Price inflation has been the dominant economic concern for Americans in the post-Covid era. The rising prices of cars, groceries, and healthcare (especially given recent Congressional inaction) have all imposed increasing burdens on the average American. Despite the consistent price hikes for those items, all of them pale in comparison to the skyrocketing rental costs that Americans have endured since the pandemic. Per Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, a record 12.1 million renter households were spending at least half of their incomes on housing in 2022, putting them at increased risk of eviction and homelessness.

According to Zillow, rental prices have increased by more than a third since the pandemic, while the median household income has risen by only 22 percent. As the gap between earnings and rent prices widens, families are forced to stretch their budgets to afford shelter. In cities, these higher rental prices have forced families out of their neighborhoods in search of more affordable housing. The press and politicians have both acknowledged the affordability problem that has resulted from the recent housing crisis wave. Indeed, in September 2025, the U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent noted that the Trump administration was considering declaring a “national housing emergency” to address affordability.

So it was odd that The Economist last week sought to deny the reality that is in front of our faces. In a briefing titled “America’s affordability crisis is (mostly) a mirage,” the magazine asserts that “on the economics, Messrs Trump, Bessent and Duffy have a point” when they claim that the affordability crisis amounts to a “hoax” and a “con job.”

The Economist brings this same skepticism to the rental affordability crisis. A widely used industry rule-of-thumb is that rents are affordable so long as they account for less than 30 percent of a renter’s income. While acknowledging that “the squeeze for [home] buyers is real,” The Economist dismisses the concerns about rental affordability:

Until rates began rising in 2022, the average home in most counties was affordable by the 30% rule-of-thumb, even for buyers with only a 10% downpayment. Now, most are not (see chart 4). Homeowners who fixed their mortgages before rates went up have dodged this. The average rate on all outstanding mortgages is still only 4.3%, nearly two percentage points less than the average rate on new mortgages. Still, the squeeze for buyers is real. Rents, which are less directly affected by mortgage rates, are more affordable: the average in most counties is still below that 30% threshold. (emphasis added)

Whether The Economist intentionally aims to gaslight its readers or simply has not given the issue the requisite thought it deserves is unclear (we’ll generously assume the latter), but either way, this curious statistic does not support the claim that rents are generally affordable.

Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics

Let’s start by ascertaining where The Economist likely came up with this figure. The exact methodology is uncertain, but Figure 4 in its briefing relies upon Zillow, The Census Bureau, FRED, and the Insurance Information Institute. Because Zillow’s Observed Rent Index only has information for a subset of counties in the United States, the magazine’s county-level analysis likely came from the Census American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS collects annual county-level data on rent prices, income, population, and other demographic variables. That gives us the exact information we need to kick the tires. Given this uncertainty, we use the 2023 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

By comparing the median rental price to the median household income in each county in the 2023 ACS, we can replicate The Economist’s conclusion—namely, that “most” of the counties enjoy rents of less than 30 percent of income. There are at least two fatal flaws, however, with that analysis.

First, the number of counties is not the relevant unit of analysis. We want to analyze the cost of living for people. This mistake is akin to the misleading map of the United States showing which candidate won county, which ignores the fact that people vote, not land. Second, looking at the median household income understates the problem because it combines homeowners and renters into the same category. The median homeowner household has nearly double the income of the median renter household. Using the median renter’s income is a better estimate of how the usual renter is doing.

