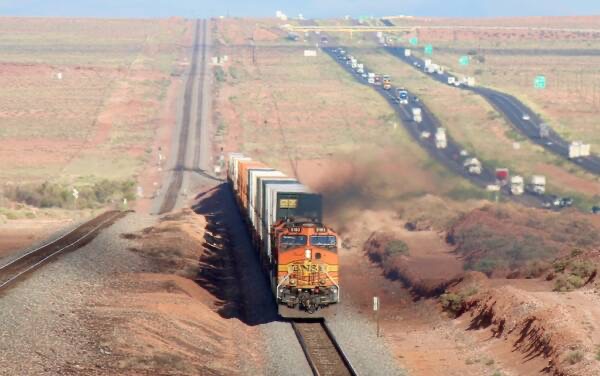

The proposed merger of the Union Pacific (UP) and Norfolk Southern (NS) railroads would consolidate ownership and control of a significant part of the central arteries or “trunk lines” of the rail network in this country. Currently, four railroads control most of these key components of the rail network, especially for the east-west service, and each has a clear regional dominance. The other two major trunk line railroads are the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) and CSX. A number of “branch lines” extend out from the trunk lines, and they are often operated by short line railroads. Although there are 600 short lines, a number of them have common ownership.

Proponents of the UP-NS merger argue that it would allow the combined railroad to operate trains from the west coast to the east coast without having to switch the cars between rail lines at some transfer point. It is speculated that if the UP-NS merger is allowed, the BNSF and the CSX would then seek to combine, creating even more concentrated control over trunk lines. The current position of the BNSF and CSX is that, even without a merger, they will jointly offer through service from west coast ports to various locations in the eastern half of the country. This service would use the same train for the entire trip with crews changing as the train moves from one system to the other. Notably, the routes that they propose for this combined service will directly overlap and compete with the UP-NS lines. All the major trunk lines already share track usage in some places with each other or with short lines. Furthermore, Amtrak, which only owns a few lines in the Northeast, has operated trains on the trunk lines of all major railroads for its nationwide services since its creation in 1971. In addition, many of the freight railcars in use belong to third parties that use them for their own goods or lease them to others for use. All of this shows that ownership of trunk lines is not essential to the operation of freight or passenger service on those lines.

Increased consolidation of ownership of trunk lines might induce their rationalization and enhancement to facilitate more efficient movement of trains. But this would come at the cost of increased dominance of these essential transportation facilities. Moreover, much of the rationalization and improvement is rational conduct by each major trunk line without any merger. Hence, the proposed UP-NS merger should be forbidden as long as the resulting company both owns the tracks and controls their use.

Beware the Bottlenecks

Trunk lines can be understood as “bottlenecks” through which the bulk of rail freight must pass. Ownership of trunk lines confers the ability to control the use of the capacity—namely, whose trains at what price will operate on those lines. Because the owner also controls the dispatch of trains on the line, it has substantial capacity to affect the quality of service. For example, Amtrak, which enjoys a right to use trunk lines for its services, has a long history of problems of having its trains delayed so that the trunk line owner can send the latter’s freight trains ahead. Where freight lines share track use rights, similar disputes are not uncommon between the track owner and the other railroad sharing that track.

What is concentrated is the control over the track itself. Major interstate highways are a single system with multiple users. The same is true of the inland waterways. Should ownership of railroad trunk lines be separated from operation of freight service by multiple users? Amtrak’s and freight lines’ shared use of some trunk lines suggest that operating freight and passenger trains do not require owning the trunk lines on which those services operate. Moreover, while the capacity of any rail line is ultimately limited, with proper scheduling and dispatch these lines can accommodate substantial increased use. It follows that if ownership of the trunk lines were separated from the operation of freight service, it is probable that the number of competitors in providing such service would increase. Freight rates would likely decline, and assuming proper coordination of use, service itself would increase in efficiency. In particular, services such as the movement of container shipments would likely increase significantly, as trucking companies as well as new entrants would be able to develop a range of through services. The same might be true for passenger service, but given low total demand, this seems unlikely except in a few potentially high-volume routes

The collaboration of BNSF and CSX to provide a through freight service from coast to coast absent any merger demonstrates the feasibility of such service. Not surprisingly, that proposed service will focus on competing directly with the potential (merged) UP-NS services. This highlights the importance of competition in stimulating innovation in transportation service. Notably, the other ports on the west coast that BNSF serves, but which do not have UP-NS alternatives, are not in the through services package.

