As Google faces aggressive scrutiny from the Department of Justice—with the search trial moving to the remedies phase and the ad tech trial moving to closing arguments—there’s an elephant in the room that many antitrust watchers are failing to see: YouTube.

With the platform’s presence on our phones, the part it plays in our online searches, its rapid invasion of our living rooms, and the volume of advertising it serves us, YouTube is an increasingly unavoidable part of our lives. We and other observers have called it “the third leg of the stool that supports Google’s monopoly.” Separating the video giant from the rest of the Google behemoth makes sense as one of the remedies for Google’s decades of monopoly behavior and would reshape the digital landscape for the better—ultimately benefiting consumers, shareholders, and smaller companies in a market newly opened to competition.

Judge Amit Mehta is currently considering what remedies to impose after ruling against Google in August in its landmark search engine antitrust trial. Requiring divestment of one or more business units, like YouTube, is one of his options. A second big antitrust trial, with the government alleging Google illegally controls the advertising technology market, is already underway; and here, too, if the government prevails, divestment would be an option. In the interest of market competition and consumer choice, YouTube—which is intimately bound up with Google’s domination of both sectors—should be among the Google units to be spun off.

Google dominates search with more than 80% of the market, giving it an effective monopoly on the flow of internet information. But YouTube by itself has been recognized as “the world’s second-largest search engine,” handling an estimated 3 billion searches per month. As one commentator noted, after YouTube was founded in 2005, it was “purchased just over a year later by none other than Google, giving it control over the top two search engines on this list.” Another commentator noted recently in the New York Times that, “The gargantuan video site is a lot of things to a lot of people—in different ways, YouTube is a little bit like TikTok, a little like Twitch and a little like Netflix—but I think we underappreciate how often YouTube is a better Google. That is, often YouTube is the best place online to find reliable and substantive knowledge and information on a huge variety of subjects.”

Especially for many younger people, who increasingly prefer video content, YouTube is already the search engine of choice. For these reasons, the European Union recently classified YouTube not only as a large online platform, but a large online search engine. And because YouTube is so tightly integrated with Google Search, it doesn’t represent true competition.

Right now, Google faces little pressure to innovate because it dominates nearly every business it’s in; and when it does innovate, it does so with an eye toward further cementing its complete control of the internet. Google’s recent “innovations” have significantly degraded the Google Search experience, as the company increasingly curtails linking to external sites and instead imposes a “walled garden” strategy that keeps you interacting only with Google’s own content instead of the content you really want. The collateral damage is vast, not only to consumers, but also to content publishers, news organizations, and a variety of other third-party businesses that depend on Google traffic for revenue.

Separating YouTube from the rest of Google would shake up the search, ads, and video markets, and—freed from the market imperatives of a giant corporate parent—could take YouTube development in new directions, with the scale, resources, and user base to challenge Google to compete on features and quality. This would yield more diverse content that better meets user needs, and new opportunities for smaller players to enter the market and innovate.

By owning supply (ad inventory) and setting the terms of demand, Google has been able to charge inflated prices for online advertising while funneling disproportionate revenue to itself and YouTube. Internal communications confirm Google knows their ad fees are roughly double the fair market rate, which one employee admitted is “not long term defensible.” But when you own the entire market, you can charge whatever you want, and Google’s vertical integration has killed competition and put the squeeze on advertisers and publishers. Numerous companies have blamed Google for putting them out of business; new startups that try to break into the business find it tough going.

An independent YouTube would enable the new video company to go head-to-head with Google and negotiate its own deals with advertisers. This would likely lower the fees that Google charged advertisers, increase transparency in how digital ads are bought and sold, create more opportunities for advertisers to effectively reach more target audiences through more platforms, and also open up space for smaller ad tech companies to thrive.

All of this would unlock significant new shareholder value. An independent YouTube’s unique market position and strong brand identity would make it a highly attractive investment, pushing its valuation higher than it is today; analysts have speculated that it could be worth up to $400 billion on its own. Its video-based business model is sufficiently different from Google’s core business of search, so it could attract a different class of investors with different expectations, allowing it to grow more independently and with greater strategic flexibility. And a smaller and more nimble Google would likely provide better returns to its own shareholders.

In short, it’s time to face the elephant in the room, and require Google to spin off YouTube into an independent entity positioned to be a market counterweight. This would be a win-win-win-win: for advertisers, publishers, competitors, and consumers. And it would kick one leg out from under the stool that props up Google’s internet monopoly, which has done too much market damage in too many ways for way too long.

Emily Peterson-Cassin is the Director of Corporate Power at Demand Progress, a national grassroots group with over nearly one million affiliated activists who fight for basic rights and freedoms needed for a modern democracy.

In August, Judge Mehta of the Federal District Court in Washington, D.C., concluded in a careful and detailed opinion that Google had a monopoly in both the internet search market and the associated text advertising market. Google was found to have abused its market power by engaging in exclusionary conduct, including paying large sums of money to equipment makers, browser operators, and cell phone systems to retain this dominance. The opinion declared that while Google got its monopoly because of its “skill, industry, and foresight,” it then used unlawful tactics to entrench and reinforce that position. The decision also recognized the enormous cost of creating and maintaining an effective search engine, as well as a suggestion that the text advertising system involved substantial costs. Given the apparent durability of both these monopolies, the question that the Court now faces is finding an effective remedy.

This week, the Department of Justice (DOJ) is expected to file proposed remedies for this abuse of monopoly power. Several voices have weighed in on remedy design, including The Economist, in a leader titled “Dismantling Google is a terrible idea.” Divestiture of Chrome or Android should be avoided at all costs, argued the magazine, even if that means embracing behavioral remedies such as “limiting its ability to use its search engine to distribute its AI products,” or “mak[ing] public some of the technology that enables its search engine to work, such as its index of web pages and search-query logs.”

In two prior posts, we spelled out two alternative ways to remedy bottleneck monopolies. These monopolies are ones that connect otherwise competitive markets but for a variety of reasons are durable and unavoidable. Obvious examples include electric transmission systems, cell phone service, and natural gas pipelines. The internet world is also subject to a number of bottlenecks.

The Search and Text-Advertising Engines Are Bottleneck Monopolies

Google’s search engine stands between the great mass of users with questions and the entire internet’s resources. Its search engine functions to identify and classify potential responses to the question. The cost of creating the Google search engine was over $20 billion and it requires many billions annually to maintain and expand it. Only two other search engines exist, and one recent effort failed after massive investment. Of the survivors, Microsoft’s Bing has a 10 percent market share overall and the other, Yahoo, has less than 3 percent. Hence, neither is a significant competitor. Browser providers need to have one or more search engines easily accessible for users, and they can’t charge searchers for their searches.

Because the search engine is costly to create and maintain, the question is how to pay for this service. The text-advertising engine is the means for paying for all searches. Text advertisements are the textual lines appearing at the top of any search that implicates a good or service. The line links a searcher to the website of the advertiser that hopes to make a sale.

