Amazon Prime Day and Black Friday have become de facto national holidays of impulsive shopping, ostensibly offering a bevy of “great deals” to tempt consumers. A flood of media articles accompany this celebration of capitalism that masquerades as an event worthy of news coverage. Legions of outlets receive compensation from Amazon in exchange for driving traffic to its platform, often by offering “advice” on the best bargains to snag (e.g. CNN Underscored).

But, as some have already noticed, those advertised promotional discounts can be a mirage and often offer higher price than those regularly found throughout the year. Rather shockingly, even an article on the Washington Post, which Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns, acknowledged this, with the author explaining that “I would have saved, on average, almost nothing during Amazon’s recent fall “Prime Big Deal Days”—and for some big-ticket purchases, I would have actually paid more.” Even so, Prime Day 2025 was Amazon’s biggest ever, with record sales and volume.

In the past few months, I took a deep dive into algorithmic pricing, the machine learning methods used, as well as various case studies, including how repricers work in conjunction with Amazon’s Buy Box to raise prices. Repricing algorithms on Amazon and their interaction with Buy Box rotation indicates that focusing exclusively on common pricing algorithms misses the risk of industry-wide algorithmic standardization. Even though sellers on Amazon can use various repricing providers and even though they may not share competitively sensitive information, the outcomes on Amazon still reflect supra-competitive prices, similar to those achieved from explicit coordination.

Price discrimination is just the tip of the iceberg

Recently, an investigation by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) found that school districts paid widely varying prices for the same products often on the same day, a practice known as price discrimination. While the report focused on schools specifically, businesses that purchase on Amazon should pay attention as well. Segmenting business purchases from those made by consumers is an example of third-order price discrimination.

Employees making purchases for their employer may be less price-sensitive than when making purchases for themselves, allowing Amazon to charge higher prices to the former. Those higher prices eventually get passed on to those businesses’ own consumers, adding to inflationary pressure. Those advocating for lower interest rates would do well to concern themselves with such pricing practices.

The ILSR report attributed the pricing variance it found to Amazon’s opaque dynamic pricing algorithm, the details of which I want to address here. Millions of sellers market their products on Amazon so, of course, one might think that the pricing discipline they (should) exert on each other would result in competitive prices for consumers. After all, as the Lending Tree commercial reminds us, “when banks compete, you win”. So, why aren’t consumers really winning? Why are prices going up?

In my new paper, I discuss the role of algorithms in pricing as well as the various machine learning tools used to implement them in various industries, including E-commerce, hospitality, airlines, real estate, and others. I also talk specifically about pricing on Amazon, which involves the relationship between rules-based and machine learning algorithms.

How repricers’ algorithms interact with Amazon’s Buy Box

On this topic, there’s another factor at play that has flown comparatively under the proverbial radar: the role of Amazon repricers’ respective algorithms and how their interaction with Amazon’s “Buy Box” algorithm enables successful price hikes. Repricing refers to the process of dynamically changing the offer price according to various guidelines. Many companies such as Repricer.com, BQool, Seller Snap, Flashpricer, and Amazon’s own Automate Pricing repricer offer this service.

The Buy Box, now called the “Featured Offer” on Amazon, refers to the box that appears on the right of an Amazon page prominently, displaying the price and shipping details for the seller who currently holds the Buy Box for this product. To see other competing options, a consumer needs to click on “Other Sellers on Amazon,” which appear on a pop-up page.

Not every seller is eligible for the Buy Box—Amazon imposes various eligibility criteria, including prioritizing its own delivery service, Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) over Fulfillment by Merchant (FBM), conduct that prompted an investigation by the European Commission.

Needless to say, the vast majority of purchases, around 80 percent, occur though the Buy Box, which is why sellers want to secure it. Eligibility criteria also matter, because eligible sellers can choose not to compete at all with sellers of the same product, such as those that do not qualify for the Buy Box. So, that seemingly vast landscape of competitors just got smaller. And note that we’re talking about two different types of algorithms that work in concert: Amazon’s algorithm to determine the Buy Box winner and the repricing algorithms that sellers use to set prices.

Repricing on Amazon offers a particularly interesting case study of algorithmic pricing because (1) sellers can use different repricers, (2) repricers can use different algorithms, AI-based (i.e., machine learning), simple rules-based algorithms (e.g., if-then-else statements), or a combination of both, and (3) though sellers can obtain their own data and limited competitor information using the Amazon SP-API, (e.g., though the getcompetitivesummary call), no obvious sharing of competitively sensitive information occurs. In other words, the conditions that have garnered the most focus in algorithmic pricing cases such as the RealPage litigation and Gibson v. Cendyn, do not seem to apply here (at least with repricing).

