Wielding a sink, Elon Musk entered Twitter HQ on October 26, 2022 and proceeded to do precisely that to the platform’s reputation. Since his ascension to the Twitter throne, Musk’s actions have drawn widespread ethical and moral repudiation, motivated in part by his courting of accounts known for promoting hatred and anti-Semitism. Undaunted, Musk has pressed forward on the same path, ownership of the company bestowing upon him the latitude to act as its sovereign, unencumbered by ethical considerations and guardrails implemented in Twitter’s previous corporate structure as a public entity.

Actions have consequences, as the Merovingian once so eloquently explained in The Matrix, and Musk’s steps prompted a predictable exodus of advertisers eager to avoid any association between their brands and the sort of voices that Twitter has recently released from its digital Tartarus. Concurrently, users also began to seek out possible alternatives to the platform, as racist tweets proliferated under the new management’s permissive (if not outright sympathetic) attitude toward the far right (conducted under a “free-speech” pretext, of course). While potential Twitter alternatives had previously risen to meet consumer interest, the recent demand for Twitter substitutes represents a clear ideological reversal of the pre-Musk era. Then, the far-right wing of the Republican party, feeling slighted by the banishment of extremist voices in its ranks from Twitter, sought a suitable safe space in Parler, Gettr, and Truth Social. Notably, none of these have mustered anywhere near the audience to rival Twitter despite substantial funding and the presence of the former White House occupant on Truth Social.

Of late, potential competition to Twitter has arisen in the form of Mastodon, a six year-old open-source software platform for operating decentralized social networking services (i.e., you sign up on Mastodon on a specific server, some of which are invitation-only). Other nascent players include Nostr (an open-source protocol) and Post (a self-described source for premium news content without ads or subscriptions founded by former Waze CEO Noam Bardin). Whether these sites emerge as anything more than fringe competitors remains to be seen, though Twitter’s recent actions reveal some concern as to their likelihood of success. Which brings us to the topic of this article.

In the past several days, Twitter adopted new policies, engaging in conduct that has drawn attention in antitrust circles. Specifically, Twitter 1) suspended the official Mastodon account (@joinmastodon) then 2) implemented a new Promotion of alternative social platforms policy on December 18, 2022. The policy prohibited users from promoting themselves on other platforms while on Twitter (examples of prohibited phrases include “follow me @username on Instagram” and use of ”username@mastodon.social”). Notably, the policy allowed alternative platforms to advertise on Twitter, but prohibits users from promoting their own presence on those sites. As I explain below, this distinction informs the nature of Twitter’s anticompetitive conduct.

The fact that Twitter rolled out this policy without apparent regard for its alignment with antitrust laws outside the United States offers some insight into Musk’s haphazard and whimsical leadership. As many across social media pointed out, the new policy appears to violate the European Commission’s Digital Markets Act, which, inter alia, states that gatekeeper platforms may not “prevent consumers from linking up to businesses outside their platforms.” The DMA levies significant penalties for non-compliance: up to 100% of total worldwide annual turnover (sales) and up to 20% in the event of repeated infringements. The question of whether Twitter qualifies as a gatekeeper platform remains, though the likelihood of the answer being yes appears rather evident: Twitter deleted the policy from its web site by approximately 10:15pm on the same day it published it (December 18, 2022).

The question of whether the policy still exists in substance if not in form aside, let’s see how it would fare in the generally more permissive US antitrust arena.

Judging by some of the articles recently posted, the immediate focus appears to lie with whether Twitter has the freedom of refusal to deal. In other words, does Twitter have any statutorily-enforceable duty to deal with its actual or potential competitors? While regulatory agencies generally permit a business to choose its partners as it deems fit, the existence of market power and its likely exercise thereof place some boundaries on such freedom. For example, in US v. Dentsply, the 3rd Circuit explained that “Behavior that otherwise might comply with antitrust law may be impermissibly exclusionary when practiced by a monopolist.” Further, Twitter’s refusal to deal in this case rests less vis-à-vis its competitors and more with regard to its own customers. In other words, the extent to which Twitter has “refused” to deal with Mastodon, for example, is only by suspending its Twitter account. (Notably, it has NOT done the same for Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, or even Parler.) In contrast, Twitter has flexed its power over its own users, threatening them with requiring deletion of tweets and temporary account suspension for isolated incidents or first offenses to permanent suspensions for subsequent offenses.