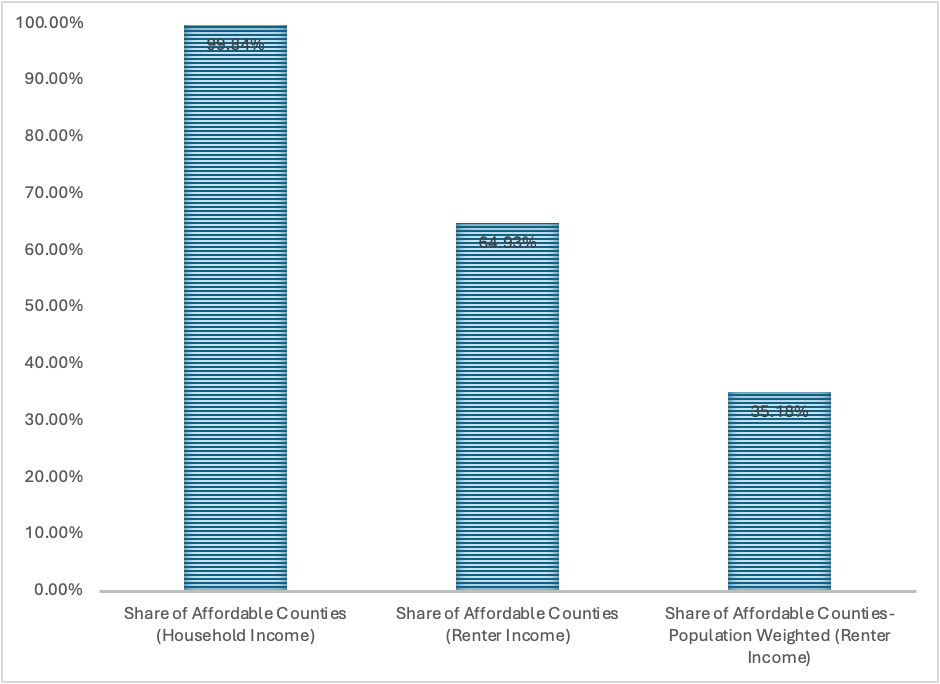

Adjusting the rental analysis to measure affordability using renter’s income and taking into account population gives a much different result: the median rent is affordable—that is, it is below 30 percent of income—for slightly more than a third of the population. The rental affordability issue shouldn’t be seen as a coastal problem affecting a handful of cities; it’s endemic across the United States. The figure below shows that just these two adjustments to The Economist’s statistic make a significant difference when measuring rental affordability. The first adjustment (measuring renter income rather than household income) brings the proportion of affordable counties down from 99.8 percent to 64.9 percent. A second adjustment, measuring the population in affordable counties (rather than naively treating all counties equally) shows that only 35.2 percent of the population lives in counties meeting the rental affordability threshold.

Source: 2023 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

We cannot be sure whether The Economist’s “average-in-most-counties” statistic was based on the first or second bar; in any event, both overstate rental affordability. The extent of the affordability crisis can be verified using more recent 2024 ACS data. Among the 46.1 million renters recorded in 2024, 22.3 million renters (48.4 percent) paid 30 percent or more of their income on rent. Of these, 11.2 million renters paid half or more of their income on rent. Despite the assurances of the neoliberal magazine, the rental affordability crisis is real for millions of people.

Being Honest About The Crisis

As the saying goes, the first step to recovery is admitting you have a problem. We have a serious rental affordability problem in this country that demands real solutions. There has been much progress in recent years with rent control, zoning reforms, tenant protections, permitting reform, and antitrust action (such as against RealPage). Yet these are small victories that need to be built upon and extended. Ignoring the rental problem will only cause the overburdened renter to fall further behind.

Given the flimsiness of The Economist’s rental affordability figure and the stridency of its advocacy—the briefing reviewed here serves as supplement to last week’s cover story—one wonders why the editors of such an esteemed publication want to deny there’s an affordability problem. Presumably the corporatist class whose concerns The Economist seeks to assuage fears any interventions in the market to the solve the problem. One such intervention that’s rightfully gaining traction among economists is rent controls. Neale Mahoney and Bharat Ramamurti recently endorsed price controls, including for rents, in the opinion section of the New York Times, explaining that “Rent caps focused on existing units, combined with government investment in new housing and reforms to zoning, permitting and other land-use regulations, can protect tenants from rent spikes, while encouraging new construction to build the three to four million homes that economists believe we need to make up the shortfall in the housing supply.” Similar to climate-change deniers, if neoliberal economists deny the affordability problem, they don’t have to address it.