Google sells such access to advertisers as does Microsoft and Yahoo. Judge Metha found that the creation and maintenance of the text-advertising engine is also very substantial. But at the same time, the other search engines appear to have their own text-advertising engines. This at least suggests that such engines are more readily producible, and that Google’s dominance comes primarily from its control over the search engine. Both browser operators and advertisers agree that they have to use Google’s search engine. They accept the text search engine because that is the means by which Google is compensated. Google also shares that revenue with the browser operators.

The DOJ’s Theory of Harm and Implicit Remedy

The litigation seems to have focused primarily on the anticompetitive effects of the various exclusive dealing contracts that Google obtained to ensure the dominance of its search engine. These contracts involved multi-billion-dollar payments to cell phone makers (like Apple) and browsers (like Mozilla) to ensure Google search was the default option. Nominally, other options could be provided and were included in some browsers, but the effects of Google’s brand recognition and its placement in cell phone and computer browsers resulted in effective retention of a monopoly market share.

While the opinion focuses on the harms resulting from the exclusionary practices of Google, the underlying factual findings suggest that regardless of the specifics of the contracts at this point and for the foreseeable future, the Google search engine will retain its monopoly position. Removing the exclusionary terms from the contracts is unlikely to result in any significant change in the structure of the search engine market.

Perhaps the government belatedly recognized this situation and so tried to shift the focus of its case from an attack on the specific exclusionary effect of the contracts to a broader claim of monopolization. Judge Metha rejected that move because it came late in the litigation. This is somewhat similar to the government’s failure to think through its case against Microsoft in the late 1990s, which started as a challenge to the tying of the operating system to its browser but ultimately morphed into a broader challenge to Microsoft’s monopoly. The failure of the government in that case to have a remedy that would effectively address the monopoly bottleneck of the operating system explains why 25 years later, Window’s still has a monopoly share of computer operating systems and their applications.

The fundamental challenge is to find an effective remedy that will eliminate or significantly reduce the incentive to exploit the bottleneck monopoly and use it to exclude competition in the upstream or downstream markets that the monopoly serves. Eliminating at this point exclusionary contracts given the extraordinary costs of building and operating a search engine that would, at its best, basically duplicate the Google engine, is unlikely to affect the search market in the foreseeable future.

Consider the Alternatives

The central thesis of our prior posts was that where there was an unavoidable bottleneck monopoly, an effective remedy is to change the ownership of that monopoly in a way that would eliminate or greatly attenuate the incentives to exclude and exploit. We also recognized that the first best option would be to break up the monopoly. But in many cases, this is not a feasible option. We suggested that there were two other ways to reallocate ownership and control of the bottleneck. One way is to create a “condominium” that collectively owned the bottleneck, but each user had its own piece to use. The alternative is to move ownership to a “cooperative,” which would both own and operate the bottleneck. While a divestiture remedy is possible, we think that the more likely option is to have either a condo or cooperative own and operate the search engine. As suggested earlier, our assumption here is that the text engine is one that has little exclusionary power on its own and will be further weakened if the current case, in trial, concerning Google’s monopolization of the “ad stack” (e.g., ad server, ad network, and ad exchange) results in dissolution of that monopoly.

Option A: Divestiture

The historic response to monopoly expressly declared in the Standard Oil and American Tobacco cases is to break up the monopoly into separate competing firms. It is hard to imagine how a search engine could be subdivided, but it is possible to imagine that multiple entities could receive the right to use the existing engine, “hiving off” the search engine. Each might then have the right to undertake further development of the search engine. There probably would have to be some significant compensation to Google given its massive investment to date in the search engine. This would limit the number of browser or cell phone operators that could even consider a license.

A second concern would be brand loyalty. Would searchers, assuming that Google was allowed to retain its own version of the search engine, be willing to use alternatives in sufficient quantity that the result would be economically attractive? To recover the costs and make money, text advertising needs to be attractive to advertisers.

Finally, the engine itself needs continued work. This means that those entities that took the engine would need to develop additional capacity to perform those tasks, which is unlikely to be easy or inexpensive. This suggests that divested versions of the Google search engine would struggle to compete in the market.

It would also appear that if the text-advertising engine is currently a bottleneck monopoly in its own right, a licensing system for its use with the further right of each user to amend and improve its version would probably resolve this part of the monopoly. There is no brand loyalty for such engines. Moreover, as noted above, the pending Google ad tech monopoly case is likely to result in a further increase in competition in that area of technology.

Option B: A Condominium Solution

If the search engine is sufficiently distinct from the operation of browser and cell phone operating systems, then one remedy would be to transfer ownership of search engine to an entity owned by the various users, but with the on-going maintenance performed by a separate entity that contracts to provide this service to the owners. This is analogous to a condominium association contracting with a management company. Each owner of a condominium would pay for the managerial services and would be able to use the search engine.

The manager would have significant capacity, however, to exploit this system. If compensation were on a cost-plus basis, that might reduce the risk. An even more open system in which the manager’s task is only to review and implement proposed improvements developed by third parties might reduce further the risk of exploitation. The puzzle then would be how to compensate third parties for developments.

Overall, we are skeptical that a condominium-type structure would be a very effective solution to the monopoly bottleneck that the Google search engine presents.

Option C: Cooperative Solution

A cooperative type of organization would own the search engine itself and share the ongoing costs of its operation, based on usage by the participating enterprise. The cooperative would in turn either have its own staff to maintain the engine or it would contract with various third parties to supply necessary inputs. Each participant would be able to use the search engine as it saw fit and match it with whatever text-advertising system was most attractive given the customer base and technology of that entity.

A cooperative solution to the search engine monopoly is a much more promising solution than the options of injunction, divestiture, or condominium ownership. But we see two real risks and problems. First, there is a question of the incentives to innovate especially where some users would be advantaged over others. The risk is that if most distributors of the search engine are using the same vehicle, they may have a hard time supporting innovations that might favor some types of users, e.g., cell phones, over others, e.g., computers.

Second, as Judge Metha observed, and as The Economist points out, there is a possibility that AI may eventually make search engines obsolete or offer a very credible and open alternative. The judge concluded, however, that this potential was only that. There is no current or immediately foreseeable AI search system. The concern would be that if most search providers are participating in a cooperative that provides a search engine, they may have a collective disincentive to support or sponsor the potentially costly and time-consuming effort to develop an AI search system.

Conclusion

Finding an effective remedy for the monopoly created by Google search and text-advertising engines is a major challenge. Our concern is that the government has too narrowly focused on Google’s exclusionary contracts. Removing those contracts at this late date is unlikely to produce any significant change in the monopolization of these markets and potential for ongoing exploitation and exclusion. It is regrettable that the government did not initiate its case with an explicit focus on a remedy or remedies that could actually affect the future structure and conduct in this market. We have here examined three options that could dissipate the underlying monopoly power. Each has risks and problems, but each is a better alternative than a simplistic elimination of exclusionary contracts.