Condemnation of such actions under antitrust law (i.e., the Sherman Antitrust Act) has legal precedent. For example, Lorain Journal Co. v. United States involved the case of a dominant newspaper (the Lorain Journal), which sought to foreclose competition from the Elyria-Lorain Broadcasting Company, which operated a radio station called WEOL located eight miles south of Lorain. A “substantial number of journal advertisers” also sought to advertise on WEOL, to the chagrin of the Lorain Journal, which conceived a plan to decline “local advertisements in the Journal from any Lorain County advertiser who advertised or who appellants believed to be about to advertise over WEOL.” The Journal monitored the radio station’s advertisers, and terminated the contracts of those that advertised there, agreeing to reinstate their ability to advertise in the Journal only after they had ceased advertising on WEOL.

The court found that the Journal’s intent was to “destroy the broadcasting company” and that “Having the plan and desire to injure the radio station, no more effective and more direct device to impede the operations and to restrain the commerce of WEOL could be found by the Journal than to cut off its bloodstream of existence — the advertising revenues which control its life or demise.”

Note the Court’s use of the term “direct”. We’ll come back to that in a moment.

Importantly, the Supreme Court did not find that the Journal’s scheme had to be successful to establish a case of attempted monopolization. Rather, the injunctive relief “sought to forestall that success” and save WEOL.

Why would such precedent apply here? After all, Twitter does not prevent users from having accounts on Mastodon, for example, they just cannot advertise doing so on Twitter. The goal, however, remains the same: to deprive Mastodon or a similar competitor of the required competitive oxygen required for critical mass. In the case of digital platforms, that oxygen comes in the form of network effects. The necessity of benefiting from such effects forms a substantial barrier to entry for nascent platforms.

Network effects occur when one customer of a particular product benefits from its use by other customers. For example, part of the attraction of a dance club lies in its popularity with other individuals. The term social “network” implies exactly such effects – users benefit from interaction with each other. Curtailing a club or a social network’s ability to increase its customer base threatens its very existence. Such network effects carry critical importance among digital platforms – they sustain industry behemoths like Facebook, Google, Amazon, YouTube and others, and they serve the same function with Twitter.

But wait, you ask, this explanation still doesn’t address the key point: can’t people just establish the same network effects at Mastodon? To address this question, let’s introduce two more related economic concepts: (1) transaction costs and (2) lock-in.

Transaction costs are just that: costs that a participant in an exchange must incur to consummate that transaction. In this case, such costs take two primary forms – the costs of moving one’s own account, and the cost of others not moving theirs, the latter reflecting a coordination problem. Take the case of a popular Twitter user with many followers. That users has expended substantial effort in establishing a follower base and will be loath to migrate to a different platform if that base does not follow or if she risks losing a substantial portion of it and must rebuild the rest. In turn, the user with few followers maybe less concerned with losing their own base and more concerned with moving to a platform that does not have key accounts of interest, requiring the user to multi-home (expend effort across multiple platforms rather than just one).

Such risks of starting anew elsewhere represent transaction costs associated with that migration. These costs also create lock-in, an economic inertia that occurs when a customer becomes dependent on the services of a single vendor, allowing that vendor to exert some degree of market power over the consumer (more on this in a second). For example, lock-in features prominently among legacy mainframe users, who cannot readily migrate certain workloads off the mainframe to the cloud, in large part because their mission critical applications rely on legacy code written in COBOL over the last fifty-plus years. Readers may remember New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy’s April 2020 call for volunteer COBOL programmers who could help the distribution of unemployment aid during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The same concept applies here. Many Twitter users have established deep roots on Twitter, which has become a de facto archive of evidence. One can search for posts, articles, and the like for years prior, from institutions and users across the world. When autocracies crack down on dissidents or mass protests rise up to voice the will of the people, images often first appear on Twitter, where they are recorded for posterity and remain as a chronicle of humanity’s early experimentation with technology. While Twitter users can save and download their own archives, their whole as it appears on Twitter is surely greater than the sum of their individually-distributed parts.

Critically, the presence of lock-in indicates that the company that wields it has market power, commonly a critical ingredient when evaluating actual or potential anticompetitive conduct. What do we mean by that? In a recent CNN piece, Brian Fung defined the term as “dominance in a specific market that regulators would be expected to describe and explain in any lawsuit.” While this definition may reflect its understanding in the vernacular, Mr. Fung’s definition doesn’t accurately capture the concept.

