Warner Bros. Discovery (“Warner Brothers”) announced on Wednesday that it is poised to reject a takeover bid by Paramount, clearing the way for Netflix to acquire Warner Brother’s studio and subscription streaming platform, HBO Max. As shown in the figure below, lifted from The Economist, Netflix and Warner Brothers comprise the first- and fourth-largest streaming platforms based on third quarter 2025 global subscribers.

Hence, a merger between the two streaming platforms will further consolidate the industry, similar to Disney’s majority acquisition of Hulu in 2019. But that clear concentration of economic power didn’t stop The Economist from endorsing the merger.

Seemingly at the behest of Netflix, The Economist devoted one of its lead stories to bolstering the claim that Netflix and HBO Max compete for viewers’ attention with YouTube, which mostly offers long-form (around ten minutes), amateur, ad-supported videos; and with TikTok, which offers short-form (around 35 seconds), amateur, ad-supported videos, in a purportedly immense streaming market. Never mind that Netflix and HBO Max offer studio-produced, paid-subscription streaming services of series and movies that often last over an hour. The technical term for what Netflix and HBO Max offer is subscription video on demand (SVOD). And the technical term for what YouTube and TikTok offer is ad-supported video on demand (AVOD). After reviewing purported evidence of substitution between SVOD and AVOD, the neoliberal magazine concludes that “This new competitive landscape means that trustbusters should not rule Netflix out of the Warner race, as many in Hollywood argue. It may be dominant in streaming, but under the broader market definition it is a smaller actor.”

It’s the smallest set of services, stupid!

The question for the relevant antitrust market seems to elude many in the business press and on Twitter. To bring them quickly up to speed, we offer this brief tutorial: When defining a market, the inquiry turns on the smallest collection of services such a hypothetical monopoly provider of said service could profitably raise prices above competitive levels. This test is referred to as the hypothetical monopolist test (“HMT”). Start with a hypothetical monopoly provider of SVOD services. That’s right—one firm that controls all the streaming services listed in the above figure. Could a single SVOD provider with just those assets raise prices over competitive levels of say $10 per month? If the price increase is deemed unprofitable, then the market must be expanded to include nearby substitutes, with the test repeated. (For those who want a deeper dive, see the 2023 Merger Guidelines Section 4.3.A.)