As noted, there are significant problems with the coordination in the use of trunk lines. There are ways to coordinate use to facilitate more efficient shared use of track. The railroad controlling the line, however, has limited incentive to resolve those problems because it has a conflict of interest. Its rational goal is to maximize its own use rather than facilitate the use by others whether they provide a distinct service like Amtrak or are competitors in freight service as in the case of shared track rights.

Experience with Separating Ownership from Operation

Some countries have experimented with separating ownership of the tracks and licenses for operators to use those tracks to stimulate competition in rail services. A leading example is the United Kingdom. In the 1990s, the publicly owned national rail system was terminated. Regional passenger services devolved into private ownership but retained a localized monopoly. In addition to the regional services, long-distance passenger services emerged that provided some competition. Freight service was similarly privatized but in a manner that encouraged competition. A distinct but private authority maintained the tracks and provided coordination of services.

By 2024, parts of that experiment failed. The government had retaken the responsibility for ownership and coordination of the rail system itself because of concerns about maintenance of the rail lines. It has similarly retaken ownership and operation of some regional passenger services that had persistent problems in both finances and operations. In 2024, the new Labor government determined that as the remaining contracts for the regional service expire, their passenger service will be absorbed into a state-owned entity that will provide service in the England and the parts of Wales and Scotland where those regions had not already recaptured public ownership of local passenger service.

On the other hand, the independent freight services and long-distance passenger services will continue to operate. The distinction is that the regional services were local monopolies of rail passenger service, while both the freight services and the long-distance passenger lines operated in a competitive environment. There are five major freight services competing in the UK market. The American short line holding company, Genesee & Wyoming, owns one of the leaders, Freightliner, which is particularly strong in handling containers, including offering its own trucking service to deliver the container.

Remedy Design for the STB

If the UP-NS merger is to be allowed, there should be separation between ownership of the tracks and operation of the freight services on those tracks. Because the law exempts these mergers from standard antitrust review, the decision will come exclusively from the Surface Transportation Board (STB), whose authority to regulate the operation of the rail system extends beyond standard antitrust criteria to encompass a broader concern for the overall public interest in the rail system. If it adopts this strategy, the STB should also require the BNSF and CSX to make a similar separation of rail lines from their operation of freight services. Indeed, this separation should also apply to the other two Class I railroads—the Canadian Pacific Kansas City and Canadian National. Doing so would immediately create six freight service operators even if the STB did not require subdivision of the operating companies. Of course, new entry would have to be authorized as well. The Genesee and Wyoming Railroad is among the most obvious entrants given its UK experience and expertise. The STB would have to develop standards for entry and define the rights of such firms. It might be necessary to have criteria for use of trunk lines such as those into the Los Angeles area, which might have capacity limits.

A central question would be the form of ownership and management of the trunk system. Private ownership would risk exploitation, as such an owner would have monopoly power over the use of its track. The STB would have to impose rate regulation to avoid overcharges. Perversely, the track owners will then have the incentive to make overly costly investments if rate regulation is based on the assets devoted to the business. This is the history of regulated public utilities where rates are based on the capitalized value of the investment in the facilities. If rates are not based on capital investment, however, there would be an incentive to underinvest in the maintenance and improvement of the rail lines. A related risk is the control over dispatch along lines. An owner might have incentives to favor some users over others or use this control to demand additional compensation for priority.

