Last month, Capital One announced that it plans to purchase Discover in a deal worth $35.3 billion. For their campaign to secure regulatory approval, Capital One is trying to act like a benevolent pro-consumer company that will use economies of scale to lower interest rates and ramp up competition with Visa and Mastercard. But that’s probably baloney.

There’s something missing in the conversation around this merger–namely, along what axis competition among card issuers actually happens. Most coverage seems to assume that everything can be grouped into “costs for consumers,” but that’s not the case. To really get at what the deal’s competitive effects would be, we need to understand what kinds of companies Capital One and Discover are, the industries in which they operate, and what competition in those spaces looks like.

Subprime Borrowers Are Likely to Be Injured

There’s a lot of uncertainty about how regulators will handle this deal. For one, there are a lot of different agencies involved in overseeing credit card competition. In order to go anywhere, the merger first requires sign off by both the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Reserve Board (Fed). This is because Capital One is a nationally chartered bank, making the OCC its primary regulator, while Discover is regulated primarily as a bank holding company, which is the Fed’s ambit. To add more acronyms, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), while not primarily involved in the merger approval, could play an advisory role, especially since it is the primary regulator of Discover Bank, which is owned by Discover. Similarly, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) could flag issues with the merger as it serves as a secondary regulator for all large financial institutions. Finally, the Department of Justice (DOJ) could review the merger under the antitrust laws.

While the OCC, Fed, and FDIC have all dragged their feet in updating merger guidelines and have a history of rubber-stamping bank consolidation, the CFPB and DOJ are significant hurdles. The CFPB’s Rohit Chopra and DOJ’s Jonathan Kanter are both ardent anti-monopolists. Under Chopra, the CFPB has been aggressive in reining in the worst abuses from financial services companies. Kanter, for his part, has also implied a willingness to take on bank mergers that other regulators approved. The DOJ also has a bit more latitude to flex its muscles with financial network mergers than when two traditional banks merge.

The most obvious merger harm, on which the DOJ will focus like a laser, is whether the merger will allow the combined firm to raise interest rates on cardholders. Capital One and Discover both cater to subprime (credit score in the 600s) borrowers. And there is less competition for subprime borrowers, which is part of why Capital One was a successful upstart in the credit card industry to begin with. Given that subprime borrowers already have the most limited options in where they can get credit, and given that these cardholders likely shop for credit cards based on which offers the lowest interest rate, it follows that the merger could cause significant harm to an especially at-risk consumer base. The DOJ should define a market (or submarket) for subprime cardholders.

Even for those cardholders with higher credit scores who may not consider interest rates while selecting a card, card issuers do compete on rewards programs, security measures, annual fees, and other features. The merger could eliminate competition between Capital One and Discover on those dimensions as well.

Be Skeptical of Purported Benefits to Merchants

In addition to the horizontal competition mentioned above, Capital One will also gain Discover’s payment processing network, which constitutes vertical integration. As a result, the merged firm will simultaneously hold more market share in credit card issuing, becoming the single largest firm in the space, while also operating a payment network. The deal would, unequivocally, decrease competition in the card issuer space, where just ten firms dominate the industry. But what will happen on the payment processing side is less clear. Capital One argues this aspect of the deal will enhance competition. But for whom?

Card processing is a space dominated by just two firms: Visa and Mastercard. Far, far, far below them, American Express (AMEX) and Discover operate around the edges of that duopoly. As of the end of 2022, Visa and Mastercard’s networks process about 84 percent of all cards in circulation, 76 percent of the total purchase volume, and hold 69 percent of the total outstanding balance across all credit card networks. Capital One’s best case for the merger being procompetitive is that it can become a viable third competitor to those two card processing behemoths. On its face, this seems like a reasonable point, but the mechanics of how it might work are rather fuzzy.

If and when Capital One moves their cards onto the Discover network fully, they will no longer have to pay processing fees to Visa and Mastercard. (It turns out that Capital One represents a much larger share of the total cards of the Mastercard payment processing network). No longer having to pay for those fees is the headline cost saving measure in the deal, but there are potentially others. The merged company may be able to leverage economies of scale to reduce marketing, administrative, or customer service costs as well. So the merged firm may be able to reduce merchant swipe fees or interest rates for cardholders because of those savings. But would they? It’s hard to see a good reason for them to, absent some kind of binding obligation.

Perhaps the merged firm would want to compete more aggressively against Visa and Mastercard for merchants. But cutting merchant fees seems like a pretty naive reading of how credit card purchases work. Discover is already accepted at the overwhelming majority of American retailers. Because most merchants will accept Visa, Mastercard, Discover, and AMEX in the status quo, it’s difficult to picture the merged firm providing a deal so sweet that merchants would proactively encourage using cards on the Discover network over others, especially given the potential risk of losing customers who hold other cards. The merged firm would have to offer exceptionally low fees to entice merchants to proactively discourage using other card networks. Maybe they can get some merchants to offer a small discount for using cards on their network, but to accomplish that at a scale necessary to dent Visa’s and Mastercard’s omnipresence is difficult to imagine.

But there’s also a sneaky reason to expect that the merger might result in some higher merchant fees. As the American Economic Liberties Project’s Shahid Naeem said, the proposed deal is “an end-run around the Durbin Amendment and will raise fees for American businesses and consumers.” The Durbin Amendment is a component of the Dodd-Frank Act that caps transactions on debit card transaction fees, which merchants pay to the debit card issuers, at $0.21. However there are two built-in exceptions; (1) for debit issuers with less than $10 million in assets; and (2) as Marc Rubenstein pointed out, for Discover, by name. And Capital One has been clear that they want to move all their debit cards over to Discover’s network, which could make all Capital One debit cards eligible for higher fees to merchants.

Moreover, we already have a case study of how a single firm acting as issuer and processor might pan out: American Express already operates as a vertically integrated card issuer-payment processor, and AMEX charges higher merchant fees than Visa or Mastercard. So we shouldn’t expect vertical integration to automatically result in reduced merchant fees.

Be Skeptical of Purported Benefits to Cardholders

Likewise the merged firm could pass along any savings from avoided processing fees to cardholders in the form of lower interest rates. But there’s not much reason to expect that either: Recall that the horizontal aspect of the merger places upward pressure on rates for subprime customers. Any efficiencies flowing from reduced processing costs would have to overcome that upward price pressure.

The issue with any arguments about passing savings from processing costs onto cardholders is that they misunderstand the mechanism by which interest rates are set. Interest rates, both on credit cards and other types of loans, are primarily a function of the cost of borrowing at a given time (the “Prime rate”) plus a markup (the “APR margin”). The cost of borrowing is largely dependent on where the Fed sets interest rates. Hence, processing costs do not tend to enter the pricing calculus for annual credit card interest rates (which are invariant to the number of transactions). Further, a recent report from the CFPB shows that larger card issuers charge 8-10 percent higher interest rates than smaller credit card issuers, suggesting that cost efficiency actually results in higher interest rates for cardholders, not lower. The base interest rate controlled by the Fed is exogenous to all of this; the only question is how much of a premium the lender will charge.

Based on that finding, there are a couple of reasons why the merged firm would be likely to keep premiums over the Fed rates (and hence credit card interest rates) generally high, rather than pass savings on to consumers. To start, the emphasis on subprime lending creates more reason for higher markups; subprime borrowers are considered riskier, so they usually have to pay more to borrow to cover the increased odds of missing repayment. Additionally, because subprime lenders have more limited choices and because that’s the market segment Discover and Capital One both target, the merged firm’s share of subprime credit card issuing will likely require less competition than prime credit card issuing, allowing them to offer worse borrowing terms.

Be Skeptical of Other Purported Merger Benefits

Capital One further claims that the merger would make the combined firm a more potent competitor to Visa and Mastercard, potentially causing the two behemoths to reduce their own merchant fees. But this dynamic is frustrated for three reasons: built-in advantages to Visa’s and Mastercard’s business models, friction in transferring cards onto the Discover network, and disproportionate impacts on Mastercard and Visa that might actually leave only one dominant card processor.