Professor Tim Wu, former White House advisor on antitrust, offered remedies following Judge Mehta’s decision in the U.S. Google Search case. He identified both Google’s revenue-sharing agreements that exclude competitors and its access to certain “choke points” as a basis for remedies. A divestment order of Chrome and the Android operating system was proposed, as well as an access remedy to Google’s browser, data and A.I. technologies.

It is hard to see how the transfer of a browser monopoly into others’ hands, however, would facilitate access and use of it. That could repeat the mistake of the AT&T 1984 divestiture order that transferred local access monopolies into separate ownership without creating any competitive constraint or pressure on those local business to innovate and compete. In a follow up article, Julia Angwin pointed out the fundamental problem being the Google search results pages, facing no competitive pressure, are now “a pulsing ad cluttered endless scroll,” which masks relevant results. Google’s ad-fuelled profit maximisation leads it to promote that which is remunerative over that which is more relevant.

Also, there remains a major issue with any access order: Will it be able to withstand future technology changes used by Google to circumvent their aims? A crucial issue in writing an order to a monopoly tech company to provide access to XYZ or supply XYZ interface, and the day after the order being written a technical change (or simply version control) making the order technically outdated and pointless.

Any remedy first needs to stop the infringement, prevent its reoccurrence and restore competition. So, the core problem now is to restore competition to the Google search monopoly. This means finding a competing consumer-facing search product that is ad-funded so that “free at the point of use” search can provide competitive pressure on Google’s own free at the point of use product. A possible optionis canvassed below.

The two-sided nature of the search market means any effective solution needs to create consumer-facing competition with Google Search pages and business-facing competition for Google’s Search Text Advertising offering. A starting point for remedies is then prohibiting the mechanisms used by Google that restricted competition from rivals. This means prohibiting the revenue-sharing and default-setting deals with Apple and other technology and telecoms companies that have acted as a moat to protect Google’s Search “castle.” However, restoring effective competition going forward also means enabling the use of data inputs and alternative access points (such as the browser) so competing search ads face competitive price pressure.

The proposal below is inspired by the BT Openreach settlement (and prior BT Consent decree). BT proposed an access remedy, which applied to the local loop. Non-discriminatory access to BT’s local loop (Openreach) business was supplied to third parties on the same terms as it was supplied to downstream parts of BT. The obligation applied to the BT Group of companies and its internal divisions, and corporate structure was subject to non-discrimination both on supply and use. This improved upon the AT&T divestiture remedy, which was in operation in the United States at the time. Avoiding the risk of technology change also means taking account of an often-overlooked Consent Decree, which was agreed among BT/MCI/Concert and the DOJ in 1994. That decree broke new ground as it imposed a non-discriminatory “use” obligation on the recipient of services supplied by the monopoly supplier. A similar obligation on non-discriminatory use of inputs could apply to the use by Google of inputs and would apply overtime irrespective of the technical means of supply.

Scale of Google’s data inputs and sunk investments costs

Google now has unrivalled scale in data acquired from billions of users millions of times per day when they interact with Google’s many products. That data is obtained from its ownership of Chrome, the dominant web browser, providing Google with unrivalled browser history data. It also uses other interoperable code (such as that stored in cookies) to check which websites browsers have visited and has an unparalleled understanding of consumers interests and purchasing behavior. Per Judge Mehta’s Memorandum Opinion in USA v Google (Search), data from billions of search histories provides it with “uniquely strong signals” of intent to purchase data that is combined with all data from all other interactions with all of Google’s many products (see trial exhibit of Google presentation: Google is magical). Its knowledge from all data inputs is combined to provide it with high quality information for advertising. The Memorandum Opinion recognizes that “more users mean more advertisers and more advertisers mean more revenues,” and “more users on a GSE means more queries, which in turn means more ad auctions and more ad revenue.” These positive feedback loops suggest increasing returns to scale and returns to the scope of a range of products offered over the same platform using artificial intelligence as part of its systems. It has built one of the most recognized and valuable brands in the world.

The costs facing any competitor seeking to make an entirely new search engine from scratch are now enormous. This is referenced in evidence as the “Herculean problem.” Reference is made to the many billions of dollars that would be needed by Apple to build a new search engine of its own.

Any restoration of competition will now have to overcome these very considerable advantages and sunk costs, while at the same time competing with Google as the established, and well-knownsupplier of the best search engine in the world. That point about the costs being “sunk” for Google but not new entrants will be returned to below.

The Memorandum Opinion refers to the uniqueness of Google’s Search and the search access choke points many times. Access to these unique facilities must now be on the cards as a remedy.

Third party access to data inputs, match keys and access points to support effective competition in “free at the point of use search results businesses”

Google uses data inputs to identify the user’s “purchasing intent” that inform its ads machine. Data inputs are combined from multiple consumer interactions with others digital content and has enabled Google to charge high prices for its search text ads. Google’s Search engine consists of at least three key components: (1) an index of media owner content cataloged by a web crawler, (2) a “relevance engine” to match consumer input to this catalog, (3) ranking and monetization of the search engine results. At a technical level, the online display advertising system relies on match keys that enable the matching of demand for ad inventory to match a supplier of ad inventory. Third parties need access to these data inputs currently uniquely available to Google, to derive user’s purchasing intent. Competing rivals could then employ the input data and match keys to match inventory supporting display advertising and competing search page results businesses using Google’s relevance engine.Use of such inputs would help drive down prices for ads in competing search businesses.

Access points for search businesses include the Chrome browser. Here, the idea that the browser could be quarantined, as suggested by Professor Wu, could be picked up. The browser would also need to be monitored so that it provides a neutral gateway to the web. It is a choke point that can be enhanced with additional functionality – a wallet in the browser substitutes for decentralized wallets that could otherwise be deployed by competing websites. As was the case with the 1956 AT&T consent decree, AT&T was prevented from competing in areas that were open to competition – so too Google could be prevented from adding functionality to its gateway that could be provided by others elsewhere on the web. The browser then loses its position as gateway controller and becomes a neutral window on the web.

Google is owned by Alphabet so there is an opportunity to apply an obligation to Alphabet not to discriminate in the supply of its relevance engine as between Google and third parties rather than its Search system as a whole. That would enable competition between pages and page presentations offered by different businesses. It would overcome the enormous costs and “Herculean” task of creating a new search engine from scratch. New players might then be tempted to enter that business and resell Alphabet’s relevance engine results combined with its own ads or ads from third parties, which would increase price pressure on search ads.