It is very hard to imagine that the American government would take ownership of the rail system even though it “owns” and maintains both the highway and inland waterway systems. Not only the UK, but many other countries have public ownership of their rail systems. Early in the development of America’s railroad system, states were often the owners of the lines that operating companies used and North Carolina still owns a major trunk line in that state. Indeed, Amtrak is a government entity reflecting the failure of private companies to maintain a successful national rail passenger system. But Amtrak’s problems with getting sufficient support to develop and operate its system cautions against government ownership. Indeed, the deferred maintenance for both the national highway system, especially bridges, and the failure to make timely investments in the inland waterways counsel against public ownership. All are dependent on Congressional appropriations.

The source of these problems, whether privately or publicly owned, is the conflict of economic interest between rail users and the track owner. Darren Bush and I have suggested that one solution to dealing with the operation of bottlenecks is to have the ownership rest in either a cooperative owned by the users or by creating a condominium type of ownership in which owners of specific use rights share ownership but not management of the overall entity. Both strategies assume that there are a significant number of users whose primary interest is in using the bottleneck as a means to provide some valuable good or service. Hence, the goal of these owners is to maximize the utility of the bottleneck for all its users. This means providing as much access as is technologically feasible, ensuring proper investment in maintenance, and providing the kinds of coordination that would again maximize the use of the resources involved. Our article showed that such strategies have in fact been used successfully in a variety of contexts—from cooperative grain elevators at a time when farmers faced very local, monopsonistic markets for their grain to electric transmission that facilitated the opening of competitive markets for the sale of electricity to local utilities.

In the case of railroads, given the goal is to have actual and potential competition for freight service between all major markets, the logical option for the trunk lines is that of a cooperative in which the users would collectively own and manage that essential element of the business. Given a large number of participants, a necessary element to ensure that the incentives to exploit or exclude are minimized, the day-to-day operations would have to be run by a board of directors and managers. The key here is that the incentives of management would be the efficient and open operation of the trunk system.

Remaining Challenges Are Big But Solvable

There are many other hurdles that would have to be overcome to make this transformation possible. During a substantial transition period, the STB would have to play a strong role in policing conduct and guiding the development of the new system. The lessons of path dependency tell us that there are almost certain to be major challenges from unexpected problems with such a transition, but there can also be unexpected positives. Among the issues that would need resolution are the ownership and relationship of the short lines and branch lines owned by the major truck lines to the system. While having all rail lines owned by one or more cooperatives is a possibility, given the limited and often focused use made of branch lines, creating a distinct ownership model for such lines might be a better strategy. A similar issue would arise with respect to the switching yards in which trains are made up, and cars are moved around either for unloading or to be dispatched to a new location. Who would own and operate those entities and how would they relate to the operating companies? The experience of the UK system should be instructive.

Yet another challenging issue is the development and operation of a dispatch system that would coordinate not only the freight services but also Amtrack and any other passenger service that might immerge. Interchange among carriers would require development of protocols. This is likely to be especially challenging for low volume freight service that smaller users require. With the technology from AI and other computer systems such as those currently coordinating air traffic, these problems are solvable but nonetheless challenging.

Finally, there is the major question of pricing. The cooperative presumably would have purchased the rail trackage from its prior owner. The price has to be set in some equitable way and the resulting access charges appropriately allocated among uses. Here there would be real questions about differentiation of prices for through service for trains carrying containers, passenger service, as well as unit trains carrying bulk commodities such as soybeans, coal, corn, or oil.

As the foregoing review suggests a great leap into a cooperative trunk system seems very risky. Perhaps in addition to blocking the UP-NS merger, the STB could consider requiring access to existing trunk lines for other users given the CSX-BNSF and Amtrak examples. As Neil Averitt has suggested, such mandatory access could be limited to specific routes or kinds of freight such as containers where the Genesee & Wyoming as well as national trucking companies are potential entrants. For the reasons discussed earlier, the conflicts of interest between the railroads and such users would be a problem. Still, experimenting with opening some types of rail service to third party participation would provide a way to test the viability of this concept in the American context, as well as a useful experience about the challenges that would emerge.

Peter Carstensen is Emeritus Professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School.