First, Visa and Mastercard partner with lots (like lots and lots) of financial institutions rather than issuing their own cards. And that could give them a lot of advantages over Capital One/Discover. For one thing, people shop around for credit cards to varying extents. Some people look for cards with no annual fees, others make selections based off of perks like airline miles, and some people just get credit cards from the institutions they frequent. Where Mastercard and Visa really get a lot of their strength is from the partner institutions that issue the cards on their networks. This includes consumer-facing banks, credit unions, and financial institutions as well as retailers. And that comes with a lot of in-built advantages. For a start, it allows Visa and Mastercard to share responsibility on offerings like customer service with the issuer. If you go to your credit union and get their Visa credit card, you don’t need to direct every question you have to a Visa call center; many times you can call your credit union and they can answer your questions. That is both convenient and it can foster a larger degree of trust in the card, especially when the issuer is something like a credit union or local bank with whom depositors have a long history.

But there’s another, possibly even stronger, advantage to the Visa/Mastercard model–people can get cards with brand-specific rewards. Imagine you’re a contractor who buys a lot of supplies from Home Depot. The idea of a card that rewards you specifically for spending money at Home Depot could be very tempting, especially because you can often apply for it on your phone right in the store. Or if you shop at Costco, you might get a Costco card. If you travel, maybe you’d like a Southwest or American Airlines rewards card. You can get a Visa or Mastercard for any of those brands and many more. Capital One could try to set up similar partnerships, but that would likely come at the expense of their own card issuing, which is and would continue to be even after the merger, the biggest part of its business.

Second, the argument that the merger will create a more potent rival to Visa and Mastercard depends on the possibility of moving many or all of the credit cards issued by Capital One onto their in-house Discover network. That can be done, but it could well be a mess. Moving significant consumer credit accounts from one payment network to another is a big undertaking and, when it’s been done in the past, has caused major issues including consumers being unable to access their accounts or experiencing a big hit to their credit rating.

Plus there’s something of a catch 22 involved in migrating credit cards from one payment network to another. If Capital One is aggressive in transferring all of its cards onto Discover, then the odds that they actually could save on lower operating costs are much better. Fees for using a payment network are a major cost for card issuers. Moving aggressively also creates more opportunities for fatal mistakes, however, like damaging customers’ credit. On the flip side, Capital One moving only a few of its cards over would give more transition time, but would require them to continue paying fees to Visa and Mastercard without truly becoming a competitor. Either route could also complicate efforts to create rewards programs that rival Visa’s and Mastercard’s programs; other companies may not be eager to participate given uncertainty around how the transfer will play out.

Finally, if Capital One moved all of its cards over to the Discover network, it could usurp about 10 percent of Visa’s transaction volume and around 25 percent of Mastercard’s (Capital One has a lot of cards on both, but Visa has a much larger pool of other issuers’ cards on its network, so Capital One represents a markedly smaller share of traffic on their network). As of 2022, Visa’s network had 385 million cards, Mastercard’s had 309 million, and Discover’s had 75 million. That means that the new distribution (assuming the transaction volume is distributed roughly evenly across cards on all the processing networks) could look like Visa with 347 million, Mastercard with 232 million, and Discover with 191 million.

If that’s how it plays out, there’s some risk that Capital One/Discover would actually cement Visa’s advantage even more. Sure, Visa loses some 39 million cards, but Mastercard, which is already the smaller of the two, loses twice that. So, more than anything, it could be that the one true rival to Visa is weakened, leading a duopoly to become a monopoly. As far as how that impacts market share, Visa would go from 46 percent to 42 percent, Mastercard would plummet from 37 percent to 28 percent, and Discover would jump from 9 percent to 23 percent (for simplicity, AMEX is being treated as exogenous), as shown in the charts below.

And if that’s how it plays out, it could give Mastercard or American Express an opening to try and merge with each other or with other payment networks (i.e. PayPal or Klarna) and pitch it as the only way to preserve any true competition with Visa. The argument there is basically two pronged. First, Mastercard and AMEX are weaker and much less competitive, so they need a leg up to survive. Second, Capital One got to merge, so shouldn’t they? This is a common tactic corporations use in concentrated markets to justify even further concentration. See, for example, airlines.

The Merger Is Likely Anticompetitive On Net

That’s a lot to digest, but broadly, there are six things that need to be kept in mind when evaluating the Capital One/Discover merger:

- The merger will have impacts across multiple types of financial products. The two biggest are credit card issuing and credit card payment processing.

- Both Capital One and Discover focus largely on subprime borrowers. That means that, even though concentration in the issuer space may not generally be an issue, it could be much worse for those with the least access to credit already.

- Even for cardholders who do not consider interest rates while selecting a card, card issuers do compete on rewards programs, security measures, annual fees, and other features that could be gutted if a company has the market share to get away with it.

- Capital One is donning a veneer of consumer champion, mostly by claiming that it will be able to compete more effectively with Visa and Mastercard.

- Capital One’s ability to compete with Mastercard and Visa is complicated by a number of factors, including built-in advantages to Visa and Mastercard’s existing partnerships and friction in transferring Capital One cards to Discover.

- Even in the event that the merger does weaken Visa and Mastercard, it would likely asymmetrically harm Mastercard, potentially making Visa even more dominant.

The proposed merger between Capital One and Discover is complicated for a lot of reasons. Both companies offer an assortment of financial services (see this handy list from US News and World Report). Consequently, the merger will send ripples throughout an array of different banking and financial markets. Yet the meat of the deal centers on credit card issuing and payment processing. Ultimately, there are a lot of reasons why claims about Capital One’s acquisition of Discover being beneficial for consumers should be taken with a grain of salt. There are a lot of antitrust concerns, whether focusing on the card issuer space or payment processing. In particular, the deal would combine two of the largest subprime credit card issuers and could lead to worse terms for subprime borrowers. On the network side, while there is some possibility that Capital One could make the Discover network competitive with Visa and Mastercard, it could just as easily flounder or even make things worse by weakening Mastercard disproportionately. Between all of these competitive harms and other issues, plus concerns around community reinvestment (a concern raised here) and other past regulatory issues (especially recent probes of Discover), this deal could cause serious harm and deserves to face rigorous scrutiny moving forward.

Although the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is ostensibly an “independent agency,” its chair, Lina Khan, has been authorized by President Biden to destroy capitalism. Chair Khan has hijacked trade policy along with left-wing groups. Her approach to Amazon—a subject from which she should recuse her herself as she wrote an article on Amazon in law school—borders on brain-death and is incredibly weak. Her takes are so bad, you could make a killing betting against her. She could learn a thing or two about monopoly power from watching Shark Tank. Honestly, she keeps whiffing.

Let’s just take one example, the FTC’s case against Amgen. The FTC really went wild at first, but then its bark turned out worse than its bite. So we’re not sure where we come out here. Too much, too little? Hard to say. We blame Chair Khan for our confusion.

Chair Khan keeps chalking up defeats. We think that’s because Khan can’t see the future. Yet she keeps going back to the future.

She is against business, despite her gift to Netflix. And her gift to Walmart and Amazon. Don’t ask us why she’s giving Amazon a gift when she hates Amazon. But Walmart is still taking her on. Regardless, she’s conspiring with foreigners to hamstring U.S. companies. And she’s in the hands of “Big Labor,” which makes her a socialist.

Also, she is literally trying to kill you. It’s so unholy. Seriously, a monopoly can be life-saving! Her decisions have deadly consequences.

Quite frankly, she will grab power wherever she can. Flying too close to the sun can cause you to head for legal trouble.

Of course, the consumer-friendly patriots at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce will fight her. And fight her. Some are tired of fighting her, and have made noisy exits. Which we think show how abusive Chair Khan is. And abusive to staff, too. They are disgruntled. Even Lefties attack her.

Private equity warns her pro-enforcement stance hurts consumers. Really blasted her for that. Because as you know, mergers are pro-consumer, despite what overzealous folks like Chair Khan say. Businesses are really between a rock and Lina Khan’s FTC.