Currently, 80 percent of the SERP is composed of advertising of one sort or another. Enabling competition in the provision of search results could avoid the morass of current search pages and encourage both quality and price competition. This could benefit both consumers and advertisers.Alternative search businesses could be expected to innovate in the way that they provide and present ads; higher proportions of the results pages could be composed of relevant results and fewer ads. If competing businesses had access to Alphabet’s relevance engine and data inputs they could use them for their own advertising, introducing price pressure on Google’s search text ads. New entrants could be expected to finance their businesses quickly given that they would be reselling a proven search product.

Availability of distribution deals with Google’s revenue sharing partners

The current agreements with Apple, OEMs and telecoms carriers operate as exclusive agreements. They contain contractual restrictions in the form of default settings and revenue sharing payments,which incentivize the parties to promote Google Search Ads. The scale of the payments operates as a disincentive and prevents the parties from offering products competing with Google in search.

Removal of only the contractual default setting is likely to be insufficient to end the anticompetitive effect of the agreements and would go no way to restoring competition. The sharing of revenue from Google’s Search advertising must end if competition between new search advertising players is to be established.

Ending the current distribution deals on a revenue-sharing basis creates a problem of what is an acceptable replacement deal. If Google products are to compete on their merits no restriction at all should be imposed on distributors from providing competing alternatives. However, Google’s distributors will still need to be paid for distribution and the volumes and scale of payments is so large that current recipients are still likely to only sell Google products, even if the restrictive provisions are removed. They are unlikely to take the risk of backing a competitor search product if some form of competition in search is not restored. If access to Alphabet’s relevance engine is mandated as described above that would also help to restore competition at the distributor level.

A proposed access remedy needs to underpin the restoration of competition

A remedy order applicable to Alphabet could provide access to an independent and quarantined browser (access point) and search relevance engine. That would not restore competition alone. Overcoming the considerable barrier to entry of a new entrant seeking to build its own relevance engine and attracting new users while competing with Google is very hard. It is currently prohibitive,even for Apple.

When considering the issue further, it is important to appreciate that:

• The relevance engine and index are currently both organizationally and technically separate from the ads and ad network organization.

• Search is currently optimized by people working in a search business. There are separate groups of people that work on products and separate organizations for advertising.

• Alphabet’s products (news, maps, images, shopping, etc.) are interweaved between relevant search results when the page is presented to end users. An effective remedy could build on these existing organizational and business boundaries.

If third party competitors could access the relevance engine and its index on non-discriminatory terms, they may be able to create effective competition between new “Search Engine Results” businesses. Those businesses would access the substantial sunk investments already made in optimizing search relevant to users’ needs and overcome the substantial “Google” brand value. As noted above, that investment is sunk for Google but represents a considerable barrier to entry for others. Since much of that value has been obtained illegally, there would be a case for stripping Alphabet of that value. Perhaps a better solution here would be to enable the use of the brand to support entry. New competitors would be known to be using Google’s world-renowned relevance engine. The established reputation for quality would help entry. As this is central to restoring competition compensation for use is then a non-issue.

Moreover, Google currently offers access to its relevance engine to companies (like Duck Duck Go) that would resell them, so cannot easily suggest that the above proposal is unworkable.

How the proposal addresses technology changes over time

The law has been broken through the denial of access to data inputs and choke points, and thusdeprived rivals of scale. No other players have sufficient scale to replicate Google’s position. Access to the same data that is used in Google Ads would be a starting point for competitors to create competing search ads from. The solution is access to the IDs and the data inputs that Alphabet uses to fund its search business. Obligations can be crafted to access data feeds for non-discriminatory use of whatever Google uses.

To be clear, there are two critical data feeds that will be needed for competitors to function: (1) Access to the Google relevance engine. This would enable competitors to offer a highly relevant search product. Results would be from a proven and established, world renowned and high-quality source; and (2) Access to the data inputs and advertising IDs and match key data, which are used in Google search ads to identify purchasing intent that can be matched with available advertising inventory.

As a matter of U.S. law and practicality, a non-discrimination obligation on usage can be contained in an order addressed to Google as the user of a search engine or data source owned by Alphabet. As a usage–based non-discrimination obligation applicable to the user of assets owned by the head company, Alphabet, it is materially different from a requirement to supply. There is less of a risk of it offending the case law that defers to businesses deciding whether and with whom they contract – it is instead a requirement not to discriminate between what is received by Google’s search business and what is received by third parties’ search businesses. If Google’s monetization of search results uses no inputs from its relevance engine or data hoard, then it would have no obligation to supply.Conveniently the Alphabet holding company could also be the addressee of the obligation, as was the case with BT Group and its operating corporate entities such as Openreach.

Note that this approach also better addresses the issue of technology change over time. The more usual divestiture order and access obligation suffers from technology being defined at the time the order is written. Since it must be written as a remedy to a defined problem and so if the harm was bundling of interoperability or lack of access to XYZ APIs, then the order mandates unbundling and a requirement to supply XYZ APIs. If a new API is invented that achieves a same end by different means, or a new technology is introduced, there will not have been any case against the defendant for abuse with relation to that new API or technology and no order can easily force the supply of the new API. By contrast, where the addressee of the order is in the same group as the supplier an order can be crafted in terms of non-discrimination in the use of the monopoly asset owned by the group head company and used by a functionally separate business.

Conclusions

This essay addresses the core problem for effective remedies identified in USA v Google (Search). Any remedy needs to address the scale of Google’s data inputs and sunk investments. This is remedied by providing third party access to data inputs and access points to support effective competition in “free at the point of use search results” but would also create competing ads businesses with pressure on ads prices. The current distribution and revenue-sharing partners need to be prohibited. The proposed access remedy enables the creation of competition between rival search engine results businesses, imposing market discipline on the promotion and presentation of search results. The proposal addresses technology changes over time by drawing on lessons learned from divestiture in telecommunication and from ensuing that non-discrimination in usage of key inputs is the focus of the remedy.

Additionally, allowing Alphabet to continue to own its browser (even if quarantined) and provide access to search access points means that capital funding will continue to be in the interests of the Alphabet group. Divestiture would otherwise place monopoly assets in others’ hands with incentives to raise price and degrade quality for all those seeking to use them. Funding of divested assets that are currently cost centres in a vertically integrated business would otherwise also be a major issue to overcome. Here, the proposed non-discrimination remedy bites in a different way – so that technology change is not a problem with this type of remedy.

The approach described here would need to be coupled with transparency obligations such that third parties have visibility of what data inputs the Google Search Co receives so that they can make comparisons. Agreements between different divisions of Alphabet – whether partially in separate ownership or otherwise – can be entered into between different corporate entities within Alphabet to more effectively enable oversight across both a corporate and technical boundary. If done carefully, addressing technology, financial and commercial terms, and the scope for technology change circumventing the remedy can be managed. In effect, it would aim to make the remedy future proof.