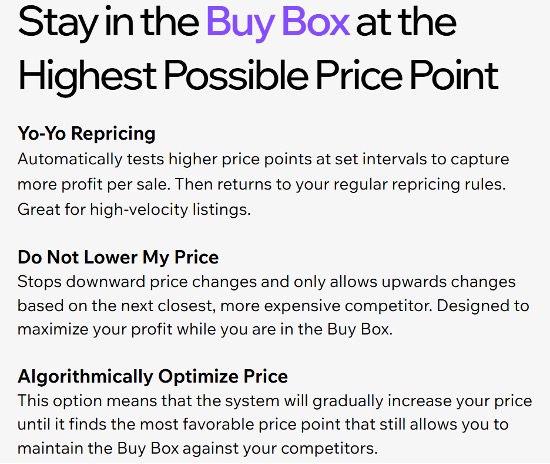

And yet, these repricers openly advertise that their products seek to “avoid price wars” and “look to raise prices 24/7” after their client seller acquires the Buy Box, which one would expect they could only obtain if they were the lowest price offer and would immediately lose upon raising the price.

Not quite. As BQool advertises, its algorithm (in the third bin pictured below) “matches the Buy Box price then increases the price to capture greater profits.”

Hold on, you say. If you raise the price after you get the Buy Box, would you not lose it immediately to a lower priced seller? After all, that’s how competitive markets work—a given seller is a price taker not a price setter, and any attempt to raise the price would result in losing sales to rivals.

Not in this case. Repricers can adopt similar strategies (e.g., “avoid price wars” and “raise prices at every opportunity,” including setting similar floor prices, ignoring each other’s pricing, slowing reaction time (a time delay), and “match but do not undercut.” In other words, repricing algorithms can tacitly collude without any explicit coordination by mutually recognizing each other’s strategy, a process known as “cross-platform recognition.” For example, observing that a seller alters its price every 15 minutes would suggest the use of a repricer.

Simply put, the issue isn’t so much that sellers on Amazon use a common pricing algorithm (though many sellers use one or more repricers), but rather that they use repricers that adopt common strategies based on a common knowledge structure, without directly coordinating. This reflects industry-wide algorithmic standardization. If algorithms settle on a common standard, collusive outcomes can occur even if no obvious rim to an alleged “hub-and-spoke” conspiracy exists. A bevy of research, which I review and describe in my paper, has already observed the same collusive outcomes with Q-learning algorithms (a type of algorithm that falls under reinforcement learning).

Focusing solely on common algorithms can create a tunnel vision that misses other conditions in which algorithmic pricing can harm competition and raise prices. Building a modern-day Maginot Line against the use of common algorithms may accomplish little to defend competition if sellers can outflank it through industry-wide algorithmic standardization.

How tacit coordination occurs

But wait, you say, if Seller A holds the Buy Box, wouldn’t Seller B still have some incentive to undercut Seller A’s price to secure the Buy Box for itself? Otherwise, how does the Buy Box change hands?

This is where the coordination that Amazon’s Buy Box rotation algorithm effectuates comes into play. With rotation, Amazon gives the Buy Box to one seller for a period of time, say two hours, then rotates to another similar seller for the next two hours and so on. Rotation allows sellers (even at slightly different prices) to adopt a “wait my turn” strategy and share the Buy Box rather than aggressively competing for it. The seller holding the Buy Box knows when it can profitably raise the price incrementally without being undercut, and the other sellers that use repricing algorithms have little incentive to undercut the price because they will get their turn to sell at the same higher price.

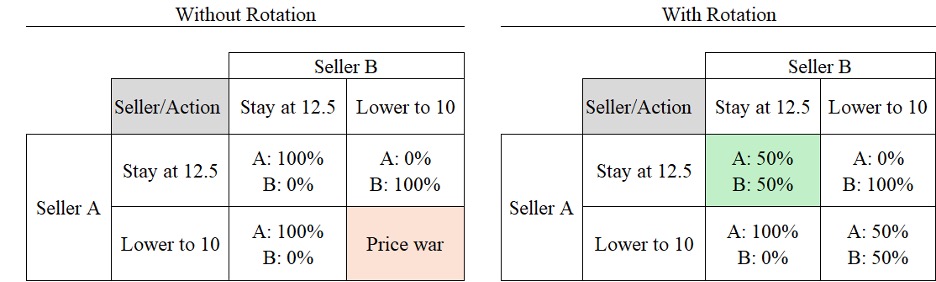

Basic game theory can illustrate the payoff scenarios here. Suppose Seller A has the Buy Box and prices at $12.50. Without rotation, Seller B cannot simply match, it must undercut to get the Buy Box. This will prompt A to respond in turn by undercutting B, resulting in a price war (the bottom right box in the “Without Rotation” scenario). This is the sort of aggressive price competition that would benefit consumers.