Did we mention that Chair Khan is biased? Against Amazon. Even though she narrowed her sights on them. And against Facebook. She has a Meta Fixation. Thanks to us, she can’t engage in a recusal coverup from all her biases.

Josh Hawley, have you met Lina Khan? Hawley loves Khan, but we don’t. Congress needs to investigate her.

We will say one positive thing about “Ms. Khan,” as we refer to her in an endearing and not-at-all misogynistic way: “Losing doesn’t get her down.” She’s “Taking on the World’s Biggest Tech Companies—and Losing.” Even if it MEANS losing. We think the point we are trying to make is she’s suffered so many setbacks. Yet all this losing is somehow intimidating, even causing a CEO to resign. All the while harassing Elon Musk.

What if she were around when the typewriter was invented? We don’t know, but we do know if she drives, she’ll try to fix her car even if it ain’t broke.

We think it is clear from what we’ve said here that Lina Khan hates business. Because of her and business-hating bureaucrats like her, businesses lack a seat at the table. In essence, corporate America is a political orphan. It’s spurring companies to rethink mergers, because her approach is not a Borkian “light touch.”

She hallucinates. She thinks all mergers are bad too. Biden needs to fix antitrust and rethink her ideas. Hashtag: Not all mergers. Chair Khan is too young and prone to radical ideas. Unlike the Chamber of Commerce, which is old. Oh, if only she didn’t fight the truth of Consumer Welfare! Then she wouldn’t be tempted to take such bad cases. Or any at all, really.

Bottom line. We hate her. Also, is there another U.S. antitrust enforcement agency manned by a man? We forget.

The views expressed here do not represent those of the author’s employers. The author decided to summarize the Wall Street Journal’s position on Lina Khan through its op-eds, editorials, and letters to the editor. There are so many. But he’s summarized the gist in this essay to save you time in the future. You’re welcome.

Articles Used for This Summary:

- The Story Behind Biden’s Trade Failure: Emails show how Lina Khan and the left co-opted Katherine Tai.

- Brain Death at the FTC and FCC: Net neutrality and Amazon show why Congress needs to kill agencies as well as creating new ones.

- Lina Khan Has a Weak Case Against Amazon: The FTC Chair defines monopoly down to harpoon the giant retailer with an antitrust suit.

- The Hedge Fund That Made a Killing Betting Against Lina Khan: Pentwater Capital predicted that FTC attempts to block big deals would fail

- Lina Khan Needs to See ‘Shark Tank’: Kevin O’Leary would never invest in a business that had to face conditions of ‘perfect competition.’

- Lina Khan Whiffs Again

- Antitrust Gone Wild Against Amgen: No theory is too strange for Lina Khan’s FTC to block a merger.

- Biden FTC’s Antitrust Bark Proves Worse Than Its Bite: FTC settlement with Amgen will pave way for more healthcare deal making

- Lina Khan Chalks Up Another Defeat: A federal judge tosses the FTC’s Meta suit as lacking enough evidence.

- The FTC Can’t See the Future: The agency litigates videogame consoles, which will be irrelevant in 10 years.

- Lina Khan and the FTC Go Back to the Antitrust Future: Biden’s reactionary trustbuster seeks to resurrect precedents that were out of date 40 years ago.

- Lina Khan’s Gift to Netflix; Blocking the Amazon-MGM deal would help the streaming giants.

- The FTC’s Grocery Gift to Walmart and Amazon: Chair Lina Khan won’t let Kroger and Albertsons merge to become more competitive.

- Walmart Takes On Lina Khan: A dubious FTC lawsuit tees up the agency for a constitutional challenge.

- The FTC Is Working With the EU to Hamstring U.S. Companies: Chair Lina Khan wants foreign help to impose her agenda that Congress wouldn’t pass.

- Lina Khan’s Non-Compete Favor to Big Labor

- Lina Khan Blocks Cancer Cures: Illumina’s acquisition of Grail would save lives, and it’s crazy for the FTC to call it a monopoly.

- The FTC’s Unholy Antitrust Grail: The agency overrules its own law judge to block Illumina’s acquisition.

- One ‘Monopoly’ That Could Save Your Life: Will Lina Khan’s FTC block widespread early detection of pancreatic cancer?

- Lina Khan’s Merger Myopia Has Deadly Consequences: Will a new cancer screening test become widely available?

- Lina Khan’s Power Grab at the FTC: The new Chair snatches unilateral authority and rescinds bipartisan Obama-era standards.

- Lina Khan Is Icarus at the FTC

- The FTC Heads for Legal Trouble: Its aggressive rule-making will create opportunities for judges to rein in the commission’s authority.

- Business Group Challenges Lina Khan’s Agenda at Federal Trade Commission

- The Chamber of Commerce Will Fight The FTC

- Why I’m Resigning as an FTC Commissioner: Lina Khan’s disregard for the rule of law and due process make it impossible for me to continue serving.

- The Many Abuses of Lina Khan’s FTC: Christine Wilson’s resignation highlights the agency’s bad turn.

- Lina Khan’s Trumpian Precedent

- Lina Khan Sees Turbulent Start as Head of Federal Trade Commission: Criticized by Republicans, Khan tells agency staffers she aims to build bridges going forward

- Progressives Attack Their Own at the FTC

- Antitrust Attacks on Private Equity Hurt Consumers

- Private Equity Blasts Antitrust Agencies’ Efforts to Slow Mergers

- T-Mobile Proves That Mergers Can Benefit Consumers: That should give pause to today’s overzealous antitrust enforcers.

- Between a Rock and Lina Khan’s FTC

- Amazon Seeks Recusal of FTC Chairwoman Lina Khan in Antitrust Investigations of Company

- Lina Khan Once Went Big Against Amazon. As FTC Chair, She Changed Tack.

- Facebook Seeks FTC Chair Lina Khan’s Recusal in Antitrust Case

- Lina Khan Has a Meta Fixation

- Lina Khan’s Recusal Coverup

- Josh Hawley, Meet Lina Khan

- Josh Hawley Loves Lina Khan

- Congress Can Investigate Lina Khan

- Lina Khan’s Artificial Intelligence: Fresh off its latest legal defeat, the FTC moves to regulate ChatGPT.

- Lina Khan Is Taking on the World’s Biggest Tech Companies—and Losing

- Why the FTC’s Lina Khan Is Taking on Big Tech, Even if It Means Losing

- Antitrust Regulation by Intimidation

- Lina Khan Wins as Illumina’s CEO Resigns

- The Harassment of Elon Musk

- If Lina Khan Had Been Around When the Typewriter Was Invented

- Car Shopping Ain’t Broke, So the FTC Will Fix It

- How Corporate America Became a Political Orphan

- Wall Street Deal Making Faces Greater Scrutiny, Delays Under FTC’s Lina Khan

- The Return of the Trustbusters

- Forget AI: The Administrative State Is a Bad Algorithm: Microsoft trustbusters and EPA regulators show chatbots aren’t the only ones who ‘hallucinate.’

- How Biden Can Get Antitrust Right: New draft competition guidelines released last week need revision. Not all mergers are bad.

- Let a Biden Reappraisal Include Antitrust: If any good comes from the administration’s debacles, our oldest president will put aside childish things.

- The New Progressives Fight Against Consumer Welfare

- Lina Khan and Amy Klobuchar’s Microsoft Temptation

Healthcare in rural America has hit a crisis point. Although the health of people living in rural areas is worse than those living in metropolitan areas, rural populations are deprived of the healthcare services they deserve and need. Rural residents are more likely to be poor and uninsured than urban residents. They are also more likely to suffer from chronic conditions or substance-abuse disorders. Rural communities also experience higher rates of suicide than do communities in urban areas.

For people of color, life in rural America is even harder. Research demonstrates that racial and ethnic minorities in rural areas are less likely to have access to primary care due to prohibitive costs, and they are more likely to die from a severe health condition, such as diabetes or heart disease, compared to their urban counterparts.