On the fourteenth of August in the year 2024, The Sling’s humble scribe came into possession of a facsimile of a transcript meticulously typed up by a certain Court Reporter—by way of an avowed acquaintance of the loyal manicurist of said reporter—in the heart of that certain city renowned for its association with that certain Saint, the inimitable bird-bather and wolf-tamer called Francis of Assisi. This impeccable chain of custody establishes beyond reproach the provenance of the narrative contained within the transcript, which itself proclaims an association with that certain hearing in a Court of Judicature in turn associated with the manifold possibilities of crafting a remedy equitably suited to those various monopolistic machinations pertaining to certain shops bearing applications on assorted devices in possession of a telephonic nature.

In the following rendition, all needless matters have been excised, and all excerpts chosen are unerringly and exactly contemporary. So able was the Court Reporter’s work that, in truth, very little was left to the scribe’s editorial discretion but mere clippery, with a few modest extra touches. Indeed, the task could have been delegated to an electronic golem but for the regrettable necessity of forestalling that certain kind of liability associated with counseling readers to engage in nonstandard culinary practices.

Google’s closing argument went… a little something… like this…

Google’s lead attorney, Glenn Pomerantz (henceforth “Google”): Judges shouldn’t be central planners!

Judge James Donato: I totally agree.

Google: Judges shouldn’t micromanage markets!

Judge: I totally agree.

Google: If you order Google to list other app stores on Play, with some interoperability features, you’re a scary unAmerican Soviet central planner.

Judge: Nope.

Google: Yes, you are!

Judge: Not a Communist. Not even a little bit.

Google: Yes, you are!

Judge: Am decidedly not.

Google: Are decidedly too!

Judge: Anything else you’d like to add?

Google: This order would make you a micromanager of markets.

Judge: I’m not telling anyone which APIs to use. There will be a technical monitor.

Google: Then the technical monitor is an unAmerican micromanager!

Judge: Is not.

Google: Is too!

Judge: Let’s move on.

Google: Yes, my next slide says we must march through the case law. The case law says… drumroll! …that central planning is bad.

Judge: I totally agree! That’s why I’m not doing it.

Google: Yes, you are.

Judge: No, I’m not. My order will be three pages long. Focused on general principles.

Google: But you’ll have to rule on disputes the technical monitor can’t resolve—super detailed technical things, possibly beyond human understanding.

Judge: Still not a Communist.

Google: Well, let’s not forget the *life-changing magic* of Google’s *amazing* origin story. Google was pretty much the maverick heroic Prometheus of the Information Superway.

Judge: I totally agree!

Google: You do?

Judge: Yes. Google had superior innovation. Success is not illegal. What’s illegal is then building a moat through anticompetitive practices.

Google: You want to impose these mean remedies because you hate Google.

Judge: Not at all. And this isn’t about me; I’m charged with the duty to impose a remedy based on a jury verdict. I have to follow through on the jury’s conclusion that Google illegally maintained a monopoly over app stores.

Google: That’s central planning!

Judge: Still not a Communist.

Google: I never said you were a Communist.

Judge: Is “central planning” just your verbal tic then? Like um or uh?

Google: Maybe. I’ll have it checked out.

Judge: Nondiscrimination principles and a ban on anticompetitive contract terms are time-tested, all-American, non-Communist remedies.

Google: You know how some people are super-bummed they were born after all the great bands?

Judge: What, are you saying you miss Jimi Hendrix?

Google: That’s more Apple’s thing. What I think about, late at night, is how tragic it is that Joseph McCarthy died so young.

Judge: Huh, Wikipedia says 48. That *is* kind of young.

Google: Thank you for taking judicial notice of that. By the way, have you ever read Jorge Luis Borges?

Judge: Do I look like someone who reads Borges?

Google: Your Honor, Borges had this story about an empire where “the art of cartography was taken to such a peak of perfection” that its experts “drew a map of the empire equal in format to the empire itself, coinciding with it point by point.”

Judge: Do you have a point?

Google: The map was the same size as the empire itself! Isn’t that amazing? We think remedies need to be just like that. Every part of a remedy needs to be mapped onto an exact twin causal anticompetitive conduct.

Judge: That’s not the legal standard for prying open markets to competition. If I don’t grant Epic’s request, what should I do instead?

Google: Instead of Soviet-style success-whipping, the court should erect a statue to my memory. Or at the very least, overrule the jury.

Judge: That’s up to the appeals court now. We’re here to address remedies. You tell me, what’s an appropriate remedy for illegal maintenance of monopoly?

Google: Nothing.

Judge: Not an option.

Google: Okay, look, we’re open to reasonable compromise here: how about a remedy that sounds like something… but is actually nothing?

Judge: What would the point of winning an antitrust case be then? Why would anyone put in all that time and money and effort to bring a case?

Google: Exposure.

Judge: Your competitors aren’t millennial influencers hoping to pay rent with “likes.” They need ways to earn actual legal tender through vigorous competition.

Google: Your Honor, respectfully, legal tender is central planning.

Judge: I guarantee you my order will not touch monetary policy with a ten-foot pole.

Google: Very well but as you can see it is important to start from first principles when debating remedies. Before we do anything rash that could ruin smartphones, crash the entire internet, and send the nuclear triad on a one-way trip to Soviet Communist Russia, we need to take a step back and ask ourselves “What even *is* an app store?”

Donato: Hell no we don’t. We’ve been through *four years* of litigation and a full jury trial. This is no time to smoke up and get metaphysical…

Google: Out, out damn central planner!

Judge: Was that outburst medical or intentional?

Google: Both.

Court Reporter: Can we wrap this up? I’m running late for my manicure.

Judge: I’ve heard enough. I’m mostly going to rule against Google. But there was one part of your argument that I *did* find extremely compelling, and I will rule for Google on that point.

Google: Really?

Judge: Yes, and you put it best on your own website, so I’ll let that record speak for itself: https://tinyurl.com/neu4weu2

Ed. note: Six days later, acting upon advice from a Google search snippet, Soviet troops invaded the courtroom, seeking political asylum.

Laurel Kilgour wears multiple hats as a law and policy wrangler—but, and you probably know where this is going—not nearly as many hats as Reid Hoffman’s split personalities. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the author’s employers or clients, past or present. This is not legal advice about any particular legal situation. Void where prohibited.

The Justice Department’s pending antitrust case against Google, in which the search giant is accused of illegally monopolizing the market for online search and related advertising, revealed the nature and extent of a revenue sharing agreement (“RSA”) between Google and Apple. Pursuant to the RSA, Apple gets 36 percent of advertising revenue from Google searches by Apple users—a figure that reached $20 billion in 2022. The RSA has not been investigated in the EU. This essay briefly recaps the EU law on remedies and explains why choice screens, the EU’s preferred approach, are the wrong remedy focused on the wrong problem. Restoring effective competition in search and related advertising requires (1) the dissolution of the RSA, (2) the fostering of suppressed publishers and independent advertisers, and (3) the use of an access remedy for competing search-engine-results providers.

EU Law on Remedies

EU law requires remedies to “bring infringements and their effects to an end.” In Commercial Solvents, the Commission power was held to “include an order to do certain acts or provide certain advantages which have been wrongfully withheld.”