With rotation added, however, the incentives change. Seller B knows that by matching A at $12.50, it will eventually get its share of time with the Buy Box. So B doesn’t undercut A, and the price stabilizes at $12.50 (upper left box in the “With Rotation” scenario”). So, both Sellers A and B have the incentive to explore upward, not downward pricing scenarios.

Repricers themselves say as much, advertising that they look to raise prices 24/7. Here’s Flashpricer saying exactly this.

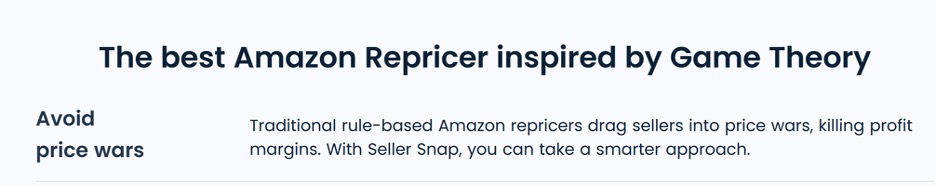

And here’s Sellersnap echoing it.

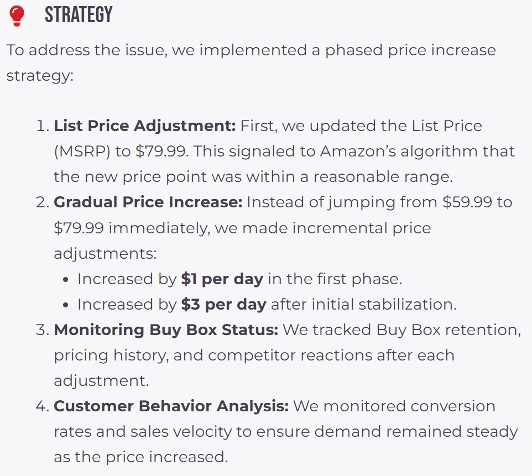

And here’s a case study from marketing agency BellaVix, titled “Successfully raising price while retaining the Buy Box,” that discusses how “A premium skincare brand selling on Amazon faced challenges when attempting to raise the price of their best-selling Crepe Repair Cream from $59.99 to $79.99” (a 33 percent price increase!).

And here’s how BellaVix describe its strategy to overcome those challenges and successfully raise the price to $79.99.

Note that BellaVix first changed the list price, which provides an anchoring effect, not only for consumers but also for Amazon’s algorithm. This move also exploits information asymmetries between the seller and buyers, well discussed in the literature. Such asymmetries result in a market failure, where the price no longer reflects the true market value of the product. Then, BellaVix gradually raised the price, exactly the process that rotation enables and that repricers openly advertise.

In my paper, I discuss the concepts of information asymmetries and anchoring and the latter’s effects on accepting or rejecting price recommendations from algorithms. Perhaps rather shockingly, BellaVix successfully raised the price by 33 percent without losing the Buy Box entirely (though the Buy Box likely rotated), offering a practical example of the strategy I described above.

But, you say, a shopper can just switch to Walmart to avoid the repricers. Sorry, repricers such as Flashpricer, which advertises “AI-powered algorithms for every competition scenario and business model that look for opportunities to raise prices 24/7,” as well as Streetpricer, which “Checks if we still hold the BuyBox after each price increase – backtrack if necessary” are there as well. In fact, repricers are ubiquitous across various platforms, such as Airbnb, Vrbo (e.g., PriceLabs) and others, not just e-commerce.

Bad AI risks driving out the good

Nothing discussed above means that prices always rise. Nor do they need to do so for anticompetitive harm to occur. Remember, the benchmark isn’t whether prices go up or down in the absolute sense, but rather relative to the competitive benchmark. Prices may fall in the absolute sense if, for example, a new entrant unfamiliar with the tacit agreement qualifies for the Buy Box and begins exerting some pricing discipline. Moreover, just because competition occurs in some cases on Amazon does not offset the anticompetitive conduct or render it trivial. After all, not everyone gets lung cancer after smoking, but we still warn against its dangers.

Of course, firms employ algorithms for various beneficial uses, such as identifying fraudulent sellers or counterfeit products. As such, anticompetitive uses of pricing algorithms has another harmful effect—nefarious uses of artificial intelligence can drive out the beneficial ones, an outcome known as Gresham’s Law that occurs through adverse selection.

Much of the problem here results from information asymmetries, both between sellers and buyers and between regulators and algorithmic pricing providers and the platforms on which they occur. Many machine learning algorithms that power AI are “black boxes,” such as neural networks, ensemble models like boosting, random forests, and so on. Having a rudimentary understanding of such algorithms goes a long way toward protecting against anticompetitive consequences they might cause.

Moreover, as this article shows and my paper discusses in some length, harm to competition can occur even using simple rules-based pricing algorithms from independent providers and even in the absence of sharing competitively sensitive information. The old Latin saying caveat emptor (buyer beware) has perhaps never been more poignant than in this dawning age of algorithmic pricing.