In economic terms, market power just means the ability to set price above marginal cost. In other words, market power arises when a firm can set its own price above levels that would predominate under competitive conditions. Monopoly power, in cases of unilateral conduct (such as the present), “is the power to control prices or exclude competition.” But doing so may just reflect a firm’s superior business acumen, exploitation of which does not invite antitrust scrutiny, as the Supreme Court established in US v. Grinnell Corp. (1966). However, “Where monopoly power is acquired or maintained through anticompetitive conduct, however, antitrust law properly objects.” The relevant question at hand is whether Twitter’s recent conduct falls into this category. More importantly, however, the question we truly want to answer is whether Twitter’s actions harm competition or, as the Supreme Court explained in FTC v. Indiana Fed’n of Dentists, its actions generate “potential for genuine adverse effects on competition.”

As the late legal scholar Phillip Areeda noted (and the Court cited in Indiana Fed’n), market power is but “a surrogate for detrimental effects.” Economists and competition scholars have two primary methods of informing the existence of such detrimental effects (i.e., harm to competition) at their disposal: (1) direct evidence, and (2) indirect inference. Direct evidence is exactly that: observational evidence that a company (or a group in the case of collusive conduct) has attempted to exclude competition or raise its price above competitive levels (or lower output).

Absent such direct evidence, we may infer anticompetitive effects indirectly by defining a “relevant market” and calculating market shares. But market definition is not a requirement nor does it exist in a vacuum – its sole purpose is to illuminate market power and permit the inference of anticompetitive conduct. (It is however true that Courts have commonly required that Plaintiffs delineate at least “the rough contours” of a relevant market.)

For example, in the NCAA antitrust cases, the fact that defendant schools colluded to fix athlete wages below competitive levels was clear and obvious. Defendants admitted as such and the bylaws enshrined their conduct. These facts represented direct evidence of anticompetitive conduct. Attempting to define a relevant market adds little, if anything at this point and represents largely a Rube Goldberg machine, a complex exercise designed to prove the already obvious.

Nonetheless, let’s apply both methods here. First, do we have any evidence of monopoly power and its exercise to the detriment of competition? Absolutely. Twitter’s recent actions have illuminated the existence of lock-in through power it affords the platform over its users. You might respond, “Wait a second, Twitter offers a freemium model – using the platform is free, unless one wants blue checkmark available through the $8/month Twitter Blue subscription.”

Not quite. Digital platforms like Twitter, Facebook, or YouTube are not “free”. Just as in a barter economy, they require in-kind payment. The platforms give users access, while the users provide critical data that the platforms then sell to advertisers. As Judge Koh explained in her January 13, 2022 order in Klein et al. v. Facebook,

“In other words, users provide significant value to Facebook by giving Facebook their information—which allows Facebook to create targeted advertisements—and by spending time on Facebook—which allows Facebook to show users those targeted advertisements. If users gave Facebook less information or spent less time on Facebook, Facebook would make less money.”

The same applies to Twitter. In-kind transfers represent the operative currency on digital platforms that use such models. The platform can “raise the price” to the user by 1) diluting the quality of the user’s experience on the site or 2) taking steps to prevent the user from multi-homing or de-platforming entirely. The European Commission’s prohibition of such actions through the DMA reflects precisely these concerns.

Twitter has done exactly that, as evidence by the increase in racial animus, decline of content moderation and gutting of staff responsible for maintaining site quality. More directly, Twitter has threatened its users with banishment if they reveal their use of another platform or solicit actual or prospective followers to follow them on another platform. Doing so increases the user’s costs, particularly to the extent that a user leverages such platforms for brand-building and cannot cross-pollinate across them. A user may do so, to avoid lock-in – Twitter’s actions reflect an acknowledgement of this motivation and a desire to maintain the power that lock-in grants it over its users. Its recent ban on multiple journalists under the specious pretext of “security” represented a disciplinary tool for its broader user base, not so subtly implying that “if we can ban them, we can certainly ban you.” If users could decouple from Twitter without losing their efforts and temporal investments, such threats would be self-defeating on the part of the platform. Such threats reflect no exercise of superior business acumen but rather a desire to maintain a dominant position by undercutting possible alternatives and avoiding the crucible of competition.

Now let’s turn to the second means of establishing harm to competition: indirect inference through a relevant market definition. First, let’s clarify one point that motivates this exercise: We want to determine which competitors, if any, could discipline Twitter’s ability to raise prices to its users or otherwise harm competition.