The Commission team that dealt with the Microsoft case noted that a risk with righting a prohibition of the infringement was that “[i]n many cases, especially in network industries, the infringer could continue to reap the benefits of a past violation to the detriment of consumers. This is what remedies are intended to avoid.” An effective remedy puts the competitive position back as it was before the harm occurred, which requires three elements. First, the abusive conduct must be prohibited. Second, the harmful consequences must be eliminated. For example, in Lithuanian Railways, the railway tracks that had been taken away were required to be restored, restoring the pre-conduct competitive position. Third, the remedy must prevent repetition of the same conduct or conduct having an “equivalent effect.” The two main remedies are divestiture and prohibition orders.

The RSA Is Both a Horizontal and a Vertical Arrangement

In the 2017 Google Search (Shopping) case, Google was found to have abused its dominant position in search. In the DOJ’s pending search case, Google is also accused of monopolizing the market for search. In addition to revealing the contours of the RSA, the case revealed a broader coordination between Google and Apple. For example, discovery revealed there are monthly CEO-to-CEO meetings where the “vision is that we work as if we are one company.” Thus, the RSA serves as much more than a “default” setting—it is effectively an agreement not to compete.

Under the RSA, Apple gets a substantial cut of the revenue from searches by Apple users. Apple is paid to promote Google Search, with the payment funded by income generated from the sale of ads to Apple’s wealthy user base. That user base has higher disposable income than Android users, which makes it highly attractive to those advertising and selling products. Ads to Apple users are thought to generate 50 percent of ad spend but account for only 20 percent of all mobile users.

Compared to Apple’s other revenue sources, the scale of the payments made to Apple under the RSA is significant. It generates $20 billion in almost pure profit for Apple, which accounts for 15 to 20 percent of Apple’s net income. A payment this large and under this circumstance creates several incentives for Apple to cement Google’s dominance in search:

- Apple is incentivized to promote Google Search. This encompasses a form of product placement through which Apple is paid to promote and display Google’s search bar prominently on its products as the default. As promotion and display is itself a form of abuse, the treatment provides a discriminatory advantage to Google.

- Apple is incentivized to promote Google’s sales of search ads. To increase its own income, Apple has an incentive to ensure that Google Search ads are more successful than rival online ads in attracting advertisers. Because advertisers’ main concern is their return on their advertising spend, Google’s Search ads need to generate a higher return on advertising investment than rival online publishers.

- Apple is incentivized to introduce ad blockers. This is one of a series of interlocking steps in a staircase of abuses that block any player (other than Google) from using data derived from Apple users. Blocking the use of Apple user data by others increases the value of Google’s Search ads and Apple’s income from Apple’s high-end customers.

- Apple is incentivized to block third-party cookies and the advertising ID. This change was made in its Intelligent Tracking Prevention browser update in 2017 and in its App Tracking Transparency pop-up prompt update in 2020. Each step further limits the data available to competitors and drives ad revenue to Google search ads.

- Apple has a disincentive to build a competing search engine or allow other browsers on its devices to link to competing search engines or the Open Web. This is because the Open Web acts as a channel for advertising in competition with Google.

- Apple has a disincentive to invest in its browser engine (WebKit). This would allow users of the Open Web to see the latest videos and interesting formats for ads on websites. Apple sets the baseline for the web and underinvests in Safari to that end, preventing rival browsers such as Mozilla from installing its full Firefox Browser on Apple devices.

The RSA also gives Google an incentive to support Apple’s dominance in top end or “performance smartphones,” and to limit Android smartphone features, functions and prices in competition with Apple. In its Android Decision, the EU Commission found significant price differences between Google Android and iOS devices, while Google Search is the single largest source of traffic from iPhone users for over a decade.

Indeed, the Department of Justice pleadings in USA v. Apple show how Apple has sought to monopolize the market for performance smartphones via legal restrictions on app stores and by limiting technical interoperability between Apple’s system and others. The complaint lists Apple’s restrictions on messaging apps, smartwatches, and payments systems. However, it overlooks the restrictions on app stores from using Apple users’ data and how it sets the baseline for interoperating with the Open Web.

It is often thought that Apple is a devices business. On the contrary, the size of its RSA with Google means Apple’s business, in part, depends on income from advertising by Google using Apple’s user data. In reality, Apple is a data-harvesting business, and it has delegated the execution to Google’s ads system. Meanwhile, its own ads business is projected to rise to $13.7 billion by 2027. As such, the RSA deserves very close scrutiny in USA v. Apple, as it is an agreement between two companies operating in the same industry.

The Failures of Choice Screens

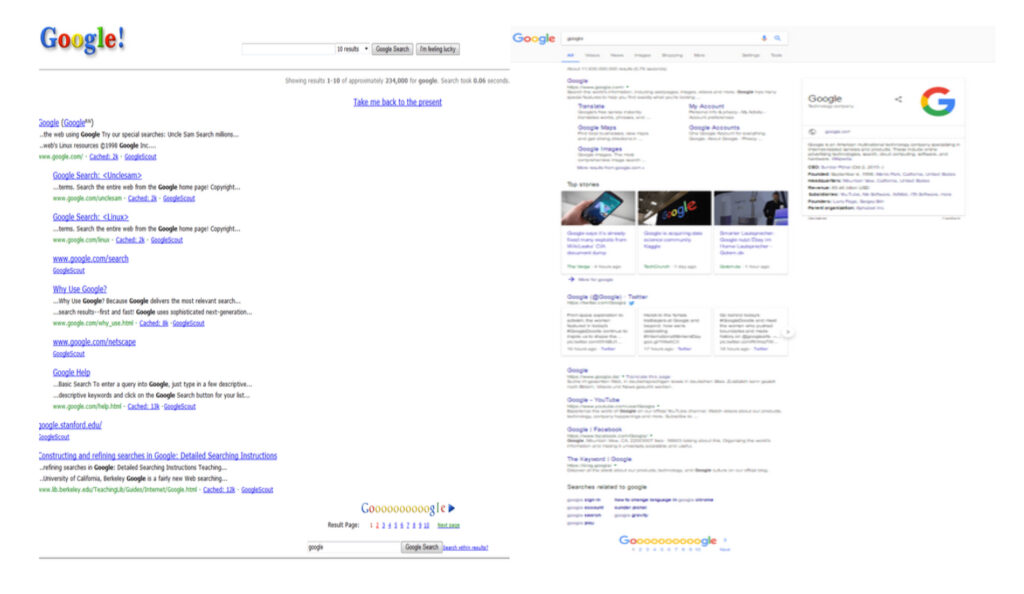

The EU Google (Search) abuse consisted in Google’s “positioning and display” of its own products over those of rivals on the results pages. Google’s underlying system is one that is optimized for promoting results by relevance to user query using a system based on Page Rank. It follows that promoting owned products over more relevant rivals requires work and effort. The Google Search Decision describes this abuse as being carried out by applying a relevance algorithm to determine ranking on the search engine results pages (“SERPs”). However, the algorithm did not apply to Google’s own products. As the figure below shows, Google’s SERP has over time filled up with own products and ads.