Although rural residents in America experience worse health outcomes than urban residents, rural hospitals are closing at a dangerous rate. Rural hospitals experience a severe shortage of nurses and physicians. They also treat more patients who rely on Medicaid and Medicare, or who lack insurance altogether, which means that they offer higher rates of uncompensated care than urban hospitals. For these reasons, hospitals in rural areas are more financially vulnerable than hospitals in metropolitan areas.

Indeed, recent data show that since 2005, more than 150 rural hospitals have shut their doors and more than 30% of all hospitals in rural areas are at immediate risk of closure. As hospital closures in rural America increase, the areas where residents lack geographic access to hospitals and primary care physicians, or “hospital deserts,” also increase in size and number.

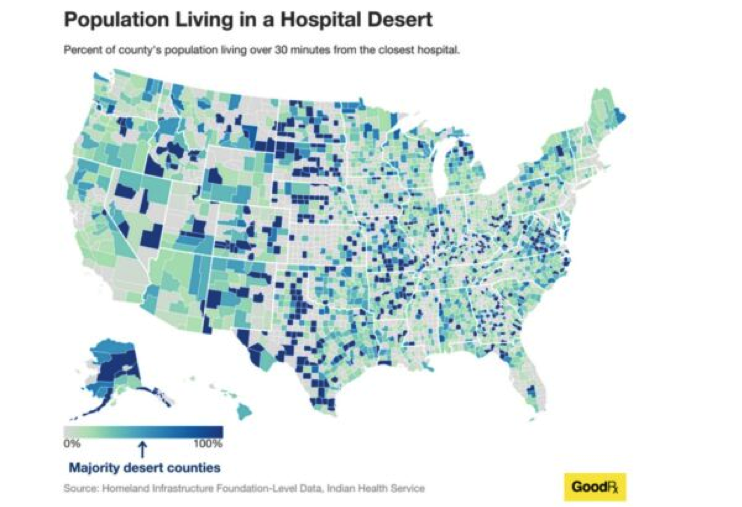

This map is illustrative. It indicates two important things. First, in more than 20% of American counties, residents live in a hospital desert. Second, hospital deserts are primarily located in rural areas.

Empirical evidence demonstrates that hospital deserts reduce access to care for rural residents and exacerbate the rising health disparities in America. When a hospital shuts its doors, rural residents must travel long distances to receive any type of care. Rural residents, however, tend to be more vulnerable to overcoming these obstacles, as some of them do not even have access to a vehicle. For this reason, data show that rural residents often skip doctor appointments, delay necessary care, and stop adhering to their treatment.

Despite the magnitude of the hospital deserts problem and the severe harm they inflict on millions of Americans, public health experts warn that rural communities should not give up. For instance, Medicaid expansion and increased use of telemedicine can increase access to primary care for rural residents and thus can improve the financial stability of rural hospitals. When people lack access to primary care due to lack of coverage, they end up receiving treatment in the hospitals’ emergency departments. For this reason, research shows, rural hospitals offer very high rates of uncompensated care, which ultimately contributes to their closure.

This Antitrust Dimension of Hospital Deserts in Rural America

In a new piece, the Healing Power of Antitrust, I explain that these proposals, albeit fruitful, may fail to cure the problem. The problem of hospital deserts is not only the result of the social and demographic characteristics of rural residents, or the increased level of uncompensated care rural hospitals offer. The hospital deserts that plague underserved areas are also the result of anticompetitive strategies employed by both rural and urban hospitals. These strategies, which include mergers with competitors and non-competes in the labor market, eliminate access to care for rural populations and aggravate the severe shortage of nurses and physicians rural communities experience. In other words, these strategies contribute to hospital deserts in rural America. How did we get here?

In general, hospitals often claim that they need to merge with their competitors to cut their costs and improve their quality. Yet several hospitals often acquire their closest competitors in rural areas just to remove them from the market and increase their market power both in the hospital services and the labor markets.

For this reason, after the merger is complete, the acquiring hospitals shut down the newly acquired ones. This buy-to-shutter strategy has had a devastating impact on the health of rural communities who desperately need treatment. For instance, data show that each time a rural hospital shuts its doors, the mortality rate of rural residents significantly increases.

Even in cases where hospital mergers do not lead to closures, they still reduce access to care for the most vulnerable Americans—lower income individuals and communities of color. For instance, a recent study indicates that post-merger, only 15% of the acquired hospitals continue to offer acute care services. Other studies show that after the merger is complete, the acquiring hospitals often move to close essential healthcare services, such as maternal, primary, and surgical care.

When emergency departments in underserved areas shut down, the mental health of rural Americans deteriorates at dangerous rates. For rural Americans who lack coverage, entering a hospital’s emergency department is the only way they can gain access to acute mental healthcare services and substance abuse treatment. Not surprisingly, studies reveal that over the past two decades, the suicide rates for rural Americans have been consistently higher than for urban Americans.

But this is not the only reason why mergers among hospitals in rural areas contribute to the hospital closure crisis. Mergers also allow hospitals to increase their market power in input markets, most notably labor markets, and even attain monopsony power, especially if they operate in rural areas where competition in the hospital industry is limited.

This allows hospitals to suppress the wages of their employees and to offer them employment under unfavorable working conditions and employments terms, including non-competes. This exacerbates the severe shortage of nurses and physicians that rural hospitals are experiencing and, ultimately, contributes to their closures.

Empirical research validates these concerns. A recent study that assessed the relationship between concentration in the hospital industry and the wages of nurses in America reveals that mergers that considerably increased concentration in the hospital market slowed the growth of wages for nurses. Other surveys show that post-merger nurses and physicians experience higher levels of burnout and job dissatisfaction, as well as a heavier workload.

These toxic working conditions become almost inescapable when combined with non-compete clauses. By reducing job mobility, non-competes undermine employers’ incentives to improve the wages and the working conditions of their employees. Sound empirical studies illustrate that these risks are real. For instance, a leading study measuring the relationship between non-competes and wages in the U.S. labor market concludes that decreasing the enforceability of non-competes could increase the average wages for workers by more than 3%. Other surveys reveal that non-competes in the healthcare industry contribute to nurses’ and physicians’ burnout, encouraging them either to leave the market or seek early retirement at increasing rates. This premature exit also exacerbates the shortage of nurses and physicians that is hitting rural America.

Moreover, by eliminating job mobility, non-competes imposed by rural hospitals prevent nurses and physicians from offering their services in competing hospitals in underserved areas, which already struggle to attract workers in the healthcare industry and meet the increased needs of their patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated this problem. When, in the midst of the pandemic, there was a surge of COVID patients, many hospitals lacked the necessary medical staff to meet the demand. For this reason, several hospitals were forced to send patients with severe symptoms back home, leaving them without essential care. This likely contributed to the high mortality rates rural America experienced during the COVID 19 pandemic.

Given these risks, my article asks: Can antitrust law cure the hospital desert problem that harms the health and well-being of rural residents? It makes three proposals.

Proposal 1: Courts should examine all non-competes in the healthcare sector as per se violations of section 1 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits any unreasonable restraints of trade.

Per se illegal agreements are those agreements under antitrust law which are so harmful to competition and consumers that they are unlikely to produce any significant procompetitive benefits. Agreements not condemned as illegal per se are examined under the rule-of-reason legal test, a balancing test that the courts apply to weigh an agreement’s procompetitive benefits against the harm caused to competition. When applying the rule-of-reason test, courts generally follow a “burden-shifting approach.” First, the plaintiff must show the agreement’s main anticompetitive effects. Next, if the plaintiff meets its initial burden, the defendants must show that the agreement under scrutiny also produces some procompetitive benefits. Finally, if the defendant meet its own burden, the plaintiff must show that the defendant’s objectives can be achieved through less restrictive means.

To date, courts have examined all non-compete agreements in labor markets under the rule-of-reason test on the basis that they have the potential to create some procompetitive benefits. For instance, reduced mobility might benefit employers to the extent it allows them to recover the costs of training their workers and reduces the purported “free riding” that may occur if a new employer exploits the investment of the former employer.