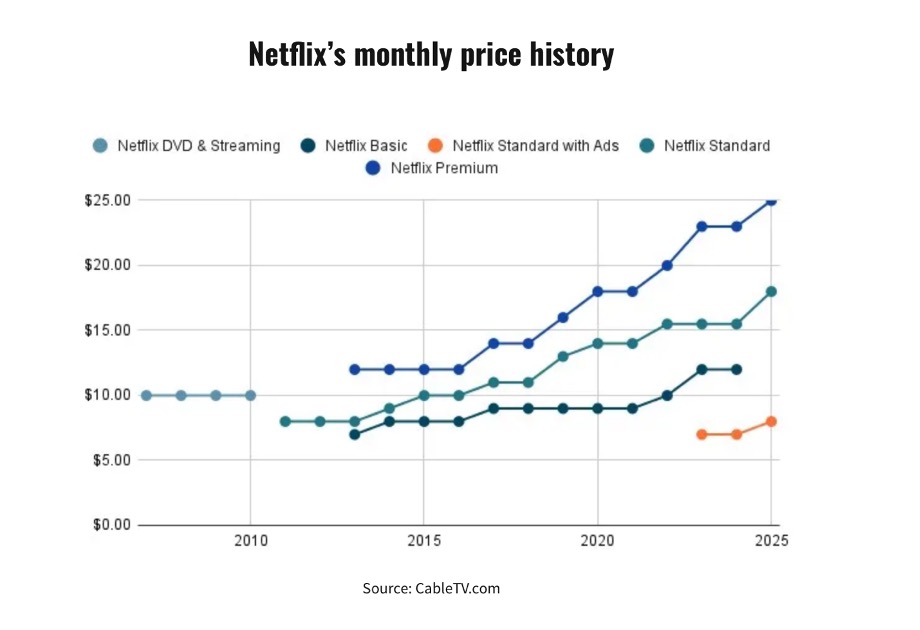

It strains credulity that a hypothetical monopolist of all SVOD services could not raise prices above competitive levels, without also controlling YouTube and TikTok. To where might (say) a Netflix subscriber turn when the price of all of Netflix’s streaming substitutes (HBO, Prime, Apple TV, etc.) also increase? Presumably those paying subscribers would stay put. What The Economist would have you believe is that, when the price of all subscription streaming services increases, a substantial share of those customers would terminate their paid subscriptions and instead spend their time watching free, amateur, short-form and long-form videos. That those outside options are not even priced speaks volumes about the lack of price-discipline imposed by YouTube and TikTok on the SVOD services—that is, the amateur producers of these videos have to give away these services for free (ignoring the ads) as an inducement to watch their content. Indeed, if AVOD services constrained the prices of SVOD services, then why has Netflix been able to raise its subscription for standard and premium service by 29 percent and 39 percent, respectively, since 2020?

Of course, there are other ways to prove a market, such as by invoking the Brown Shoe factors. These are also known as “practical indicia” of a market, such as industry recognition as a separate economic entity, unique production facilities, or distinct prices. See the Merger Guidelines Part 4.3. By any of these standards, SVOD services are a relevant market. CNET, Esquire, Yahoo!Tech, and Consumer Reports maintain rankings of the best subscription streaming services, none of which include YouTube or TikTok. In March of this year, Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos reportedly described YouTube as being for consumers interested in “killing time” rather than “spending time” with professionally produced movies and shows. Compared to YouTube, co-CEO Greg Peters said Netflix is “playing a specific and differentiated role in the ecosystem.” The Intelligencer quotes a top agent saying that traditional streamers like YouTube and HBO Max “do things that YouTube can’t. There’s a good 50 to 60 percent of the audience that literally has never been on YouTube. When you make A Quiet Place, it goes into the Zeitgeist forever, whereas YouTube shows don’t seem to have long-tail resonance.”

With respect to the second factor, production of movies and series for SVOD services take place at professional studios, as opposed to the basement in some amateur’s home. And SVOD services are similarly priced—Netflix’s ad-free service starts at $17.99 per month, while HBO’s ad-free service starts at $22.99 per month—whereas YouTube, TikTok and other AVOD service are generally free.

We note that there is also YouTube Premium, which is essentially identical to YouTube, but with fewer to no ads. While such a service is closer to SVOD in its monetization strategy, it is still not a substitute for Netflix, HBO Max, or other SVOD services considering that YouTube Premium has the same content as ad-supported YouTube. Additionally, there is YouTube TV, which allows for live TV streaming and costs $82.99/month, and which also does not compete with SVOD services (as evinced by content differences between the two service types and by YouTube TV’s significantly higher price point relative to Netflix and HBO Max).

To play up the degree of substitution between SVOD and AVOD services, The Economist notes that “Americans spend longer watching YouTube on tv than on their phones. At the same time Hollywood is relying less on cinemas in favour of tv, and moving to even smaller screens.” That viewers increasingly watch both services on a tv doesn’t imply that the (free) AVOD service disciplines the price of the (paid) SVOD service. The Economist next argues that SVOD platforms are introducing ad-supported offerings, while YouTube is offering no-ad plans, further blurring the lines. So? While the ads can reduce the price of Netflix or HBO Max, the ad-supported price premium is still substantially above the free services of the shorter streamers. And that premium reflects a substantial difference in quality. Finally, The Economist notes some overlap in content across the two products, such as Amazon Prime offering a series starring YouTube’s biggest star (MrBeast), while social platforms are showing television-like content such as YouTube’s “Chicken Shop Date.” This modest overlap hardly constitutes evidence of how consumers of SVOD service would respond to a small increase in the price of their services.