To remedy the abuse, the Decision compelled Google to adopt a “Choice Screen.” Yet this isn’t an obvious remedy to the impact on competitors that have been suppressed, out of sight and mind, for many years. The choice screen has a history in EU Commission decisions.

In 2009, the EU Commission identified the abuse Microsoft’s tying of its web browser to its Windows software. Other browsers were not shown to end users as alternatives. The basic lack of visibility of alternatives was the problem facing the end user and a choice screen was superficially attractive as a remedy, but it was not tested for efficacy. As Megan Grey observed in Tech Policy Press, “First, the Microsoft choice screen probably was irrelevant, given that no one noticed it was defunct for 14 months due to a software bug (Feb. 2011 through July 2012).” The Microsoft case is thus a very questionable precedent.

In its Google Android case, the European Commission found Google acted anticompetitively by tying Google Search and Google Chrome to other services and devices and required a choice screen presenting different options for browsers. It too has been shown to be ineffective. A CMA Report (2020) also identified failures in design choices and recognized that display and brand recognition are key factors to test for choice screen effectiveness.

Giving consumers a choice ought to be one of the most effective ways to remedy a reduction of choice. But a choice screen doesn’t provide choice of presentation and display of products in SERPs. Presentations are dependent on user interactions with pages. And Google’s knowledge of your search history, as well as your interactions with its products and pages, means it presents its pages in an attractive format. Google eventually changed the Choice Screen to reflect users top five choices by Member State. However, none of these factors related to the suppression of brands or competition, nor did it rectify the presentation and display’s effects on loss of variety and diversity in supply. Meanwhile, Google’s brand was enhanced from billions of user’s interactions with its products.

Moreover, choice screens have not prevented rival publishers, providers and content creators from being excluded from users’ view by a combination of Apple’s and Google’s actions. This has gone on for decades. Alternative channels for advertising by rival publishers are being squeezed out.

A Better Way Forward

As explained above, Apple helps Google target Apple users with ads and products in return for 36 percent of the ad revenue generated. Prohibiting that RSA would remove the parties’ incentives to reinforce each other’s market positions. Absent its share of Google search ads revenue, Apple may find reasons to build its own search engine or enhance its browser by investing in it in a way that would enable people to shop using the Open Web’s ad funded rivals. Apple may even advertise in competition with Google.

Next, courts should impose (and monitor) a mandatory access regime. Applied here, Google could be required to operate within its monopoly lane and run its relevance engine under public interest duties in “quarantine” on non-discriminatory terms. This proposal has been advanced by former White House advisor Tim Wu:

I guess the phrase I might use is quarantine, is you want to quarantine businesses, I guess, from others. And it’s less of a traditional antitrust kind of remedy, although it, obviously, in the ‘56 consent decree, which was out of an antitrust suit against AT&T, it can be a remedy. And the basic idea of it is, it’s explicitly distributional in its ideas. It wants more players in the ecosystem, in the economy. It’s almost like an ecosystem promoting a device, which is you say, okay, you know, you are the unquestioned master of this particular area of commerce. Maybe we’re talking about Amazon and it’s online shopping and other forms of e-commerce, or Google and search.

If the remedy to search abuse were to provide access to the underlying relevance engine, rivals could present and display products in any order they liked. New SERP businesses could then show relevant results at the top of pages and help consumers find useful information.

Businesses, such as Apple, could get access to Google’s relevance engine and simply provide the most relevant results, unpolluted by Google products. They could alternatively promote their own products and advertise other people’s products differently. End-users would be able to make informed choices based on different SERPs.

In many cases, the restoration of competition in advertising requires increased familiarity with the suppressed brand. Where competing publishers’ brands have been excluded, they must be promoted. Their lack of visibility can be rectified by boosting those harmed into rankings for equivalent periods of time to the duration of their suppression. This is like the remedies used for other forms of publication tort. In successful defamation claims, the offending publisher must publish the full judgment with the same presentation as the offending article and displayed as prominently as the offending article. But the harm here is not to individuals; instead, the harm redounds to alternative publishers and online advertising systems carrying competing ads.

In sum, the proper remedy is one that rectifies the brand damage from suppression and lack of visibility. Remedies need to address this issue and enable publishers to compete with Google as advertising outlets. Identifying a remedy that rectifies the suppression of relevance leads to the conclusion that competition between search-results-page businesses is needed. Competition can only be remedied if access is provided to the Google relevance engine. This is the only way to allow sufficient competitive pressure to reduce ad prices and provide consumer benefits going forward.

The authors are Chair Antitrust practice, Associate, and Paralegal, respectively, of Preiskel & Co LLP. They represent the Movement for an Open Web versus Google and Apple in EU/US and UK cases currently being brought by their respective authorities. They also represent Connexity in its claim against Google for damages and abuse of dominance in Search (Shopping).

As the DOJ’s antitrust case against Google begins, all eyes are focused on whether Google violated antitrust law by, among other things, entering into exclusionary agreements with equipment makers like Apple and Samsung or web browsers like Mozilla. Per the District Court’s Memorandum Opinion, released August 4, “These agreements make Google the default search engine on a range of products in exchange for a share of the advertising revenue generated by searches run on Google.” The DOJ alleges that Google unlawfully monopolizes the search advertising market.

Aside from matters relating to antitrust liability, an equally important question is what remedy, if any, would work to restore competition in search advertising in particular and online advertising generally?

Developments in the UK might shed some light. The UK Treasury commissioned a report to make recommendations on changes to competition law and policy, which aimed to “help unlock the opportunities of the digital economy.” The report found that Big Tech’s monopolizing of data and control over open web interoperability could undermine innovation and economic growth. Big Tech platforms now have all the data in their hands, block interoperability with other sources, and will capture more of it, through their huge customer-facing machines, and so can be expected to dominate the data needed for the AI Period, enabling them to hold back competition and economic growth.

The dominant digital platforms currently provide services to billions of end users. Each of us has either an Apple or Android device in our pocket. These devices operate as part of integrated distribution platforms: anything anyone wants to obtain from the web goes through the device, its browser (often Google’s search engine), and the platform before accessing the Open Web, if not staying on an app on an apps store within the walls of the garden.

Every interaction with every platform product generates data, refreshed billions of times a day from multiple touch points providing insight into buying intent and able to predict people’s behavior and trends.

All this data is used to generate alphanumeric codes that match data contained in databases (aka “Match Keys”), which are used to help computers interoperate and serve relevant ads to match users’ interests. These were for many years used by all from the widely distributed Double Click ID. They were shared across the web and were used as the main source of data by competing publishers and advertisers. After Google bought Double Click and grew big enough to “tip” the market, however, Google withdrew access to its Match Keys for its own benefit.