Applying the rule-of-reason test in the case of non-competes, especially in the healthcare industry, is a mistake for at least two reasons. First, because hospitals do not appreciably invest in their workers’ education and training, there is little risk of such investment being appropriated. Hence, the claim that non-competes reduce the free riding off non-existent investment is simply unconvincing.

Second, because the rule-of-reason legal test is an extremely complex legal and economic test, the elevated standard of proof naturally benefits well-heeled defendants. This prevents nurses and physicians from challenging unreasonable non-competes, which ultimately encourages their employers to expand their use, even in cases where they lack any legitimate business interest to impose them.

Importantly, the federal agencies tasked with enforcing the antitrust laws, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), have not shut their ears to these concerns. Specifically, the FTC has proposed a new federal regulation that aims to ban all non-compete agreements across America, including those for physicians and nurses. Considering the severe harm non-competes in the healthcare sector cause to nurses, physicians, patients, and ultimately public health, this is a welcome development.

Proposal 2: Antitrust enforcers and the courts should start assessing the impact of hospital mergers on healthcare workers’ wages and working conditions

My article also argues that hospital mergers should be assessed with workers’ welfare at top of mind. Failing to do so will exacerbate the problem of hospital deserts, which so profoundly harms the lives and opportunities for millions of Americans. As noted, mergers allow hospitals to further increase their market power in the labor market. The removal of outside work options allows hospitals to suppress their workers’ wages and to offer employment under unfavorable terms, including non-competes. This encourages nurses and physicians to leave the market at ever increasing rates, which magnifies the severe shortage of nurses and physicians hospitals in rural communities are experiencing and contributes to their closures.

Despite these effects, thus far, whenever the enforcers assessed how a hospital merger may affect competition, they mainly focused on how the merger impacted the prices and the quality of hospital services. So how would the enforcers assess a hospital merger’s impact on labor?

First, enforcers would have to define the relevant labor market in which the anticompetitive effects—namely, suppressed wages and inferior working conditions—are likely to be felt. Second, enforcers would have to assess how the proposed merger may impact the levels of concentration in the labor industry. If the enforcers showed that the proposed merger would substantially increase concentration in the labor market, they would have good reason to stop the merger.

In response to such a showing, the merging hospitals might claim that the merger would create some important procompetitive benefits that may offset any harm to competition caused in the labor market. For instance, the hospitals may claim that the merger would allow hospitals to reduce the cost of labor and, hence, the rates they charge health insurers. This would benefit the purchasers of health insurance services, notably the employers and consumers. But should the courts be convinced by such a claim of offsetting benefits?

Not under the Supreme Court’s ruling in Philadelphia National Bank. There, the Supreme Court made clear that the procompetitive justifications in one market cannot outweigh its anticompetitive effects in another. For this reason, the courts could argue that any benefits the merger may create for one group of consumers—the purchasers of health insurance services—cannot outweigh any losses incurred by another group, the workers in the healthcare industry.

Proposal 3: Antitrust enforcers should accept hospital mergers in rural areas only under specific conditions

My article contends that such mergers should be condoned only under the most stringent of circumstances. Specifically, enforcers should accept mergers in rural areas only under the condition that the merged entity agrees to not shut down facilities or cut essential healthcare services in underserved areas.

Conclusion

Has antitrust law failed workers in the healthcare industry and ultimately public health? Given the concerns expressed above, the answer is unfortunately, yes. By failing to assess the impact of hospital mergers on the wages and the working conditions of employees in the hospital industry, and by examining all non-competes in labor markets under the rule-of-reason legal test, the courts have contributed to the hospital desert problem that disproportionately affects vulnerable Americans. If they fail to confront this crisis, the courts also risk contributing to the racial and health disparities that undermine the moral, social, and economic fabric in America.

Theodosia Stavroulaki is an Assistant Professor of Law at Gonzaga University School of law. Her teaching and research interests include antitrust, health law, and law and inequality. This piece draws on her article “The Healing Power of Antitrust” forthcoming in Northwestern University Law Review 119(4) (2025)

In condemning Nippon Steel’s proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel, many politicians, from John Fetterman to Donald Trump, are ignoring the severe costs of the alternative tie-up with a domestic steel-making rival—the harms to competition in both labor and product markets from the alternative merger with Cleveland-Cliffs (the “alternative merger”). Whatever security concerns might flow from ceding control of a large steel operation to a Japanese company must be assessed against the likely antitrust injury that would be inflicted on domestic workers and steel buyers by combining two direct horizontal competitors in the same geographic market. This basic economic point has been lost in the kerfuffle.

Harms to Labor

The first place to consider competitive injury from the alternative merger is the labor market, in which Cleveland-Cliffs and U.S. Steel compete for labor working in mines. If Cleveland-Cliffs (“Cliffs”) had been selected by U.S. Steel, there would only be one steel employer remaining in some geographic markets such as northern Minnesota and Gary, Indiana. This consolidation of buying power would have reduced competition in hiring of steel workers, almost certainly driving down workers’ wages by limiting their mobility.

To wit, Minnesota’s Star Tribune noted that “Cleveland-Cliffs and U.S. Steel have long histories on Minnesota’s Iron Range, controlling all six of the area’s taconite operations. Cliffs fully owns three of the six taconite mines, and U.S. Steel owns two.” Ownership of the sixth mine is shared between Cliffs (85%) of U.S. Steel (15%). A Cliffs/U.S. Steel merger also would have made the combined company the sole industry employer in the region surrounding Gary, per the American Prospect. Additional harms from newfound buying power include reduced jobs and greater control over workers who retain their jobs.

The newly revised DOJ/FTC Merger Guidelines explain that labor markets are especially vulnerable to mergers, as workers cannot substitute to outside employment options with the same ease as consumers substituting across beverages or ice cream. But the harm to labor here is not merely theoretical: A recent paper by Prager and Schmitt (2021) found that mergers among hospitals had a substantial negative effect on wages for workers whose skills are much more useful in hospitals than elsewhere (e.g., nurses). In contrast, the merger had no discernible effect on wages for workers whose skills are equally useful in other settings (e.g., custodians). A paper I co-authored with Ted Tatos found labor harms from University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s acquisitions of Pennsylvania hospitals. And Microsoft’s recent acquisition of Activision was immediately followed by the swift termination of 1,900 Activision game developers, a fate that was predictable based on the combined firm’s footprint among gaming developers, as well job-switching data between Microsoft and Activision.

This is the type of harm that the U.S. antitrust agencies would almost assuredly investigate under the new antitrust paradigm, which elevates workers’ interests to the same level as consumers’ interests. Indeed, the Department of Justice recently blocked a merger among book publishers under a theory of harm to book authors. Under Lina Khan’s stewardship, the Federal Trade Commission is likely searching for its own labor theory of harm, potentially in the Kroger-Albertsons merger.

And the Nippon acquisition would largely avoid this type of harm, as Nippon does not compete as intensively, compared to Cliffs, against U.S. Steel in the domestic labor market. To be fair, Nippon does have a small American presence: It has investments in several U.S. companies and employs (directly and indirectly) about 4,000 Americans—but far fewer than U.S. Steel (21,000 U.S. based employees) and Cliffs (27,000 U.S. based employees). Importantly, Nippon employs no steelworkers in Minnesota, and its plants in Seymour and Shelbyville, Indiana are roughly a three-hour drive from Gary.

It bears noting that United Steelworkers (USW), the union representing steelworkers, has come out against the Nippon/U.S. Steel merger, alleging that U.S. Steel violated the successorship clause in its basic labor agreements with the USW when it entered the deal with a North American holding company of Nippon. This opposition is not proof, however, that the alternative merger is beneficial to workers, or even more beneficial to workers than the Nippon deal. Recall that the union representing game developers endorsed Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision, which turned out to be pretty rotten for 1,900 former Activision employees. Sometimes union leaders get things wrong with the benefit of hindsight, even when their hearts are in the right place.