The relevant output market is highly concentrated

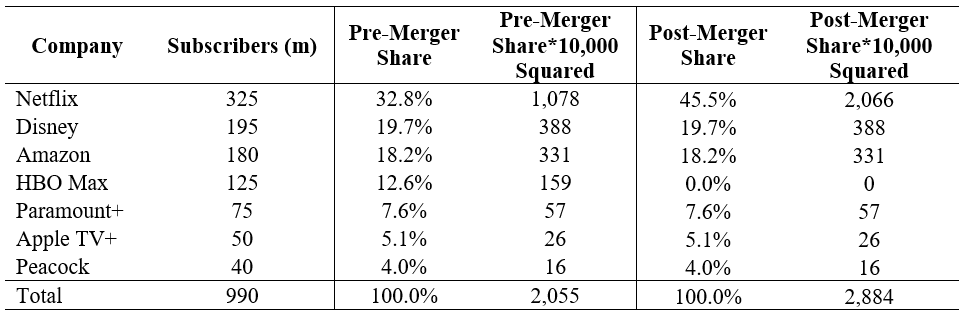

Having defined the relevant output market as SVOD, the next task is to assess the degree of market concentration, both before and after the merger. To compute market shares, we used global streaming subscription data from The Economist (pictured above) for our initial analysis.

Table 1: Concentration Index of the Subscription Streaming Services Market

Source: Subscriber counts are from The Economist.

The pre-merger HHI is 2,055, which the 2023 Merger Guidelines consider “highly concentrated.” The change in HHI owing to the merger is 829 (equal to 2,884 less 2,055). The Guidelines explain that a merger in a highly concentrated market (pre-merger HHI over 1,800) that involves an increase in the HHI of more than 100 points is “presumed to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.”

The Economist cites Ampere Analysis as the source of its subscription data, which we could not access. As a sensitivity check, we also used 2024 U.S.-based subscription data from Statista. The pre-merger HHI falls to 1,778, barely below the 1,800 standard for highly concentrated markets by the Guidelines. The change in HHI is 546 (equal to 2,324 less 1,778). Notably, the combined share of the merging parties using the Statista data is 34 percent. The Guidelines note that “a merger that creates a firm with a share over thirty percent is also presumed to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly if it also involves an increase in HHI of more than 100 points.”

Price effects in the market for subscription streaming services

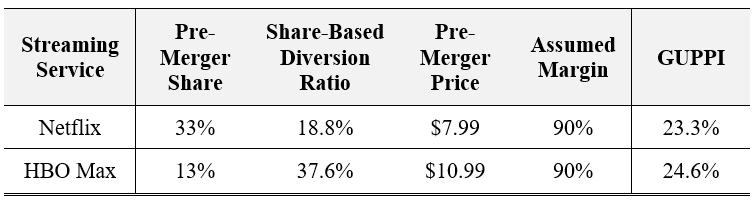

One common method used by economists to estimate the anticipated price effects of a merger is referred to as a “GUPPI” analysis (which stands for “Gross Upward Pricing Pressure Index”). GUPPI analysis follows a simple economic logic—when a firm unilaterally increases price, some of its customers substitute away to its competitors. For instance, if HBO Max were to raise its price, then the law of demand would imply that it would lose some subscribers, with some proportion of these lost subscribers diverted to Netflix. If Netflix were to acquire HBO Max, then these diverted sales from HBO Max to Netflix would remain under the same corporate umbrella, thereby dampening the competitive price discipline that Netflix would have otherwise imposed on HBO Max (and vice-versa).

There are three inputs needed to estimate a GUPPI. First, one needs an estimate of the “diversion ratio” between the merging entities, which measures the proportion of customers a firm would lose to the merging entity if it were to unilaterally increase price. Economists routinely use market shares as a proxy for diversion absent having more detailed, firm-level data. Based on the figure from The Economist above, I estimate that Netflix has a 33 percent market share in streaming, compared to HBO Max’s 13 percent. The share-based diversion ratio from HBO Max to Netflix is therefore 37.6 percent (equal to 0.33 / [1 – 0.13]), and from Netflix to HBO Max is 18.8 percent (equal to 0.13 / [1 – 0.33]).

Second, one needs prices for the merging parties’ products. For our analysis, we use monthly base tier prices for each service. As of December 2025, the price of the Netflix base tier package with ads is $7.99/month, whereas the price of HBO Max’s base tier package with ads is $10.99/month.