In case of regulatory intervention, market definition would likely involve substantial amount of data analysis. Fortunately, given the digital nature of such markets, data are plentiful. Aside from Defendant data, third parties such as Comscore, Nielsen, and Semrush either collect their own data, contract with third parties to obtain it, or both (as in the case of Comscore, for example.) Of course, for the purposes of this article, I did not have access to the more expensive sources, so I relied on Semrush’s collected data.

Twitter operates as a microblogging service where users can post short messages accompanied by links or images. The service maintains a searchable repository of such messages (“tweets”), forming a historical records. Other sites provide similar services, though among the microblogging sites, Twitter dominates in terms of user share, as the table below shows, with a 99% share of total visits and 95% share of unique visitors.

Visitor Data for Major Microblogging Services, November 2022

Source: Semrush Traffic Analytics

| Site | Visits | Unique Visitors | Market Share (Visits) | Market Share (Visitors) |

| twitter.com | 8,300.00M | 2,200.00M | 99.32% | 95.45% |

| truthsocial.com | 30.30M | 91.00M | 0.36% | 3.95% |

| gettr.com | 12.30M | 4.80M | 0.15% | 0.21% |

| joinmastodon.org | 7.80M | 5.70M | 0.09% | 0.25% |

| post.news | 3.10M | 2.20M | 0.04% | 0.10% |

| parler.com | 1.90M | 0.66M | 0.02% | 0.03% |

| tribel.com | 1.30M | 0.53M | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| nostr.com | 0.0025M | 0.0015M | 0.00003% | 0.00007% |

Of course, a likely rejoinder would posit that a market definition should include social media giants Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram, along with perhaps TikTok and Reddit. However, if these platforms could discipline Twitter, we would not have observed the proliferation of right-wing microblogging sites Truth Social, Parler, Gettr, and Rumble (nor their spectacular failures). For the interested reader, I’ve included a larger table that may be of interest at the conclusion of this article.

Twitter’s dominant market share reflects the direct evidence of anticompetitive harm: the platform has sufficient market power to deprive nascent competitors that could threaten its hegemony and increase users’ costs of using the site (even if such costs are not measured in fiat currency).

Whether such evidence prompts regulatory agencies to take steps to curtail Twitter’s antics remains to be seen. The harms appear to align with the type of conduct prohibited by Section 2 of the Sherman Act (unilateral attempt to monopolize) and Section 5 of the FTC Act (unfair or deceptive acts or practices). Nonetheless, as this article demonstrates, the evidence indicates that Twitter has the ability to harm competition and has already launched an attempt to do so by restricting users’ abilities to migrate to other nascent platforms. As Musk himself tweeted:

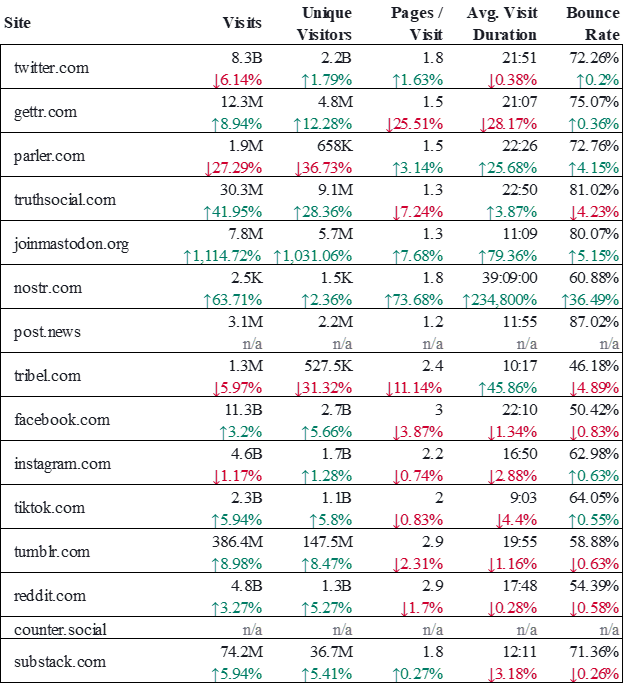

Finally, for readers interested in the various performances of microblogging and social media sites in this market periphery, I report the November 2022 data from Semrush for these platforms. The green and yellow figures below the November data reflect the performance relative to October 2022 (e.g., Twitter visits fell by 6.14% but unique visitors rose by 1.79%).

November 2022 Traffic for Social Media/Microblogging Platforms

(Source: Semrush Traffic Analytics)