Harms to Steel Buyers

Setting aside the labor harms, the alternative merger would result in Cliffs becoming “the last remaining integrated steelmaker in the country.” Mini-mill operators like Nucor and Steel Dynamics do not serve some key segments served by integrated steelmakers, such as the market for selling steel to automakers. In particular, automakers cannot swap out steel made from recycled scrap at mini-mills with stronger and more malleable steel made from steel blast furnaces. According to Bloomberg, a combined Cliffs/U.S. Steel would become the primary supplier of coveted automotive steel.

The prospect of Cliffs acquiring U.S. Steel triggered the automotive trade association, the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, to send a letter to the leadership of the Senate and House subcommittees on antitrust, explaining that a “consolidation of steel production capacity in the U.S. will further increase costs across the industry for both materials and finished vehicles, slow EV adoption by driving up costs for customers, and put domestic automakers at a competitive disadvantage relative to manufacturers using steel from other parts of the world.”

Moreover, a U.S. Steel regulatory filing detailed how antitrust concerns in the output market factored in its decision to reject Cliffs’s bid. U.S. Steel’s proxy noted: “A transaction with [Cliffs] would eliminate the sole new competitor in non-grain-oriented steel production in North America as well as eliminate a competitive threat to [Cliffs’s] incumbent position in the U.S., and put up to 95% of iron ore production in the U.S. under the control of a single company.”

Once again, the lack of any material presence by Nippon in the United States ensures that such consumer harms are largely limited to the Cliffs tie-up. An equity research analyst with New York-based CFRA Research who follows the steel industry noted that Nippon has a “very small footprint currently in North America.”

Balancing Security Concerns Against Competition Harms

Regarding national security concerns from a Nippon-U.S. Steel tie-up, The Economist opined these harms are exaggerated: “A Chinese company shopping for American firms producing cutting-edge technology that could help its country’s armed forces should, and does, set off warning sirens. Nippon’s acquisition should not.” If the concern is control of a domestic steelmaker during wartime, the magazine explained, U.S. Steel’s operations “could be requisitioned from a disobliging foreign owner.” For the purpose of this piece, however, I conservatively assume that the security costs from a Nippon tie-up are economically significant. My point is that there are also significant costs to workers and automakers from choosing a tie-up with Cliffs, and sound policy militates in favor of measuring and then balancing those two costs.

Finally, this perspective is based on the assumption that U.S. Steel must find a buyer to compete effectively. Maintaining the status quo would evade both national security and competition harms implicated by the respective mergers. But if policymakers must choose a buyer, they should consider both the competition harms and the national security implications. Ignoring the competition harms, as some protectionists are inclined to do, makes a mockery of cost-benefit analysis.

Since the boycott of the U.S. News and World Report Rankings (“U.S. News Rankings”) by a group of law schools, the U.S. News Rankings have gone a bit haywire. The top law schools, all highly ranked, refused to submit data to U.S. News. Other schools followed their lead. As a result, U.S. News changed its rankings, perhaps focusing a bit more on publicly available data.

But that has led to speculation of potentially wild results. In the past, such dramatic ranking shifts were somewhat limited, but with the changing rankings, and the apparent new norm of frequent changes to methodologies, such radical changes might be in our future. It is striking, though, how the fluctuations rarely seem to affect the higher ranked schools.

Meanwhile, prospective law students, perhaps largely unaware of these fluctuations because the top-ranked law schools barely change, are likely still invested in the U.S. News Rankings for determination of what makes a good law school. A quick check assures that the schools they know are prestigious like Harvard and Yale are in the top ten, with little variation year to year.

And, despite the understanding in the legal academy about the inconsistency and other problems, the U.S. News Rankings are still used by some schools as an aspirational goal and a publication goal (with some schools offering anti-intellectual publication bonuses for high-rank placement). Others use the rankings for marketing materials to prospective faculty candidates and students.

In this essay, I list five problems with the U.S. News Rankings, and I offer a few concrete solutions.

Problem 1: Information Asymmetries between Prospective Students and U.S. News

Prospective students know little about the ranking methodology or its impact. For example, students may know what percentage of the rankings is based upon peer assessment, but not know that the peer assessment has problems, such as the monopoly power a few schools wield in the law professor labor market. Students likely do not know of relative changes in rankings over time, so are unable to determine whether a rapid change is a mere blip or a genuine trend downward or upward. In short, the prospective student may be deceived by the nature of the rankings and the changes in how rankings are calculated.

Problem 2: Information Asymmetries between the Law Schools and U.S. News

As the dominant player in the market for rankings, U.S. News has little incentive to expend resources to monitor the data that law schools provide, to correct inaccurate data, or to make algorithmic adjustments unless the results produced by its formula are egregiously false or schools flagrantly manipulate the data that they submit. In fact, the value of the rankings endures by virtue of having little change at the top of the list. Should a school experience an unexpected drop in ranking, however, dramatic effects may occur, including dean resignations. Schools seeking to climb the rankings to attract high-quality students, or faced with habitually low rankings, may succumb to pressure to manipulate data to improve their rank. For example, it has been past practice for schools to employ their former students to inflate post-graduation employment statistics.

Problem 3: Favoring Well-Endowed Schools

To the extent that U.S. News alters variables as to what makes a “good school,” it favors wealthier schools that can deploy more resources and adapt quickly to the moving goal posts. But those at the top end of the rankings do not need to worry, as they are virtually guaranteed their spot. Other schools are subject to the potential of rapid fluctuations.

Schools also make significant time investments by creating committees tasked with benchmarking competitive schools, collecting employment data from recent graduates, and grappling with the impact of how varying analyses of the information might affect the U.S. News Rankings.

Part of the methodological shift as such is the post-boycott need to access publicly available data. That need, however, may not be a great basis for the methodology put forward. It may merely be a streetlight effect on methodology road.

Problem 4: The Problem of Potential Retaliation

To the extent that the variables that inform U.S. News Rankings are subject to change, they are potentially subject to abuse. It would be easy to add variables punishing schools that complain about the ranking’s methodology.

Just two examples should suffice. When Reed College refused to provide data to U.S. News for the general college rankings, instead of omitting the institution from its ranking, U.S. News “arbitrarily assigned the lowest possible value to each of Reed’s missing variables, with the result that Reed dropped in one year from the second quartile to the bottom quartile.” In subsequent rankings, U.S. News allegedly ranked Reed College on information available from other sources, noting that the institution did not complete the requested survey. In the law school context, when Pepperdine discovered an error in its submission, it sought to correct it. As a result of its innocent mistake, its ranking plummeted for a year.

Problem 5: Lack of Competition in Rankings

There are no substitutes for U.S. News Rankings, at least for U.S. law schools. The vast majority of prospective students use them. The vast majority of schools look to them. To the extent it is a monopoly, it has a unique role in shaping legal education. Indeed, not only is it a unique ranking, much effort is made by Spivey Consulting and others to predict those rankings, rather than create new ones.

As Sahaj Sharda has pointed out in The Sling, rankings matter. And it is rife with the possibility of hijinks, both from the university side and from the side of U.S. News.

Solution: An FTC Unfair or Deceptive Act or Practice (UDAP) Rule

Section 5 of the FTC Act states that “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce . . . are . . . declared unlawful.” Deceptive acts or practices require a “material representation, omission or practice that is likely to mislead a consumer acting reasonably in the circumstances.” An act or practice is “unfair” if it “causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers which is not reasonably avoidable by consumers themselves and not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.”

The FTC UDAP rules cover common consumer experiences, such as wash-and-dry labels, octane ratings for gasoline, funeral prices, eyeglasses, auto fuel ratings, used cars, energy ratings, door-to-door sales, identity theft, free credit report, contact lenses and eyeglasses, and child protection. In each of these instances, informational and other barriers barred consumers from realizing important information or availing themselves of alternatives.

Why not apply the same principles to rankings? An FTC UDAP rule related to law school rankings could involve three components.

First, the FTC should require U.S. News to disclose the algorithm it uses or to explain in greater detail the amount of weight it puts on each factor that goes into its overall rankings. An algorithm is a mathematical formula that allows data factors to be compiled into an order, based on the relative importance of each input. If an end user has different values or priorities than U.S. News, the algorithm makes a major difference in the list’s outcome. Disclosing the algorithm protects the consumer from false, deceptive, and misleading information.