The interoperability that is a feature of the underlying internet architecture has gradually been eroded. Facebook collected its own data from user’s “Likes” and community groups and also withdrew access for independent publishers to its Match Key data, and recently Apple has restricted access to Match Key data that is useful for ads for all publishers, except Google has a special deal on search and search data. As revealed in U.S. vs Google, Apple is paid over $10 billion a year by Google so that Google can provide its search product to Apple users and gather all their search history data that it can then use for advertising. The data generated by end user interactions with websites is now captured and kept within each Big Tech walled garden.

If the Match Keys were shared with rival publishers for use in their independent supply channel and used by them for their own ad-funded businesses, interoperability would be improved and effective competition could be generated with the tech platforms. Competition probably won’t exist otherwise.

Both Google and Apple currently impose restrictions on access to data and interoperability. Cookie files also contain Match Keys that help maintain computer sessions and “state” so that different computers can talk to each other and help remember previous visits to websites and enable e-commerce. Cookies do not themselves contain personal data and are much less valuable than the Match Keys that were developed by Double Click or ID for advertisers, but they do provide something of a substitute source of data about users’ intent to purchase for independent publishers.

Google and Apple are in the process of blocking access to Match Keys in all forms to prevent competitors from obtaining relevant data about users needs and wants. They also prevent the use of the Open Web and limit the inter-operation of their apps stores with Open Web products, such as progressive web apps.

The UK’s Treasury Report refers to interoperability 8 times and the need for open standards as a remedy 43 times; the Bill refers to interoperability and we are expecting further debate about the issue as the Bill passes through Parliament.

A Brief History of Computing and Communications

The solution to monopolization, or lack of competition, is the generation of competition and more open markets. For that to happen in digital worlds, access to data and interoperability is needed. Each previous period of monopolization involved intervention to open-up computer and communications interfaces via antitrust cases and policy that opened market and liberalized trade. We have learned that the authorities need to police standards for interoperability and open interfaces to ensure the playing field is level and innovation can take place unimpeded.

IBM’s activity involved bundling computers and peripherals and the case was eventually solved by unbundling and unblocking interfaces needed by competitors to interoperate with other systems. Microsoft did the same, blocking third parties from interoperating via blocking access to interfaces with its operating system. Again, it was resolved by opening-up interfaces to promote interoperability and competition between products that could then be available over platforms.

When Tim Berners Lee created the World Wide Web in the early 1990s, it took place nearly ten years after the U.S. courts imposed a break-up of AT&T and after the liberalization of telecommunications data transmission markets in the United States and the European Union. That liberalization was enabled by open interfaces and published standards. To ensure that new entrants could provide services to business customers, a type of data portability was mandated, enabling numbers held in incumbent telecoms’ databases to be transferred for use by new telecoms suppliers. The combination of interconnection and data portability neutralized the barrier to entry created by the network effect arising from the monopoly control over number data.

The opening of telecoms and data markets in the early 1990s ushered in an explosion of innovation. To this day, if computers operate to the Hyper Text Transfer Protocol then they can talk to other computers. In the early 1990s, a level playing field was created for decentralized competition among millions of businesses.

These major waves of digital innovation perhaps all have a common cause. Because computing and communications both have high fixed costs and low variable or incremental costs, and messaging and other systems benefit from network effects, markets may “tip” to a single provider. Competition in computing and communications then depends on interoperability remedies. Open, publicly available interfaces in published standards allow computers and communications systems to interoperate; and open decentralized market structures mean that data can’t easily be monopolized.

It’s All About the Match Keys

The dominant digital platforms currently capture data and prevent interoperability for commercial gain. The market is concentrated with each platform building their own walled gardens and restricting data sharing and communication across. Try cross-posting among different platforms as an example of a current interoperability restriction. Think about why messaging is restricted within each messaging app, rather than being possible across different systems as happens with email. Each platform restricts interoperability preventing third-party businesses from offering their products to users captured in their walled gardens.

For competition to operate in online advertising markets, a similar remedy to data portability in the telecom space is needed. Only, with respect to advertising, the data that needs to be accessed is Match Key data, not telephone numbers.

The history of anticompetitive abuse and remedies is a checkered one. Microsoft was prohibited from discriminating against rivals and had to put up a choice screen in the EU Microsoft case. It didn’t work out well. Google was similarly prohibited by the EU in Google search (Shopping) from (1) discriminating against rivals in its search engine results pages, (2) entering exclusive agreements with handset suppliers that discriminated against rivals, and (3) showing only Google products straight out of the box in the EU Android case. The remedies did not look at the monopolization of data and its use in advertising. Little has changed and competitors claim that the remedies are ineffective.

Many in the advertising publishing and ad tech markets recall that the market worked pretty well before Google acquired Double Click. Google uses multiple data sources as the basis for its Match Keys and an access and interoperability remedy might be more effective, proportionate and less disruptive.

Perhaps if the DOJ’s case examines why Google collects search data from its search engine, its use of search histories, browser histories and data from all interactions with all products for its Match Key for advertising, the court will better appreciate the importance of data for competitors and how to remedy that position for advertising-funded online publishing.

Following Europe’s Lead

The EU position is developing. Under the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), which now supplements EU antitrust law as applied in the Google Search and Android Decisions, it is recognized that people want to be able to provide products and services across different platforms or cross-post or communicate with people connected to each social network or messaging app. In response, the EU has imposed obligations on Big Tech platforms in Articles 5(4) and 6(7) that provide for interoperability and require gatekeepers to allow open access to the web.

Similarly, Section 20.3 (e) of the UK’s Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (DMCC) refers to interoperability and may be the subject of forthcoming debate as the bill passes further through Parliament. Unlike U.S. jurisprudence with its recent fixation on consumer welfare, the objective of the Competition and Markets Authority is imposed by the law. The obligation to “promote competition for the benefit of consumers” is contained in EA 2013 s 25(3). This can be expressly related to intervention opening up access to the source of the current data monopolies: the Match Keys could be shared, meaning all publishers could get access to IDs for advertising (i.e., operating systems generated IDs such as Apple’s IDFA or Google’s Google ID or MAID).

In all jurisdictions it will be important for remedies to stimulate innovation, and to ensure that competition is promoted between all products that can be sold online, rather than between integrated distribution systems. Moreover, data portability needs to apply with reference to use of open and interoperable Match Keys that can be used for advertising, and that way address the data monopolization risk. As with the DMA, the DMCC should contain an obligation for gatekeepers to ensure fair reasonable and nondiscriminatory access, and treat advertisers in a similar way to that through which interoperability and data potability addressed monopoly benefits in previous computer, telecoms, and messaging cases.

Tim Cowen is the Chair of the Antitrust Practice at the London-based law firm of Preiskel & Co LLP.