Third, one needs an estimate of the merging partner’s economic margin. Economic margin is equivalent to the Lerner Index—it measures the difference between price and marginal cost as a percentage of price. As far as we are aware, the marginal cost for either of streaming service to produce an extra stream is likely close to zero. While these services incur fixed and quasi-fixed costs—most prominently, content costs for either acquiring or producing shows and movies—these costs do not change on a per stream or per user basis. We do not use gross accounting margins, which are sometimes used in place of economic margins, as gross margins are contaminated by the amortization of content costs and other fixed costs over time (which do not reflect true marginal cost in an economic sense). For illustrative purposes, we assume that both platforms’ marginal costs equate to 10 percent of their revenues, which we think is a conservative estimate, thereby implying an economic margin of 90 percent (equal to [1 – 0.1] / 1). More precise information on the merging parties’ economic margins can be obtained via discovery.

The GUPPI for Netflix under a Netflix-HBO Max merger can be calculated as:

where DR_NF->HBO is the diversion ratio from Netflix to HBO Max, M_HBO is the economic margin for HBO Max, and P_HBO / P_NF is the ratio of HBO Max’s base tier monthly price to Netflix’s base tier monthly price.

The table below provides estimates of GUPPIs for both streaming services under the hypothetical merger. It bears noting that GUPPI is a pricing pressure index, but it does not necessarily equate to actual price changes—although the index can often approximate price changes under certain conditions as specified by Miller et al. (2016) and Koh (2025). Generally, antitrust authorities are concerned with GUPPIs greater than 10 percent. For both Netflix and HBO Max, we estimate GUPPIs in excess of 23 percent. These high GUPPIs raise significant alarm as to the potential for this merger to harm consumers, by allowing both platforms to charge higher prices.

Table 2: Gross Upward Pricing Pressure Indices (GUPPIs) Under Netflix-Warner Bros. Discovery Merger

To put into context, in the proposed Penguin Random House-Simon & Schuster merger that was blocked by a judge in 2022, the DOJ’s economist estimated GUPPIs of 3.7 percent to 7.4 percent (note that these GUPPIs correspond to percentage reductions in author compensation as opposed to here, where they represent increases in output market prices). In a 2020 FTC merger case involving consolidation in the hydrogen peroxide industry (FTC v RAG-Stiftung, which involved an output market GUPPI analysis similar to here), the FTC’s economist estimated GUPPIs of 5.5 to 13.2. Any efficiency justifications that Netflix and Warner Bros. Discovery may proffer here are almost certainly outweighed by the magnitude of the upward pricing pressure implied by our estimates.

Not to mention the harms in the labor market

It bears noting that the above results speak only to merger-induced price effects in the output market for streaming subscriptions. They do not address wage effects in the labor (input) market, which tend to be harder to estimate absent detailed, firm-specific data on substitution patterns of talent.

Going back to the book publisher merger, the DOJ’s economist used data on market shares and profit margins to estimate the effect of the merger on author advances using what is referred to as a second-score auction model (for books that acquired an advance of at least $250,000). In this model, the highest-bidder must only bid slightly above the second-highest bidder to win the auction. Such a model finds harm when the two merging parties would otherwise be the first- and second-highest bidders—in such a scenario, the merging party must only pay slightly above what would otherwise have been the third-highest bidder absent the merger. The DOJ’s economist also applied variants of GUPPI tailored towards assessing price effects in an input market (rather than an output market), and towards the market involving auctions. Similar methods could be tailored towards assessing the Netflix-Warner Brothers merger’s effects on streaming market input providers.

There are notable reasons to be as concerned with this merger with respect to its effects on actors, directors, producers, and other input providers in the production of professional long-form streaming movies or series. Netflix and Warner Bros. Discovery both represent major buyers of high-budget films and series in a market with only a handful of meaningful competitors. For directors and producers (and the actors and other input providers they otherwise employ), a greater number of studios implies a greater number of buyers to which input providers can sell their content. Fewer studios available with which to negotiate would mean less competition, driving down compensation for input providers (as was the case in the book publisher merger).

In summary, the proposed Netflix-Warner Brothers mashup is an audacious deal that would be challenged under most administrations. That Netflix is even attempting a horizontal merger in such a concentrated market suggests that its management believes that the Trump administration will not be faithful to merger law or the 2023 Guidelines. As consumers of these services, we can only hope that Netflix has miscalculated.