The FTC should mandate that any alteration of methodology should provide law schools with at least two year’s notice. At present, much of the methodology could be ex-post, surprising schools attempting to climb the rankings.

Second, the rule should eliminate conflict of interest voting and should mandate disclosure of other data. Schools are not in a position to rank themselves; nor are faculty of a school that is dominant in the production of law professors. The bulk of law professors hail from a few schools. Absent a horrific experience, it stands that the bulk of reputation scores favor those schools. This self-perpetuating cycle is not known to prospective students, and ought to be halted.

To the extent post-graduation employment is used, schools ought to be forced to disclose that number. Thus far, U.S. News has been reluctant and unable to determine the extent of such gaming. Subjecting such data submission to a UDAP rule raises the potential risk to a school that such manipulation might become subject to an investigation and an amplified public notice.

Third, the FTC’s rule should impose penalties on schools and U.S. News for violations of the rule. Another feature of a UDAP rule would be consistent deterrence, as opposed to arbitrary punishments that U.S. News might impose upon schools. If such penalties are not linked to the ranking itself, a UDAP rule would still benefit consumers of the ranking, whereas displacing the ranking of a school that misbehaves might penalize beyond the group involved in the decision to manipulate the ranking.

If the FTC were to adopt such a rule, it would bring some much-needed relief to law school applicants and the schools themselves.

The views expressed in this piece do not reflect the views of my employer.

Correction 2/28/24: Since publication, Spivey Consulting reached out to correct an entry error related to Buffalo Law School’s ranking in their post, when Spivey converted that information from their software to the blog. We have corrected the entry here as well. Other schools will still face such drops.

The news of the layoffs was stunning: Three months after consummating its $68 billion acquisition of Activision, Microsoft fired 1,900 employees in its gaming division. The relevant question, from a policy perspective, is whether these terminations reflect the exercise of newfound buying power made possible by the merger? If so, then Microsoft may have just unwittingly exposed itself to antitrust liability, as mergers can be challenged after the fact in light of clear anticompetitive effects.

The Merger Guidelines recognize that mergers in concentrated markets can create a presumption of anticompetitive effects. When studying the impact of a merger on any market, including a labor market, the starting place is to determine whether the merged firm collectively wielded market power in some relevant antitrust market. That inquiry can be informed with both direct and indirect evidence.

Direct evidence of buying power, as the name suggests, is evidence that directly shows a buyer has power to reduce wages or exclude rivals. Indirect evidence of buying power can be established by showing high market shares (plus entry barriers) in a relevant antitrust market. It bears noting that, when it comes to labor markets, high market shares are not strictly needed to infer buying power due to high search and switching costs (often absent in output markets).

Beginning with the direct evidence, Activision exhibited traits of a firm with buying power over its workers. For example, before it was acquired, Activision undertook an aggressive anti-union campaign against its workers’ efforts to organize a union. Moreover, workers at Activision complained about their employer’s intransigent position on granting raises, often demanding proof of an outside offer. A recent article in Time recounted that “Several former Blizzard employees said they only received significant pay increases after leaving for other companies, such as nearby rival Riot Games, Inc. in Los Angeles.” Activision also entered a consent decree in 2022 with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to resolve a complaint alleging Activision subjected its workers to sexual harassment, pregnancy discrimination, and retaliation related to sexual harassment or pregnancy discrimination.

Moving to the indirect evidence, one could posit a labor market for video game workers at AAA gaming studios. Both Microsoft and Activision are AAA studios, making them a preferred destination for industry labor. Independent studios are largely regarded as temporary stepping stones toward better positions in large video game firms.

To estimate the merged firm’s combined share in the relevant labor market, in a forthcoming paper, Ted Tatos and I study CareerBuilder’s Supply and Demand data, filtering on the term “video game” in the United States to recover job applications and postings over the last two years. The table summarizes the results of our search in the Spring 2022, a few months after the Microsoft-Activision deal was announced. Our analysis conservatively includes small employers that workers at a AAA studio such as Activision likely would not consider to be a reasonable substitute.

Job Postings Among Top Studios in Video Game Industry – CareerBuilder Data

| Company Name | Number of Job Postings | Percent of Postings | Corporate Entity |

| Activision Blizzard, Inc. | 1,270 | 26.0% | Microsoft |

| Electronic Arts Inc. | 856 | 17.5% | |

| Rockstar Games, Inc. | 287 | 5.9% | Take-Two |

| Ubisoft, Inc. | 258 | 5.3% | |

| 2k, Inc. | 143 | 2.9% | Take-Two |

| Zenimax Media Inc. | 128 | 2.6% | Microsoft |

| Epic Games, Inc. | 112 | 2.3% | |

| Lever Inc | 106 | 2.2% | |

| Wb Games Inc. | 101 | 2.1% | |

| Survios, Inc. | 100 | 2.0% | |

| Riot Games, Inc. | 91 | 1.9% | Tencent |

| Zynga Inc. | 84 | 1.7% | Take-Two |

| Funcom Inc | 79 | 1.6% | Tencent |

| 2k Games, Inc. | 74 | 1.5% | Take-Two |

| Complete Networks, Inc. | 65 | 1.3% | |

| Gearbox Software | 58 | 1.2% | Embracer |

| Digital Extremes Ltd | 43 | 0.9% | Tencent |

| Naughty Dog, Inc. | 43 | 0.9% | Sony |

| Mastery Game Studios, LLC | 26 | 0.5% | |

| Crystal Dynamics Inc | 25 | 0.5% | Embracer |

| Skillz Inc. | 25 | 0.5% | |

| Microsoft Corporation | 24 | 0.5% | Microsoft |

| Others | 887 | 18.2% | |

| TOTAL | 4,885 | 100.0% |

As indicated in the first row, Activision lies at the top in number of job postings in the CareerBuilder data, with 26.0 percent. Prior to the Activision acquisition, Microsoft accounted for 3.1 percent of job postings (the sum of Zenimax Media and Microsoft rows). Based on these figures, Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision significantly increased concentration (by more than 150 points) in an already concentrated market (post-merger HHI above 1,200). This finding implies that the merger could lead to anticompetitive effects in the relevant labor market, including layoffs.

It bears noting that the HHI thresholds established in the 2023 Merger Guidelines (Guideline 1) were most likely developed with product markets in mind. Indeed, the Guidelines recognize in a separate section (Guideline 10) that labor markets are more vulnerable to the exercise of pricing power than output markets: “Labor markets frequently have characteristics that can exacerbate the competitive effects of a merger between competing employers. For example, labor markets often exhibit high switching costs and search frictions due to the process of finding, applying, interviewing for, and acclimating to a new job.” High switching costs are also present in the video game industry: Almost 90 percent of workers at AAA studios in the CareerBuilder Resume data indicate that they did not want to relocate, making them more vulnerable to an exercise of market power than the HHI analysis above implies.

As any student of economics recognizes, a monopsonist not only reduces wages below competitive levels, but also restricts employment relative to the competitive level. So the immediate firing of 1,900 workers is consistent with the exercise of newfound monopsony power. In technical terms, the layoffs could reflect a change in the residual labor supply curve faced by the merged firm.

Why would Microsoft exercise its newfound buying power this way? To begin, many Microsoft workers, prior to the merger, could have switched to Activision in response to a wage cut. Indeed, we were able find in the CareerBuilder data that a substantial fraction of former Microsoft workers left Microsoft Game Studios to work for Activision. (More details on the churn rate to come in our forthcoming paper.) Post-merger, Microsoft was able to internalize this defection, weakening the bargaining position of its employees, and putting downward pressure on wages. In other words, Microsoft is more disposed to cutting Activision jobs than would a standalone Activision. Moreover, by withholding Activision titles from competing multi-game subscription services—the FTC’s primary theory of harm in its litigation, now under appeal—Microsoft can give an artificial boost to its platform division. This input foreclosure strategy would compel Microsoft to downsize its gaming division and thus its gaming division workers.

