and instead exclusively rely on the Brown Shoe methodology. Neither the law nor the jurisprudence would need to be modified to effectuate this change—although it might be helpful, before unilaterally disarming, to first explain the new policy in the agencies’ forthcoming revision to the merger guidelines.

While some judges currently ignore or dismiss the Brown Shoe methodology, were enforcers to completely abandon the econometric process for defining markets, courts effectively would have no choice but to rely on the controlling Brown Shoe process. Unlike other aspects of antitrust law, enforcement officials can and should fully embrace the controlling law, in this case Brown Shoe, and use it readily, leaving private litigants to employ the econometric process if they so chose. Nevertheless, history indicates that courts are highly deferential to the methods used by federal enforcers—especially when explicated in the merger guidelines—and private litigants would likely follow the lead of federal enforcers in deciding which method to use to define relevant markets.

Currently, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission are redoing and updating their merger guidelines. To continue facilitating the progressive antitrust policy that began with President Biden’s administration and to start broadly de-economizing antitrust litigation, both agencies should seize the opportunity to jettison the econometric-heavy market definition tests and enshrine this change within the updated merger guidelines. Enforcers should instead exclusively rely on the sensible, practical, and fair approach the Supreme Court developed in Brown Shoe.

—

Daniel A. Hanley is a Senior Legal Analyst at the Open Markets Institute. You can follow him on Mastodon @danielhanley@mastodon.social or on Twitter @danielahanley.