Alternative Explanations Don’t Ring True

The contention that these 1,900 layoffs flowed from the merger, as opposed to some other force, is supported in the economic literature in other labor markets. A recent paper by Prager and Schmitt (2021) studied the effect of a competition-reducing hospital merger on the wages of hospital staff. Consistent with economic theory, the merger had a substantial negative effect on wages for workers whose skills are much more useful in hospitals than elsewhere (e.g., nurses). In contrast, the merger had no discernable effect on wages for workers whose skills are equally useful in other settings (e.g., custodians). As Hemphill and Rose (2018) explain in their seminal Yale Law Journal article, “A merger of competing buyers can exacerbate the merged firm’s incentive to buy less in order to drive down input prices.”

Microsoft has its defenders in academia. According to Joost van Dreunen, a New York University professor who studies the gaming business, the video game industry is “suffering through a winter right now. If everybody around you is cutting their overhead and you don’t, you’re going to invoke the wrath of your shareholders at some point.” (emphasis added) This point—which sounds like it was fed by Microsoft’s PR firm—is intended to suggest that the firings would have occurred absent the merger. But there are two problems with this narrative. First, Microsoft’s gaming revenues are booming (up nine percent in the first quarter of its 2024 fiscal year), which makes industry comparables challenging. What were the layoffs among video game firms that also grew revenues by nine percent? Second, video programmers and artists are not “overhead,” such as HR workers or accountants. (Apologies to those workers.) Thus, their firing cannot be attributed to some redundancy in deliverables.

Microsoft’s own press statement about the layoffs vaguely states that it has “identified areas of overlap” across Activision and its former gaming unit. But that explanation is just as consistent with the labor-market harm articulated here as with the “eliminating redundancy” efficiency.

Bobby Kotick, the former CEO of Activision, received a $400 million golden parachute at the end of the year for selling his company to Microsoft. That comes to about $210,500 per fired employee, or about two years’ worth of severance for each worker laid off. Too bad those resources were so regressively assigned.

Larry Summers and other corporate apologists asserted for over a year that the Federal Reserve would have to engineer a recession to bring down prices. But as inflation continues to fall with no corresponding rise in unemployment, doomsayers’ insistence on the need to throw millions of people out of work to restore price stability has been discredited. Although the United States is on track to achieve a soft landing once thought improbable, don’t give Fed Chair Jerome Powell credit; disinflation without mass joblessness is happening despite his move to jack up interest rates, not because of it. And while the Fed is expected to begin lowering interest rates later this year, Powell should still be regarded as a hazard to the health of our polity and our planet.

Just a few weeks ago, Powell told security to “close the fucking door” on a group of climate campaigners who interrupted a speech he was giving. Powell’s palpable contempt for the protesters was another reminder that President Joe Biden should never have renominated the former private equity executive to lead the Fed. The magnitude of Biden’s mistake has become increasingly clear in the roughly two years since he made it.

Put bluntly, Powell is doing a bang-up job of hastening the end of civilized life on Earth. First, his refusal to use the U.S. central bank’s regulatory authority to rein in the financing of fossil fuels is locking in more destructive warming. Second, his prolonged campaign of interest rate hikes is hindering the greening of the economy at a pivotal moment when there is no time to waste. Last but not least, the high interest rate environment Powell has created is improving Donald Trump’s 2024 electoral prospects—and given Trump’s coziness with the fossil fuel industry, his election would be a death knell for the climate.

Nevertheless, we have yet to hear a mea culpa from prominent Powell cheerleaders, who argued that the Fed Chair’s pre-2022 dovishness outweighed his regulatory deficiencies. What has become painfully clear is that Powell’s actual hawkishness is undermining the investment incentives of Biden’s green economic agenda.

Biden tapped Powell for a second four-year term despite opposition from public interest groups, including Public Citizen and the Revolving Door Project, where my colleague Max Moran identified several better candidates. The recent anniversary of Powell’s renomination should invite critical reflection on the arguments made by his supporters and detractors alike during the drawn-out battle to staff Biden’s Fed. Struggles to reshape financial regulation will only grow more fierce in the coming years, and the left needs to be prepared to fight for central bank leaders who are committed to advancing whole-of-government responses to the intertwined climate and inequality crises.

What were people thinking? Reassessing the cases for and against Powell

As evidence mounts that rate hikes imposed by Powell (and many of his central banking peers abroad) are making global climate apartheid more likely, it’s worth revisiting why many establishment liberals and even some progressives advocated on his behalf in the summer and fall of 2021—and why others on the left sounded the alarm.

According to Powell’s defenders at the time, the Fed Chair’s response to the Covid crisis demonstrated that he would strive, unlike his predecessors, to fulfill both parts of the institution’s dual mandate: maintaining low inflation and pursuing full employment. Furthermore, they insisted, Powell’s GOP affiliation would allow him to do so while retaining the support of congressional Republicans, the corporate media, and Wall Street.

Powell’s opponents welcomed the chair’s dovish approach to monetary policy from 2018 to 2021, though they simultaneously acknowledged his history of changing positions based on political whims. They remained unconvinced, however, that Powell was the only candidate who would give maximizing employment equal priority as keeping inflation below the Fed’s arbitrary and untenable 2 percent target. Lael Brainard, then the only Democratic member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, could be expected to do that and perform better at other, equally important aspects of the job, they argued, regardless of whether right-wing lawmakers backed her.

Obviously, the notion that Powell’s purported commitment to full employment would lead the Fed to keep interest rates low was quickly brought into disrepute. Just one week after Biden renominated him, the Fed chair had already changed his tune. And in early 2022, Powell launched the most drastic and sustained campaign of rate hikes in decades, earning comparisons to Paul Volcker.

But Powell’s critics, especially those concerned with climate justice, didn’t need the benefit of hindsight to see that the incumbent was a problematic pick. They had already argued convincingly that Powell’s weaknesses on financial regulation should be disqualifying. The passage of time has revealed how wrong Powell’s supporters were to dismiss progressives’ warnings about Powell’s ethical failures as well as his penchant for deregulation, which reared its ugly head with the 2023 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

Robinson Meyer, the founder of climate media outlet Heatmap and contributor to the New York Times, was an early Powell supporter. His piece, titled “The Planet Needs Jerome Powell,” is an emblematic pro-Powell article published by The Atlantic in September 2021, amid the lengthy fight over Biden’s pick for Fed chair. Meyer admonished the climate left for its supposed lack of seriousness about the Fed’s role in macroeconomic management. According to Meyer’s narrow interpretation (shared by neoliberal blogger Matt Yglesias), the Federal Reserve as an institution is basically reducible to monetary policy and has little of consequence to do with financial regulation.

The demand from “regulation hawks” for a central bank leader who would ramp up Wall Street oversight was misguided, Meyer suggested, because the Fed’s actions on this front “won’t directly reduce carbon pollution.” “Employment hawks,” on the other hand, were right to focus on Powell’s dovishness, he added, because keeping interest rates low to spur green investment is the best a central banker can do on climate. It’s a sad irony that the Fed’s ensuing imposition of rate hikes has undermined the decarbonization effort that Meyer said Powell was best suited to oversee (more on that later).

Contra Meyer, financial regulation is a key aspect of the Fed’s work. If the central bank were to earnestly address the climate emergency’s threats to the financial system (and financiers’ threats to the climate), it would lead banks and other lenders to cease new investment in fossil fuels, an increasingly risky asset class that is not only highly destructive but also likely to become stranded. The continued financing of greenhouse gas emissions makes predatory subprime lending look tame by comparison.

Powell has refused to curb lending to planet-wrecking fossil fuels

Future historians will be at pains to explain why the world’s 60 largest private banks provided more than $5.5 trillion in financing to the fossil fuel industry from 2016 to 2022, including over $1.5 trillion after 2021—the year the International Energy Agency declared that investments in new coal, oil, and gas production are incompatible with its net-zero by 2050 pathway.